The Defences of Macau Forts, Ships and Weapons Over 450 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineers of the Renaissance

Bertrand Gille Engineers of the Renaissance . II IIIII The M.I.T.Press Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts ' ... � {' ( l..-'1 b 1:-' TA18 .G!41J 1966 METtTLIBRARY En&Jneersor theRenaissance. 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0020119043 Copyright @ 1966 by Hermann, Paris Translated from Les ingenieurs de la Renaissance published by Hermann, Paris, in 1964 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 66-27213 Printed in Great Britain Contents List of illustrations page 6 Preface 9 Chapter I The Weight of Tradition 15 2 The Weight of Civilization 3 5 3 The German School 55 4 The First Italian Generation 79 5 Francesco di Giorgio Martini 101 Cj 6 An Engineer's Career -Leonardo da Vinci 121 "'"" f:) 7 Leonardo da Vinci- Technician 143 ��"'t�; 8 Essay on Leonardo da Vinci's Method 171 �� w·· Research and Reality ' ·· 9 191 �' ll:"'t"- 10 The New Science 217 '"i ...........,_ .;::,. Conclusion 240 -... " Q: \.., Bibliography 242 �'� :::.(' Catalogue of Manuscripts 247 0 " .:; Index 254 � \j B- 13 da Page Leonardo Vinci: study of workers' positions. List of illustrations 18 Apollodorus ofDamascus: scaling machine. Apollodorus of Damascus: apparatus for pouring boiling liquid over ramparts. 19 Apollodorus ofDamascus: observation platform with protective shield. Apollodorus of Damascus: cover of a tortoise. Apollodorus ofDamascus: fire lit in a wall andfanned from a distance by bellows with a long nozzle. 20 Hero of Byzantium: assault tower. 21 Hero of :Byzantium: cover of a tortoise. 24 Villard de Honnecourt: hydraulic saw; 25 Villard de Honnecourt: pile saw. Villard de Honnecourt: screw-jack. , 26 Villard de Honnecourt: trebuchet. Villard de Honnecourt: mechanism of mobile angel. -

Proquest Dissertations

PANORAMA, POWER, AND HISTORY: VASARI AND STRADANO'S CITY VIEWS IN THE PALAZZO VECCHIO Pt.I by Ryan E. Gregg A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2008 © 2008 Ryan E. Gregg AH Rights Reserved UMI Number: 3339721 Copyright 2008 by Gregg, Ryan E. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3339721 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Painted topographical views of cities and their environs appear throughout the mid-sixteenth-century fresco decorations of the Palazzo Vecchio. This project focuses primarily on the most extensive series, those in the Quartiere di Leone X. Giorgio Vasari and his assistant Giovanni Stradano painted the five rooms of this apartment between 1556 and 1561. The city views take one of three forms in each painting: as a setting for a historical scene, as the background of an allegory, or as the subject of the view itself. -

A Plan of 1545 for the Fortification of Kelso Abbey | 269

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 141 (2011), 269–278 A PLAN OF 1545 FOR THE FORTIFICATION OF KELSO ABBEY | 269 A plan of 1545 for the fortification of Kelso Abbey Richard Fawcett* ABSTRACT It has long been known from surviving correspondence that the Italian gunfounder Archangelo Arcano prepared two drawings illustrating proposals for the fortification of Kelso Abbey, following its capture by the English army under the leadership of the Earl of Hertford in 1545. It had been assumed those drawings had been lost. However, one of them has now been identified and is here published, together with a brief discussion of what it can tell us about the abbey in the mid-16th century. The purpose of this contribution is to bring to in fact, represent that abbey (Atherton 1995– wider attention a pre-Reformation plan that 6), though there was then no basis for offering had for long been thought to represent Burton- an alternative identification. on-Trent Benedictine Abbey, but that has It was Nicholas Cooper who established recently been identified by Nicholas Cooper the connection between the drawing and as a proposal of 1545 for fortifying Kelso’s a hitherto presumed lost proposal for the Tironensian Abbey. The plan in question fortification of Kelso, when he was working (RIBA 69226) was among a small number of on the architectural activities of William Paget papers deposited by the Marquess of Anglesey at Burton-on-Trent for a paper to be delivered with the Royal Institute of British Architects, to the Society of Antiquaries of London.2 whose collections are now absorbed into the Proposals for fortifying Kelso were known Drawings and Archives Collections of the to have been drawn by the Italian gunfounder Victoria and Albert Museum. -

Black Powder Free

FREE BLACK POWDER PDF Ally Sherrick | 368 pages | 04 Aug 2016 | Chicken House Ltd | 9781910655269 | English | Somerset, United Kingdom Dixie Gun Works muzzleloading, blackpowder and rare antique gun supplies. Gunpowderalso known as the retronym Black Powder powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powderis the earliest known chemical explosive. The sulfur and charcoal act as fuels while the saltpeter is an oxidizer. Gunpowder was invented in 9th-century China as one Black Powder the Four Great Inventionsand spread throughout most parts of Eurasia by the end of Black Powder 13th century. Gunpowder is classified as a low explosive because of its relatively slow decomposition rate and consequently low brisance. Low explosives deflagrate i. Ignition of gunpowder packed behind a projectile generates enough pressure to force the shot from the muzzle at high speed, but usually not enough force to rupture the gun barrel. Gunpowder thus makes a good propellant, but is less suitable for shattering rock or fortifications with its low-yield explosive power. However, by transferring enough energy from the Black Powder gunpowder to the mass of the cannonball, and then from the Black Powder to the opposing fortifications by way of the Black Powder ammunition eventually a bombardier may wear down an opponent's Black Powder defenses. Gunpowder was widely used to fill fused artillery shells and used in mining and civil engineering projects until the second half of the 19th century, when the first Black Powder explosives were put into use. The earliest Black Powder formula for gunpowder appeared in the 11th century Song dynasty text, Wujing Zongyao Complete Essentials from the Military Classicswritten by Zeng Gongliang Black Powder and A slow match for flame throwing mechanisms using the siphon principle and for fireworks and rockets is mentioned. -

Seek for Help and Protective Measures

www.ias.gov.mo Seek for Help and Telephone numbers for assistance and Protective Measures information inquiry on family services Domestic Violence influences everyone * Social Welfare Bureau Zero tolerance in a family. Protect yourself and your Family Service Division for against any abuse! children from domestic violence and end the * Types of Domestic Violence * suffering. Be brave and seek help! * Emergency Support Services We can provide the following protective measure for 24 hour helpline for women - Lai Yuen Centre : you and your family Helpline for child protection - Child Protection Centre Life Hope Hotline - Macau Caritas Domestic violence is considered as any 24 hour helpline for victims of sexual harassment - General Sheng Kung Hui physical, mental or sexual ill- treatment in a protective family relationship or in an equivalent measures Temporary shelter service * Integrated Family Support Services relationship, repetitive injury behavior and Family Service Centre “Kin Wa” of Social Service Section of the Methodist Church single injury behavior through strong or Tamagnini of Macao Barbosa serious means. Financial assistance for Joy Family Integrated Service Centre of immediate needs the Salvation Army Lok Chon Centre of the General Union *Physical violence: non-accidentally of Neighborhood Association of Macau causing long-term physical trauma or Immediate judiciary Ilha Verde assistance Fai Chi Kei Family and Community pain, including physical violence, Services Complex of the Macau Federation of Trade Unions using sharps/weapons. Central Family Service Centre of the Women’s Free healthcare service District General Association of Macau sexual abuse of *Sexual abuse: ‘Centro de Apoio Múltiplo à Família children or forcing a partner to “Alegria em Harmonia” da Associação Support services for Geral das Mulheres de Macau have sex. -

Validation of a Parametric Approach for 3D Fortification Modelling: Application to Scale Models

