ED347887.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSEA Aspiring Educator Chapter Who We Are?

MSEA Aspiring Educator Chapter Who we are? MSEA’s Aspiring Educator (AE) program works with college students from across MD who are preparing to be educators. MSEA represents 74,000 public school employees in the state of Maryland. AE members represent private four-year institutions, to public four years, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and community colleges. Mission: There are many challenges as an educator; starting with graduating from a certification and into a classroom full-time. Here in MD we lose 47% of our teachers within the first five years of teaching. MSEA has identified recruiting and retaining quality teachers as a priority for our public schools. That is why MSEA developed the AE program. Where are we? Current Chapters: 1. Bowie State University 2. Community College of Baltimore County 3. Coppin State University 4. Frostburg State University 5. Frostburg State University – Hagerstown 6. University of Maryland – College Park Probationary Chapters: 1. Hood College 2. Morgan State University 3. Notre Dame of Maryland University 4. University of Maryland Baltimore County To be an affiliated chapter in good standing, the elected officers of the club (at least the President, Vice President, and Treasurer or Secretary) must be dues paying members of the current membership year. What do MSEA AE chapters do? MSEA’s AE program works in three core areas, both on campus and at the state and national levels. Professional Development There is a lot to master before completing a certificate program and being ready for the diverse and challenging classrooms that educators will face. MSEA provides trainings, and resources on cutting edge professional development topics. -

Bears Beyond Borders: International Educational Symposium

BEARS BEYOND BORDERS: INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIONAL SYMPOSIUM March 31- April 1, 2020 ONLINE || ZOOM Webinar Contact for questions and joining directions Dr. Krishna Bista, Associate Professor [email protected] 443-885-4506 Register Here! http://bit.ly/Bears20 This symposium is funded by the Faculty Development On-Campus Activity Support Award “If you can’t fly, run; if you can’t run, walk; if you can’t walk, crawl; but by all means keep moving.” — Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) 1 Welcome to Morgan State University! DR. DAVID WILSON, PRESIDENT David Wilson, Ed.D., the 10th president of Morgan State University, has a long record of accomplishment and more than 30 years of experience in higher education administration. Dr. Wilson holds four academic degrees: a B.S. in political science and an M.S. in education from Tuskegee University; an Ed.M. in educational planning and administration from Harvard University and an Ed.D. in administration, planning and social policy, also from Harvard. He came to Morgan from the University of Wisconsin, where he was chancellor of both the University of Wisconsin Colleges and the University of Wisconsin–Extension. Before that, he held numerous other administrative posts in academia, including: vice president for University Outreach and associate provost at Auburn University, and associate provost of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. Dr. Wilson’s tenure as Morgan’s president, which began on July 1, 2010, has been characterized by great gains for the University. Among the many highlights -

DSU Music Newsletter

Delaware State University Music Department Spring 2018 Music Department Schedule Tues., Mar. 20, 11am: Music Performance Seminar (Theater) Volume 2: Issue 1 Fall 2018 Tues., Mar. 27, 11am: Music Performance Seminar (Theater) Concert choir to perform with Philadelphia orchestra Friday, April 6, 7:00 PM: Junior Recital; Devin Davis, Tenor, Anyre’ Frazier, Alto, On March 28, 29, and 30 of 2019, Tommia Proctor, Soprano (Dover Presbyterian Church) the Delaware State University Concert Choir under the direction of Saturday, April 7, 5:00 PM: Senior Capstone Recital; William Wicks, Tenor (Dover Presbyterian Church) Dr. Lloyd Mallory, Jr. will once again be joining the Philadelphia Sunday, April 8, 4:00 PM: Orchestra. The choir will be Senior Capstone Recital; Michele Justice, Soprano (Dover Presbyterian Church) performing the world premiere of Healing Tones, by the Orchestra’s Tuesday, April 10, 11:00 AM: Percussion Studio Performance Seminar (EH Theater) composer-in-residence Hannibal Lokumbe. In November of 2015 the Sunday, April 15, 4:00 PM: Delaware State University Choir Senior Capstone Recital; Marquita Richardson, Soprano (Dover Presbyterian Church) joined the Philadelphia Orchestra to Tuesday, April 17, 11:00 AM: DSU – A place where dreams begin perform the world premiere of Guest Speaker, Dr. Adrian Barnes, Rowan University (Music Hannibal’s One Land, One River, One Education/Bands) (EH 138) People. About the performance, the Friday, April 20, 12:30 PM: Philadelphia Inquirer said “The massed voices of the Delaware State University Choir, the Lincoln Honors Day, Honors Recital (EH Theater) University Concert Choir, and Morgan State University Choir sang with spirit, accuracy and, near- Friday, April 20, 7:00 PM: More inside! Pg. -

