University Microfilms International300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miriam Elman CV

MIRIAM F. ELMAN, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Political Science Inaugural Robert D. McClure Professor of Teaching Excellence Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs Syracuse University SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY POSITIONS: ■ Research Director: Program for the Advancement of Research on Conflict and Collaboration (PARCC) ■ Member of the Advisory Board and Steering Committee: Jewish Studies Program (JSP) | Middle Eastern Studies Program (MESP) ■ Faculty Affiliate: Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism (INSCT) PREVIOUS POSITIONS: Associate & Assistant Professor Department of Political Science, Arizona State University (1996-2008) Faculty Affiliate Jewish Studies Program, Arizona State University (1996-2008) Instructor Department of Political Science, Arizona State University (1995-1996) Research Fellow Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University (1995-1996 and 1998-2000) Sergeant, Air Force, Israel Defense Forces (1983-1985) CONTACT INFORMATION: 400G Eggers Hall Syracuse, New York, 13244-1020 Tel: 315-443-7404 Fax: 315-443-9082 Email: [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA: Webpage Twitter Facebook Columns at Legal Insurrection 2 EDUCATION 1996 Ph.D. Columbia University Political Science 1993 M.Phil. Columbia University Political Science 1990 M.A. Degree Studies Hebrew University International Relations of Jerusalem, Israel 1989 Secondary School Hebrew University Teaching Certificate of Jerusalem, Israel 1988 B.A. (cum laude) Hebrew University International Relations -

Sail Training, Vocational Socialisation and Merchant Seafarer Careers: the German Initiative in the 1950S1 Alston Kennerley

Sail Training, Vocational Socialisation and Merchant Seafarer Careers: The German Initiative in the 1950s1 Alston Kennerley Tout au long du 20ème siècle la pertinence de l'expérience pratique dans les navires hauturiers à voile carrée avec de futures carrières de marin dans les navires motorisés a été discutée et remise en cause. Il restent aujourd'hui des pays qui fournissent une telle expérience pour des officiers stagiaires, et il y a un soutien mondial pour donner de l'expérience de la voile aux jeunes dans le cadre du développement caractériel indépendamment du futur métier. La discussion ici se concentre sur l'initiative allemande des années 50, en recherchant des avis personnels au sujet du contexte et du but opérationnel, par le moyen de questionnaires sur l'expérience personnelle de la voile et du métier de marin qui a pu suivre. Les résultats prouvent que les répondants étaient généralement favorables à la possibilité de formation en termes de la gamme étendue des qualifications personnelles engendrées, et que le coût et l'effort sont valables. The history of merchant seafarer training is probably almost as old as deep sea seafaring itself. It can certainly be identified from medieval times, at least in Britain through the adoption of craft guild progression structures: apprenticeship, journeyman craftsman (mate), master craftsman. In British seafaring two levels of apprenticeship evolved: seaman apprenticeship and officer apprenticeship. With the opening of the oceans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, educational dimensions, especially navigation, began to be taught ashore as well as at sea, to those destined for command. Until well into the nineteenth century, skills aspects, grouped under the term seamanship, were always learned or taught through example and experience aboard ships engaged in commercial trading. -

2005 Orange Football Game #5 – Syracuse Vs

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY 2005 ORANGE FOOTBALL GAME #5 – SYRACUSE VS. CONNECTICUT • OCTOBER 7, 2005 SYRACUSE (1-3 overall, 0-1 BIG EAST) Rentschler Field (40,000) East Hartford, Conn. vs. October 7, 2005 CONNECTICUT (3-1 overall, 0-0 BIG EAST) 8:00 p.m. • ESPN2 On the Air ANY RHODES YOU CHOOSE Senior tailback Damien Rhodes (Manlius, Backs in the Passing Game Television N.Y.) has been the Orange’s top offensive ESPN2 will broadcast the Syracuse game By Receptions threat on the ground and catching balls Player Rec. Years at Connecticut … Dave Pasch, Trevor through the air … He had 70 receiving yards Duane Kinnon 61 1988-90 Matich and Rodney Gilmore will call the and 44 rushing yards for a total of 114 all- Jaime Covington 60 1981-84 action, and Stacy Dales-Schuman will Walter Reyes 59 2001-04 purpose yards against Florida State … The Brent Ziegler 50 1980-83 provide sideline reports … Kim Belton will performance moved him into ninth on SU’s Floyd Little 50 1964-66 produce the broadcast. Damien Damien Rhodes 49 2002- Rhodes all-purpose yards list, passing Orange legend Radio Ernie Davis and James Mungro with 3, 331 … By Yards Syracuse ISP Sports Network His 70 yards receiving also moved him into third all-time Player Yards Years Duane Kinnon 629 1988-90 The flagship station for the Syracuse ISP in receiving yards by a running back at SU … Rhodes’ 49 career receptions by a runner is one shy of Floyd Little Floyd Little 582 1964-66 Sports Network is WAQX-95.7FM … Voice Damien Rhodes 552 2002- of the Orange Matt Park and analyst and Brent Ziegler -

Schuder, Ted TITLE Teachers' First Year of Transactional Strategies Instruction

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 362 853 CS 011 449 AUTHOR El-Dinary, Pamela Beard; Schuder, Ted TITLE Teachers' First Year of Transactional Strategies Instruction. Reading Research Report No. 5. INSTITUTION National Reading Research Center, Athens, GA.; National Reading Research Center, College Park, MD. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 93 CONTRACT 117A20007 NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE 14F01/12CO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Education; Inservice Teacher Education; Program Effectiveness; *Reading Instruction; Reading Research; *Teacher Attitudes; *Teacher Response; Teaching Methods; Teaching Styles IDENTIFIERS *Transactional Strategies Instruction ABSTRACT Two studies examined seven teachers' acceptance of a strategies-based approach to reading instruction during their first year of using the intervention. Interviews andobservations revealed that the intervention, a long-term transactional strategies instruction program called SAIL (Students Achieving Independent Learning), was fully acceptable to only two of the seven teachers. Issues that influenced acceptability included professional development support and teacher choice. Recommendations that could lead to greater acceptance of transactional strategies instruction by teachers using it for the first time are offered. Briefly, teachers need: several years of professional development; a safe, supportive school environment; explanations and modeling of what good strategy teachers do; and encouragement -

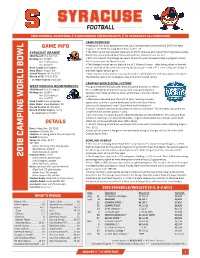

Bowl Notes.Indd

FOOTBALL 1959 NATIONAL CHAMPIONS // 5 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS // 18 CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICANS GAME OVERVIEW GAME INFO • Making its fi rst bowl appearance since 2013, Syracuse takes on former BIG EAST rival West Virginia in the 2018 Camping World Bowl on Dec. 28. SYRACUSE ORANGE • The matchup will be televised na onally on ESPN. Syracuse alum Dave Flemming (play-by-play), 2018 Record: 9-3, 6-2 ACC Rod Gilmore (analyst) and Quint Kessenich (sideline reporter) have the call. Ranking: No. 17 (AP) • With a 9-3 record, the Orange can reach 10 wins for just the seventh me in program history No. 17 (Coaches) with a victory over the Mountaineers. No. 20 (CFP) • The Orange clinched second place in the ACC Atlan c Division – a er being picked to fi nished Head Coach: Dino Babers last on that side of the conference during the preseason – with a 42-21 win at Boston College in Alma Mater: Hawaii '84 their last regular-season game. Overall Record: 54-35 (.607) • West Virginia, losers of their last two, fi nished in a third-place e with Iowa State in the Big 12. Record at SU: 17-19 (.472) The Mountaineers enter postseason play with an 8-3 overall record. vs. West Virginia: 0-0 (.000) CAMPING WORLD BOWL HISTORY WEST VIRGINIA MOUNTAINEERS • Originally tled the Blockbuster Bowl, the game was born in Miami, 2018 Record: 8-3, 6-3 Big 12 Fla., in 1990 and thrived in its fi rst year with a marquee matchup Ranking: No. 15 (AP) between Penn State and Florida State, which drew more than 74,000 No. -

