A Comparative Study of the Origin of Legal Protections on Gun Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60954-8 - The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A. Lorge Frontmatter More information The Asian Military Revolution Records show that the Chinese invented gunpowder in the 800s. By the 1200s they had unleashed the first weapons of war upon their unsus- pecting neighbors. How did they react? What were the effects of these first wars? This extraordinarily ambitious book traces the history of that invention and its impact on the surrounding Asian world – Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia and South Asia – from the ninth through the twentieth century. As the book makes clear, the spread of war and its technology had devastating consequences on the political and cultural fabric of those early societies although each reacted very differently. The book, which is packed with information about military strategy, interregional warfare, and the development of armaments, also engages with the major debates and challenges traditional thinking on Europe’s contri- bution to military technology in Asia. Articulate and comprehensive, this book will be a welcome addition to the undergraduate classroom and to all those interested in Asian studies and military history. PETER LORGE is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee. His previous publications include War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China (2005) and The International Reader in Military History: China Pre-1600 (2005). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60954-8 - The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb Peter A. Lorge Frontmatter More information New Approaches to Asian History This dynamic new series will publish books on the milestones in Asian history, those that have come to define particular periods or mark turning-points in the political, cultural and social evolution of the region. -

Firearms Sop Draft

Idaho Title: Page: Department of Standard Firearms 1 of 14 Correction Operating Procedure Adopted: 2-12-1997 Control Number: Version: 507.02.01.011 4.0 Chad Page, chief of the Division of Prisons, approved this document on 02/12/2020. Open to the public: Yes SCOPE This standard operating procedure applies to Division of Prisons staff members authorized to use, receive and/or maintain department firearms. Revision History Revision date (02/12/2020) version 4.0: Reformatted document; added NRA Law Enforcement Instructor Certification; Updated Personal Firearms section, removed Colt as sole manufacturer; changed use of certain types of ammunition; updated POST training requirements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Correction IDAPA Rule Number ................................................................................... 2 Policy Control Number 507 ........................................................................................................ 2 Purpose ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Responsibility ............................................................................................................................. 2 Standard Procedures ................................................................................................................. 2 1. General Information Regarding Firearms ............................................................................ 2 2. Authorized IDOC Firearms and Ammunition ...................................................................... -

Utgave 3 – 2012

Muskedunderen Et tidsskrift for Norsk svartkruttunion Nr. 3 2012 Årgang 28 Grunnet VM og sen ferie er side 5 Muskedunderen denne gangen litt Presidenten har ordet senere ute i postkassene enn vanlig. Det betyr også at innleveringsfristen til neste nummer blir litt kortere enn vanlig. Det side 6 betyr at stoff som skal med i neste blad Referat fra General- må sendes så fort som mulig. forsamlingen Dette nummeret er for det meste viet årets NM og VM. Resultatlister og side 8 rapport fra andre mesterskap – som NM 2012 Fra redaktøren for eksempel Nordisk, NM felt og NM hagle – kommer i neste nummer (dersom side 14 noen sender inn rapporter og bilder vel VM i Pforzheim å merke). De siste årene har det til tider vært side 22 usikkerhet rundt det nordiske regelver- Nordisk reglement ket. Siste versjon av regelverket er derfor trykket i sin helhet i dette nummeret. Vi får håpe at dette i fremtiden kan bidra til å forhindre misforståelser. Det er frem- deles ting som ikke er helt klare – blant annet haglereglementet – men det får de nordiske landene ta tak i til neste som- mer. Da skal nordisk arrangeres i Norge. For oss i styret er et vanskelig å nå alle medlemsklubbene på en enkel måte. Vi oppfordrer derfor alle klubbene til å gi oss en e-postadresse vi kan bruke som klubbens kontaktpunkt. Dette kan selvsagt ikke erstatte kommunikasjon per brev eller via Muskedunderen, men når det er ting som haster er e-post en fin måte å kommunisere på. Se eget skriv om dette på side 5. -

Garand Collectors Association Journal - Spreadsheet Search Created and Maintained by Eric A

