Multilingual Facilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Transitivity in Eastern Mansi an Information Structural Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Susanna Virtanen Transitivity in Eastern Mansi An Information Structural Approach Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in Auditorium XII, Main Building, on 14th of March, 2015 at 10 o’clock. 1 © Susanna Virtanen ISBN 978-951-51-0547-9 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-51-0548-6 (PDF) Printed by Painotalo Casper Oy Espoo 2015 2 Abstract This academic dissertation consists of four articles published in peer-reviewed linguistic journals and an introduction. The aim of the study is to provide a description of the formal means of expressing semantic transitivity in the Eastern dialects of the Mansi language, as well as the variation between the different means. Two of the four articles are about the marking of direct objects (DOs) in Eastern Mansi (EM), one outlines the function of noun marking in the DO marking system and one concerns the variation between three-participant constructions. The study is connected to Uralic studies and functional-linguistic typology. Mansi is a Uralic language spoken is Western Siberia. Unfortunately, its Eastern dialects died out some decades ago, but there are still approximately 2700 speakers of Northern Mansi. Because it is no longer possible to access any live data on EM, the study is based on written folkloric materials gathered by Artturi Kannisto about 100 years ago. From the typological point of view, Mansi is an agglutinative language with many inflectional and derivational suffixes. -

An Introduction to Old Persian Prods Oktor Skjærvø

An Introduction to Old Persian Prods Oktor Skjærvø Copyright © 2016 by Prods Oktor Skjærvø Please do not cite in print without the author’s permission. This Introduction may be distributed freely as a service to teachers and students of Old Iranian. In my experience, it can be taught as a one-term full course at 4 hrs/w. My thanks to all of my students and colleagues, who have actively noted typos, inconsistencies of presentation, etc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Select bibliography ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sigla and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... 12 Lesson 1 ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 Old Persian and old Iranian. .................................................................................................................... 13 Script. Origin. .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Script. Writing system. ........................................................................................................................... 14 The syllabary. .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Logograms. ............................................................................................................................................ -

Ling 51: Indo-European Language and Society Germanic Languages I

Ling 51: Indo-European Language and Society Germanic Languages I. Proto-Germanic A. East Germanic 1. Gothic 2. Crimean Gothic B. North Germanic 1. Runic 2. Old Norse and Old Icelandic 3. Old Swedish C. West Germanic 1. Continental a. Old High German b. Old Saxon c. Frankish 2. Ingvaeonic a. Old Frisian b. Old English Numerous dialects. West Saxon is the standard, although modern English descends principally from others Germanic Sound Changes 1. Grimm’s Law Perhaps the most famous of all of the ‘Laws of Indo-European’, Grimm’s Law was established by Jacob Grimm (one of the Grimm brothers), an early 19th century German philologist and collector of German folk materials. PIE Proto-Germanic *p > *f The voiceless stops become *t > * þ the corresponding fricatives *k > *χ (*h) þ = [θ] and χ = [x] *kʷ > *χʷ (*hʷ) *b > *p The voiced stops become *d > *t the corresponding voiceless stops *g > *k *gʷ > *kʷ *bʰ > *β ~ *b The voiced aspirated stops *dʰ > *ð ~ *d become the voiced fricatives, *gʰ > *ɣ ~ g and these usually turn to stops *gʷʰ > *ɣʷ ~ gʷ eventually. Examples of Grimm’s Law *bʰréh₂-ter > *brōþor ‘brother’ *pék ̑u > *feχu ‘wealth on four legs’ *ok ̑tōu̯ > *aχtōu ‘eight’ 2. Verner’s Law Verner’s Law is probably the second most famous IE sound law. After Grimm’s Law was proposed, linguists noticed many cases in which the expected result was not observed for the voiceless fricatives. Sometimes instead of being voiced they emerged as voiceless instead. For some time this was assumed to be because sound changes were not entirely regular, and the idea of reconstructing a proto-language would therefore be impossible. -

Études Finno-Ougriennes, 46 | 2014 the Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish Woman with Deep Blue Eyes 2

Études finno-ougriennes 46 | 2014 Littératures & varia The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes La mère de Dieu khantye et la Finnoise aux yeux bleus Handi Jumalaema ja tema süvameresilmadega soome õde: „Märgitud“ (1980) ja „Jumalaema verisel lumel“ (2002) Elle-Mari Talivee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/efo/3298 DOI: 10.4000/efo.3298 ISSN: 2275-1947 Publisher INALCO Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2014 ISBN: 978-2-343-05394-3 ISSN: 0071-2051 Electronic reference Elle-Mari Talivee, “The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes”, Études finno-ougriennes [Online], 46 | 2014, Online since 09 October 2015, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/efo/3298 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/efo.3298 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Études finno-ougriennes est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 4.0 International. The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes 1 The Khanty Mother of God and the Finnish woman with deep blue eyes La mère de Dieu khantye et la Finnoise aux yeux bleus Handi Jumalaema ja tema süvameresilmadega soome õde: „Märgitud“ (1980) ja „Jumalaema verisel lumel“ (2002) Elle-Mari Talivee 1 In the following article, similarities between two novels, one by an Estonian and the other by a Khanty writer, are discussed while comparing possible resemblances based on the Finno-Ugric way of thinking. Introduction 2 One of the writers is Eremei Aipin, a well-known Khanty writer (born in 1948 in Varyogan near the Agan River), whose works have been translated into several languages. -

