Changes of the Chinese Communist Party's Ideology and Reform Since

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

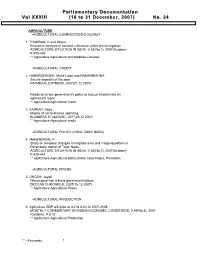

Parliamentary Documentation

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

New Trends in Mao Literature from China

Kölner China-Studien Online Arbeitspapiere zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas Cologne China Studies Online Working Papers on Chinese Politics, Economy and Society No. 1 / 1995 Thomas Scharping The Man, the Myth, the Message: New Trends in Mao Literature From China Zusammenfassung: Dies ist die erweiterte Fassung eines früher publizierten englischen Aufsatzes. Er untersucht 43 Werke der neueren chinesischen Mao-Literatur aus den frühen 1990er Jahren, die in ihnen enthaltenen Aussagen zur Parteigeschichte und zum Selbstverständnis der heutigen Führung. Neben zahlreichen neuen Informationen über die chinesische Innen- und Außenpolitik, darunter besonders die Kampagnen der Mao-Zeit wie Großer Sprung und Kulturrevolution, vermitteln die Werke wichtige Einblicke in die politische Kultur Chinas. Trotz eindeutigen Versuchen zur Durchsetzung einer einheitlichen nationalen Identität und Geschichtsschreibung bezeugen sie auch die Existenz eines unabhängigen, kritischen Denkens in China. Schlagworte: Mao Zedong, Parteigeschichte, Ideologie, Propaganda, Historiographie, politische Kultur, Großer Sprung, Kulturrevolution Autor: Thomas Scharping ([email protected]) ist Professor für Moderne China-Studien, Lehrstuhl für Neuere Geschichte / Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas, an der Universität Köln. Abstract: This is the enlarged version of an English article published before. It analyzes 43 works of the new Chinese Mao literature from the early 1990s, their revelations of Party history and their clues for the self-image of the present leadership. Besides revealing a wealth of new information on Chinese domestic and foreign policy, in particular on the campaigns of the Mao era like the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution, the works convey important insights into China’s political culture. In spite of the overt attempts at forging a unified national identity and historiography, they also document the existence of independent, critical thought in China. -

Beijing Sets the Stage to Convene the 16Th Party Congress

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No.4 Beijing Sets the Stage to Convene the 16th Party Congress H. Lyman Miller After a summer of last-minute wrangling, Beijing moved swiftly to complete preparations for the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 16th Party Congress. Since the leadership’s annual summer retreat at the north China seaside resort at Beidaihe, leadership statements and authoritative press commentary have implied that the congress, scheduled to open on November 8, 2002, will see the long-anticipated retirement of “third generation” leaders around party General Secretary Jiang Zemin and the installation of a new “fourth generation” leadership led by Hu Jintao. Chinese press commentary has also indicated that the party constitution will be amended to incorporate the “three represents”--the controversial political reform enunciated by Jiang Zemin nearly three years ago which aims to broaden the party’s base by admitting the entrepreneurial, technical, and professional elite that has emerged in Chinese society under two decades of economic reform. The relative clarity of political trends since the Beidaihe leadership retreat contrasts starkly with their uncertainty immediately preceding it. Weeks before the annual Beidaihe leadership retreat, a torrent of rumors erupted in Beijing and found voice in the noncommunist Hong Kong and foreign press alleging that Jiang Zemin was having second thoughts about the congress. For unclear reasons that were nevertheless widely speculated upon, Jiang was said to be retreating from long-established plans for succession and seeking to retain some or all of his top posts. In addition, opposition among the party’s rank and file to the proposed incorporation of the three represents into the party constitution remained strong, despite two years’ worth of efforts by the party leadership to dispel it.1 The course of leadership discussions at Beidaihe cannot be assessed with any certainty. -

Mao Zedong's Rise to Power: How One Man Changed the Future for the Better; Then Changed It for Himself

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Mao Zedong's Rise to Power: How One Man Changed the Future for the Better; then Changed it for Himself Shadeed Haneef Ali II Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Ali, Shadeed Haneef II, "Mao Zedong's Rise to Power: How One Man Changed the Future for the Better; then Changed it for Himself" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 237. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/237 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mao Zedong’s Rise to Power: How One Man Changed the Future for the Better, then Changed it for Himself Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Asian Studies Of Bard College By Shadeed Haneef Ali II Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Have We not opened your breast for you? And We removed from you your burden, Which weighed down your back? And We exalted for you your reputation? So verily, with the hardship, there is relief, Verily, with the hardship, there is relief So when you have finished, then stand up for Allah's worship And to Allah turn your invocations. -

Heretics of China. the Psychology of Mao and Deng

HERETICS OF CHINA HERETICS OF CHINA THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MAO AND DENG NABIL ALSABAH URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-445061 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20378/irbo-44506 Copyright © 2019 by Nabil Alsabah Cover design by Katrin Krause Cover illustration by Daiquiri/Shutterstock.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. ISBN: 978-1-69157-995-2 Created with Vellum During his years in power, Mao Zedong initiated three policies which could be described as radical departures from Soviet and Chinese Communist practice: the Hundred Flowers of 1956-1957, the Great Leap Forward 1958-1960, and the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. Each was a disaster: the first for the intellectuals, the second for the people, the third for the Party, all three for the country. — RODERICK MACFARQUHAR, THE SECRET SPEECHES OF CHAIRMAN MAO In many ways, [Deng Xiaoping’s] reputation is underestimated: while Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev oversaw the peaceful end of Soviet communist rule and the dismembering of the Soviet empire, he had wanted to keep the Soviet Union in place and reform it. Instead it fell apart; communism lost power—and Russia endured a decade of instability […]. Perhaps the most influential political titan of the late 20th century, Deng succeeded in guiding China towards his vision where his fellow communist leaders failed. — SIMON SEBAG MONTEFIORE, TITANS OF HISTORY CONTENTS Introduction ix 1. -

