BOOKBINDING .;'Ft1'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incorporating Indigenous Knowledge in the Care of Threatened Species at Arakwal National Park

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge in the care of threatened species at Arakwal National Park Project 6.2.1 KEY MESSAGES • Scientists, Traditional • We have held planning • Over the past year, this Owners and Park staff and evaluation workshops project has supported are working together to to develop knowledge- a back-to-country manage the Byron Bay sharing protocols, priority workshop for local Orchid (Diuris byronensis) actions and measures Indigenous families, and its clay heath habitat of success to care for cultural burning in Arakwal National Park. these important areas. on the clay heath habitat and community engagement activities. What is the problem being tackled? The endangered Byron Bay Orchid (Diuris byronensis) is unique to Arakwal National Park. The orchid and its endangered clay heath habitat, which is an endangered ecological community, have important conservation and cultural values. Yet these values are threatened by wild fires, weeds, feral animals and the impact of thousands of tourists who visit this region throughout the year. Joint managers at Arakwal need to work together to ensure effective joint management of these important species and areas. Indigenous burning of clay heath was recently carried out for the first time in 30 years. Photo: Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation. Who is involved? Why is this important to the Bundjalung of Byron Bay People (Arakwal)? This project is a collaboration Local Traditional Owners are the Bundjalung of Byron Bay between Bundjalung people interested in the decisions and People (Arakwal) to look after of Byron Bay (Arakwal), outcomes achieved in this the things they think are most Arakwal joint Park Managers, protected area. -

March/April 2016

www.kyogle.nsw.gov.au Kyogle Council Community Newsletter MARCH/APRIL 2016 Kyogle Council Working together to balance Environment, Lifestyle and Opportunity. NEW LIBRARY In this MAYORAL FOWL MYTH BRIDGE LIBRARY ON ISSUE MESSAGE CONCERNS BUSTERS OPENED NEWS WHEELS 2 2 3 4 7 8 $3 million packing plant APPROVED Kyogle Council has unanimously ap- proved a development application from Mountain Blue Farms for a $3 million blueberry packing plant at Tabulam. The packing plant will be located on Tabulam Road directly across the Clarence River from Mountain Blue Farms’ existing blueberry farm. When built, the packing plant is ex- A $3 million blueberry packing plant approved for development at Tabulam is expected to create 22 pected to create 22 permanent jobs on top permanent jobs. of the 500 plus seasonal workers that the farm is likely to employ to harvest the development control issues could be ap- Council would receive significant Section blueberries each year. propriately addressed and to get this im- 94 Developer Contributions as well as Many of the seasonal workers are likely portant industry activated in our local area. additional works from the applicant to- to be backpackers who will stay locally "This has included holding talks with wards road upgrades along Tabulam Road and further boost the local economy. members of the local community about as part of the consent conditions for the "Blueberries not only help showcase the opportunities for providing additional ac- packing plant. area's agricultural diversity but also have commodation for workers.” “This is expected to make the stretch of the potential to provide a substantial boost Independent analyses for the council the road between the intersections with the to the local economy through the influx of have shown that the operation of the pack- Bruxner Highway and Jacksons Flat Road permanent and itinerant workers to the ing plant is expected to bring at least $8.9 considerably safer,” he said. -

Ruby Langford Ginibi: Bundjalung Historian, Writer and Educator

Ruby Langford Ginibi: Bundjalung Historian, Writer and Educator Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: The chapter considers the leadership of Ruby Langford Ginibi, whose writings recorded the history of the Bundjalung people of the Northern Rivers Region of New South Wales. She became prominent in national debates on Indigenous issues from the publication in 1988 of her autobiography, Don’t Take Your Love to Town until her death in 2011. Langford Ginibi was an effective voice in the attempt to persuade non-Aboriginal Australians to acknowledge the oppressive character of settler colonialism and its outcome in negative aspects of many Indigenous Australians’ lives in contemporary Australia. Above all, she drove understanding of the precariousness Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and the social wellbeing of their families when they left impoverished communities to seek waged work in far flung rural and in urban environments. Through her numerous publications, her research, public talks and interviews, Langford Ginibi made a major contribution to Australia that was recognized by numerous prestigious awards and an honorary doctorate. In 2012, a special issue of the Journal of the European Association of Studies on Australia commemorated her achievements. Key words: Aboriginal historians, Aboriginal writers, Indigenous rights, Bundjalung people, human rights, social justice In 1988 a Bundjalung woman, Ruby Langford (later Ruby Langford Ginibi), published her autobiography Don’t Take Your Love to Town to considerable applause, including the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s Award for Literature.1 Encouraged that she had an audience open to the story of the fraught life situations of Indigenous people, Langford Ginibi continued to produce works that informed non-Indigenous Australians about the past experiences of her people until shortly before her death in October 2011. -