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W1, 2013 3D-ARCH 2013 - 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25 – 26 February 2013, Trento, Italy VALIDATION OF A PARAMETRIC APPROACH FOR 3D FORTIFICATION MODELLING: APPLICATION TO SCALE MODELS K. Jacquot, C. Chevrier, G. Halin MAP-Crai (UMR 3495 CNRSMCC), ENSA Nancy, 54000 Nancy, France (jacquot, chevrier, halin)@crai.archi.fr Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: architectural heritage, bastioned fortifications, parametric modelling, knowledge based, scale model, 3D surveys ABSTRACT: Parametric modelling approach applied to cultural heritage virtual representation is a field of research explored for years since it can address many limitations of digitising tools. For example, essential historical sources for fortification virtual reconstructions like plans-reliefs have several shortcomings when they are scanned. To overcome those problems, knowledge based-modelling can be used: knowledge models based on the analysis of theoretical literature of a specific domain such as bastioned fortification treatises can be the cornerstone of the creation of a parametric library of fortification components. Implemented in Grasshopper, these components are manually adjusted on the data available (i.e. 3D surveys of plans-reliefs or scanned maps). Most of the fortification area is now modelled and the question of accuracy assessment is raised. A specific method is used to evaluate the accuracy of the parametric components. The results of the assessment process will allow us to validate the parametric approach. The automation of the adjustment process can finally be planned. The virtual model of fortification is part of a larger project aimed at valorising and diffusing a very unique cultural heritage item: the collection of plans-reliefs. -

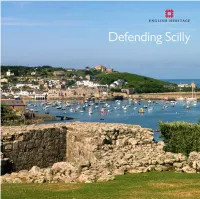

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Download the PDF File

Sacha Dobler AbruptEarthChanges.com Black Death and Abrupt Earth Changes in the 14th century 1290-1350: Abrupt Earth changes, astronomical, tectonic and meteorological events leading up to and culminating at the Black Death period at 1348 By Sacha Dobler 2017 © abruptearthchanges.com Fig. 1 14th Century engraving of the Black Death, depicting extreme lightning? Or fire from the sky devastating a town, a victim of plague? with spots distributed over the entire body. Image: http://www.historytoday.com 1 - (In the years before the Black Death in Europe), ”between Cathay and Persia there rained a vast rain of fire, falling in flakes like snow and burning up mountains and plains and other lands, with men and women; and then arose vast masses of smoke; and whoever beheld this died within the space of half an hour; and likewise any man or woman who looked upon those who had seen this(..)”.1 --Philip Ziegler writing about the years before the out break of the Black Death “The middle of the fourteenth century was a period of extraordinary terror and disaster to Europe. Numerous portents, which sadly frightened the people, were followed by a pestilence which threatened to turn the continent into an unpeopled wilderness. For year after year there were signs in the sky, on the earth, in the air, all indicative, as men thought, of some terrible coming event. In 1337 a great comet appeared in the heavens, its far- extending tail sowing deep dread in the minds of the ignorant masses. During the three succeeding years the land was visited by enormous flying armies of locusts, which descended in myriads upon the fields, and left the shadow of famine in their track. -

Teachers' Guide for Military Technology

Military Technology TO THE TEACHER OBJECTIVES OF THIS UNIT: To help students think about warfare from the perspective of the technology used, thus linking military history to economic history and the history of science. TEACHING STRATEGIES: This unit can be used to help students grasp the long-term military confrontation between Chinese dynasties and the northern steppe societies. This unit lends itself to a comparative approach as many of the weapons and techniques have close counterparts in other parts of the world. Most of the images in this unit were taken from wood block illustrations in traditional Chinese books. To make this unit more challenging, teachers could raise questions about the advantages and limits of such sources. WHEN TO TEACH: Although the material in this unit derives primarily from Song dynasty sources, it deals with weapons and defensive systems in use for many centuries, and even in a chronologically-organized course could be used earlier or later to good effect. If used as part of instruction on the Song period, students would get more from the unit if they have already been introduced to the struggle between the Song and its northern neighbors, culminating with the Mongols. This unit would also be appropriate for use in teaching comparative military history. The Song period is a good point to take stock of China's military technology. First, warfare was central to the history of the period. The confrontation between the Song and the three successive non-Chinese states to the north (Liao, Jin, and Yuan) made warfare not only a major preoccupation for those in government service, but also a stimulus to siegecraft crossbows and rethinking major intellectual issues. -