Falun Gong in the United States: an Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-18-2003 Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Porter, Noah, "Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study" (2003). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALUN GONG IN THE UNITED STATES: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY by NOAH PORTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: S. Elizabeth Bird, Ph.D. Michael Angrosino, Ph.D. Kevin Yelvington, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 18, 2003 Keywords: falungong, human rights, media, religion, China © Copyright 2003, Noah Porter TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................... -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

International Security 24:1 66

China’s Search for a John Wilson Lewis Modern Air Force and Xue Litai For more than forty- eight years, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has sought to build a combat-ready air force.1 First in the Korean War (1950–53) and then again in 1979, Beijing’s leaders gave precedence to this quest, but it was the Gulf War in 1991 coupled with growing concern over Taiwan that most alerted them to the global revolution in air warfare and prompted an accelerated buildup. This study brieºy reviews the history of China’s recurrent efforts to create a modern air force and addresses two principal questions. Why did those efforts, which repeatedly enjoyed a high priority, fail? What have the Chinese learned from these failures and how do they deªne and justify their current air force programs? The answers to the ªrst question highlight changing defense con- cerns in China’s national planning. Those to the second provide a more nu- anced understanding of current security goals, interservice relations, and the evolution of national defense strategies. With respect to the ªrst question, newly available Chinese military writings and interviews with People’s Liberation Army (PLA) ofªcers on the history of the air force suggest that the reasons for the recurrent failure varied markedly from period to period. That variation itself has prevented the military and political leaderships from forming a consensus about the lessons of the past and the policies that could work. In seeking to answer the second question, the article examines emerging air force and national defense policies and doctrines and sets forth Beijing’s ra- tionale for the air force programs in light of new security challenges, particu- larly those in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. -

Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers"

Vol. 26, No. 33 August 15, 1983 EIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EW NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers" Military Leader's Works Published Beijing Plans Urban Development Interestingly, when many mem- don't mean that there isn't room bers read the article which I for improvement. LETTERS brought to one of our sessions, a Alejandreo Torrejon M. desire was expressed to explore Sucre, Bolivia Retirement the possibility of visiting China for the very purpose of sharing Once again, I write to commend our ideas with people in China. Documents you for a most interesting and, to We are in the midst of doing just People like us who follow the me, a most meaningful article that. Thus, your magazine has developments in China only by dealing with retirees ("When borne some unexpected fruit. reading your articles cannot know Leaders or Professionals Retire," if the Sixth Five-Year Plan issue No. 19). It is a credit to Louis P. Schwartz ("Documents," issue No. 21) is ap- your social approach that yQu are New York, USA plicable just by glancing over it. examining the role of profes- However, it is still a good article sionals, administrators and gov- with reference value for people ernmental leaders with an eye to Chinese-Type Modernization who want to observe and follow what they can expect when they China's developments. I plan to leave the ranks of direct workin~ The series of articles on Chi- read it over again carefully and people and enter the ranks of "re- nese-Type Modernization and deepen my understanding. -

Reflections on 40 Years of China's Reforms

Reflections on Forty Years of China’s Reforms Speech at the Fudan University’s Fanhai School of International Finance January 2018 Bert Hofman, World Bank1 This conference is the first of undoubtedly many that will commemorate China’s 40 years of reform and opening up. In December 2018, it will have been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping kicked off China’s reforms with his famous speech “Emancipate the mind, seeking truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future,” which concluded that year’s Central Economic Work Conference and set the stage for the 3rd Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The speech brilliantly used Mao Zedong’s own thoughts to depart from Maoism, rejected the “Two Whatevers” of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng (“Whatever Mao said, whatever Mao did”), and triggered decades of reforms that would bring China where it is now—the second largest economy in the world, and one of the few countries in the world that will soon2 have made the journey from low income country to high income country. This 40th anniversary is a good time to reflect on China’s reforms. Understanding China’s reforms is of importance first and foremost for getting the historical record right, and this record is still shifting despite many volumes that have already been devoted to the topic. Understanding China’s past reforms and with it the basis for China’s success is also important for China’s future reforms—understanding the path traveled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers on where to go next. -

How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 Pp

44795_Book_Reviews:19016_Cato 8/29/13 11:56 AM Page 613 Book Reviews Readers searching for such hypothetical society-building will go away disappointed—and that, finally, is what Two Cheers is about. Such projects end in disappointment. That’s exactly what they always do. Jason Kuznicki Cato Institute How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 pp. In 1981, shortly after China began to liberalize its economy, Steven N. S. Cheung predicted that free markets would trump state planning and eventually China would “go ‘capitalist’.” He grounded his analysis in property rights theory and the new institutional eco- nomics, of which he was a pioneer. Ronald Coase, a longtime profes- sor of law and economics at the University of Chicago and Cheung’s colleague during 1967–69, agreed with that prediction. Now the Nobel laureate economist has teamed up with Ning Wang, a former student and a senior fellow at the Ronald Coase Institute, to provide a detailed account of “how China became capitalist.” The hallmark of this book is the use of primary sources to provide an in-depth view of the institutional changes that took place during the early stages of China’s economic reforms and the use of Coaseian analysis to understand those changes. In particular, Coase’s distinc- tion between the market for goods and the market for ideas is applied to China’s reform movement and gives a fresh perspective of how China was able to make the transition from plan to market. The key conclusion is that the absence of a free market for ideas is a threat to China’s future development.