A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 China and Britain: A Theme of National Liberation 1. G.C. Allen and Audrey G. Donnithorne, Western Enterprise in Far Eastern Economic Development: China and Japan, 1954, pp. 265-68; Cheng Yu-kwei, Foreign Trade and Industrial Development of China, 1956, p. 8. 2. Wu Chengming, Di Guo Zhu Yi Zai Jiu Zhong Guo De Tou Zi (The Investments of Imperialists in Old China), 1958, p. 41. 3. Jerome Ch'en, China and the West, p. 207. See also W. Willoughby, Foreign Rights and Interests in China, vol. 2, 1927, pp. 544-77, 595-8, 602-13. 4. Treaty of Tientsin, Art. XXXVII, in William F. Mayers, Treaties Between the Empire of China and Foreign Powers, 1906, p. 17. 5. Shang Hai Gang Shi Hua (Historical Accounts of the Shanghai Port), 1979, pp. 36-7. 6. See Zhao Shu-min, Zhong Guo Hai Guan Shi (History of China's Maritime Customs), 1982, pp. 22-46. With reference to the Chinese authorities' agreement to foreign inspectorate, see W. Willoughby, op.cit., vol. 2, pp. 769-70. 7. See S.F. Wright, China's Struggle for Tariff Autonomy, 1938; Zhao Shu-min, op. cit. pp. 27-38. 8. See Liu Kuang-chiang, Anglo-American Steamship Rivalry in China, 1862-1874, 1962; Charles Drage, Taikoo, 1970; Colin N. Crisswell, The Taipans, Hong Kong Merchant Princes, 1981. See also Historical Ac counts of the Shanghai Port, pp. 193-240; Archives of the China Mer chant's Steam Navigation Company, Maritime Transport Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Transport, Shanghai. 9. -

Young Galeano Writing About New China During the Sino-Soviet Split

Doubts and Puzzles: Young Galeano Writing about New China during the Sino-Soviet Split _____________________________________________ WEI TENG SOUTH CHINA NORMAL UNIVERSITY Abstract As a journalist of Uruguay’s Marcha weekly newspaper, Eduardo Galeano visited China in September 1963; he was warmly received by Chinese leaders including Premier Zhou Enlai. At first, Galeano published some experiences of his China visit in Marcha. In 1964, he published the complete journal of the trip, under the title of China, 1964: crónica de un desafío [“China 1964: Chronicle of a Challenge”]. Based on Chinese-language materials, this paper explores Galeano’s trip to China at that time and includes a close reading of Galeano’s travel notes. By analyzing his views on the New China, Socialism, and the Sino-Soviet Split, we will try to determine whether this China visit influenced his world view and cultural concepts. Keywords: Galeano, The New China, Sino-Soviet Split Resumen Como periodista del semanario uruguayo Marcha, Eduardo Galeano visitó China en septiembre de 1963 donde fue calurosamente recibido por los líderes chinos, incluido el Primer Ministro Zhou Enlai. Al principio, Galeano publicó algunas experiencias de su visita a China en Marcha. En 1964, publicó el diario completo del viaje bajo el título China, 1964: crónica de un desafío. Basado en materiales en chino, este artículo explora el viaje de Galeano e incluye una lectura detallada de sus notas. Por medio de un análisis de sus puntos de vista sobre la Nueva China, el socialismo y la ruptura sinosoviética, se intenta determinar si esta visita a China influyó en su visión del mundo y en sus conceptos culturales. -

Hannah Arendt's Question and Human Rights Debates in Mao's

Human Rights and Their Discontents: Hannah Arendt’s Question and Human Rights Debates in Mao’s China Wenjun Yu Human Rights and Their Discontents: Hannah Arendt’s Question and Human Rights Debates in Mao’s China Het onbehagen over mensenrechten: het probleem van Hannah Arendt en het debat over mensenrechten in het China van Mao (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 4 juli 2017 des middags te 12.45 uur door Wenjun Yu geboren op 3 april 1986 te Hubei, China Promotor: Prof.dr. I. de Haan Acknowledgements Writing a PhD dissertation is not a lonely work, I cannot finish this job without the generous help and supports from my supervisor, fellow PhD students, colleagues, friends and family. Although I take the complete responsibility for the content of this dissertation, I would like to thank all accompanies for their inspiration, encouragement, and generosity in the course of my PhD research. First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Ido de Haan for his continuous support of my PhD work at Utrecht University, for his great concern over my life in the Netherlands, for his generous encouragements and motivations when I was frustrated by many research problems, and particularly when I was stuck in the way of writing the dissertation during my pregnancy and afterwards. -

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People's Commune

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People’s Commune: Amateurism and Social Reproduction in the Maoist Countryside by Angie Baecker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Xiaobing Tang, Co-Chair, Chinese University of Hong Kong Associate Professor Emily Wilcox, Co-Chair Professor Geoff Eley Professor Rebecca Karl, New York University Associate Professor Youngju Ryu Angie Baecker [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0182-0257 © Angie Baecker 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Chang-chang Feng 馮張章 (1921– 2016). In her life, she chose for herself the penname Zhang Yuhuan 張宇寰. She remains my guiding star. ii Acknowledgements Nobody writes a dissertation alone, and many people’s labor has facilitated my own. My scholarship has been borne by a great many networks of support, both formal and informal, and indeed it would go against the principles of my work to believe that I have been able to come this far all on my own. Many of the people and systems that have enabled me to complete my dissertation remain invisible to me, and I will only ever be able to make a partial account of all of the support I have received, which is as follows: Thanks go first to the members of my committee. To Xiaobing Tang, I am grateful above all for believing in me. Texts that we have read together in numerous courses and conversations remain cornerstones of my thinking. He has always greeted my most ambitious arguments with enthusiasm, and has pushed me to reach for higher levels of achievement. -

A RE-EVALUATION of CHIANG KAISHEK's BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930S

A RE-EVALUATION OF CHIANG KAISHEK’S BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930s A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy DOOEUM CHUNG ProQuest Number: 11015717 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015717 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract Abstract This thesis considers the Chinese Blueshirts organisation from 1932 to 1938 in the context of Chiang Kaishek's attempts to unify and modernise China. It sets out the terms of comparison between the Blueshirts and Fascist organisations in Europe and Japan, indicating where there were similarities and differences of ideology and practice, as well as establishing links between them. It then analyses the reasons for the appeal of Fascist organisations and methods to Chiang Kaishek. Following an examination of global factors, the emergence of the Blueshirts from an internal point of view is considered. As well as assuming many of the characteristics of a Fascist organisation, especially according to the Japanese model and to some extent to the European model, the Blueshirts were in many ways typical of the power-cliques which were already an integral part of Chinese politics. -

Sino-Indian Relations, 1954-1962

Title Sino-Indian Relations, 1954-1962 Author(s) Lüthi, Lorenz Citation Eurasia Border Review, 3(Special Issue), 93-119 Issue Date 2012 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/50965 Type bulletin (article) File Information EBR3-S_009.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Sino-Indian Relations, 1954-1962 Lorenz Lüthi (McGill U., Montreal) Introduction Half a century ago, Sino-Indian relations moved from friendship to war within only five years. In June 1954, the two countries agreed on panch sheel, the five principles of coexistence. Sixty-two months later, they shot at each other across their unsettled border in the Himalayas. The attempt to sort out their differences during talks between their two prime ministers, Jawaharlal Nehru and Zhou Enlai, failed in April 1960. The downfall of Sino-Indian friendship was related to events in Tibet. The land between China proper and India was the source of most misunderstandings, and its unsettled borders the root for the wars in 1959 and 1962. But how did this development come about? Countless observers at the time and historians in retrospect have tried to trace the story. Partisans from both sides have attempted to show their own country in the best light. Responsibility and guilt have been shunted across the Himalayas in both directions. Even if the archival record is incomplete, original documentation from both sides and from other countries helps to shed some new light on the story. The problems that plagued the Sino-Indian relationship accumulated over the period from 1954 to early 1959. -

Taiwan's Struggle

The International History Review ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rinh20 Resisting Bandung? Taiwan’s Struggle for ‘Representational Legitimacy’ in the Rise of the Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League, 1954-57 Hao Chen To cite this article: Hao Chen (2021) Resisting Bandung? Taiwan’s Struggle for ‘Representational Legitimacy’ in the Rise of the Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League, 1954-57, The International History Review, 43:2, 244-263, DOI: 10.1080/07075332.2020.1762239 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2020.1762239 Published online: 06 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 282 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rinh20 THE INTERNATIONAL HISTORY REVIEW 2021, VOL. 43, NO. 2, 244–263 https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2020.1762239 Resisting Bandung? Taiwan’s Struggle for ‘Representational Legitimacy’ in the Rise of the Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League, 1954-57 Hao Chen Faculty of History, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In April 1955, representatives of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Anti-Communism; attended the Bandung Conference in Indonesia. The conference epito- Neutralism; mized the peak of Asian-African Internationalism, which sought to pur- Decolonization; Legitimacy sue independent and neutralist foreign policies that forged a path in- between the United States and the Soviet Union. This Conference helped the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) gain new ground in the ongoing struggle for ‘representational legitimacy’ against its rival the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese Nationalist Party) in the Third World. -

Journalist Biographie Archibald, John

Report Title - p. 1 of 303 Report Title Amadé, Emilio Sarzi (Curtatone 1925-1989 Mailand) : Journalist Biographie 1957-1961 Emilio Sarzi Amadé ist Korrespondent für Italien in China. [Wik] Archibald, John (Huntley, Aberdeenshire 1853-nach 1922) : Protestantischer Missionar, Journalist Biographie 1876-1913 John Archibald arbeitet für die National Bible Society of Scotland in Hankou. Er resit in Hubei, Hunan, Henan, Anhui und Jiangxi. [Who2] 1913 John Archibald wird Herausgeber der Central China post. [Who2] Bibliographie : Autor 1910 Archibald, John. The National Bible Society of Scotland. In : The China mission year book ; Shanghai (1910). [Int] Balf, Todd (um 2000) : Amerikanischer Journalist, Senior Editor Outside Magazine, Mitherausgeber Men's journal Bibliographie : Autor 2000 Balf, Todd. The last river : the tragic race for Shangi-la. (New York, N.Y. : Crown, 2000). [Erstbefahrung 1998 für die National Geographic Society durch wilde Schluchten des Brahmaputra (Tsangpo) in Tibet, die wegen Strömungen und Tod von Douglas Gordon (1956-1998) scheitert]. [WC,Cla] Balfour, Frederic Henry (1846-1909) : Kaufmann, Journalist in China Bibliographie : Autor 1876 Balfour, Frederic Henry. Waifs and strays from the Far East ; being a series of disconnected essays on matters relating to China. (London : Trübner, 1876). https://archive.org/details/waifsstraysfromf00balfrich. 1881 Chuang Tsze. The divine classsic of Nan-hua : being the works of Chuang Tsze, taoist philosopher. With an excursus, and copious annotations in English and Chinese by Frederic Henry Balfour. (Shanhgai ; Hongkong : Kelly & Walsh, 1881). [Zhuangzi. Nan hua jing]. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100328385. 1883 Balfour, Frederic Henry. Idiomatic dialogues in the Peking colloquial for the use of students. (Shanghai : Printed at the North-China Herald Office, 1883). -

Bull8-Cover Copy

220 COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN More New Evidence On THE COLD WAR IN ASIA Editor’s Note: “New Evidence on History Department (particularly Prof. Zhang Shuguang (University of Mary- the Cold War in Asia” was not only the Priscilla Roberts and Prof. Thomas land/College Park) played a vital liai- theme of the previous issue of the Cold Stanley) during a visit by CWIHP’s di- son role between CWIHP and the Chi- War International History Project Bul- rector to Hong Kong and to Beijing, nese scholars. The grueling regime of letin (Issue 6-7, Winter 1995/1996, 294 where the Institute of American Studies panel discussions and debates (see pro- pages), but of a major international (IAS) of the Chinese Academy of Social gram below) was eased by an evening conference organized by CWIHP and Sciences (CASS) agreed to help coor- boat trip to the island of Lantau for a hosted by the History Department of dinate the participation of Chinese seafood dinner; and a reception hosted Hong Kong University (HKU) on 9-12 scholars (also joining the CWIHP del- by HKU at which CWIHP donated to January 1996. Both the Bulletin and egation were Prof. David Wolff, then of the University a complete set of the the conference presented and analyzed Princeton University, and Dr. Odd Arne roughly 1500 pages of documents on the newly available archival materials and Westad, Director of Research, Norwe- Korean War it had obtained (with the other primary sources from Russia, gian Nobel Institute). Materials for the help of the Center for Korean Research China, Eastern Europe and other loca- Bulletin and papers for the conference at Columbia University) from the Rus- tions in the former communist bloc on were concurrently sought and gathered sian Presidential Archives. -

Searchable PDF Format

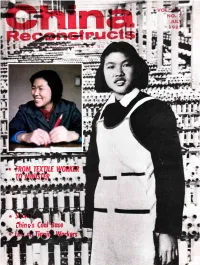

{ $: . $,: * *,: ax , $: $ ,,',$, ; l* * ? *r. s $ Ctr .:],.,l, ,tii{i I l'iittfi i tiitt* * ;ii t f . ' --" i] Mountains blt Cong Wenzhi PUBLISHED MONIHTY !!! ENGILSH, FRETIICH, SPAN|S}I, ARABIC,'cHrNG GERMAN, PoRTI,GUE5E AND cHlNEsE BY THE cHtNA WELFARE INsirrurE tsooNc Llnci, -CHArRrtiiiirl vol. xxx No. 7 JULY 1981 Artic tfie /l,{onth CONTENTS SOONG CHING LING 60 Yeors of the Chi- Named Honorary Chairman of the People's Republic nese Communist Porfy of China 3 Becomes Member of Chinese Communist Party a Speech: in Equality, For Peace 5 Canadian Award Marks Friendship 4 Politicol qn From Mill Hand to Minister 6 Thoughts on Thoughts on an Anniversary 10 Anniversory Major Events ln the Chinese Communist Party's 60 Years 13 Sidelights in Chlno, old ond Economic Shanxi Province China's Largest Coal Base 16 Economic Results- in 1980 (Charts) 24 throughout. Poge f0 Workers' Living Standards in Tianjin 45 Wang Jinling, the Soybean King 57 SOONG CHING IING Educotion/Scien ce Eminent stoteswomon becomes member ol the A Liberal Arts College Founded by the People 60 Chinese Communist Porly ond Honorory Choirmon Xiamen (Amoy) University's Overseas Correspondence of the People's Republic of Chino. 'lln Equolity, For College 33 Peoce", her most recent speech. Mount Gongga Biologists' Paradise 34 - From Textile Worker Minister Culture to 2,000 Years of Chinese Pagodas 27 The textile worker Hoo Hongkong Photographer Exhibits in Beijing 42 Jionxiu, obout whom Tianjin Collectors Donate Art Treasures to the State 62 Chino Reconstructs first wrote in 1952 wtren Medicine/Society she wos o girl of t7 ond A Woman Plastic Surgeon 32 imented o new method Active Life for the Handicapped 48 in cotton spinning, wos Sports Meet for the Blind and Deaf-Mutes 50 recently oppointed Chino's Minister of Tex. -

Kampen MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI and the CHINESE COMMUNIST

