History of the English Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

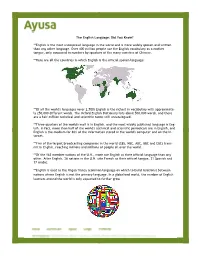

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

The Ideology of American English As Standard English in Taiwan

Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume.7 Number.4 December, 2016 Pp. 80 - 96 The Ideology of American English as Standard English in Taiwan Jackie Chang English Department, National Pingtung University Pingtung City, Taiwan Abstract English language teaching and learning in Taiwan usually refers to American English teaching and learning. Taiwan views American English as Standard English. This is a strictly perceptual and ideological issue, as attested in the language school promotional materials that comprise the research data. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) was employed to analyze data drawn from language school promotional materials. The results indicate that American English as Standard English (AESE) ideology is prevalent in Taiwan. American English is viewed as correct, superior and the proper English language version for Taiwanese people to compete globally. As a result, Taiwanese English language learners regard native English speakers with an American accent as having the greatest prestige and as model teachers deserving emulation. This ideology has resulted in racial and linguistic inequalities in contemporary Taiwanese society. AESE gives Taiwanese learners a restricted knowledge of English and its underlying culture. It is apparent that many Taiwanese people need tore-examine their taken-for-granted beliefs about AESE. Keywords: American English as Standard English (AESE),Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), ideology, inequalities 80 Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Vol.7. No. 4 December 2016 The Ideology of American English as Standard English in Taiwan Chang Introduction It is an undeniable fact that English has become the global lingua franca. However, as far as English teaching and learning are concerned, there is a prevailing belief that the world should be learning not just any English variety but rather what is termed Standard English. -

Reference Guide for the History of English

Reference Guide for the History of English Raymond Hickey English Linguistics Institute for Anglophone Studies University of Duisburg and Essen January 2012 Some tips when using the Reference Guide: 1) To go to a certain section of the guide, press Ctrl-F and enter the name of the section. Alternatively, you can search for an author or the title of a book. 2) Remember that, for reasons of size, the reference guide only includes books. However, there are some subjects for which whole books are not readily available but only articles. In this case, you can come to me for a consultation or of course, you can search yourself. If you are looking for articles on a subject then one way to find some would be to look at a standard book on the (larger) subject area and then consult the bibliography at the back of the book., To find specific contents in a book use the table of contents and also the index at the back which always offers more detailed information. If you are looking for chapters on a subject then an edited volume is the most likely place to find what you need. This is particularly true for the history of English. 3) When you are starting a topic in linguistics the best thing to do is to consult a general introduction (usually obvious from the title) or a collection of essays on the subject, often called a ‘handbook’. There you will find articles on the subareas of the topic in question, e.g. a handbook on varieties of English will contain articles on individual varieties, a handbook on language acquisition will contain information on various aspects of this topic. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Official Standard of the Old English Sheepdog General Appearance: a Strong, Compact, Square, Balanced Dog

Page 1 of 2 Official Standard of the Old English Sheepdog General Appearance: A strong, compact, square, balanced dog. Taking him all around, he is profusely, but not excessively coated, thickset, muscular and able-bodied. These qualities, combined with his agility, fit him for the demanding tasks required of a shepherd's or drover's dog. Therefore, soundness is of the greatest importance. His bark is loud with a distinctive "pot- casse" ring in it. Size, Proportion, Substance: Type, character and balance are of greater importance and are on no account to be sacrificed to size alone. Size - Height (measured from top of withers to the ground), Dogs: 22 inches (55.8 centimeters) and upward. Bitches: 21 inches (53.3 centimeters) and upward. Proportion - Length (measured from point of shoulder to point of ischium (tuberosity) practically the same as the height. Absolutely free from legginess or weaselness. Substance - Well muscled with plenty of bone. Head - A most intelligent expression. Eyes - Brown, blue or one of each. If brown, very dark is preferred. If blue, a pearl, china or wall-eye is considered typical. An amber or yellow eye is most objectionable. Ears - Medium sized and carried flat to the side of the head. Skull - Capacious and rather squarely formed giving plenty of room for brain power. The parts over the eyes (supra-orbital ridges) are well arched. The whole well covered with hair. Stop - Well defined. Jaw - Fairly long, strong, square and truncated. Attention is particularly called to the above properties as a long, narrow head or snipy muzzle is a deformity. -

