Traditional Shipbuilding Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universitat Pompeu Fabra Estrategias Filipinas Respecto a China

^ ui' °+ «53 T "" Biblioteca Universitat Pompeu Fabra Tesis doctoral Estrategias filipinas respecto a China: Alonso Sánchez y Domingo Salazar en la empresa de China (1581-1593) Barcelona, 1998 Volumen 1 Autor: Manel Ollé Rodríguez Directora: Dolors Folch Fornesa Documento 12 Autor: Alonso Sánchez Lugar y fecha: Manila, 1585 Localización: AGÍ Filipinas 79, ARAH Jesuitas. tomo VII y ANM, Colección Fernández Navarrete, II, fol. 253, dto. 8o.256 2^6 Se reproduce en esta edición el manuscrito localizado en ANM, Colección Fernández Navarrete, II, fol. 253, dto. 8o 238 Relación brebe de la jornada que hizo el P. Alonso Sánchez la segunda vez que fué a la China el año 1584. 257 En el año del582 habiendo yo ido a la China y Macan sobre negocios tocantes a la Gloria de Dios y al servicio de su magestad, por lo que el gobernador D. Gonzalo Ronquillo pretendía y deseaba de reducir aquella ciudad y puerto de portugueses a la obediencia de Su magestad, cuyos eran ya los reynos de Portugal. Pretendían esto el gobernador y obispo y capitanes y las religiones de todas estas yslas, por parecerles que no había otro camino para la entrada de cosa tan dificultosa y deseada como la China, sino era por aquella puerta, principalmente si se hubiese de hacer por vía de guerra, como el gobernador y los seculares pretendían y todos entienden que es el medio por el qual se puede hacer algo con brebedad y efecto. Hízose lo que se deseaba, juntándose con el Capitán Mayor y obispo y electos y las religiones y jurando a su Magestad, por su Rey y Señor natural, de lo qual y de otras cosas importantes dieron al P. -

![Archipel, 100 | 2020 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Novembre 2020, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8932/archipel-100-2020-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-30-novembre-2020-consult%C3%A9-le-21-janvier-2021-398932.webp)

Archipel, 100 | 2020 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Novembre 2020, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021

Archipel Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 100 | 2020 Varia Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/2011 DOI : 10.4000/archipel.2011 ISSN : 2104-3655 Éditeur Association Archipel Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 décembre 2020 ISBN : 978-2-910513-84-9 ISSN : 0044-8613 Référence électronique Archipel, 100 | 2020 [En ligne], mis en ligne le 30 novembre 2020, consulté le 21 janvier 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/2011 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2011 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 janvier 2021. Association Archipel 1 SOMMAIRE In Memoriam Alexander Ogloblin (1939-2020) Victor Pogadaev Archipel a 50 ans La fabrique d’Archipel (1971-1982) Pierre Labrousse An Appreciation of Archipel 1971-2020, from a Distant Fan Anthony Reid Echos de la Recherche Colloque « Martial Arts, Religion and Spirituality (MARS) », 15 et 16 juillet 2020, Institut de Recherches Asiatiques (IRASIA, Université d’Aix-Marseille) Jean-Marc de Grave Archéologie et épigraphie à Sumatra Recent Archaeological Surveys in the Northern Half of Sumatra Daniel Perret , Heddy Surachman et Repelita Wahyu Oetomo Inscriptions of Sumatra, IV: An Epitaph from Pananggahan (Barus, North Sumatra) and a Poem from Lubuk Layang (Pasaman, West Sumatra) Arlo Griffiths La mer dans la littérature javanaise The Sea and Seacoast in Old Javanese Court Poetry: Fishermen, Ports, Ships, and Shipwrecks in the Literary Imagination Jiří Jákl Autour de Bali et du grand Est indonésien Śaivistic Sāṁkhya-Yoga: -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Bangsa Indonesia Sejak

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Bangsa Indonesia sejak dahulu sudah dikenal sebagai bangsa pelaut yang menguasai jalur-jalur perdagangan. Sebagai bangsa pelaut maka pengetahuan kita akan teknologi perkapalan Nusantara pun seharusnya kita ketahui. Catatan-catatan sejarah serta bukti-bukti tentang teknologi perkapalan Nusantara pada masa klasik memang sangatlah minim. Perkapalan Nusantara pada masa klasik, khususnya pada masa kerajaan Hindu-Buddha tidak meninggalkan bukti lukisan-lukisan bentuk kapalnya, berbeda dengan bangsa Eropa seperti Yunani dan Romawi yang bentuk kapal-kapal mereka banyak terdapat didalam lukisan yang menghiasi benda porselen. Penemuan bangkai-bangkai kapal yang berasal dari abad ini pun tidak bisa menggambarkan lebih lanjut bagaimana bentuk aslinya dikarenakan tidak ditemukan secara utuh, hanya sisa-sisanya saja. Sejak kedatangan bangsa Eropa ke Nusantara pada abad ke 16, bukti-bukti mengenai perkapalan yang dibuat dan digunakan di Nusantara mulai terbuka. Catatan-catatan para pelaut Eropa mengenai pertemuan mereka dengan kapal- kapal Nusantara, serta berbagai lukisan-lukisan kota-kota pelabuhan di Nusantara yang juga dibuat oleh orang-orang Eropa. Sejak abad ke-17, di Eropa berkembang seni lukis naturalistis, yang coba mereproduksi keadaan sesuatu obyek dengan senyata mungkin; gambar dan lukisan yang dihasilkannya membahas juga pemandangan-pemandangan kota, benteng, pelabuhan, bahkan pemandangan alam 2 di Asia, di mana di sana-sini terdapat pula gambar perahu-perahu Nusantara.1 Catatan-catatan Eropa ini pun memuat nama-nama dari kapal-kapal Nusantara ini, yang ternyata sebagian masih ada hingga sekarang. Dengan menggunakan cacatan-catatan serta lukisan-lukisan bangsa Eropa, dan membandingkan bentuk kapalnya dengan bukti-bukti kapal yang masih digunakan hingga sekarang, maka kita pun bisa memunculkan kembali bentuk- bentuk kapal Nusantara yang digunakan pada abad-abad 16 hingga 18. -

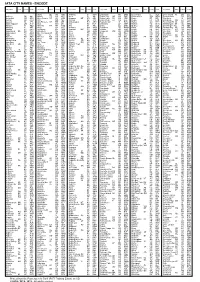

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

Bilge Keel Design for the Traditional Fishing Boats of Indonesia's East Java

International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 11 (2019) 380e395 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/ international-journal-of-naval-architecture-and-ocean-engineering/ Bilge keel design for the traditional fishing boats of Indonesia's East Java * Wendi Liu a, , Yigit Kemal Demirel a, Eko Budi Djatmiko b, Setyo Nugroho b, Tahsin Tezdogan a, Rafet Emek Kurt a, Heri Supomo b, Imam Baihaqi b, Zhiming Yuan a, Atilla Incecik a a Department of Naval Architecture, Ocean and Marine Engineering University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK b Department of Naval Architecture and Shipbuilding, Marine Technology Faculty, Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology, Surabaya, Indonesia article info abstract Article history: Seakeeping, especially for the roll motions, is of critical importance to the safe operation of fishing boats Received 23 February 2018 in Indonesia. In this study, a traditional East Java Fishing Boat (EJFB) has been analysed in terms of its Received in revised form seakeeping performance. Furthermore, a bilge keel was designed to reduce the roll motions of the EJFB 17 July 2018 using multiple stages approach. After installing the designed bilge keels, it was shown that up to 11.78% Accepted 17 July 2018 and 4.87% reduction in the roll response of irregular seaways and the total resistance under the design Available online 9 August 2018 speed, respectively. It was concluded that the roll-stabilized-EJFB will enhance the well-being of the fisherman and contribute to the boats' safe operation, especially in extreme weather conditions. Keywords: East Java Fishing Boat Moreover, the total resistance reduction of the EJFB due to the installation of the designed bilge keels also fi Bilge keel resulted in increased operational ef ciency and reduced fuel costs and fuel emissions for local Roll motion stakeholders. -

Analisis Investasi Perahu Sandeq Bermaterial Kayu Dengan Wilayah

SKRIPSI ANALISIS INVESTASI PERAHU SANDEQ BERMATERIAL KAYU DENGAN WILAYAH OPERASIONAL PANGALI-ALI - PAROMPONG Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Teknik Universitas Hasanuddin Untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Persyaratan Guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Teknik Oleh : ANDI MAHIRA MH D311 16 506 DEPARTEMEN TEKNIK PERKAPALAN FAKULTAS TEKNIK UNIVERSITAS HASANUDDIN GOWA 2021 iii KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji syukur bagi Allah SWT yang senantiasa memberikan jalan yang terbaik bagi umatnya. Allah SWT mengajarkan kepada manusia apa – apa yang tidak diketahuinya. Shalawat dan salam untuk baginda Rasulullah SAW. Atas Berkat Rahmat Allah SWT sehingga walaupun keterbatasan dan kelemahan yang penulis miliki, akhirnya skripsi ini dapat terselesaikan. Pada kesempatan ini penulis ingin menghaturkan terima kasih terutama kepada Kedua Orang Tua Tercinta, terutama Ibunda saya, yang selalu senantiasa berjuang, berusaha mendampingi saya, pengertian terhadap saya dan Saudara- Saudari saya yang berjumlah 13 orang atas segala jerih payah, doa dan dukungannya baik moril maupun materil sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan studi pada Departemen Teknik Perkapalan FT-UH. Ungkapan terima kasih yang amat tinggi juga penulis sampaikan kepada: 1. Ibu Dr. Andi Sitti Chaerunnisa M, ST, MT selaku dosen pembimbing I, terima kasih banyak atas bimbingan dan arahannya selama ini. 2. Ibu Dr. Ir. Hj. Misliah MS.Tr selaku dosen pembimbing II, terima kasih banyak atas bimbingan dan arahannya selama ini. 3. Bapak Ir. Lukman Bochary, MT, selaku penguji, terima kasih atas arahannya. iv 4. Ibu Wihdat Djafar, ST. MT., MlogsupChMgmt , selaku penguji, terima kasih atas arahannya. 5. Bapak Dr. Eng. Suandar Baso, ST., MT, selaku Ketua Departemen Teknik Fakultas Teknik Universitas Hasanuddin atas segala ilmu dan bantuannya. 6. Bapak/Ibu dosen dan staff Departemen Teknik Perkapalan Fakultas Teknik Universitas Hasanuddin atas segala ilmu dan bantuannya. -

Remarks on the Terminology of Boatbuilding and Seamenship in Some Languages of Southern Sulawesi

This article was downloaded by:[University of Leiden] On: 6 January 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 769788091] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Indonesia and the Malay World Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713426698 Remarks on the terminology of boatbuilding and seamanship in some languages of Southern Sulawesi Horst Liebner Online Publication Date: 01 November 1992 To cite this Article: Liebner, Horst (1992) 'Remarks on the terminology of boatbuilding and seamanship in some languages of Southern Sulawesi', Indonesia and the Malay World, 21:59, 18 - 44 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/03062849208729790 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03062849208729790 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Celestial Navigation As a Kind of Local Knowledge of the Makassar Ethnic: an Analysis of Arena Wati’S Selected Works

The 2013 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings Istanbul, Turkey Celestial Navigation as a Kind of Local Knowledge of the Makassar Ethnic: An Analysis of Arena Wati’s Selected Works Sohaimi Abdul Aziz 1 and Sairah Abdullah 2 1School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia 2St. George's Girls' School, Penang, Malaysia. [email protected] Abstract Southeast Asia was known for its seafarers. Indeed, long before the Portuguese arrived in Asian waters, the seafarers had been sailing over the oceans for thousands of miles without a proper compass or written charts. Arena Wati or Muhammad Dahlan bin Abdul Biang is well-known author in Malaysia. He is one of the national laureates of Malay literature. Before he ventured into the world of creative writings, he was a seafarer since the age of 17. He originates from Makassar, an island of seafarers in Indonesia. His vast experiences as a seafarer, who learned and practiced the celestial navigational skills of the Makassar people, have become the important ingredient of his creative writings. Celestial navigation is a navigation of a naturalist that is based on natural elements such as wind direction, wave patterns, ocean currents, cloud formation and so on. Nevertheless, not much research has been doned on his navigational skills as reflected in his works, especially in the contact of local knowledge. As a result, this paper will venture into the celestial navigation and its relationship with the local knowledge. Selected works of Arena Wati, which consists of a memoir and two novels, will be analyzed using textual analysis. The result of this study reveals that the selected works of Arena Wati shows the importance of celestial navigation as part of the local knowledge. -

Bilge Keel Design for the Traditional Fishing Boats of Indonesia's East Java

International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 11 (2019) 380e395 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/ international-journal-of-naval-architecture-and-ocean-engineering/ Bilge keel design for the traditional fishing boats of Indonesia's East Java * Wendi Liu a, , Yigit Kemal Demirel a, Eko Budi Djatmiko b, Setyo Nugroho b, Tahsin Tezdogan a, Rafet Emek Kurt a, Heri Supomo b, Imam Baihaqi b, Zhiming Yuan a, Atilla Incecik a a Department of Naval Architecture, Ocean and Marine Engineering University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK b Department of Naval Architecture and Shipbuilding, Marine Technology Faculty, Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology, Surabaya, Indonesia article info abstract Article history: Seakeeping, especially for the roll motions, is of critical importance to the safe operation of fishing boats Received 23 February 2018 in Indonesia. In this study, a traditional East Java Fishing Boat (EJFB) has been analysed in terms of its Received in revised form seakeeping performance. Furthermore, a bilge keel was designed to reduce the roll motions of the EJFB 17 July 2018 using multiple stages approach. After installing the designed bilge keels, it was shown that up to 11.78% Accepted 17 July 2018 and 4.87% reduction in the roll response of irregular seaways and the total resistance under the design Available online 9 August 2018 speed, respectively. It was concluded that the roll-stabilized-EJFB will enhance the well-being of the fisherman and contribute to the boats' safe operation, especially in extreme weather conditions. Keywords: East Java Fishing Boat Moreover, the total resistance reduction of the EJFB due to the installation of the designed bilge keels also fi Bilge keel resulted in increased operational ef ciency and reduced fuel costs and fuel emissions for local Roll motion stakeholders. -

The Archaeology of Sulawesi Current Research on the Pleistocene to the Historic Period

terra australis 48 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern Volume 28: New Directions in Archaeological Science. New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) A. Fairbairn, S. O’Connor and B. Marwick (2008) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Volume 29: Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. G. Clark, F. Leach Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and and S. O’Connor (2008) Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 30: Archaeological Science Under a Microscope: Studies in Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Residue and Ancient DNA Analysis in Honour of Thomas H. Loy. M. Haslam, G. Robertson, A. Crowther, S. Nugent Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) and L. Kirkwood (2009) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology Volume 31: The Early Prehistory of Fiji. G. Clark and in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter A. -

Multilingual Facilitation

Multilingual Facilitation Honoring the career of Jack Rueter Mika Hämäläinen, Niko Partanen and Khalid Alnajjar (eds.) Multilingual Facilitation This book has been authored for Jack Rueter in honor of his 60th birthday. Mika Hämäläinen, Niko Partanen and Khalid Alnajjar (eds.) All papers accepted to appear in this book have undergone a rigorous peer review to ensure high scientific quality. The call for papers has been open to anyone interested. We have accepted submissions in any language that Jack Rueter speaks. Hämäläinen, M., Partanen N., & Alnajjar K. (eds.) (2021) Multilingual Facilitation. University of Helsinki Library. ISBN (print) 979-871-33-6227-0 (Independently published) ISBN (electronic) 978-951-51-5025-7 (University of Helsinki Library) DOI: https://doi.org/10.31885/9789515150257 The contents of this book have been published under the CC BY 4.0 license1. 1 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Tabula Gratulatoria Jack Rueter has been in an important figure in our academic lives and we would like to congratulate him on his 60th birthday. Mika Hämäläinen, University of Helsinki Niko Partanen, University of Helsinki Khalid Alnajjar, University of Helsinki Alexandra Kellner, Valtioneuvoston kanslia Anssi Yli-Jyrä, University of Helsinki Cornelius Hasselblatt Elena Skribnik, LMU München Eric & Joel Rueter Heidi Jauhiainen, University of Helsinki Helene Sterr Henry Ivan Rueter Irma Reijonen, Kansalliskirjasto Janne Saarikivi, Helsingin yliopisto Jeremy Bradley, University of Vienna Jörg Tiedemann, University of Helsinki Joshua Wilbur, Tartu Ülikool Juha Kuokkala, Helsingin yliopisto Jukka Mettovaara, Oulun yliopisto Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen, Kansalliskirjasto Jussi Ylikoski, University of Oulu Kaisla Kaheinen, Helsingin yliopisto Karina Lukin, University of Helsinki Larry Rueter LI Līvõd institūt Lotta Jalava, Kotimaisten kielten keskus Mans Hulden, University of Colorado Marcus & Jackie James Mari Siiroinen, Helsingin yliopisto Marja Lappalainen, M. -

The Mot Ix Brooklyn

PRICE POUR CEFTTR vol. vi. \v.loorj; NEW-YORK. TIKKSDAY, SEPTEMBER S3, IM80. said Mr. to the reporter. ro con¬ POLITIC* a this cveuinc, Hon," Daggert NEW-YORK STATE Hon to the nerrie'nation f the Vat Ional rt.'lit liv tho r» irmphl."! .e|-rv. arrived mi N w-Bodfesd MOT IX BROOKLYN, ceive the rrsatBsral ans esl ia the Booth¬ ihe itt. THE Etopabii in the PKBS1DKNT1AL CAMPAIGN. randing aratens ; and third. Mal a man shall rate bf -lu whaler George and M era BMtea when wa see this sort of thing vtrtnc ot hw Goa gitan rnrhr, sad asl bi reases third largest ia the Uiitea. (>h, well." ce aeV A LIVKLY ('AHPAIGN Ia' Pattmansnmn ad > «. trula. Mr. Uteh- taidi ac i io\ o» rm police. city nail < i sor\i)s or THE BATTUE, Bataan! of Baltara eea Hui eeo d..i. with peculiar emphasis, '.tba country BAUMM ano ovkkiii'm.im iv rms hy.rna in a r.d thu rrnrart af flwakt IVniiB at f merni Bell rm: comtmol of westers r.v/ojr. thk ssbscxt N'T Rgroarro at pouos bras* Bte Dbsbb> thb IO AT AW ' :iN<; ob the t it died Slates probably wake np Uy-aod-bj aa ta/rbat ntvoiiiAis fBTiaaj io iNiri-wim gEXFKAl GUA VI Xiii IMCI>I1>K HI Saturday ».iet t. io effect th the D t at t \ xmmi.now weald not wah tba Caineae, Lt tina. as .it/.itre ns DBTtX tiif.dk- <t 11 ic party is." (I.i Bs AUK Doing-TUB TAIflFK gCKSTPDR .gossip in W>.IMIHM CHU 11 Mimili, DOC- oompeto ss to tbs pbbmubls < were n nortel io th* will.