Hurst Diary, Hurst Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings Op the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting Op the Geological Society Op America, Held at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December 21, 28, and 29, 1910

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 22, PP. 1-84, PLS. 1-6 M/SRCH 31, 1911 PROCEEDINGS OP THE TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OP THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OP AMERICA, HELD AT PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA, DECEMBER 21, 28, AND 29, 1910. Edmund Otis Hovey, Secretary CONTENTS Page Session of Tuesday, December 27............................................................................. 2 Election of Auditing Committee....................................................................... 2 Election of officers................................................................................................ 2 Election of Fellows................................................................................................ 3 Election of Correspondents................................................................................. 3 Memoir of J. C. Ii. Laflamme (with bibliography) ; by John M. Clarke. 4 Memoir of William Harmon Niles; by George H. Barton....................... 8 Memoir of David Pearce Penhallow (with bibliography) ; by Alfred E. Barlow..................................................................................................................... 15 Memoir of William George Tight (with bibliography) ; by J. A. Bownocker.............................................................................................................. 19 Memoir of Robert Parr Whitfield (with bibliography by L. Hussa- kof) ; by John M. Clarke............................................................................... 22 Memoir of Thomas -

ED347887.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 347 887 HE 025 650 AUTHOR Gill, Wanda E. TITLE The History of Maryland's Historically Black Colleges. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 57p. PUB TYPE Historical MatPrials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Black Colleges; Black History; Black Students; *Educational History; Higher Education; Racial Bias; Racial Segregation; School Desegregation; State Colleges; State Legislation; State Universities; Whites IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; Bowie State College MD; Coppin State College MD; *Maryland; Morgan State University MD; University of Maryland Eastern Shore ABSTRACT This paper presents a history of four historically Black colleges in Maryland: Bowie State University, Coppin State College, Morgan State University, and the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore. The history begins with a section on the education of Blacks before 1800, a period in which there is little evidence of formal education for African Americans despite the presence of relatively large numbers of free Blacks thronghout the state. A section on the education of Blacks from 1800 to 1900 describes the first formal education of Blacks, the founding of the first Black Catholic order of nuns, and the beginning of higher education in the state after the Civil War. There follow sections on each of the four historically Black institutions in Maryland covering the founding and development of each, and their responses to social changes in the 1950s and 1960s. A further chapter describes the development and manipulation of the Out of State Scholarship Fund which was established to fund Black students who wished to attend out of state institutions for courses offered at the College Park, Maryland campus and other White campuses from which they were barred. -

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences VOLUME 29 1983 NUMBER 1 A SYSTEMATIC STUDY OF TWO SPECIES COMPLEXES OF THE GENUS FUNDULUS (PISCES: CYPRINODONTIDAE) KENNETH RELYEA e UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. OLIVER L. AUSTIN, JR., Editor RHODA J. BRYANT, Managing Editor Consultants for this issue: GEORGE H. BURGESS ~TEVEN P. (HRISTMAN CARTER R. GILBERT ROBERT R. MILLER DONN E. ROSEN Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manuscripts should be addressed to: Managing Editor, Bulletin; Florida State Museum; University of Florida; Gainesville, FL 32611, U.S.A. Copyright © by the Florida State Museum of the University of Florida This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $3,300.53, or $3.30 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researches in the natural sciences, emphasizing the circum-Caribbean region. Publication dates: 22 April 1983 Price: $330 A SYSTEMATIC STUDY OF TWO SPECIES COMPLEXES OF THE GENUS FUNDULUS (PISCES: CYPRINODONTIDAE) KENNETH RELYEAl ABSTRACT: Two Fundulus species complexes, the Fundulus heteroctitus-F. grandis and F. maialis species complexes, have nearly identical Overall geographic ranges (Canada to north- eastern Mexico and New England to northeastern Mexico, respectively; both disjunctly in Yucatan). Fundulus heteroclitus (Canada to northeastern Florida) and F. grandis (northeast- ern Florida to Mexico) are valid species distinguished most readily from one another by the total number of mandibular pores (8'and 10, respectively) and the long anal sheath of female F. -

An Analysis of Institutional Responsibilities for the Long-Term

AN ANALYSIS OF INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES FOR THE LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT OF CONTAMINANT ISOLATION FACILITIES By Kevin M. Kostelnik Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Interdisciplinary Studies: Environmental Management May, 2005 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor James Clarke Professor David Kosson Professor Jerry Harbour Professor Mark Abkowitz Professor Mark Cohen Professor Michael Vandenbergh Copyright © 2005 by Kevin M. Kostelnik All Rights Reserved To Mom and Dad for a lifetime of encouragement and support and As inspiration to Colton, Samantha and future generations. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research would not have been possible without the financial support of the U.S. Department of Energy, the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory and the Consortium for Risk Evaluation with Stakeholder Participation. I would like to thank the management team and staff at the INEEL for the opportunity to conduct this work. In particular, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Paul Kearns, the former INEEL Laboratory Director, for his support and personal encouragement. The completion of this research would not have been possible without the support and contributions of many friends and colleagues. First, I would like to acknowledge the very positive support and academic excellence of my Dissertation Committee. I thank them for their enthusiasm and guidance throughout this research. I appreciate the assistance of the case study points of contact whose personal insights and access to information strengthened the content of the case study reports. I would like to acknowledge the graphics support of Allen Haroldsen and the editing support of Eric Swisher. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Professionalizing Science and Engineering Education in Late- Nineteenth Century America Paul Nienkamp Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 A culture of technical knowledge: professionalizing science and engineering education in late- nineteenth century America Paul Nienkamp Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other History Commons, Science and Mathematics Education Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Nienkamp, Paul, "A culture of technical knowledge: professionalizing science and engineering education in late-nineteenth century America" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15820. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15820 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A culture of technical knowledge: Professionalizing science and engineering education in late-nineteenth century America by Paul Nienkamp A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: History of Technology and Science Program of Study Committee: Amy Bix, Co-major Professor Alan I Marcus, Co-major Professor Hamilton Cravens Christopher Curtis Charles Dobbs Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Paul Nienkamp, 2008. All rights reserved. 3316176 3316176 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION – SETTING THE STAGE FOR NINETEENTH CENTURY ENGINEERING EDUCATION 1 CHAPTER 2. EDUCATION AND ENGINEERING IN THE AMERICAN EAST 15 The Rise of Eastern Technical Schools 16 Philosophies of Education 21 Robert Thurston’s System of Engineering Education 36 CHAPTER 3. -

A Bubble of the American Dream: Experiences of Asian Students at Key Universities in the Midst of Racist Movements in Progressive-Era California

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 24 Article 8 2019 A Bubble of the American Dream: Experiences of Asian students at key universities in the midst of racist movements in Progressive-Era California Chang Woo Lee Santa Clara Univeristy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Chang Woo (2019) "A Bubble of the American Dream: Experiences of Asian students at key universities in the midst of racist movements in Progressive-Era California," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 24 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol24/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: A Bubble of the American Dream A Bubble of the American Dream: Experiences of Asian students at key universities in the midst of racist movements in Progressive-Era California Chang Woo Lee One way of summing up the past two years of the Trump presidency is the fight against immigrants: Trump attempted to end DACA and build a wall along the Mexico border. During his presidency, opportunities for legal immigration and visitation became stricter. California leads the resistance against this rising anti-immigrant sentiment as it strongly associates itself with diversity and immigration. -

Forestry Education at the University of California: the First Fifty Years

fORESTRY EDUCRTIOfl T THE UflIVERSITY Of CALIFORflffl The first fifty Years PAUL CASAMAJOR, Editor Published by the California Alumni Foresters Berkeley, California 1965 fOEUJOD T1HEhistory of an educational institution is peculiarly that of the men who made it and of the men it has helped tomake. This books tells the story of the School of Forestry at the University of California in such terms. The end of the first 50 years oi forestry education at Berkeley pro ides a unique moment to look back at what has beenachieved. A remarkable number of those who occupied key roles in establishing the forestry cur- riculum are with us today to throw the light of personal recollection and insight on these five decades. In addition, time has already given perspective to the accomplishments of many graduates. The School owes much to the California Alumni Foresters Association for their interest in seizing this opportunity. Without the initiative and sustained effort that the alunmi gave to the task, the opportunity would have been lost and the School would have been denied a valuable recapitulation of its past. Although this book is called a history, this name may be both unfair and misleading. If it were about an individual instead of an institution it might better be called a personal memoir. Those who have been most con- cerned with the task of writing it have perhaps been too close to the School to provide objective history. But if anything is lost on this score, it is more than regained by the personalized nature of the account. -

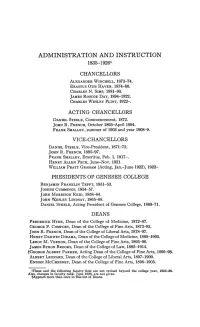

Administration and Instruction 1835-19261

ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION 1835-19261 CHANCELLORS ALEXANDER WINCHELL, 1873-74. ERASTUS OTIS H~VEN, 1874-80. CHARLES N. SIMS, 1881-93. ]AMES RoscoE DAY, 1894-1922. CHARLES WESLEY FLINT, 1922-. ACTING CHANCELLORS DANIEL STEELE, Commencement, 1872. ]OHN R. FRENCH, October 1893-April1894. FRANK SMALLEY, summer of 1903 and year 1908-9. VICE-CHANCELLORS D~NIEL STEELE, Vice-President, 1871-72. ]OHN R. FRENCH, 1895-97. FRANK SMALLEY, Emeritus, Feb. 1, 1917-. HENRY ALLEN PECK, June-Nov. 1921. WILLIAM PR~TT GRAHAM (Acting, Jan.-June 1922), 1922- :PRESIDENTS OF GENESEE COLLEGE BENJAMIN FRANKLIN TEFFT, 1851-53. JosEPH CuMMINGs, 1854-57. JOHN MoRRISON REID, 1858-64. ]OHN WESLEY LINDSAY, 1865-68. DANIEL STEELE, Acting President of Genesee College, 1869-71. DEANS FREDERICK HYDE, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1872-87. GEORGE F. CoMFORT, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1873-93. JOHN R. FRENCH, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1878-97. HE~RY DARWIN DIDAMA, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1888-1905. LEROY M. VERNON, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1893-96. ]AMES BYRON BROOKS, Dean of the College of Law, 1895-1914. tGEORGE ALBERT PARKER, Acting Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1896-98. ALBERT LEONARD, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1897-1900. ENSIGN McCHESNEY, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1898-1905. IThese and the following faculty lists are not revised beyond the college year, 1925-26. Also, changes in faculty rank, June 1926, are not given. tAppears more than once in this list of Deans. ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION-DEANS Io69 FRANK SMALLEY, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts (Acting, Sept. -

United Methodist Bishops Page 17 Historical Statement Page 25 Methodism in Northern Europe & Eurasia Page 37

THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA BOOK of DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2009 Copyright © 2009 The United Methodist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may reproduce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Northern Europe & Eurasia Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2009. Copyright © 2009 by The United Method- ist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. Used by permission.” Requests for quotations that exceed 1,000 words should be addressed to the Bishop’s Office, Copenhagen. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Name of the original edition: “The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church 2008”. Copyright © 2008 by The United Methodist Publishing House Adapted by the 2009 Northern Europe & Eurasia Central Conference in Strandby, Denmark. An asterisc (*) indicates an adaption in the paragraph or subparagraph made by the central conference. ISBN 82-8100-005-8 2 PREFACE TO THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA EDITION There is an ongoing conversation in our church internationally about the bound- aries for the adaptations of the Book of Discipline, which a central conference can make (See ¶ 543.7), and what principles it has to follow when editing the Ameri- can text (See ¶ 543.16). The Northern Europe and Eurasia Central Conference 2009 adopted the following principles. The examples show how they have been implemented in this edition. -

Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com JuliaWardHowe,1819-1910 LauraElizabethHoweRichards,MaudElliott,FlorenceHall ? XL ;,. •aAJMCMt 1 Larffe=|)aper (BUttion JULIA WARD HOWE 1819-1910 IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II it^tTWe new v- *v ch^A^^ /r^^t^ (TLs-tstrt^ Mrs. Howe, 1895 JULIA WARD HOWE 1819-1910 BY LAURA E. RICHARDS and MAUD HOWE ELLIOTT ASSISTED BY FLORENCE HOWE HALL With Portraits and other Illustration* VOLUME n BOSTON AND, NEW YORJK ;*.'. / HOUGHTON MIFELttJ :V COMPANY 1915 THF. N -W YOP.K PUBLIC LIBRARY 73 1. H« 1 f * AST OR IR, LE NOX AND TILDE N FOUr.CjAl IONS I 1916 LJ COPYRiGHT, i9i5, BY LAURA E. RiCHARDS AND MAUD HOWE ELLiOTT ALL RiGHTS RESERVED Published December lt)lj CONTENTS I. EUROPE REVISITED. 1877 3 II. A ROMAN WINTER. 1878-1879 28 III. NEWPORT. 1879-1882 46 IV. 841 BEACON STREET: THE NEW ORLEANS EXPOSITION. 1883-1885 80 V. MORE CHANGES. 1886-1888 115 VI. SEVENTY YEARS YOUNG. 1889-1890 143 VH. A SUMMER ABROAD. 1892-1893 164 VDJ. "DIVERS GOOD CAUSES." 1890-1896 186 IX. IN THE HOUSE OF LABOR. 1896-1897 214 X. THE LAST ROMAN WINTER. 1897-1898 237 XI. EIGHTY YEARS. 1899-1900 258 XII. STEPPING WESTWARD. 1901-1902 282 XIII. LOOKING TOWARD SUNSET. 190S-1905 308 XIV. "THE SUNDOWN SPLENDID AND SERENE." 1906-1907 342 XV. "MINE EYES HAVE SEEN THE GLORY OF THE COMING OF THE LORD." 1908-1910 369 INDEX 415 ILLUSTRATIONS Mas. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M. Sackler Museum. In this allegorical portrait, America is personified as a white marble goddess. Dressed in classical attire and crowned with thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies, the figure gives form to associations Americans drew between their democracy and the ancient Greek and Roman republics. Like most nineteenth-century American marble sculptures, America is the product of many hands. Powers, who worked in Florence, modeled the bust in plaster and then commissioned a team of Italian carvers to transform his model into a full-scale work. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Powers’s studio in 1858, captured this division of labor with some irony in his novel The Marble Faun: “The sculptor has but to present these men with a plaster cast . and, in due time, without the necessity of his touching the work, he will see before him the statue that is to make him renowned.” Identification and Creation Object Number 1958.180 People Hiram Powers, American (Woodstock, NY 1805 - 1873 Florence, Italy) Title America Other Titles Former Title: Liberty Classification Sculpture Work Type sculpture Date 1854 Places Creation Place: North America, United States Culture American Persistent Link https://hvrd.art/o/228516 Location Level 2, Room 2100, European and American Art, 17th–19th century, Centuries of Tradition, Changing Times: Art for an Uncertain Age. Signed: on back: H. Powers Sculp. Henry T. Tuckerman, Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists, Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America , Putnam (New York, NY, 1867), p.