Ling 51: Indo-European Language and Society Germanic Languages I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap

RYAN P. SANDELL Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap . What is Gothic? . Linguistic History of Gothic . Linguistic Relationships: Genetic and External . External History of the Goths Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 2 What is Gothic? . Gothic is the oldest attested language (mostly 4th c. CE) of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. It is the only substantially attested East Germanic language. Corpus consists largely of a translation (Greek-to-Gothic) of the biblical New Testament, attributed to the bishop Wulfila. Primary manuscript, the Codex Argenteus, accessible in published form since 1655. Grammatical Typology: broadly similar to other old Germanic languages (Old High German, Old English, Old Norse). External History: extensive contact with the Roman Empire from the 3rd c. CE (Romania, Ukraine); leading role in 4th / 5th c. wars; Gothic kingdoms in Italy, Iberia in 6th-8th c. Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 3 What Gothic is not... Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 4 Linguistic History of Gothic . Earliest substantively attested Germanic language. • Only well-attested East Germanic language. The language is a “snapshot” from the middle of the 4th c. CE. • Biblical translation was produced in the 4th c. CE. • Some shorter and fragmentary texts date to the 5th and 6th c. CE. Gothic was extinct in Western and Central Europe by the 8th c. CE, at latest. In the Ukraine, communities of Gothic speakers may have existed into the 17th or 18th century. • Vita of St. Cyril (9th c.) mentions Gothic as a liturgical language in the Crimea. • Wordlist of “Crimean Gothic” collected in the 16th c. -

Kashubian INDO-IRANIAN IRANIAN INDO-ARYAN WESTERN

2/27/2018 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4f/IndoEuropeanTree.svg INDO-EUROPEAN ANATOLIAN Luwian Hittite Carian Lydian Lycian Palaic Pisidian HELLENIC INDO-IRANIAN DORIAN Mycenaean AEOLIC INDO-ARYAN Doric Attic ACHAEAN Aegean Northwest Greek Ionic Beotian Vedic Sanskrit Classical Greek Arcado Thessalian Tsakonian Koine Greek Epic Greek Cypriot Sanskrit Prakrit Greek Maharashtri Gandhari Shauraseni Magadhi Niya ITALIC INSULAR INDIC Konkani Paisaci Oriya Assamese BIHARI CELTIC Pali Bengali LATINO-FALISCAN SABELLIC Dhivehi Marathi Halbi Chittagonian Bhojpuri CONTINENTAL Sinhalese CENTRAL INDIC Magahi Faliscan Oscan Vedda Maithili Latin Umbrian Celtiberian WESTERN INDIC HINDUSTANI PAHARI INSULAR Galatian Classical Latin Aequian Gaulish NORTH Bhil DARDIC Hindi Urdu CENTRAL EASTERN Vulgar Latin Marsian GOIDELIC BRYTHONIC Lepontic Domari Ecclesiastical Latin Volscian Noric Dogri Gujarati Kashmiri Haryanvi Dakhini Garhwali Nepali Irish Common Brittonic Lahnda Rajasthani Nuristani Rekhta Kumaoni Palpa Manx Ivernic Potwari Romani Pashayi Scottish Gaelic Pictish Breton Punjabi Shina Cornish Sindhi IRANIAN ROMANCE Cumbric ITALO-WESTERN Welsh EASTERN Avestan WESTERN Sardinian EASTERN ITALO-DALMATIAN Corsican NORTH SOUTH NORTH Logudorese Aromanian Dalmatian Scythian Sogdian Campidanese Istro-Romanian Istriot Bactrian CASPIAN Megleno-Romanian Italian Khotanese Romanian GALLO-IBERIAN Neapolitan Ossetian Khwarezmian Yaghnobi Deilami Sassarese Saka Gilaki IBERIAN Sicilian Sarmatian Old Persian Mazanderani GALLIC SOUTH Shahmirzadi Alanic -