A COMPARISON ANALYSIS of AMERICAN and BRITISH IDIOMS By

A COMPARISON ANALYSIS OF AMERICAN AND BRITISH IDIOMS By: NANIK FATMAWATI NIM: 206026004290 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT LETTERS AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY “SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH” JAKARTA 2011 ABSTRACT Nanik Fatmawati, A Comparison Analysis of American Idioms and British Idioms. A Thesis: English Letters Department. Adab and Humanities Faculty. Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, 2011 In this paper, the writer uses a qualitative method with a descriptive analysis by comparing and analyzing from the dictionary and short story. The dictionary that would be analyzed by the writer is English and American Idioms by Richard A. Spears and the short story is you were perfectly fine by John Millington Ward. Through this method, the writer tries to find the differences meaning between American idioms and British idioms. The collected data are analyzed by qualitative using the approach of deconstruction theory. English is a language particularly rich in idioms – those modes of expression peculiar to a language (or dialect) which frequently defy logical and grammatical rules. Without idioms English would lose much of its variety and humor both in speech and writing. The results of this thesis explain the difference meaning of American and British Idioms that is found in the dictionary and short story. i ii iii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my original work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Chapter 1. Introduction

1 Chapter 1. Introduction Once an English-speaking population was established in South Africa in the 19 th century, new unique dialects of English began to emerge in the colony, particularly in the Eastern Cape, as a result of dialect levelling and contact with indigenous groups and the L1 Dutch speaking population already present in the country (Lanham 1996). Recognition of South African English as a variety in its own right came only later in the next century. South African English, however, is not a homogenous dialect; there are many different strata present under this designation, which have been recognised and identified in terms of geographic location and social factors such as first language, ethnicity, social class and gender (Hooper 1944a; Lanham 1964, 1966, 1967b, 1978b, 1982, 1990, 1996; Bughwan 1970; Lanham & MacDonald 1979; Barnes 1986; Lass 1987b, 1995; Wood 1987; McCormick 1989; Chick 1991; Mesthrie 1992, 1993a; Branford 1994; Douglas 1994; Buthelezi 1995; Dagut 1995; Van Rooy 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; Gough 1996; Malan 1996; Smit 1996a, 1996b; Görlach 1998c; Van der Walt 2000; Van Rooy & Van Huyssteen 2000; de Klerk & Gough 2002; Van der Walt & Van Rooy 2002; Wissing 2002). English has taken different social roles throughout South Africa’s turbulent history and has presented many faces – as a language of oppression, a language of opportunity, a language of separation or exclusivity, and also as a language of unification. From any chosen theoretical perspective, the presence of English has always been a point of contention in South Africa, a combination of both threat and promise (Mawasha 1984; Alexander 1990, 2000; de Kadt 1993, 1993b; de Klerk & Bosch 1993, 1994; Mesthrie & McCormick 1993; Schmied 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; de Klerk 1996b, 2000; Granville et al. -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

MEL-Cahiers-1 1..36

* omslag Meertens EC 1 09-11-2005 11:45 Pagina 1 MEERTENS ETHNOLOGY CAHIER 1 MEERTENS ETHNOLOGY CAHIER 1 In Towards a Social History of Early Modern Dutch, Peter Burke approaches the history of the Dutch language between 1500 and 1800 from a socio- Towards a cultural historian’s perspective. He investigates the changing relation- ship between the vernacular and Latin; the incorporation (or invasion) of new words from other languages; and the movements towards Social History of standardization and purification, discussing these trends from a comparative, pan-European point of view. Early Modern Dutch Peter Burke (1937) holds a Ph.D. from Oxford University. He is Professor Emeritus of PETER BURKE Cultural History at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge. He is the author of many well-known books, including: The Italian Renaissance (1972), Venice and Amsterdam (1974), Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (1978), The Fabrication of Louis XIV (1992), The Art of Conversation (1993), A Social History of Knowledge (2000), Eyewitnessing (2000), What Is Cultural History? (2004) and Languages and Communities in Early Modern Europe (2004). In all of his works he shows an intelligent capacity to see connections, comparisons and contrasts. He widens the field of cultural history by his practice of building bridges between languages, periods, places, methodologies and 90-5356-861-1 ISBN disciplines, and subsequently investigating what lies beyond; this practice has again been successfully applied in Towards a Social History of Early Modern Dutch. 9 789053 568613 www.aup.nl Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press Towards a Social History of Early Modern Dutch Towards a Social History of Early Modern Dutch Peter Burke The Meertens Ethnology Cahiers are revised texts of the Meertens Ethnology Lectures. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner.