Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 10 Aboriginal Children's Books for Victoria

the importance of understanding where we with her dingos, looking for grubs and berries. come from and how to relate to the land and She walked for a long time dragging a digging Top 10 Aboriginal children’s water surrounding us all. Woiwurrung words, stick behind her, which made a track along the such as ‘wominjeka’, are introduced through the ground. The sound of the stick woke the snake, VWRU\DQGZHDUHRʏHUHGDQLQVLJKWLQWRKRZ and he became very angry and thrashed to and books for Victoria Aboriginal communities relate to one another fro, causing the track to get bigger. Soon after, through acknowledging territorial boundaries, it rained and this was how the Murray River was seeking permission to enter other lands and made. This is an engaging and interesting way performing Welcomes to Country. A video of for educators and teachers to introduce the Here are our top 10 children’s books written by Aunty Joy reading her book can be viewed at: topic of belief systems. Victorian Aboriginal people who feel a sense of http://bit.ly/WelcomeToCountryBook 8. Respect 5. Took the belonging to their nations, clans, land and culture. $XQW\)D\H0XLU6XH/DZVRQ Children Away /LVD.HQQHG\ LOOXVWUDWRU Archie Roach / Ruby Hunter Aunty Fay is a Boon Wurrung (illustrator) with paintings by and Wamba Wamba Elder MATILDA DARVALL, Senior Policy Officer & Peter Hudson MERLE HALL, Koorie Inclusion Consultant, ZKRZURWHWKLVERRNZLWK6XH/DZVRQDQ Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Took the Children Away is a story written award-winning children’s author. This book Incorporated (VAEAI) by well-known singer Archie Roach, and teaches us how to respect our Elders, our illustrated by his late partner Ruby Hunter. -

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

19 Language Revitalisation: Community and School Programs Working Together

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 19 Language revitalisation: community and school programs working together Diane McNaboe1 and Susan Poetsch2 Abstract Since it was published in 2003 the New South Wales Aboriginal Languages K– 10 Syllabus has led to a substantial increase in the number of school programs operating in the state. It has supported the quality of those programs, and the status and recognition given to Aboriginal languages and cultures in the curriculum. School programs also complement community initiatives to revitalise, strengthen and share Aboriginal languages in New South Wales. As linguistic and cultural knowledge increases among adult community members, school programs provide a channel for them to continue to develop their own skills and knowledge and to pass on this heritage. This paper takes Wiradjuri as an example of language revitalisation, and describes achievements in adult language learning and the process of developing a school program with strong input from community. A brief history of Wiradjuri language revitalisation Wiradjuri is one of the central inland New South Wales (NSW) languages (Wafer & Lissarrague 2008, pp. 215–25). In recent decades various language teams have investigated and analysed archival sources for Wiradjuri and collected information from both written and oral sources (Büchli 2006, pp. 58–60). These teams include Grant and Rudder (2001a, b, c, d; 2005), Hosking and McNicol (1993), McNicol and Hosking (1994) and Donaldson (1984), as well as Christopher Kirkbright, George Fisher and Cheryl Riley, who have been working with Wiradjuri people in and near Sydney. -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Luise A. Hercus, 1963-1965

Finding aid HERCUS_L08 Sound recordings collected by Luise A. Hercus, 1963-1965 Prepared January 2014 by SL Last updated 30 November 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained permission from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. This collection may only be copied with the permission of Luise Hercus or her representatives. Permission must be sought from Luise Hercus or her representatives as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 16 sound tape reels (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, 3 3/4, 7 1/2 ips, mono. ; 5 in. + field tape report sheets Production history These recordings were collected between 1963 and 1965 by linguist Luise Hercus during field trips to Point Pearce, South Australia, Framlingham, Lake Condah, Drouin, Jindivick, Fitzroy, Strathmerton, Echuca, Antwerp and Swan Hill in Victoria, and Dareton, Curlwaa, Wilcannia, Hay, Balranald, Deniliquin and Quaama in New South Wales. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages and songs of the Madhi Madhi, Parnkalla, Kurnai, Gunditjmara, Yorta Yorta, Paakantyi, Ngarigo, Wemba Wemba and Wergaia peoples. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