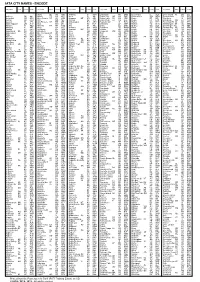

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

UTOPIAN for BEGINNERS an Amateur Linguist Loses Control of the Language He Invented

ANNALS OF LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 24 & 31, 2012 IUE UTOPIAN FOR BEGINNERS An amateur linguist loses control of the language he invented. By Joshua Foer Quijada’s invented language has two seemingly incompatible ambitions: to be maximally precise but also maximally concise. here are so many ways for speakers of English to see the world. We can T glimpse, glance, visualize, view, look, spy, or ogle. Stare, gawk, or gape. Peek, watch, or scrutinize. Each word suggests some subtly different quality: looking implies volition; spying suggests furtiveness; gawking carries an element of social judgment and a sense of surprise. When we try to describe an act of vision, we consider a constellation of available meanings. But if thoughts and words exist on different planes, then expression must always be an act of compromise. Languages are something of a mess. They evolve over centuries through an unplanned, democratic process that leaves them teeming with irregularities, quirks, and words like “knight.” No one who set out to design a form of communication would ever end up with anything like English, Mandarin, or any of the more than six thousand languages spoken today. “Natural languages are adequate, but that doesn’t mean they’re optimal,” John Quijada, a fty-three-year-old former employee of the California State Department of Motor Vehicles, told me. In 2004, he published a monograph on the Internet that was titled “Ithkuil: A Philosophical Design for a Hypothetical Language.” Written like a linguistics textbook, the fourteen-page Web site ran to almost a hundred and sixty thousand words. It documented the grammar, syntax, and lexicon of a language that Quijada had spent three decades inventing in his spare time. -

Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap

RYAN P. SANDELL Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap . What is Gothic? . Linguistic History of Gothic . Linguistic Relationships: Genetic and External . External History of the Goths Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 2 What is Gothic? . Gothic is the oldest attested language (mostly 4th c. CE) of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. It is the only substantially attested East Germanic language. Corpus consists largely of a translation (Greek-to-Gothic) of the biblical New Testament, attributed to the bishop Wulfila. Primary manuscript, the Codex Argenteus, accessible in published form since 1655. Grammatical Typology: broadly similar to other old Germanic languages (Old High German, Old English, Old Norse). External History: extensive contact with the Roman Empire from the 3rd c. CE (Romania, Ukraine); leading role in 4th / 5th c. wars; Gothic kingdoms in Italy, Iberia in 6th-8th c. Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 3 What Gothic is not... Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 4 Linguistic History of Gothic . Earliest substantively attested Germanic language. • Only well-attested East Germanic language. The language is a “snapshot” from the middle of the 4th c. CE. • Biblical translation was produced in the 4th c. CE. • Some shorter and fragmentary texts date to the 5th and 6th c. CE. Gothic was extinct in Western and Central Europe by the 8th c. CE, at latest. In the Ukraine, communities of Gothic speakers may have existed into the 17th or 18th century. • Vita of St. Cyril (9th c.) mentions Gothic as a liturgical language in the Crimea. • Wordlist of “Crimean Gothic” collected in the 16th c. -

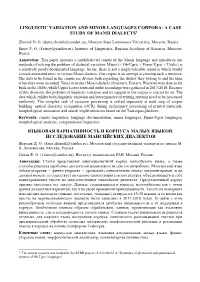

Linguistic Variation and Minor Languages Corpora: a Case Study of Mansi Dialects1