Multilingual Facilitation

Multilingual Facilitation Honoring the career of Jack Rueter Mika Hämäläinen, Niko Partanen and Khalid Alnajjar (eds.) Multilingual Facilitation This book has been authored for Jack Rueter in honor of his 60th birthday. Mika Hämäläinen, Niko Partanen and Khalid Alnajjar (eds.) All papers accepted to appear in this book have undergone a rigorous peer review to ensure high scientific quality. The call for papers has been open to anyone interested. We have accepted submissions in any language that Jack Rueter speaks. Hämäläinen, M., Partanen N., & Alnajjar K. (eds.) (2021) Multilingual Facilitation. University of Helsinki Library. ISBN (print) 979-871-33-6227-0 (Independently published) ISBN (electronic) 978-951-51-5025-7 (University of Helsinki Library) DOI: https://doi.org/10.31885/9789515150257 The contents of this book have been published under the CC BY 4.0 license1. 1 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Tabula Gratulatoria Jack Rueter has been in an important figure in our academic lives and we would like to congratulate him on his 60th birthday. Mika Hämäläinen, University of Helsinki Niko Partanen, University of Helsinki Khalid Alnajjar, University of Helsinki Alexandra Kellner, Valtioneuvoston kanslia Anssi Yli-Jyrä, University of Helsinki Cornelius Hasselblatt Elena Skribnik, LMU München Eric & Joel Rueter Heidi Jauhiainen, University of Helsinki Helene Sterr Henry Ivan Rueter Irma Reijonen, Kansalliskirjasto Janne Saarikivi, Helsingin yliopisto Jeremy Bradley, University of Vienna Jörg Tiedemann, University of Helsinki Joshua Wilbur, Tartu Ülikool Juha Kuokkala, Helsingin yliopisto Jukka Mettovaara, Oulun yliopisto Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen, Kansalliskirjasto Jussi Ylikoski, University of Oulu Kaisla Kaheinen, Helsingin yliopisto Karina Lukin, University of Helsinki Larry Rueter LI Līvõd institūt Lotta Jalava, Kotimaisten kielten keskus Mans Hulden, University of Colorado Marcus & Jackie James Mari Siiroinen, Helsingin yliopisto Marja Lappalainen, M. -

Vocalisations: Evidence from Germanic Gary Taylor-Raebel A

Vocalisations: Evidence from Germanic Gary Taylor-Raebel A thesis submitted for the degree of doctor of philosophy Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex October 2016 Abstract A vocalisation may be described as a historical linguistic change where a sound which is formerly consonantal within a language becomes pronounced as a vowel. Although vocalisations have occurred sporadically in many languages they are particularly prevalent in the history of Germanic languages and have affected sounds from all places of articulation. This study will address two main questions. The first is why vocalisations happen so regularly in Germanic languages in comparison with other language families. The second is what exactly happens in the vocalisation process. For the first question there will be a discussion of the concept of ‘drift’ where related languages undergo similar changes independently and this will therefore describe the features of the earliest Germanic languages which have been the basis for later changes. The second question will include a comprehensive presentation of vocalisations which have occurred in Germanic languages with a description of underlying features in each of the sounds which have vocalised. When considering phonological changes a degree of phonetic information must necessarily be included which may be irrelevant synchronically, but forms the basis of the change diachronically. A phonological representation of vocalisations must therefore address how best to display the phonological information whilst allowing for the inclusion of relevant diachronic phonetic information. Vocalisations involve a small articulatory change, but using a model which describes vowels and consonants with separate terminology would conceal the subtleness of change in a vocalisation. -

Information Transport and Evolutionary Dynamics

Information Transport and Evolutionary Dynamics Marc Harper NIMBioS Workshop April 2015 Thanks to I NIMBioS I John Baez I All the participants Motivation Theodosius Dobzhansky (1973) Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker (1987) The theory of evolution by cumulative natural selection is the only theory we know of that is in principle capable of explaining the existence of organized complexity. Motivation Donald T. Campbell, Evolutionary Epistemology (1974) A blind-variation-and-selective-retention process is fundamental to all inductive achievements, to all genuine increases in knowledge, to all increases in the fit of system to environment. Ronald Fisher, The Design of Experiments (1935) Inductive inference is the only process known to us by which essentially new knowledge comes into the world. Universal Darwinism Richard Dawkins proposed a theory of evolutionary processes called Universal Darwinism( The Selfish Gene, 1976), later developed further by Daniel Dennett (Darwin's Dangerous Idea, 1995) and others. An evolutionary process consists of I Replicating entities that have heritable traits I Variation of the traits and/or entities I Selection of variants favoring those more fit to their environment See also Donald T. Campbell's BVSR: Blind Variation and Selective Retention (1960s) Replication What is replication? The proliferation of some static or dynamic pattern (Lila, Robert Pirsig, 1991). A replicator is something that replicates: I Biological organisms I Cells I Some organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts Hummert et al. Evolutionary game theory: cells as players. Molecular BioSystems (2014) Replication Molecular replicators: I Genes, transposons, bacterial plasmids I Self-replicating RNA strands (Spiegelman's monster) I Viruses, RNA viruses (naked RNA strands) I Prions, self-replicating proteins e.g. -

Ulrich Geupel1, Germanic Workshop Pavia 2015 1St Lesson: Introduction

Ulrich Geupel1, Germanic Workshop Pavia 2015 1st lesson: Introduction and preliminaries 2nd lesson: Important sound changes 3rd lesson: Important basics of morphology 4th lesson: Important basics of syntax and semantics / text readings Lesson 1 The Germanic languages as a branch of the Indo-European (IE) language family Today Germanic languages, mostly English, are spoken in many areas of the world as the main official language (highlighted in dark blue) or at least as one of the official languages (highlighted in light blue). Going back in time exhibits a clearly different picture: The expansion of the Germanic tribes 750 BC – AD 1 (after the Penguin Atlas of World History 1988; which is of course tentative): Settlements before 750 BC New settlements by 500 BC New settlements by 250 BC New settlements by AD 1 Later settlements are: The invasion of Anglo- Saxons to England starting in the 5th century after the retreat of the Romans from the Britannic island; the Norse settlement in Iceland may go back to the 7th or 8th cent. as indicated by archeological findings. The landnámabók (book of invasions), written in the Old Icelandic language, describes increasing populatings from the 9th cent. onwards. In early times ancestors of the Gothic speaking people moved to the east and south as far as to the Crimean peninsula, some words and phrases of their language are preserved in some word lists from the 16th cent. 1 Partly based on didactic material by Sabine Ziegler. So, in the Middle Ages Germanic languages were spoken from Iceland to the Crimea, from Scandinavia to the alps. -

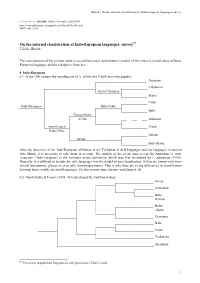

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3. -

The World's Major Languages

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The World’s Major Languages Comrie Bernard Germanic Languages Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203301524.ch2 John A. Hawkins Published online on: 28 Nov 2008 How to cite :- John A. Hawkins. 28 Nov 2008, Germanic Languages from: The World’s Major Languages Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203301524.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 Germanic Languages John A. Hawkins The Germanic languages currently spoken fall into two major groups: North Germanic (or Scandinavian) and West Germanic. The former group comprises: Danish, Norwegian (i.e. both the Dano-Norwegian Bokmål and Nynorsk), Swedish, Icelandic, and Faroese. -

6 X 10.Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-01511-0 - The Germanic Languages Wayne Harbert Index More information INDEX Note: The major Germanic languages (AF, BN, DA, DU, EN, FA, FR, GE, GO, IC, ME, MHG NN, NO, OE, OHG, OS, SW, YI) are cited with such great frequency throughout the book that citing each mention of them in the index is not practicable. Rather, the index only lists the discussions of these languages in the introductory chapter. ablaut 6, 22, 89, 271, 275 assibilation 49 accusative-with-infinitive constructions associative NPs 162–163 261–264 attraction 467–468 adjectives, in adjective phrases 171–175; auxiliary position 288–291 agreement on predicate adjectives 219–221; in comparative constructions 11, Bala 137 174–175; complements of 171–174; Balkan languages 11 position in noun phrase 127–130; weak and Balto-Slavic 11 strong inflection of 6, 130–137 Basque 10, 11 adverbs 370–376; order of 373; sentence Bavarian 48, 146, 218, 366, 456 adverbs and VP adverbs 372–376 Bislama 13 African-American English 273, 475 Bokma˚l20 Afrikaans 17 breaking; in Gothic 55; in Modern Frisian 64; affricates 47–48; and constraints on clusters 71 in Old English 55 Aktionsart see verbal aspect Breton 140 Albanian 11 alliteration in Germanic verse 69 case 103–122; alternatives to 107–111; in anaphors 196–213; short-distance and experiencer constructions 116–122; long-distance 204–211; instrumental 104; lexical and very-long-distance anaphors vs. structural case 112–122, 245; loss of logophors 211–213; with inherently the accusative/ dative distinction -