19 Language Revitalisation: Community and School Programs Working Together

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 19 Language revitalisation: community and school programs working together Diane McNaboe1 and Susan Poetsch2 Abstract Since it was published in 2003 the New South Wales Aboriginal Languages K– 10 Syllabus has led to a substantial increase in the number of school programs operating in the state. It has supported the quality of those programs, and the status and recognition given to Aboriginal languages and cultures in the curriculum. School programs also complement community initiatives to revitalise, strengthen and share Aboriginal languages in New South Wales. As linguistic and cultural knowledge increases among adult community members, school programs provide a channel for them to continue to develop their own skills and knowledge and to pass on this heritage. This paper takes Wiradjuri as an example of language revitalisation, and describes achievements in adult language learning and the process of developing a school program with strong input from community. A brief history of Wiradjuri language revitalisation Wiradjuri is one of the central inland New South Wales (NSW) languages (Wafer & Lissarrague 2008, pp. 215–25). In recent decades various language teams have investigated and analysed archival sources for Wiradjuri and collected information from both written and oral sources (Büchli 2006, pp. 58–60). These teams include Grant and Rudder (2001a, b, c, d; 2005), Hosking and McNicol (1993), McNicol and Hosking (1994) and Donaldson (1984), as well as Christopher Kirkbright, George Fisher and Cheryl Riley, who have been working with Wiradjuri people in and near Sydney. -

Kyogle Local Environmental Plan No\ 18

2011 No 389 New South Wales Kyogle Local Environmental Plan No 18 under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 I, the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure, make the following local environmental plan under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. (09/03328) TOM GELLIBRAND As delegate for the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure Published LW 29 July 2011 Page 1 2011 No 389 Clause 1 Kyogle Local Environmental Plan No 18 Kyogle Local Environmental Plan No 18 under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 1 Name of Plan This Plan is Kyogle Local Environmental Plan No 18. 2 Commencement This Plan commences on the day on which it is published on the NSW legislation website. 3 Land to which Plan applies This Plan applies to certain land to which Interim Development Order No 1—Shire of Kyogle and Interim Development Order No 1—Shire of Terania apply. Page 2 2011 No 389 Kyogle Local Environmental Plan No 18 Amendment of Interim Development Order No 1—Shire of Kyogle Schedule 1 Schedule 1 Amendment of Interim Development Order No 1—Shire of Kyogle [1] Clause 2 Insert in alphabetical order in clause 2 (1): Aboriginal object means any deposit, object or other material evidence (not being a handicraft made for sale) relating to the Aboriginal habitation of an area of New South Wales, being habitation before or concurrent with (or both) the occupation of that area by persons of non-Aboriginal extraction, and includes Aboriginal remains. Aboriginal place of heritage significance means an area of land, the general location of which is identified in an Aboriginal heritage study adopted by the Council after public exhibition that is: (a) the site of one or more Aboriginal objects or a place that has the physical remains of pre-European occupation by, or is of contemporary significance to, the Aboriginal people. -

I Hall Revitalisation Project

Disability Inclusion Action Plan Final 5 June 2017 Universal Design Quality Information Document: Disability Inclusion Action Plan - Final Purpose: Mandatory compliance with NSW State Government requirements for preparation of a Disability Inclusion Action Plan by all NSW local governments; preparation of a standalone plan by Kyogle Council Prepared by: Manfred Boldy, Director Planning and Environment, Kyogle Council Reviewed by: Lachlan Black, Principal Planner, Kyogle Council Authorised by: Graham Kennett, General Manager, Kyogle Council Address Kyogle Council 1 Stratheden Street Kyogle NSW 2474 Australia ABN 15 726 771 237 5 June 2017 Revision History Revision Revision Date Details Authorised Name/Position 1,0 3 May 2017 Preliminary Draft for Council Lachlan Black, Principal Planner; Reviewer Review 1.1 4 May 2017 Draft Final Report Graham Kennett, General Manager; Approver 2.0 8 May 2017 Draft Report Adopted for Council Resolution – date to be advised Public Exhibition 3.0 13 June 2017 Final Adoption by Council Council Resolution – 13 June 2017 © Kyogle Council. All rights reserved; 2017 Kyogle Council has prepared this document for the sole use of the government department and its agents specified in this document for the purposes of supporting an application for the grant of financial assistance for the nominated project (see Project Title). No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of the Kyogle Council. Kyogle Council undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document in any other manner than the stated purpose of the document. Disability Inclusion Action Plan 5 June 2017 Acknowledgement of Country Kyogle Council acknowledges the Traditional Lands of the Bundjalung people on which our community is located and we acknowledge Elders both past and present. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Year 5 Music and HASS