LINGUISTIC VARIATION AND MINOR LANGUAGES CORPORA: A CASE STUDY OF MANSI DIALECTS1 Zhornik D. O. ([email protected]), Moscow State Lomonosov University, Moscow, Russia Sizov F. O. ([email protected]), Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Annotation: This paper presents a multidialectal corpus of the Mansi language and introduces our methods of solving the problem of dialectal variation. Mansi (< Ob-Ugric < Finno-Ugric < Uralic) is a relatively poorly documented language. So far, there is not a single tolerable resource which would contain annotated texts in various Mansi dialects. Our corpus is an attempt at creating such a resource. The data to be found in the corpus are diverse both regarding the dialect they belong to and the time when they were recorded. Texts in extinct Mansi dialects (Southern, Eastern, Western) may date as far back as the 1840s, while Upper Lozva texts and audio recordings were gathered in 2017-2018. Because of this diversity, the problem of linguistic variation and its support in the corpus is crucial for us. The data which exhibit both linguistic variation and heterogeneity of writing systems need to be processed uniformly. The complex task of variation processing is solved separately at each step of corpus building: optical character recognition (OCR) during preliminary processing of printed materials, morphological annotation and search implementation based on the Tsakorpus platform. Keywords: corpus linguistics, language documentation, minor languages, Finno-Ugric languages, morphological analyzer, computational linguistics ЯЗЫКОВАЯ ВАРИАТИВНОСТЬ И КОРПУСА МАЛЫХ ЯЗЫКОВ: ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ МАНСИЙСКИХ ДИАЛЕКТОВ Жорник Д. О. ([email protected]), Московский государственный университет имени М. -

JOURNAL of ETHNOLOGY and FOLKLORISTICS Editor-In-Chief Ergo‑Hart Västrik Guest Editor Pirjo Virtanen, Eleonora A

Volume 11 2017 Number 1 JEFJOURNAL OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORISTICS Editor-in-Chief Ergo-Hart Västrik Guest Editor Pirjo Virtanen, Eleonora A. Lundell, Marja-Liisa Honkasalo Editors Risto Järv, Indrek Jääts, Art Leete, Pille Runnel, Taive Särg, Ülo Valk Language Editor Daniel Edward Allen Managing Editor Helen Kästik Advisory Board Pertti J. Anttonen, Alexandra Arkhipova, Camilla Asplund Ingemark, Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer, Dace Bula, Tatiana Bulgakova, Anne-Victoire Charrin, Carlo A. Cubero, Silke Göttsch, Lauri Harvilahti, Mihály Hoppál, Aivar Jürgenson, Patrick Laviolette, Bo Lönnqvist, Margaret Mackay, Irena Regina Merkienė, Stefano Montes, Kjell Ole Kjærland Olsen, Alexander Panchenko, Éva Pócs, Peter P. Schweitzer, Victor Semenov, Laura Siragusa, Timothy R. Tangherlini, Peeter Torop, Žarka Vujić, Elle Vunder, Sheila Watson, Ulrika Wolf-Knuts Editorial Address Estonian National Museum Muuseumi tee 2 60532 Tartu, Estonia Phone: + 372 735 0405 E-mail: [email protected] Online Distributor De Gruyter Open Homepage http://www.jef.ee http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/jef Design Roosmarii Kurvits Layout Tuuli Kaalep Printing Bookmill, Tartu, Estonia Indexing Anthropological Index Online, DOAJ, ERIH Plus, MLA Directory of Periodicals (EBSCO), MLA International Bibliography (EBSCO), Open Folklore Project This issue is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (projects IUT2-43, IUT22-4 and PUT590) and by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies, CEES). JOURNAL OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORISTICS ISSN 1736-6518 (print) ISSN 2228-0987 (online) The Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics is the joint publication of the Estonian Literary Museum, the Estonian National Museum and the University of Tartu. -

Open-Source Morphology for Endangered Mordvinic Languages

Open-Source Morphology for Endangered Mordvinic Languages Jack Rueter Mika Hämäläinen Niko Partanen Dept. of Digital Humanities Dept. of Digital Humanities Dept. of Finnish, University of Helsinki University of Helsinki Finno-Ugrian [email protected] and Rootroo Ltd and Scandinavian Studies [email protected] University of Helsinki [email protected] Abstract languages. 2002 saw the publication of the first monolingual dictionary of Erzya (Abramov, 2002), This document describes shared development and the manuscript was proclaimed open by the of finite-state description of two closely re- author for future development. The Mordvin lan- lated but endangered minority languages, Erzya and Moksha. It touches upon mor- guages have continued to receive a fair share of pholexical unity and diversity of the two lan- linguistic research interest in the recent years (Luu- guages and how this provides a motivation for tonen, 2014; Hamari and Aasmäe, 2015; Kashkin shared open-source FST development. We de- and Nikiforova, 2015; Grünthal, 2016). scribe how we have designed the transducers After the release first finite-state transducer for so that they can benefit from existing open- the closely related Komi-Zyrian (Rueter, 2000), source infrastructures and are as reusable as possible. it was only obvious that similar work should be done for Erzya Mordvin. Fortunately, over the 1 Introduction past decade there has been an increasing number of publications on Erzya, relating to its morphol- There are over 5000 languages spoken world wide, ogy (Rueter, 2010), its OCR tools (Silfverberg and and a vast majority of them are endangered (see Rueter, 2015) and universal dependencies (Rueter Moseley 2010).