1 the Phonetics of Sokuon, Or Geminate Obstruents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 10:48:31PM Via Free Access

journal of language contact 11 (2018) 71-112 brill.com/jlc The Development of Phonological Stratification: Evidence from Stop Voicing Perception in Gurindji Kriol and Roper Kriol Jesse Stewart University of Saskatchewan [email protected] Felicity Meakins University of Queensland [email protected] Cassandra Algy Karungkarni Arts [email protected] Angelina Joshua Ngukurr Language Centre [email protected] Abstract This study tests the effect of multilingualism and language contact on consonant perception. Here, we explore the emergence of phonological stratification using two alternative forced-choice (2afc) identification task experiments to test listener perception of stop voicing with contrasting minimal pairs modified along a 10-step continuum. We examine a unique language ecology consisting of three languages spo- ken in Northern Territory, Australia: Roper Kriol (an English-lexifier creole language), Gurindji (Pama-Nyungan), and Gurindji Kriol (a mixed language derived from Gurindji and Kriol). In addition, this study focuses on three distinct age groups: children (group i, 8>), preteens to middle-aged adults (group ii, 10–58), and older adults (group iii, 65+). Results reveal that both Kriol and Gurindji Kriol listeners in group ii contrast the labial series [p] and [b]. Contrarily, while alveolar [t] and velar [k] were consis- tently identifiable by the majority of participants (74%), their voiced counterparts ([d] and [g]) showed random response patterns by 61% of the participants. Responses © Jesse Stewart et al., 2018 | doi 10.1163/19552629-01101003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication. -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

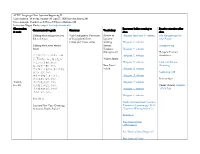

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

Android Apps for Learning Kana Recommended by Our Students

Android Apps for learning Kana recommended by our students [Kana column: H = Hiragana, K = Katakana] Below are some recommendations for Kana learning apps, ranked in descending order by our students. Please try a few of these and find one that suits your needs. Enjoy learning Kana! Recommended Points App Name Kana Language Description Link Listening Writing Quizzes English: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/jpn/id739.html English, Developed by the Japan Foundation and uses Hiragana Memory Hint H Indonesian, 〇 〇 picture mnemonics to help you memorize Indonesian: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id746.html Thai Hiragana. Thai: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id773.html English: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id743.html English, Developed by the Japan Foundation and uses Katakana Memory Hint K Indonesian, 〇 〇 picture mnemonics to help you memorize Indonesian: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id747.html Thai Katakana. Thai: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id775.html A holistic app that can be used to master Kana Obenkyo H&K English 〇 〇 fully, and eventually also for other skills like https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id602.html Kanji and grammar. A very integrated quizzing system with five Kana (Hiragana and Katakana) H&K English 〇 〇 https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/jpn/id626.html varieties of tests available. Uses SRS (Spatial Repetition System) to help Kana Town H&K English 〇 〇 https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id845.html build memory. Although the app is entirely in Japanese, it only has Hiragana and Katakana so the interface Free Learn Japanese Hiragana H&K Japanese 〇 〇 〇 does not pose a problem as such. -