2021-22 Algoma High School Course Handbook

HIGH SCHOOL 2021-2022 Table of Contents Credits……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Transfer Students…………………………………………………………………………..3 Graduation………………………………………………………………………………... 3 Class Load/Dropping Classes…………………………………………………………….. 3 Credit Recovery…………………………………………………………………………... 3 Graduation Requirements……………………………………………………………….... 4 College-Bound Athlete…………………………………………………………………… 5 Courses Taken in High School for College Credit….……………………………………. 6 NWTC Advanced Standing & Transcribed Credit….……………………………. 6 Cooperative Academic Partnership Program (CAPP)……………………………. 7 College Credit in High School (CCIHS) Program………………………………. 7 Courses Taken in Middle School for High School Credit……………………………….. 8 Algoma Middle School Scheduling Information.…………………………………………8 Course Delivery/Learning Format Definitions…………………………………………... 9 Course Offerings by Departments………………………………………………………... 9 English……………………………………………………………………………. 9 Social Studies/Social Sciences…………………………………………………...13 Science………………………..…………………………………………………. 17 Mathematics……………………………………………………………………...20 Health and Wellness Education…………………………………………..............23 Career and Technical Education……………………………………………….... 24 Business Education……………………………………………………… 24 Family and Consumer Science…………………………………………...26 Visual Arts………………………………………………………………. 28 Technology and Engineering Education……………………………….... 30 Foreign Language……………………………………………………………….. 31 Music Education………………………………………………………………… 32 Other Opportunities……………………………………………………………... 33 It is the policy of the School District of Algoma -

Comparing Sail Training and Landbased Youth Development Activities: a Pilot Study Luke Mccarthy and Ben Kotzee

Comparing sail training and landbased youth development activities: a pilot study Luke McCarthy and Ben Kotzee Introduction The value of adventure and experience of the outdoors to education and general personal development has long been stressed, with some authors tracing the idea as far as Homer and Plato (Hattie et al, 1987: 43). A more obvious history of adventure education can be traced from the Victorian era – with its romantic idealisation of the experience of nature (Hopkins and Putnam, 1993: 4) – to today. Whilst some of the effect of outdoor or adventure education programmes may lie in the positive impact of such programmes on physical fitness, experiencing the outdoors environment was seen (by both classical and Victorian authors) as an important factor in general social development. This view has been supported since from the 1960s onwards through a number of empirical studies that seek to justify the effectiveness of such programmes and that sketch exactly what the benefits of such programmes are (Ewert, 1987: 14). Using ships and the sea in adventure education also has a history that can be traced back to the mid-19th century (McCulluch, 2002: 70). By the mid-20th century “sail- training” had become more formalised, with, for instance, the establishment of the (UK) Sail Training Association (now the Tall Ships Youth Trust) and the International Sail Training Association (both in 1956). Today, there are more than 30 organisations in the UK alone providing sail training on more than 50 craft. The primary purpose of these organisations is not necessarily to teach young people to sail, but rather to develop life skills more generally through involvement with sailing. -