Dance Dance ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER HISTORIES AND CULTURES LIVINGMotion CULTURES Transfer – Motion Transfer DANCE#702A48 #702A48 Remedial Practice Remedial Practice #94901F #94901F Creating Tradition Creating Tradition #0D588C #0D588C YEAR 5 Department of Education Dance Dance LIVING CULTURES – YEAR 5 Motion Transfer Motion Transfer DANCE#702A48 #702A48 Remedial Practice Remedial Practice #94901F #94901F CLAPSTICKSCreating Tradition Creating Tradition #0D588C #0D588C Learners undertake an inquiry into an Aboriginal instrument – the clapstick – before listening to a range of traditional and contemporary Aboriginal song and dance to explore the way clapsticks communicate meaning. Finally, students will make a set of their own clapsticks with an Aboriginal Sharer of Knowledge. CROSS CURRICULUM PRIORITY and practices of various cultural groups in relation to a specific time, event or custom Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures Critical & Creative Thinking Organising idea 1 Inquiring – identifying, exploring and organising information Australia has two distinct Indigenous groups: Aboriginal and ideas Peoples and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, and within Organise and process information those groups there is significant diversity. Level 4 – analyse, condense and combine relevant Organising idea 4 information from multiple sources Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies have Generating ideas, possibilities and actions many Language Groups. Imagine possibilities and connect ideas ACHIEVEMENT STANDARDS Level 4 – combine ideas in a variety of ways and from a Music range of sources to create new possibilities Students explain how the elements of music are used to communicate meaning in the music they listen to, compose and perform. They use rhythm, pitch and Learning Goals form symbols and terminology to compose and Learners will: perform music. -

Ntscorp Limited Annual Report 2010/2011 Abn 71 098 971 209

NTSCORP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 ABN 71 098 971 209 Contents 1 Letter of Presentation 2 Chairperson’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 NTSCORP’s Purpose, Vision & Values 8 The Company & Our Company Members 10 Executive Profiles 12 Management & Operational Structure 14 Staff 16 Board Committees 18 Management Committees 23 Corporate Governance 26 People & Facilities Management 29 Our Community, Our Service 30 Overview of NTSCORP Operations 32 Overview of the Native Title Environment in NSW 37 NTSCORP Performing the Functions of a Native Title Representative Body 40 Overview of Native Title Matters in NSW & the ACT in 2010-2011 42 Report of Performance by Matter 47 NTSCORP Directors’ Report NTSCORP LIMITED Letter OF presentation THE HON. JennY MacKlin MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, RE: 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the Commonwealth Government 2010–2013 General Terms and Conditions Relating to Native Title Program Funding Agreements I have pleasure in presenting the annual report for NTSCORP Limited which incorporates the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. Yours sincerely, MicHael Bell Chairperson NTSCORP NTSCORP ANNUAL REPORT 10/11 – 1 CHAIrperson'S Report NTSCORP LIMITED CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Company looks forward to the completion of these and other ON beHalF OF THE directors agreements in the near future. NTSCORP is justly proud of its involvement in these projects, and in our ongoing work to secure and members OF NTSCORP, I the acknowledgment of Native Title for our People in NSW. Would liKE to acKnoWledGE I am pleased to acknowledge the strong working relationship with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

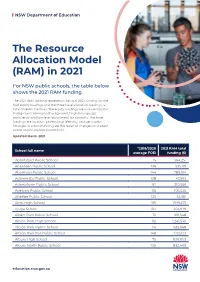

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

The Byron Shire Echo

OPEN FOR BUSINESS SINCE 1986! LONG LIVE THE PRINTED REALM The Byron Shire Echo • Volume 34 #52 • Wednesday, June 3, 2020 • www.echo.net.au News Corp scraps print Finally – table service! for paid online subs Mandy Nolan ‘I guess there had been talk here and there that papers were dying From June 29, nearly 100 regional and digital subscriptions were the newspapers, owned by US citizen latest, but we absolutely didn’t see and multi-billionaire Rupert Mur- this coming’. doch, will cease print operations. Another employee, who wished News Corp announced they will to also remain anonymous, is a move the (mostly free) titles to single parent. They said, ‘I felt like behind an online paywall. my job was secure. I had a car loan, Locally this includes the Byron a personal loan and I live alone. It News, the Northern Star, the Ballina will impact me heavily. I don’t know Advocate and the Tweed Daily News. if I can get another job, or if I have to Some communities will now be move in with my mum.’ without a local newspaper for the first time in generations. Politicians only winners A longtime journalist for a local from the decision News Corp newspaper, who asked to remain anonymous, said, ‘What hap- Both Tania and her colleagues pens when a local paper disappears? believe that many in the community Whether paid or free, the common will struggle with a digital format. thread is lost – communities lose a ‘The older demographic will point of connection for finding out definitely struggle without a print anything; from the most mundane version.