Machine Transliteration (Knight & Graehl, ACL

Machine Transliteration (Knight & Graehl, ACL 97) Kevin Duh UW Machine Translation Reading Group, 11/30/2005 Transliteration & Back-transliteration • Transliteration: • Translating proper names, technical terms, etc. based on phonetic equivalents • Complicated for language pairs with different alphabets & sound inventories • E.g. “computer” --> “konpyuutaa” 䜷䝷䝗䝩䜪䝃䞀 • Back-transliteration • E.g. “konpyuuta” --> “computer” • Inversion of a lossy process Japanese/English Examples • Some notes about Japanese: • Katakana phonetic system for foreign names/loan words • Syllabary writing: • e.g. one symbol for “ga”䚭䜰, one for “gi”䚭䜲 • Consonant-vowel (CV) structure • Less distinction of L/R and H/F sounds • Examples: • Golfbag --> goruhubaggu 䜸䝯䝙䝔䝇䜴 • New York Times --> nyuuyooku taimuzu䚭䝏䝩䞀䝬䞀䜳䚭䝃䜨䝤䜾 • Ice cream --> aisukuriimu 䜦䜨䜽䜳䝮䞀䝤 The Challenge of Machine Back-transliteration • Back-transliteration is an important component for MT systems • For J/E: Katakana phrases are the largest source of phrases that do not appear in bilingual dictionary or training corpora • Claims: • Back-transliteration is less forgiving than transliteration • Back-transliteration is harder than romanization • For J/E, not all katakana phrases can be “sounded out” by back-transliteration • word processing --> waapuro • personal computer --> pasokon Modular WSA and WFSTs • P(w) - generates English words • P(e|w) - English words to English pronounciation • P(j|e) - English to Japanese sound conversion • P(k|j) - Japanese sound to katakana • P(o|k) - katakana to OCR • Given a katana string observed by OCR, find the English word sequence w that maximizes !!!P(w)P(e | w)P( j | e)P(k | j)P(o | k) e j k Two Potential Solutions • Learn from bilingual dictionaries, then generalize • Pro: Simple supervised learning problem • Con: finding direct correspondence between English alphabets and Japanese katakana may be too tenuous • Build a generative model of transliteration, then invert (Knight & Graehl’s approach): 1. -

Trubetzkoy Final

Chapman, S. & Routledge, P. (eds) (2005) Key Thinkers in Linguistics and the Philosophy of Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Pp 267-268. Trubetzkoy, N.S. (Nikolai Sergeevich); (b. 1890, d. 1938; Russian), lecturer at Moscow University (1915-1916), Rostov-on-Don University (1918), Sofia University (1920-1922), finally professor of Slavic linguistics at Vienna University (1922-1938). One of the founding fathers of phonology and a key theorist of the Prague School. (See Also: *Jakobson, Roman; *Martinet, André). Trubetzkoy’s life was blighted by persecution. Born in Moscow of aristocratic, academic parents, Trubetzkoy (whose names have been transliterated variously) was a prince, and, after study and an immediate start to a university career in Moscow, he was forced to flee by the 1917 revolution; he subsequently also had to leave Rostov and Sofia. On settling in Vienna, he became a geographically distant member of the Prague Linguistic Circle. It is at times difficult to tease his ideas apart from those of his friend *Jakobson, who ensured that his nearly-finished Grundzüge der Phonologie (1939) was posthumously published. Trubetzkoy had previously published substantial work in several fields, but this was his magnum opus. It summarised his previous phonological work and stands now as the classic statement of Prague School phonology, setting out an array of phonological ideas, several of which still characterise debate on phonological representations. Through it, the publications which preceded it, his work at conferences and general enthusiastic networking, Trubetzkoy was crucial in the development of phonology as a discipline distinct from phonetics, and the change in phonological focus from diachrony to synchrony. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

KANA Response Live Organization Administration Tool Guide

This is the most recent version of this document provided by KANA Software, Inc. to Genesys, for the version of the KANA software products licensed for use with the Genesys eServices (Multimedia) products. Click here to access this document. KANA Response Live Organization Administration KANA Response Live Version 10 R2 February 2008 KANA Response Live Organization Administration All contents of this documentation are the property of KANA Software, Inc. (“KANA”) (and if relevant its third party licensors) and protected by United States and international copyright laws. All Rights Reserved. © 2008 KANA Software, Inc. Terms of Use: This software and documentation are provided solely pursuant to the terms of a license agreement between the user and KANA (the “Agreement”) and any use in violation of, or not pursuant to any such Agreement shall be deemed copyright infringement and a violation of KANA's rights in the software and documentation and the user consents to KANA's obtaining of injunctive relief precluding any further such use. KANA assumes no responsibility for any damage that may occur either directly or indirectly, or any consequential damages that may result from the use of this documentation or any KANA software product except as expressly provided in the Agreement, any use hereunder is on an as-is basis, without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement. Use, duplication, or disclosure by licensee of any materials provided by KANA is subject to restrictions as set forth in the Agreement. Information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of KANA. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role.