Kampen MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST LEADERSHIP MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI Thomas Kampen MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST LEADERSHIP NIAS AND THE EVOLUTION OF This book analyses the power struggles within the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party between 1931, when several Party leaders left Shanghai and entered the Jiangxi Soviet, and 1945, by which time Mao Zedong, Liu THE CHINESE COMMUNIST Shaoqi and Zhou Enlai had emerged as senior CCP leaders. In 1949 they established the People's Republic of China and ruled it for several decades. LEADERSHIP Based on new Chinese sources, the study challenges long-established views that Mao Zedong became CCP leader during the Long March (1934–35) and that by 1935 the CCP was independent of the Comintern in Moscow. The result is a critique not only of official Chinese historiography but also of Western (especially US) scholarship that all future histories of the CCP and power struggles in the PRC will need to take into account. “Meticulously researched history and a powerful critique of a myth that has remained central to Western and Chinese scholarship for decades. Kampen’s study of the so-called 28 Bolsheviks makes compulsory reading for anyone Thomas Kampen trying to understand Mao’s (and Zhou Enlai’s!) rise to power. A superb example of the kind of revisionist writing that today's new sources make possible, and reminder never to take anything for granted as far as our ‘common knowledge’ about the history of the Chinese Communist Party is concerned.” – Michael Schoenhals, Director, Centre for East and Southeast Asian Studies, Lund University, Sweden “Thomas Kampen has produced a work of exceptional research which, through the skillful use of recently available Chinese sources, questions the accepted wisdom about the history of the leadership of the CCP. -

Original Works and Translations

170 Chinese translations of Western books about Modern China (published in the People’s Republic of China between 1949 and 1995) compiled by Thomas Kampen Alitto, Guy: The Last Confucian: Liang Shuming and the Chinese Dilemma of Modernity, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979 / Ai Kai: Zuihou yige rujia, Changsha: Hunan renmin chubanshe, 1988 / Ai Kai: Zuihou de rujia, Nanjing: Jiangsu renmin chubanshe, 1993. (Haiwai Zhongguo yanjiu congshu). Arkush, R. David: Fei Xiaotong and Sociology in revolutionary China, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981 / Agushe: Fei Xiaotong zhuan, Beijing: Shishi chubanshe, 1985. Asiaticus: Von Kanton bis Shanghai 1926-1927, Berlin: Agis Verlag, 1928 / Xibo: "Cong Guangzhou dao Shanghai", in: Xibo wenji, Jinan: Shandong renmin chubanshe, 1986. Barilich, Eva: Fritz Jensen - Arzt an vielen Fronten, Wien: Globus Verlag, 1991 / Baliliqi: Yan Peide zhuan, Beijing: Xinhua chubanshe, 1992. Barrett, David D.: Dixie Mission, Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, 1970 / D. Baoruide: Meijun guanchazu zai Yan'an, Beijing: Jiefangjun chubanshe, 1984. Behr, Edward: The Last Emperor, Toronto: Bantam Books, 1987 / Beier: Zhongguo modai huangdi, Beijing: Zhongguo jianshe chubanshe, 1989. Belden, Jack: China shakes the world, New York: Harper, 1949 / Jieke Beierdeng: Zhongguo zhenhan shijie, Beijing: Beijing chubanshe, 1980. Bergere, Marie-Claire: L'âge d'or de la bourgeoisie chinoise, Paris: Flammarion, 1986 / Baijier: Zhongguo zichanjieji de huangjin shidai, Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1994. Bernal, Martin: Chinese Socialism to 1907, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1976 / Bonaer: 1907 nian yiqian Zhongguo de shehuizhuyi sichao, Fuzhou: Fujian renmin chubanshe, 1985. Bernstein, Thomas P.: Up to the mountains and down to the villages, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977 / Tuomasi Boensitan: Shangshan xiaxiang, Beijing: Jingguan jiaoyu chubanshe, 1993.