6 X 10.Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-80825-5 - The Germanic Languages Wayne Harbert Index More information INDEX Note: The major Germanic languages (AF, BN, DA, DU, EN, FA, FR, GE, GO, IC, ME, MHG NN, NO, OE, OHG, OS, SW, YI) are cited with such great frequency throughout the book that citing each mention of them in the index is not practicable. Rather, the index only lists the discussions of these languages in the introductory chapter. ablaut 6, 22, 89, 271, 275 assibilation 49 accusative-with-infinitive constructions associative NPs 162–163 261–264 attraction 467–468 adjectives, in adjective phrases 171–175; auxiliary position 288–291 agreement on predicate adjectives 219–221; in comparative constructions 11, Bala 137 174–175; complements of 171–174; Balkan languages 11 position in noun phrase 127–130; weak and Balto-Slavic 11 strong inflection of 6, 130–137 Basque 10, 11 adverbs 370–376; order of 373; sentence Bavarian 48, 146, 218, 366, 456 adverbs and VP adverbs 372–376 Bislama 13 African-American English 273, 475 Bokma˚l20 Afrikaans 17 breaking; in Gothic 55; in Modern Frisian 64; affricates 47–48; and constraints on clusters 71 in Old English 55 Aktionsart see verbal aspect Breton 140 Albanian 11 alliteration in Germanic verse 69 case 103–122; alternatives to 107–111; in anaphors 196–213; short-distance and experiencer constructions 116–122; long-distance 204–211; instrumental 104; lexical and very-long-distance anaphors vs. structural case 112–122, 245; loss of logophors 211–213; with inherently the accusative/ dative distinction -

Annotated Swadesh Wordlists for the Germanic Group (Indo-European Family)

[Text version of database, created 23/02/2016]. Annotated Swadesh wordlists for the Germanic group (Indo-European family). Languages included: Gothic [grm-got]; Old Norse [grm-ono]; Icelandic [grm-isl]; Faroese [grm-far]; Bokmål Norwegian [grm-bok]; Danish [grm-dan]; Swedish [grm-swe]. DATA SOURCES I. Gothic. Balg 1887 = Balg, G. H. A Comparative Glossary of the Gothic Language, with especial reference to English and German. Mayville, Wisconsin. // A complete dictionary of Gothic, covering the entire text corpus and explicitly listing most of the attestations of individual words; includes extensive etymological notes. Ulfilas 1896 = Ulfilas oder die uns erhaltenen Denkmäler der gotischen Sprache. Paderborn: Druck und Verlag von Ferdinand Schöningh. // A complete edition of Ulfilas' Bible, together with a concicse vocabulary and a brief grammatical sketch of Gothic. Costello 1973 = Costello, John R. The Placement of Crimean Gothic by Means of Abridged Test Lists in Glottochronology. Journal of Indo-European Studies, 1:4, pp. 479-506. // A small paper describing an attempt to apply Swadesh glottochronology to the Crimean variety of Gothic, based on XVIth century data. Includes the complete list of 91 words recorded for Crimean Gothic, 27 of which are on the 110-item list used for the GLD. II. Old Norse. Main source Cleasby & Vigfusson 1874 = Cleasby, Richard. An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Enlarged and completed by Gudbrand Vigfusson, M.A. Oxford: Clarendon Press. // The largest and still the most authoritative dictionary of Old Icelandic, illustrated by numerous 1 examples and richly annotated as far as the semantic and distributional properties of the words are concerned, making it an excellent source for lexicostatistical list construction. -

The Development of a Comprehensive Data Set for Systematic Studies of Machine Translation

The Development of a Comprehensive Data Set for Systematic Studies of Machine Translation J¨orgTiedemann1[0000−0003−3065−7989] University of Helsinki, Department of Digital Humanities P.O. Box 24, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents our on-going efforts to develop a com- prehensive data set and benchmark for machine translation beyond high- resource languages. The current release includes 500GB of compressed parallel data for almost 3,000 language pairs covering over 500 languages and language variants. We present the structure of the data set and demonstrate its use for systematic studies based on baseline experiments with multilingual neural machine translation between Uralic languages and other language groups. Our initial results show the capabilities of training effective multilingual translation models with skewed training data but also stress the shortcomings with low-resource settings and the difficulties to obtain sufficient information through straightforward transfer from related languages. Keywords: machine translation · low-resource languages · multilingual NLP 1 Introduction Massively parallel data sets are valuable resources for various research fields ranging from cross-linguistic research, language typology and translation studies to neural representation learning and cross-lingual transfer of NLP tools and applications. The most obvious application is certainly machine translation (MT) that typically relies on data-driven approaches and heavily draws on aligned parallel corpora as their essential training material. Even though parallel data sets can easily be collected from human transla- tions that naturally appear, their availability is still a huge problem for most languages and domains in the world. This leads to a skewed focus in cross- linguistic research and MT development in particular where sufficient amounts of real-world examples of reasonable quality are only available for a few well- resourced languages.