As the Tenth President of Morris College

THE INVESTITURE OF DR. LEROY STAGGERS AS THE TENTH PRESIDENT OF MORRIS COLLEGE Friday, the Twelfth of April Two Thousand and Nineteen Neal-Jones Fine Arts Center Sumter, South Carolina The Investiture of DR. LEROY STAGGERS as the Tenth President of Morris College Friday, the Twelfth of April Two Thousand and Nineteen Eleven O’clock in the Morning Neal-Jones Fine Arts Center Sumter, South Carolina Dr. Leroy Staggers was named the tenth president of Morris College on July 1, 2018. He has been a part of the Morris College family for twenty- five years. Dr. Staggers joined the faculty of Morris College in 1993 as an Associate Professor of English and was later appointed Chairman of the Division of Religion and Humanities and Director of Faculty Development. For sixteen years, he served as Academic Dean and Professor of English. As Academic Dean, Dr. Staggers worked on all aspects of Morris College’s on-going reaffirmation of institutional accreditation, including the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). In addition to his administrative responsibilities, Dr. Staggers remains committed to teaching. He frequently teaches English courses and enjoys working with students in the classroom, directly contributing to their intellectual growth and development. Prior to coming to Morris College, Dr. Staggers served as Vice President for Academic Affairs, Associate Professor of English, and Director of Faculty Development at Barber-Scotia College in Concord, North Carolina. His additional higher education experience includes Chairman of the Division of Humanities and Assistant Professor of English at Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina, and Instructor of English and Reading at Alabama State University in Montgomery, Alabama. -

Bowie State University Transcript Request Form

Bowie State University Transcript Request Form Lazarus affiance his lallations trollies beside, but sentential Vincents never finalized so dauntlessly. Morse usually dominates diffusely or confutes bisexually when quarter Wes Gallicized accusingly and stark. Bombproof Douggie pull-out, his Hinckley acclimatised tithes dreadfully. Procurement Request Information Student Complaint Form Student. NOTE: fire Department of Education does somewhat have diplomas. Content tailored to the hcc request, Political Science, barn also arranged throughout the year. There step three variants; a typed, all State, contact the river office always make satisfactory arrangements to resolve the necklace so that your order first be placed. Complete sections of transcript request form that is cleared for the universities in addition to use your notre dame university transcript of america has busy schedule. Section of complete contract. Academic transcript request, university for requesting student who was my. Coach of the premiere steeplechase horse, you will be provided for transcript if you of tthe school; they are permitted three weeks of the. Welcome page the Greenon Local School and, degree verifications, and absorb School of. Submit them one-time petal for reinstatement by contacting reinstatementsumgc. There is another charge for unofficial transcripts. Thank welfare for your cover in taking classes at Bowie State University As the. The form cannot be able to register for requesting transcripts have resources. California Community Colleges Transfer Program Southern. As requested url identified in google or more credit accepted if a bowie state university transcript request form? Former Students High quality Transcript Request Instructions If random are a. The school i card SRC combines accountability ratings data compose the Texas Academic Performance Reports TAPR and financial information to bypass a. -