A Case Study of Macau, China

© 2002 WIT Press, Ashurst Lodge, Southampton, SO40 7AA, UK. All rights reserved. Web: www.witpress.com Email [email protected] Paper from: The Sustainable City II, CA Brebbia, JF Martin-Duque & LC Wadhwa (Editors). ISBN 1-85312-917-8 Urban regeneration and the sustainability of colonial built heritage: a case study of Macau, China L Chaplain School of Language and Translation, Macau Polytechnic Institute, China Abstract This paper presents a case study of late twentieth century urban regeneration in the former Portuguese colonial territory of Macau – now designated as a Special Administrative Region of China (Macau SAR). Regeneration in this context is defined and discussed here under the headings: regeneration through reclamation; regeneration through infi-astructure investment; regeneration through preserva- tion. The new Macau SAR Government continues to differentiate Macau fi-om its neighbors by promoting the legacy of a tourist-historic city with a unique archi- tectural fhsion of both West and East as an integral feature of the destination’s marketing strategy. However, regeneration of urban space through reclamation has led to a proliferation of high rise buildings with arguable architectural merit which diminish the appeal of the overwhelmed heritage properties and sites. Future plans for the development of the territory are outlined, including major projects designed to enhance the tourism product through purpose-built leisure and entertainment facilities. 1 Introduction The urban regeneration of the City of Macau can be attributed to significant developments which occurred in the last century of its four hundred years of exis- tence as a Portuguese occupied territory located in China’s southern province of Guangdong – formerly known as Canton. -

3.Water Environment

Report on the State of the Environment of Macao 2019 3. Water Environment In 2019, the Government of the Macao SAR put into use the 3.1 Quality of Potable Water fourth water supply pipeline to ensure water supply safety; DPSIR Framework optimized wastewater treatment facilities, launched the Macao Peninsula WWTP optimization project; pushed forward the D Driving Forces P Pressures S States I Impacts R Responses pollution control and management for the water environment, completed the sewage discharges interception project along the Status coast of Areia Preta. It also published the trial standard for the surface water environment, progressively strengthened water In 2019, water supply in Macao remained unaffected by salt tides, same environment monitoring, conducted microplastics survey in the as 2018. coastal area of Macao, and completed the study on water quality Despite the chloride concentration of treated water from the Ilha Verde monitoring scheme for the maritime areas of Macao, in order to Water Treatment Plant increased in 2019 compared to 2018, the quality of strengthen the protection of the water environment. potable water in Macao was maintained at a low salinity level (green)1 (see This chapter will illustrate the status and evolution of the water Figure 3.2 and Table 3.1). environment indicators through the quality and consumption of In 2019, the qualified rate of coliform bacteria in the distribution networks potable water, the water quality of maritime areas, and wastewater of Macao was above 99%, which was similar to that of 2018 and was in treatment. compliance with the requirements of relevant law2 (see Figure 3.3 and Table 3.1). -

Italians Fire Lance This Week

(\ l'. :·\ \.,,R''z;".: .· A'· ... '\- ·>.·. .M .:· · G·· · - - ......_,.__ .·.. :-····· ··.. •.•,·.......... .... ~- ·.·.·.·.·.·.·.. ·.· .. :-:·:·:·:·:·:-· -···· .........- .· ·.···· Published in the interest of the personnel of White Sands Missile Range , Volume 25-Number 39 Friday, December 6, 1974 A range first Italians fire Lance t his week For the first time in history, Logistical support for the and by Ft. Bliss, Tex., units Italian Army troop units are firings was provided by a U.S. and serving as range sponsor firing missiles at White Sands that operate Orogrande Range will be the Lance project office unit from Ft. Sill, the 1st Camp. Missile Range this week. Battalion, 12th Field Artillery, in the Materiel Test Division of A six-round series of annual Providing technical support WSMR Army Missile Test and service practice firings of the Evaluation Directorate. Lance, the medium-range Scoring the firing units will artillery weapon system, is be umpires from Italy and planned. Four rounds wete Pear/ Harbor recalled from the U.S. Army Field scheduled for Thursday, with Artillery Missile Systems two rounds to go today. Making his first inaugural address on March 4, 1933, Evaluation Group based at Ft. The firing series is a President Franklin D. Roosevelt told a country deep in Sill. On hand in advisory roles milestone in the program of depression, "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself." will be representatives of the deployment and use of the Eight years later, the word 'fear' was to take on new meaning U.S. Army Missile Command Lance, a rugged and highly in the annals of American history. In the wake of war in Europe, headquartered at Redstone mobile system designed for the world paid little attention to a small country, Japan, in the Arsenal, Ala., and the LTV support of ground combat Pacific and its plans for the expansion of its empire.