2005 Orange Football Game #10 • Syracuse Vs

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY 2005 ORANGE FOOTBALL GAME #10 • SYRACUSE VS. NOTRE DAME • NOVEMBER 19, 2005 Notre Dame Stadium (80,795) SYRACUSE (1-8 overall, 0-6 BIG EAST) South Bend, Ind. vs. November 19, 2005 2:30 p.m. # 6/7 NOTRE DAME (7-2 overall) NBC On the Air SMITH LEADS NATION IN INTERCEPTIONS Senior safety Anthony SMITH’S 2005 INTERCEPTIONS Television Smith (Hubbard, Ohio) SU’s game versus Notre Dame will be Opponent No. Date took over the national lead Buffalo 2 Sept. 4, 2005 televised live nationally on NBC … Tom in interceptions with a pick Rutgers 2 Oct. 15, 2005 Hammond and Pat Haden call the action. Pittsburgh 1 Oct. 22, 2005 against South Florida in the South Florida 1 Nov. 12, 2005 Radio SU’s last game … He has Syracuse ISP Sports Network Anthony six INT’s and is averaging 0.67 interceptions per game in the Orange’s nine contests… Smith’s INT thwarted The flagship station for the Syracuse ISP Smith a second-quarter drive near midfi eld … He has 14 career interceptions which Sports Network is WAQX-95.7FM … Voice ranks third on SU’s career list … Smith’s six 2005 INTs is the most by an SU defender since Kevin of the Orange Matt Park and analyst Dick Abrams notched six picks in 1995 and his season total is tied with nine other Orange defenders MacPherson will be joined by pre and post-game host and sideline reporter Kevin for the third-most in a single year … If Smith can continue his ball-hawking pace he would Maher … The Syracuse ISP Sports Network be the fi rst Orange player to ever lead the country in interceptions … He leads an Orange can be heared in New York, New Jersey, defense that ranks sixth nationally in pass defense at 163.2 yards per game … Smith also ranks Vermont and Pennsylvania … For a complete seventh nationally in passes defended (1.44 per game), a mark that ranks second in the BIG EAST list of affiliates, please see page 17. -

Student Press in American Archives, Fall/Winter 1973-74. INSTITUTION National Council of Coll

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 035 704 CS 200 797 TITLE Student Press in American Archives, Fall/Winter 1973-74. INSTITUTION National Council of Coll. Publications Advisers, Terre Haute, Ind. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 41p. a AVAILABLE FROM Prof. John Behrens, Curator, Student press in America Archives, Utica College, N. Y. 13502 (Subscriptions $4.00 annually for NCCPA members, $7.00 nonmembers) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Court Cases; Court Litigation; *Journalism; Publications; *School Newspapers; Student Attitudes; Student Opinion; *Student Publications ABSTRACT This issue of the "Student Press in America Archives List" contains 100 entries on current issues and information, as well as cases involving student press editors, advisers, student media, and the generic subject of the campus press, emphasizing censorship practices and principles. Information concerning how and where to obtain documents of relevance on these subjects is listed under each entry. (LL) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION/. WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION I II TI-41% DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DU( ED I xACTIV AS RICE ivED CROY THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION GRIGIN ATING IT POINTS Or VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECFSSARIL Y REFIRE SENT Or t ICI AL NATIONAL INS rIru IC 01 EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Student Lr Press in COWIAmerica Archives Fan/Winter 1973-74 The Student Pressin America Archives is sponsored by National Council of College Publications Advisers. Prof. John Behrens, curator Robert Ryan, editoralassistant. FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY Student Press in America Archives Fall- Winter /1973 I 1. Boston College Refuses to Continue Publication of The Heights, the campus news- paper. -

A Historical Look at the Hill

et al.: A Historical Look at the Hill ~he Hill: An Illustrated Biography of Syracuse University (96 pages, Syracuse University Press, $39.95), author John Robert Greene G'83 notes that it seems "everyone's favorite view of the campus looks high across its panorama, as it sits high upon a hill just to the south of the City of Syracuse." With its diverse architecture-ranging from the majestic Crouse College to the ever-recognizable Carrier Dome-and 130-year history as an institution of Published by SURFACE, 2000 1 Syracuse University Magazine, Vol. 17, Iss. 2 [2000], Art. 9 higher learning, Syracuse University evokes a wealth of memories and images among its students, staff, faculty, alumni, and friends. Greene, author of the last two volumes of SU Press's five-volume history of SU, takes readers on a photo graphic journey through time, capturing the institution's spirit and rich history. What follows is a sampling of the photographs that appear in The Hill, courtesy of Syracuse University Press. https://surface.syr.edu/sumagazine/vol17/iss2/9 2 et al.: A Historical Look at the Hill Yates Castle/Renwick Hall, 1935. The Col lege of Forestry's paper-making machine, billed as the la rgest of its kind at any American college, circa 1952. 30 PublishedS Y by SURFACE,R A C 2000U S E U N V E R S T y M A G A Z N E 3 Syracuse University Magazine, Vol. 17, Iss. 2 [2000], Art. 9 The Hall of Languages, present day; in 1880 (top). -

Varsity Vs. Williams and Mary College in the Stadium

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY 859 Football: 'Varsity vs. Williams and Mary College in the Stadium. Score 61-3 in favor of Syracuse. Also Freshmen vs. Wyoming Seminary, Kingston, Pa. Score 7--0 in favor of the Seminary·. Coach Keane gave his track men a trial over a six mile course. As a result he selected the men to oppose Alfred College next Saturday. Miss Gertrude Williams, '24, Oratory, gave a humerous reading in chapel. Coach Lawrence Lee took the 'Varsity Soccer team to Ithaca for a game with Cornell. Cornell won. The Women's Outing Club hiked to Mausoleum Hill for initiation, camp fires and weiner roast. The College of Forestry will plant trees beside the locks and along the bank of the Barge canal. October 7. Sunday. An Open-house was held from 6 to 7:30 P. M. for students at the Park Central Presbyterian church. The Students' Class at the Fit;st Baptist Church will make a study of the Psalms this year. Miss Pauline Fish, '24, is president of the class and Miss Lillian Smith ,'24, secretary and treasurer. Miss Charlotte Huntoon is the teacher. All Baptist students are urged to attend the meetings of the class. ln the evening the pastor, Dr. Clausen, preached on "A Bid to my Fraternity." A resolution given out by Pi Delta Upsilon, Journalistic fraternity, com mends the benefit to students of work on the various journalistic publications of the University, viz., The Daily Orange, The Onondagan, the Empire Forest er, the Phoenix, the Freshman Handbook and the Camp Log. October 8. -

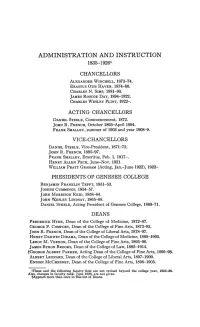

Administration and Instruction 1835-19261

ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION 1835-19261 CHANCELLORS ALEXANDER WINCHELL, 1873-74. ERASTUS OTIS H~VEN, 1874-80. CHARLES N. SIMS, 1881-93. ]AMES RoscoE DAY, 1894-1922. CHARLES WESLEY FLINT, 1922-. ACTING CHANCELLORS DANIEL STEELE, Commencement, 1872. ]OHN R. FRENCH, October 1893-April1894. FRANK SMALLEY, summer of 1903 and year 1908-9. VICE-CHANCELLORS D~NIEL STEELE, Vice-President, 1871-72. ]OHN R. FRENCH, 1895-97. FRANK SMALLEY, Emeritus, Feb. 1, 1917-. HENRY ALLEN PECK, June-Nov. 1921. WILLIAM PR~TT GRAHAM (Acting, Jan.-June 1922), 1922- :PRESIDENTS OF GENESEE COLLEGE BENJAMIN FRANKLIN TEFFT, 1851-53. JosEPH CuMMINGs, 1854-57. JOHN MoRRISON REID, 1858-64. ]OHN WESLEY LINDSAY, 1865-68. DANIEL STEELE, Acting President of Genesee College, 1869-71. DEANS FREDERICK HYDE, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1872-87. GEORGE F. CoMFORT, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1873-93. JOHN R. FRENCH, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1878-97. HE~RY DARWIN DIDAMA, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1888-1905. LEROY M. VERNON, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1893-96. ]AMES BYRON BROOKS, Dean of the College of Law, 1895-1914. tGEORGE ALBERT PARKER, Acting Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1896-98. ALBERT LEONARD, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1897-1900. ENSIGN McCHESNEY, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1898-1905. IThese and the following faculty lists are not revised beyond the college year, 1925-26. Also, changes in faculty rank, June 1926, are not given. tAppears more than once in this list of Deans. ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION-DEANS Io69 FRANK SMALLEY, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts (Acting, Sept.