Sasa Naturally Disturbed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

September 2011 South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board

Government of South Australia South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board September 2011 South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board Partnerships in protecting rockholes: project overview PARTNERSHIPS IN PROTECTING ROCKHOLES: PROJECT OVERVIEW Tom Jenkin1, Melissa White2, Lynette Ackland1 Glen Scholz2 and Mick Starkey1 September 2011 Report to the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board 1South Australian Native Title Services (SANTS) 2Department for Water (DFW) DISCLAIMER The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. This report may be cited as: Jenkin T, White M, Ackland L, Scholz G and Starkey M (2011). Partnerships in protecting rockholes: project overview. A report to the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. Cover images: Field work participants at Murnea Rock-hole, Moonaree Station and top of granite outcrop at Thurlga Homestead, Gawler Ranges © South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the authors and the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the General Manager, South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board Railway Station Building, PO Box 2227, Port Augusta, SA, 5700 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been supported and funded by the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resource Management Board. -

Caralue Bluff Conservation Park) Proclamation 2012 Under Section 30(1) of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972

No. 61 4323 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 6 SEPTEMBER 2012 CONTENTS Page Appointments, Resignations, Etc. ............................................ 4324 Corporations and District Councils—Notices ......................... 4381 Environment Protection Act 1993—Notices ........................... 4325 Fair Trading Act 1987—Notice .............................................. 4327 Fisheries Management Act 2007—Notice ............................... 4327 Liquor Licensing Act 1997—Notices...................................... 4327 Mining Act 1971—Notices ..................................................... 4328 Motor Vehicles Act 1959—Notice .......................................... 4326 Proclamations .......................................................................... 4340 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................. 4386 Radiation Protection and Control Act 1982—Notice .............. 4336 REGULATIONS Development Act 1993 (No. 204 of 2012) .......................... 4373 Intervention Orders (Prevention of Abuse) Act 2009 (No. 205 of 2012) ............................................................ 4376 Development Act 1993 (No. 206 of 2012) .......................... 4378 Roads (Opening and Closing) Act 1991—Notices .................. 4336 Waterworks Act 1932—Notice ............................................... 4339 Water Mains and -

Land of the Black Stump Dr Charles Fahey

Land of the Black Stump Dr Charles Fahey Let me commence by stating how happy I am to have the opportunity to come to Launceston and attend this seminar. It is almost twenty years since I first came to Launceston to teach at the University of Tasmania, or as the Launceston campus was then called, the TSIT. During my short stay in Launceston I had the good fortune to participate in the formation of the Launceston Historical Society. It is quite gratifying to see that this society is still going strong. Since leaving Launceston I have lived in the former Victorian goldmining city of Bendigo, and have worked on the Bendigo and Melbourne campuses of LaTrobe University. In the past twenty years my research interests have focused on two major themes: the historical behaviour of the labour market and the historical evolution of rural and regional Australia. It is this second area that I will talk on today. A number of years ago Professor Alan Mayne, then of Melbourne University and now of the University of South Australia, and myself worked together on an ARC funded project to look at family and community in the Victorian goldfields. The main research for this work was undertaken using the resources of the office of Births, Deaths and Marriages and the great collection of personal papers from the gold rush deposited in the State Library of Victoria. Fortunately as part of the project we engaged a research scholar from the United States to undertake a doctorate. Our student, now Dr Sara Martin, had an interest in material culture and examined a range of objects and buildings and told the story of the people who used and occupied these. -

New Discoveries from the Gawler Ranges: Greisen-Style Mineralisation in Hiltaba Suite Granite and a Regional Stratigraphic Marker in the Upper GRV

New discoveries from the Gawler Ranges: Greisen-style mineralisation in Hiltaba Suite granite and a regional stratigraphic marker in the upper GRV Mario Werner Carmen Krapf, Stacey McAvaney, Ben Nicolson & Mark Pawley Geological Survey of South Australia Talk Outline GSSA Projects & Programs • Southern Gawler Ranges Margin Project • Mineral Systems Drilling Program (MSDP) • Role of field mapping in drilling program • What have we done and where can you find it? Recent Discoveries • Greisen-style mineralisation in Hiltaba Suite granite → direct contribution to the understanding of the area’s metallogenetic evolution • Regional stratigraphic marker in the upper GRV → important stratigraphic knowledge for explorers in the GRV region Southern Gawler Ranges Margin Project & Mineral Systems Drilling Program • Improve geological understanding of GRV-Hiltaba units and underlying basement • Characterisation of various mineral systems associated with GRV-Hiltaba magmatism • Define lithological and structural controls on mineralisation MSDP Drilling and Mapping areas Six Mile Hill Peltabinna Mount Double Role of field mapping in MSDP • Stratigraphy • Regional vs deposit-scale alteration systems • Constrain interpretation of geophysics • Structural geology and tectonic evolution Field Mapping: documentation and delivery 669 field observations 169 rock samples 62 geochemistry analyses 57 thin sections 13 geochronology samples available via MSDP Mapping Products Regolith Map Southern GRV Margin available via Greisen-style alteration and mineralisation -

Prioritising Rock-Holes of Aboriginal and Ecological Significance in the Gawler Ranges Melissa White

Government of South Australia South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board December 2008 South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board Prioritising rock-holes of Aboriginal and ecological significance in the Gawler Ranges Melissa White Prioritising rock-holes of Aboriginal and ecological significance in the Gawler Ranges Melissa White Knowledge and Information Division Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 31st December 2008 Report DWLBC 2009/08 Knowledge and Information Division Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 25 Grenfell Street, Adelaide GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone National (08) 8463 6946 International +61 8 8463 6946 Fax National (08) 8463 6999 International +61 8 8463 6999 Website www.dwlbc.sa.gov.au Disclaimer The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. © Government of South Australia, through the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 2009 This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Chief Executive, Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001. -

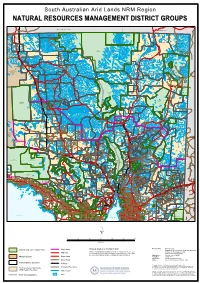

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

M01: Mineral Exploration Licence Applications

M01 Mineral Exploration Licence Applications 27 September 2021 Resources and Energy Group L4 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide SA 5000 http://energymining.sa.gov.au/minerals GPO Box 320, ADELAIDE, SA 5001 http://energymining.sa.gov.au/energy_resources Phone +61 8 8463 3000 http://map.sarig.sa.gov.au Email [email protected] Earth Resources Information Sheet - M1 Printed on: 27/09/2021 M01: Mineral Exploration Licence Applications Year Lodged: 1996 File Ref. Applicant Locality Fee Zone Area (km2 ) 250K Map 1996/00118 NiCul Minerals Limited Mount Harcus area - Approx 400km 2,415 Lindsay, WNW of Marla Woodroffe 1996/00185 NiCul Minerals Limited Willugudinna Hill area - Approx 823 Everard 50km NW of Marla 1996/00260 Goldsearch Ltd Ernabella South area - Approx 519 Alberga 180km NW of Marla 1996/00262 Goldsearch Ltd Marble Hill area - Approx 80km NW 463 Abminga, of Marla Alberga 1996/00340 Goldsearch Ltd Birksgate Range area - Approx 2,198 Birksgate 380km W of Marla 1996/00341 Goldsearch Ltd Ayliffe Hill area - Approx 220km NW 1,230 Woodroffe of Marla 1996/00342 Goldsearch Ltd Musgrave Ranges area - Approx 2,136 Alberga 180km NW of Marla 1996/00534 Caytale Pty Ltd Bull Hill area - Approx 240km NW of 1,783 Woodroffe Marla Year Lodged: 1997 File Ref. Applicant Locality Fee Zone Area (km2 ) 250K Map 1997/00040 Minex (Aust) Pty Ltd Bowden Hill area - Approx 300 WNW 1,507 Woodroffe of Marla 1997/00053 Mithril Resources Limited Mt Cooperina Area - approx. 360 km 1,013 Mann WNW of Marla 1997/00055 Mithril Resources Limited Oonmooninna Hill Area - approx. -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia 2001 ______

____________________________________________________ A VEGETATION MAP OF THE WESTERN GAWLER RANGES, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 2001 ____________________________________________________ by T. J. Hudspith, A. C. Robinson and P.J. Lang Biodiversity Survey and Monitoring National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia 2001 ____________________________________________________ i Research and the collation of information presented in this report was undertaken by the South Australian Government through its Biological Survey of South Australia Program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the South Australian Government or the Minister for Environment and Heritage. The report may be cited as: Hudspith, T. J., Robinson, A. C. and Lang, P. J. (2001) A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia (National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia, Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia). ISBN 0 7590 1029 3 Copies may be borrowed from the library: The Housing, Environment and Planning Library located at: Level 1, Roma Mitchell Building, 136 North Terrace (GPO Box 1669) ADELAIDE SA 5001 Cover Photograph: A typical Triodia covered hillslope on Thurlga Station, Gawler Ranges, South Australia. Photo: A. C. Robinson. ii _______________________________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia ________________________________________________________________________________ PREFACE ________________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia is a further product of the Biological Survey of South Australia The program of systematic biological surveys to cover the whole of South Australia arose out of a realisation that an effort was needed to increase our knowledge of the distribution of the vascular plants and vertebrate fauna of the state and to encourage their conservation.