MATHEWS J16 Sound Recordings Collected by Janet Mathews, 1972

Finding aid MATHEWS_J16 Sound recordings collected by Janet Mathews, 1972 Prepared November, 2006 by MH Last updated 12 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact AIATSIS to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use This collection is open for copying to the people recorded on the tapes, their relatives, Aboriginal communities in and around the places where the tapes were recorded, speakers of the languages recorded on the tapes, and Aboriginal cultural centres in and around the places where the tapes were recorded. All other clients may only copy this collection with the permission of Susan Upton. Permission must be sought from Susan Upton and the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1972 Extent: 18 sound tape reels (ca. 1 hr. each) : analogue, 3 ¾ ips, mono + field tape report sheets Production history These recordings were collected by Janet Mathews between the 10th and 16th of April 1972 in Coonamble, Lightning Ridge, Weilmoringle and Brewarrina. They document various languages spoken in western New South Wales, including Wailwan, Yuwaalaraay, Guwamu and Muruwari, as spoken by Bill Davis, Fred Reece, Robin Campbell and Daisy Brown. The recordings also feature an oral history interview in English with Jimmie Barker. RELATED MATERIAL John Giacon has prepared partial transcripts of field tapes 104 - 112, copies of which are held by the AIATSIS Audiovisual Archive. For a complete listing of related material held by AIATSIS, consult the Institute's Mura® online catalogue at http://mura.aiatsis.gov.au. -

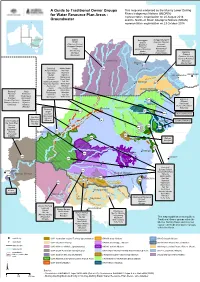

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

Aboriginal Languages

Aboriginal Languages Advice on Programming and Assessment for Stages 4 and 5 Acknowledgements The map on p 8 is © Department of Lands, Panorama Ave, Bathurst, NSW, www.lands.nsw.gov.au © 2003 Copyright Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales. This document contains Material prepared by the Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales. The Material is protected by Crown copyright. All rights reserved. No part of the Material may be reproduced in Australia or in any other country by any process, electronic or otherwise, in any material form or transmitted to any other person or stored electronically in any form without the prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW, except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968. School students in NSW and teachers in schools in NSW may copy reasonable portions of the Material for the purposes of bona fide research or study. When you access the Material you agree: • to use the Material for information purposes only • to reproduce a single copy for personal bona fide study use only and not to reproduce any major extract or the entire Material without the prior permission of the Board of Studies NSW • to acknowledge that the Material is provided by the Board of Studies NSW • not to make any charge for providing the Material or any part of the Material to another person or in any way make commercial use of the Material without the prior written consent of the Board of Studies NSW and payment of the appropriate copyright fee • to include this copyright notice in any copy made • not to modify the Material or any part of the material without the express prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW. -

Noun Phrase Constituency in Australian Languages: a Typological Study

Linguistic Typology 2016; 20(1): 25–80 Dana Louagie and Jean-Christophe Verstraete Noun phrase constituency in Australian languages: A typological study DOI 10.1515/lingty-2016-0002 Received July 14, 2015; revised December 17, 2015 Abstract: This article examines whether Australian languages generally lack clear noun phrase structures, as has sometimes been argued in the literature. We break up the notion of NP constituency into a set of concrete typological parameters, and analyse these across a sample of 100 languages, representing a significant portion of diversity on the Australian continent. We show that there is little evidence to support general ideas about the absence of NP structures, and we argue that it makes more sense to typologize languages on the basis of where and how they allow “classic” NP construal, and how this fits into the broader range of construals in the nominal domain. Keywords: Australian languages, constituency, discontinuous constituents, non- configurationality, noun phrase, phrase-marking, phrasehood, syntax, word- marking, word order 1 Introduction It has often been argued that Australian languages show unusual syntactic flexibility in the nominal domain, and may even lack clear noun phrase struc- tures altogether – e. g., in Blake (1983), Heath (1986), Harvey (2001: 112), Evans (2003a: 227–233), Campbell (2006: 57); see also McGregor (1997: 84), Cutfield (2011: 46–50), Nordlinger (2014: 237–241) for overviews and more general dis- cussion of claims to this effect. This idea is based mainly on features -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc.