Bioregions of NSW: Cobar Peneplain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Prospectus

Cobar Shire Cobar Shire is located in western New South Wales, about 700 kilometres north-west of Sydney and 650 kilometres north of Canberra. Cobar is on the crossroads of three major highways – the Kidman Way linking Melbourne to Brisbane, the Barrier Highway linking Sydney to Adelaide via Broken Hill and the Wool Track linking the Sunraysia area to Queensland. Cobar Shire is home to around 5,000 people, the majority of whom live in the town of Cobar. The Shire is also made up of grazing leases and villages, with small villages at Euabalong, Euabalong West, Mount Hope and Nymagee. The Shire encompasses a total land area of about 46,000 square kilometres. The Shire's prosperity is built around the thriving mining - copper, lead, silver, zinc, gold - and pastoral industries, which are strongly supported by a wide range of attractions and activities, that attract around 120,000 visitors to the Shire a year. Rail and air infrastructure include regular freight trains to Sydney, a recently upgraded airport, a daily bus service to Dubbo and Broken Hill and freight and courier options available for all goods and services. Cobar boasts a strong and reliable workforce which has a wide range of skills, particularly in mining, manufacturing and supporting industries, trades, retail and agriculture. A good supply of general labour is available to meet the needs of new and expanding businesses. There is ample land available for development, both serviced and un-serviced. There is a wide variety of housing in Cobar, including town blocks of varying size and zoning, rural residential blocks and rural holdings. -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Technical Report on the Peak Gold Mines, New South Wales, Australia

NEW GOLD INC. TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE PEAK GOLD MINES, NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA NI 43-101 Report Qualified Persons: Ian T. Blakley, P.Geo. Richard J. Lambert, P.Eng. March 25, 2013 RPA Inc.55 University Ave. Suite 501 I Toronto, ON, Canada M5J 2H7 I T + 1 (416) 947 0907 www.rpacan.com Report Control Form Document Title Technical Report on the Peak Gold Mines, New South Wales, Australia Client Name & Address New Gold Inc. 3110-666 Burrard Street Vancouver, British Columbia V6C 2X8 Document Reference Status Final Project # 1973 & Version 0 Issue No. Issue Date March 25 , 2013 Lead Author Ian T. Blakley (Signed) “Ian T. Blakley” Richard J. Lambert (Signed) “Richard J. Lambert” Peer Reviewer William E. Roscoe (Signed) “William E. Roscoe” Project Manager Approval William E. Roscoe (Signed) “William E. Roscoe” Project Director Approval Richard J. Lambert (Signed) “Richard J. Lambert” Report Distribution Name No. of Copies Client RPA Filing 1 (project box) Roscoe Postle Associates Inc. 55 University Avenue, Suite 501 Toronto, ON M5J 2H7 Canada Tel: +1 416 947 0907 Fax: +1 416 947 0395 [email protected] www.rpacan.com TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 1-1 Technical Summary ....................................................................................................... 1-4 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ -

Cobar Shire Council

All communicotions to be addressed Cobor Shire Council Offices: to the General Manager 36 Linsley Street P.O. Box 223 Cobar NSW 2835 Cobor NSW 2835 ABN 71 579 717 155 Telephone: (02) 6836 5888 Shsr~ Facsimile: (02) 6836 5889 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cobar.nsw.gov.au EMP Inquiry In your reply please quote: Submission No. 15 Reference: E5-1/13946 “Regional Centre in Western NSW” KER:NFH th Tuesday 29 July 2003 The Secretary Standing Committee on Employment and Workplace Relations House ofRepresentatives Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Sir/Madam Subject: SUBMISSION — INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN PAID EMPLOYMENT Please find attached Council’s submission in relation to the House ofRepresentatives enquiryinto increasing participation in paid employment. Yours faithfully K.E. Roberts HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGER Attach.... HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON EMPLOYMENT AND WORKPLACE RELATIONS lAUG 2003 RECEIVED Cohar - On the crossroads of the Kidman Way and the Barrier Highway COBAR SHIRE COUNCIL SUBMISSION — INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN PAID EMPLOYMENT Cobar Shire Council is a rural, local government authority located in far west NSW, approximately 295 kilometres west ofDubbo and 711 kilometres west ofSydney. The Council serves an area of some 44,065 square kilometres with a population of approximately 7,500. Cobar Shire Council believes that ‘measures’ can be implemented to increase the level of participation in paid employment, in the form of labour market flexibility, employer and employee assistance/incentives. As a local government authority, and one of four major employers in the shire, Cobar Shire Council has always found it increasingly difficult to attract and retain qualified staff due to the following: 1. -

Table of Contents

Biolink koala conservation review Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 6 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE NSW POPULATION .............................................................. 6 Current distribution ................................................................................................... 6 Size of NSW koala population .................................................................................... 8 4. INFORMING CHANGES TO POPULATION ESTIMATES .......................................... 12 Bionet Records and Published Reports .................................................................... 15 Methods – Bionet records ................................................................................... 15 Methods – available reports ................................................................................ 15 Results .................................................................................................................. 16 The 2019 Fires .......................................................................................................... 22 Methods ............................................................................................................... 22 Results .................................................................................................................. 23 Data Deficient -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality. -

Australian Gold and Copper Limited (ACN 633 936 526)

Prospectus INITIAL PUBLIC OFFERING Prospectus for the offer of a minimum of 35,000,000 Shares at an issue price of A$0.20 each to raise $7,000,000 (Minimum Subscription) and a maximum of 50,000,000 Shares at an issue price of A$0.20 each to raise up to A$10,000,000 (Maximum Subscription) (Offer), including a priority offer of 5,000,000 Shares to Existing Magmatic Shareholders and Existing NSR Shareholders (Priority Offer). Lead Manager: Taylor Collison Limited For personal use only Australian Gold and Copper Limited (ACN 633 936 526) This document is important and it should be read in its entirety. If you are in any doubt as to the contents of this document, you should consult your sharebroker, solicitor, professional adviser, banker or accountant without delay. This Prospectus is issued pursuant to section 710 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The securities offered by this Prospectus are considered to be highly speculative. IMPORTANT INFORMATION provide financial product advice in respect of its securities or any other financial products. Offer This Prospectus is important and you should read it in its The offer contained in this prospectus (this Prospectus) is entirety, along with each of the documents incorporated by an offer for a Minimum Subscription of 35,000,000 Shares reference, prior to deciding whether to invest in the and a Maximum Subscription of up to 50,000,000 Shares Company’s Shares. There are risks associated with an in Australian Gold and Copper Ltd ACN 633 936 526 investment in the Shares, and you must regard the Shares (AGC, the Company, we or us) for subscription at A$0.20 offered under this Prospectus as a highly speculative each to raise a minimum of A$7,000,000 and up to a investment. -

Cobar Library Local History List.Xlsx

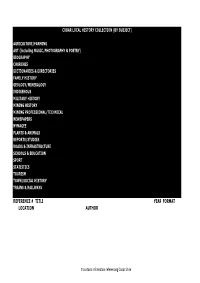

COBAR LOCAL HISTORY COLLECTION (BY SUBJECT) AGRICULTURE/FARMING ART (including MUSIC, PHOTOGRAPHY & POETRY) BIOGRAPHY CHURCHES DICTIONARIES & DIRECTORIES FAMILY HISTORY GEOLOGY/MINERALOGY INDIGENOUS MILITARY HISTORY MINING HISTORY MINING PROFESSIONAL/TECHNICAL NEWSPAPERS NYMAGEE PLANTS & ANIMALS REPORTS/STUDIES ROADS & INFRASTRUCTURE SCHOOLS & EDUCATION SPORT STATISTICS TOURISM TOWN/SOCIAL HISTORY TRAINS & RAILWAYS REFERENCE # TITLE YEAR FORMAT LOCATION AUTHOR # contains information referencing Cobar Shire AGRICULTURE/FARMING # contains information referencing Cobar Shire 264634 Forests, fleece & prickly pears # 1997 Paperback LOCAL HISTORY/508.94/KRU Karl Kruszelnicki 242345 Atlas of New South Wales pastoral stations : a guide to the property names of the larger holdings in NSW and the ACT LOCAL HISTORY/630.0994/ALI Terrance Alick 2004 Paperback 264675 100 years : celebrating 100 years of natural resource progress in the Western Division of NSW # LOCAL HISTORY/994.49/BAR Maree Barnes & Geoff Wise 2003 Paperback Originally published by West 2000 Plus : Western people looking after the Western Division and NSW Department of Sustainable Natural Resouces Reprinted in 2010 by the Western Cathment Management Authority A collection of images, history and stories from the Western Division of New South Wales 237005 Gunderbooka : a 'stone country' story # 2000 Paperback LOCAL HISTORY/994.49/MAI George Main A story of how the landscape of far-western NSW imposed itself upon people and shaped them Starting with the first Aborigines the cycle moves through the pastoralists and back to indigenous ownership 264724 Western lands # 1990 Paperback LOCAL HISTORY/994.49/WES Published by the Western Lands Commission, Department of Lands A booklet providing information on land administration in the Western Division, including facts on the region's history, economy and natural resources ART (including MUSIC, PHOTOGRAPHY & POETRY) # contains information referencing Cobar Shire 264682 Annual report 2016 # 2016 A5 booklet LOCAL HISTORY/709/OUT Outback Arts 264683 Artbark. -

Grey Box (Eucalyptus Microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia

Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia: A guide to the identification, assessment and management of a nationally threatened ecological community Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Glossary the Glossary at the back of this publication. © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercialised use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Public Affairs - Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2610 Australia or email [email protected] Disclaimer The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and is valid as at June 2012. The Australian Government is not liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. CONTENTS WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE? 1 NATIONALLY THREATENED ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITIES 2 What is a nationally threatened ecological community? 2 Why does the Australian Government list threatened ecological communities? 2 Why list the Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia as -

BOOKBINDING .;'Ft1'

• BALOS BOOKBINDING .;'fT1'. I '::1 1 I't ABORIGINAL SONGS FROM THE BUNDJALUNG AND GIDABAL AREAS OF SOUTH-EASTERN AUSTRALIA by MARGARET JANE GUMMOW A thesis submitted in fulfihnent ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department ofMusic University of Sydney July 1992 (0661 - v£6T) MOWWnO UllOI U:lpH JO .uOW:lW :lip Ol p:ll1l:>W:l<J ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I wish to express my most sincere thanks to all Bundjalung and Gidabal people who have assisted this project Many have patiently listened to recordings ofold songs from the Austra1ian Institute ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, sung their own songs, translated, told stories from their past, referred me to other people, and so on. Their enthusiasm and sense ofurgency in the project has been a continual source of inspiration. There are many other people who have contributed to this thesis. My supervisor, Dr. Allan Marett, has been instrumental in the compilation of this work. I wish to thank him for his guidance and contributions. I am also indebted to Dr. Linda Barwick who acted as co-supervisor during part of the latter stage of my candidature. I wish to thank her for her advice on organising the material and assistance with some song texts. Dr. Ray Keogh meticulously proofread the entire penultimate draft. I wish to thank him for his suggestions and support. Research was funded by a Commonwealth Postgraduate Research Award. Field research was funded by the Austra1ian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Several staff members at AlATSIS have been extremely helpful. -

And Challenger Gold Li

GOLDEN CROSS RESOURCES LTD ABN 65 063 075 178 304/66 Berry Street NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2060 Phone (02) 9922 1266 Fax (02) 9922 1288 28 April 2016 MARCH 2016 QUARTERLY ACTIVITIES & CASHFLOW REPORT Key Points: HQ Mining Resources Holding Pty Ltd (HQ Mining) completes off-market takeover bid for the Company Short-term loan facility provided by HQ Mining Divestment of non-core assets Extension of the West Wyalong JV with Argent Minerals Limited Further results received for metallurgical program at Copper Hill Project CORPORATE HQ Mining’s takeover bid for Golden Cross Resources Limited (“GCR” or the “Company”), which was announced on 24 November 2015 and closed on 29 January 2016, resulted in HQ Mining acquiring a voting power in the Company of 76.46%. As disclosed in its Bidder’s Statement, HQ Mining recognises the Company’s immediate funding requirement to progress the Prefeasibility Study (“PFS”) at the Copper Hill Project. HQ Mining’s intention is to facilitate a pro-rata rights issue to raise sufficient funds to complete a PFS. HQ Mining has indicated its desire for that issue to be completed in July/August 2016. Pending the proposed capital raising, the Directors have secured the necessary funding to support the ongoing activities of the Company through the divestment of non-core assets and the provision of a short-term loan facility by HQ Mining. Non-Core Asset Divestment During the quarter the Company received $300,000 from the divestment of non-core assets. These included the divestment of: the Mt Boppy royalty for $200,000, For personal use only the interest in the Wagga Tank Joint Venture for $40,000, and EL7390 for $60,000 (as announced on 23 October 2015) Golden Cross Resources Limited: March 2016 Quarterly Page 1 of 15 HQ Mining Loan Facility The Company entered into a loan agreement with HQ Mining for $320,000 on normal commercial terms and payable in three tranches. -

Areference Grammar of Gamilaraay, Northern New

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF GAMILARAAY, NORTHERN NEW SOUTH WALES Peter Austin Department of Linguistics La Trobe University Bundoora. Victoria 3083 Australia first draft: 29th March 1989 this draft: 8th September 1993 2 © Peter K. Austin 1993 THIS BOOK IS COPYRIGHT. DO NOT QUOTE OR REPRODUCE WITHOUT PERMISSION Preface The Gamilaraay people (or Kamilaroi as the name is more commonly spelled) have been known and studied for over one hundred and sixty years, but as yet no detailed account of their language has been available. As we shall see, many things have been written about the language but until recently most of the available data originated from interested amateurs. This description takes into account all the older materials, as well as the more recent data. This book is intended as a descriptive reference grammar of the Gamilaraay language of north-central New South Wales. My major aim has been to be as detailed and complete as possible within the limits imposed by the available source materials. In many places I have had to rely heavily on old data and to ‘reconstitute’ structures and grammatical patterns. Where possible I have included comparative notes on the closely related Yuwaalaraay and Yuwaaliyaay languages, described by Corinne Williams, as well as comments on patterns of similarity to and difference from the more distantly related Ngiyampaa language, especially the variety called Wangaaypuwan, described by Tamsin Donaldson. As a companion volume to this grammar I plan to write a practically-oriented description intended for use by individuals and communities in northern New South Wales. This practical description will be entitled Gamilaraay, an Aboriginal Language of Northern New South Wales.