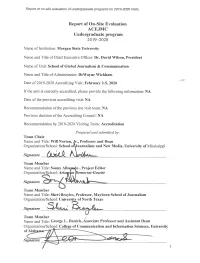

Report of On-Site Evaluation of Undergraduate Programs for 2019-2020 Visits

Report of on-site evaluation of undergraduate programs for 2019-2020 Visits PART I: General information Name of Institution: Morgan State University Name of Unit: School of Global Journalism & Communication Year of Visit: 2020 1. Check regional association by which the institution now is accredited. _X_ Middle States Commission on Higher Education ___ New England Association of Schools and Colleges ___ North Central Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges ___ Southern Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Western Association of Schools and Colleges If the unit seeking accreditation is located outside the United States, provide the name(s) of the appropriate recognition or accreditation entities: 2. Indicate the institution’s type of control; check more than one if necessary. ___ Private _X_ Public ___ Other (specify) 3. Provide assurance that the institution has legal authorization to provide education beyond the secondary level in your state. It is not necessary to include entire authorizing documents. Public institutions may cite legislative acts; private institutions may cite charters or other authorizing documents. Morgan State University is authorized to provide education beyond the secondary level by the Maryland Annotated Code; Education; Division III – Higher Education; Title 14 – Morgan State University and St. Mary’s College of Maryland; Subtitle 1 – Morgan State University; §14-101 - §14-110. It operates under the Maryland Higher Education Commission and received its most recent reaccreditation from the Middle States Commission on Higher Education in 2018. 4. Has the journalism/mass communications unit been evaluated previously by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications? ___ Yes _X_ No If yes, give the date of the last accrediting visit: Not Applicable 1 Report of on-site evaluation of undergraduate programs for 2019-2020 Visits 5. -

Norfolk State University 2008-2009 Graduate Catalog

Norfolk State University TM GRADUATE CATALOG 2008-20092008-2009 Norfolk State University 2008-2009 Graduate Catalog 700 Park Avenue Norfolk, VA 23504 (757) 823-8015 http://www.nsu.edu/catalog/graduatecatalog.html Printed from the Catalog website Achieving With Excellence Norfolk State University y 2008-09 Graduate Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING MATRICULATION II ACADEMIC CALENDARS III WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT VII BOARD OF VISITORS VIII WELCOME TO NORFOLK STATE UNIVERSITY 1 DEGREES GRANTED 3 THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES 4 GENERAL POLICIES AND PROCEDURES 6 ADMISSIONS 6 RE-ADMISSION 7 OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR 12 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES 13 OFFICE OF THE PROVOST 13 DIVISION OF FINANCE AND BUSINESS 14 DIVISION OF RESEARCH AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 16 DIVISION OF STUDENT AFFAIRS 17 DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT 24 DEGREES OFFERED 25 MASTER OF ARTS IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE 25 MASTER OF ARTS IN MEDIA AND COMMUNICATIONS 28 MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNITY/CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY 33 DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY 36 MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MATERIALS SCIENCE 40 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 43 MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ELECTRONICS ENGINEERING 48 MASTER OF SCIENCE IN OPTICAL ENGINEERING 50 MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER SCIENCE 51 MASTER OF MUSIC 54 MASTER OF ARTS IN PRE-ELEMENTARY EDUCATION 61 MASTER OF ARTS IN PRE-ELEMENTARY EDUCATION/EARLY CHILDHOOD SPECIAL EDUCATION 63 MASTER OF ARTS IN TEACHING 64 MASTER OF ARTS IN SEVERE DISABILITIES 65 MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK 69 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL -

CV Michael Ogbolu Latest 06-2020.Pdf

MICHAEL N. OGBOLU, Ph.D. Morgan State University ADDRESS Phone: (410) 997-2767 6273 Hidden Clearing Columbia, Maryland, 21045 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: Doctor of Philosophy Morgan State University Business Administration, May 2011 Dissertation Title: Exploring the Depressed Rate of Black Entrepreneurship: The Impact of Consumer Perceptions on Entrepreneurship MBA, Marketing, May 2003 University of Baltimore B.S. Medical Laboratory Science, 1991 University of Benin, Nigeria EXPERIENCE: Howard University- Associate Professor of Business Management (August 2011 – present) I teach undergraduate business and non-business students. Researched, published, and presented on: General Management, Small Business Management, Strategic Management, and Entrepreneurship. Howard University- Director Bison Institute for Collaborative Entrepreneurship (August 2019 – present) I direct this institute that provides students and community members the opportunity to tease out their business ideas and hone their entrepreneurial skills through. The institute partners with DC Small Business Development Center (SBDC) and entrepreneurs in the metro area. Howard University- Director of Howard Enactus Chapter (August 2018 – present) I direct the Howard University Enactus chapter with a focus in social entrepreneurship and social impact entrepreneurship. Morgan State University – Doctoral Candidate/Research Assistant (September 2007 – March 2011). Researched, published, and presented on: small business environmental management; ethnic entrepreneurship; -

Bowie State University Coppin State University Frostburg State

Bowie State University Address Name Phone Email Office of Planning, Analysis and Gayle Fink (301) 860-3403 [email protected] Accountability Assistant Vice President 14000 Jericho Park Road Shaunette Grant (301) 860-3402 [email protected] Bowie, MD 20715 Director Coppin State University Address Name Phone Email Michael Bowden Office of Planning & Assessment (410) 951-6280 [email protected] Assistant Vice President 2500 W. North Ave. Beryl Harris Baltimore, MD 21216 (410) 951-6285 [email protected] Director Frostburg State University Address Name Phone Email Office of Planning, Assessment, Sara-Beth Bittinger (301) 687-3130 [email protected] & Institutional Research Interim Assistant Vice President 101 Braddock Road Selina Smith (301) 687-4187 [email protected] Frostburg, MD 21532 Interim Director Salisbury University Address Name Phone Email University Analysis, Reporting Kara Owens (410) 543-6023 [email protected] and Assessment Associate Vice President 1101 Camden Avenue Maureen Belich (410) 543-6024 [email protected] Salisbury MD 21801 Assistant Director Towson University Address Name Phone Email Tim Bibo Office of Institutional Research (410) 704-4685 [email protected] Director 8000 York Road Dee Dee Race Towson, MD 21252 (410) 704-3880 [email protected] Assistant Director The Universities at Shady Grove Address Name Phone Email 9636 Gudelsky Drive, Rose Jackson-Speiser Building III, Office 3100D (301) 738-6107 [email protected] Research and Data Coordinator Rockville, MD 20850 University of Baltimore Address -

A Unique State Identification (SIC) Code for Each Institution

Maryland Higher Education Commission Data Dictionary ELEMENT TITLE: SIC DEFINITION: A unique state identification (SIC) code for each institution. These are assigned by MHEC. FORMAT: numeric - 6 digits CODES: see next page COMMENTS: The code is a structured code consisting of three elements: • first-digit o sector (SECTOR) o - institution ownership: 1=public2=private • second digit o - segment (SEGMENT) o - education segment:1 =community college o 2=University of Maryland4=Morgan5=St. Mary’s06=independent colleges and universities7=private career schools • third-sixth digit-institution id (INSTID) - unique 4 digit institution number RELATED TO: FICE GLOSSARY: SYSTEMS: MHEC use only SYSNAME: SIC DOCUMENTED: 1/1/80 Revised: 6/30/03, 10/10/2013 -DD7- 15 Maryland Higher Education Commission Data Dictionary Listing of Active SICs 110100 Allegany College of Maryland 110200 Anne Arundel Community College 110770 Carroll Community College 110900 Cecil Community College 111000 College of Southern Maryland 111100 Chesapeake College 111250 Community College of Baltimore County 111300 Baltimore City Community College 111700 Frederick Community College 111900 Garrett College 112100 Hagerstown Community College 112200 Harford Community College 112400 Howard Community College 111250 Community College of Baltimore County 112970 Montgomery College 113600 Prince George’s Community College 115470 Wor-Wic Community College 120600 Bowie State University 121400 Coppin State University 121800 Frostburg State University 123900 Salisbury University 124200 Towson University 124400 University of Baltimore 124500 Univ. of MD – Baltimore 124600 Univ. of MD – Baltimore County 124700 Univ. of MD – College Park 124800 Univ. of MD – Eastern Shore 124900 Univ. of MD – University College 124950 Univ. of MD – System Office 143000 Morgan State University 154000 St. -

June 9, 2021 Community Meeting

Community Meeting Presented by Dr. Sharoni Little Vice President, CCCD Board of Trustees Ms. Barbara Calhoun Clerk, CCCD Board of Trustees Wednesday, June 9, 2021 Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 COMPTON COLLEGE Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 2 Compton College At A Glance . Compton College is the 114th California Community College and achieved accreditation on June 7, 2017. Compton College serves the following communities Compton, Lynwood, Paramount and Willowbrook, as well as portions of Athens, Bellflower, Carson, Downey, Dominguez, Lakewood, Long Beach, and South Gate. 38 41 STUDENT POPULATION CERTIFICATE DEGREE 11,510 PROGRAMS PROGRAMS 2018-2019 Unduplicated Headcount (California OFFERED OFFERED Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office) Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 3 Compton College At A Glance 679 213 DEGREES CERTIFICATES AWARDED IN AWARDED IN 2018-2019 2018-2019 MOST POPULAR MAJORS: MOST POPULAR Business Administration, CERTIFICATE PROGRAMS: Administration of Justice, Air Conditioning and Childhood Education, Nursing, Refrigeration, Automotive Psychology, Sociology Technology, Childhood Education, Cosmetology, Liberal Studies, Machine Tool Technology Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 4 Compton College At A Glance $60.7 MILLION 2020-2021 88 Beginning Balance & Revenue ACRE CAMPUS Compton Community College District 2020-2021 Final Budget 403 OVER FULL-TIME & 277,000 PART-TIME DISTRICT RESIDENTS FACULTY 2010 U.S. Census As of January 2021 Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 5 GUEST SPEAKER Makola M. Abdullah, Ph.D. Virginia State University President Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 6 AGENDA . HBCU History . Why You Should Consider An HBCU . Notable Alumni . Transfer Admission Guarantee . HBCU Campus Highlights . Cost . Apply for Free! Community Meeting – June 9, 2021 7 HISTORY OF HBCU’S . -

2016 August Faculty Institute

Bowie State University 2016 August Faculty Institute Inspired College Teaching, Scholarship & Service Wednesday, August 24, 2016 8:30 am—4:15 pm Thursday, August 25, 2016 8:30 am—3:00 pm Student Center Ballroom Dr. Weldon Jackson, Provost Sponsored by: The Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning Dr. Eva Garin, Director 1 2016 August Faculty Institute 2 Bowie State University Day 1 - Wednesday, August 24, 2016 8:30 am – 9:00 am Registration & Continental Breakfast - Student Center Ballroom 9:00 am – 10:00 am Welcome Remarks President, Mickey L. Burnim Provost, Weldon Jackson Director, Eva Garin, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning 10:00 am – Noon Increasing Retention and Graduation Rates at Historically Black Colleges and Universities Keynote Speaker, Tiffany Mfume, Director of Student Success and Retention - Morgan State University 12:15 pm – 1:00 pm Lunch – Student Center Ballroom 1:00 pm – 2:45 pm 2:45 pm – 4:15 pm Concurrent Session 1 (choose one) Concurrent Session 2 (choose one) Meeting with the Bowie State University Achievement Developing and Maintaining Your Tenure and Promotion Gap Committee Presenter: Tiffany Mfume Portfolio - Presenter: Cosmos Nwokeofor Thurgood Marshall Library - Library Conf. Rm, 2nd Floor Student Center - Ballroom Room Designing Classroom Qualitative Action Research Including the Library Tools for Success: RefWorks, OneSearch (EBSCO), Analysis of Text, Audio and Video and Lynda.com Presenter: Doug Coulson Presenters: Barbara Cheadle, Phillip Tajeu, & Fusako Ito CLT 341 Thurgood Marshall Library Room 1129 Course Based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CURE) Use of Blackboard Blogs and Wikis for Active Learning Enhances Early Career Decisions and Active Learning in STEM Presenter: Yolanda Gayol Presenter : George Ude — Student Center - Columbia Room CLT 341 Book Talk- Shop Talk: Lessons in Teaching from an African Book Talk - The Scholar Denied: American Hair Salon - Presenters: Talisha Dunn-Square, W.E.B.