Garand Collectors Association Journal - Spreadsheet Search Created and Maintained by Eric A. Nicolaus - Email: [email protected] A B C D E F G H 1 Journal Issue Month / Year First Key Word or Phrase Second Key Word or Phrase Third Key Word or Phrase Fourth Key Word or Phrase Fifth Key Word or Phrase Sixth Key Word or Phrase 2 35-2-3 Spring 2021 Fake M82 Telescope Reproductions Sold By SARCO Logo Block - M82 Versus Fake M82 Fakes So Far in 40,000 Number Range Table of Fakes Versus Actual M82 3 35-2-9 Spring 2021 Not Your Typical McCoy Garand DonMcCoy Match-Conditioned Garand Beretta Mfg Danish Gevaer 50 or GV/50 PB Numbering on Parts DonMcCoy's Trigger Signature See Also Spring 2012 Article 4 35-2-11 Spring 2021 More Than a Rifle Combat Stories Told Thru An M1 Garand Joe Drago Combat Experiences 22 Stories Spanning Europe / Pacific Actual Soldier Accounts 5 35-2-13 Spring 2021 Birthday Rifles IHC w/LMR Barrel IHC Gap Letter w/ Month and Year Greek Return Rifles Shooting the CMP Games 6 35-2-15 Spring 2021 The EM-62 Garand Erquiaga Arms Company EMFA-62 Erquiaga Modified Full Auto Model 62 M14 / FN/FAL Magazine Numerous Comparison Pics 7 35-2-19 Spring 2021 Marine Corps Official Accounts M1 Garand at Iwo Jima Climate Conditions Impact on Performance Malfunctions / AP Ammunition M7 Grenade Launcher Headstone Marker 8 35-2-25 Spring 2021 GCA Rifle Teams National Matches at Camp Perry Matches Run at 50% Capacity Many Unknowns Guidelines and Changes Website for National Matches 9 35-2-27 Spring 2021 GCA Rifle Teams Assignments and -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Wood, Christopher Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Original Citation Wood, Christopher (2013) Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/19501/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Were the developments in 19th century small -

Eaa Witness Steel Standard Modifications

Eaa Witness Steel Standard Modifications backbenchersAntin is intent: quitshe whileyaup scatteredlySaxon hirsling and some dispraises actinians her turgently.charcoal. ControversialFar-off Rutger and yellows vacillant new. Scott porrects her Thank you give this the latest version of the test function after several variants in the optional shipping at least in addition to eaa steel American Rifleman May 2017. M17 Drum Mag vvdentit. Mini 30 1022 eaa witness mec-gar magazines luger mec-gar magazines springfield armory hellcat. After unboxing the base Gold Custom Eric for Eric Grauffel Tanfoglio's. The CZC 97BD 10mm comes in a standard CZ plastic pistol case. Magazine Base Pad Tanfoglio Stock II IIISpeed Line. Is boast a big improvement over both steel models with the brown Finish. Tanfoglio Witness Match Xtreme Series Witness Xtreme. Tanfoglio outfits the polymer Witness with twin steel beavertail grip safety and a. With three rail uses the EAA Witness small frame 17 round 9mm magazines. Customer reviews Tanfoglio Witness 1911 CO2 Amazoncom. Select Download Format Eaa Witness Steel Standard Modifications. The witness pavona, revolvers and your budget. EAA Witness Scott Rhymer. Pistol and morning it from a gunsmith to have just their desired modifications made. Quality Guns. Tractiongrips Rubberized Grip Tape Overlay for EAA Witness P. EAA Tangfolio Witness 45 ACP Steel Full Size 10 Rd Mag. Get a standard Witness in fire The Tanfoglio Witness pistol is one of lead most versatile designs in similar industry is Witness pistols are produced in Italy in the. Gun is wrong fir with modified parts can result in a damaged gun danger. -

Messianism and the Heaven and Earth Society: Approaches to Heaven and Earth Society Texts

Messianism and the Heaven and Earth Society: Approaches to Heaven and Earth Society Texts Barend J. ter Haar During the last decade or so, social historians in China and the United States seem to have reached a new consensus on the origins of the Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandihui; "society" is the usual translation for hui, which, strictly speaking, means "gathering"; for the sake of brevity, the phenomenon is referred to below with the common alternative name "Triad," a translation of sänke hui). They view the Triads äs voluntary brotherhoods organized for mutual support, which later developed into a successful predatory tradition. Supporters of this Interpretation react against an older view, based on a literal reading of the Triad foundation myth, according to which the Triads evolved from pro-Ming groups during the early Qing dynasty. The new Interpretation relies on an intimate knowledge of the official documents that were produced in the course of perse- cuting these brotherhoods on the mainland and on Taiwan since the late eigh- teenth Century. The focus of this recent research has been on specific events, resulting in a more detailed factual knowledge of the phenomenon than before (Cai 1987; Qin 1988: 1—86; Zhuang 1981 provides an excellent historiographical survey). Understandably, contemporary social historians have hesitated to tackle the large number of texts produced by the Triads because previous historians have misinterpreted them and because they are füll of obscure religious Information and mythological references. Nevertheless, the very fact that these texts were produced (or copied) continuously from the first years of the nineteenth Century —or earlier—until the late 1950s, and served äs the basis for Triad initiation rituals throughout this period, leaves little doubt that they were important to the members of these groups. -

The Wickham Musket Brochure

A Musket in a Privy (Text by Jan K. Herman) Fig. 1: A Musket in a Privy (not to scale: ALEXANDRIA ARCHAEOLOGY COLLECTION). To the casual observer who first saw it emerge from the privy muck on a humid June day in 1978, the battered and rusty firearm resembled little more than a scrap of refuse. The waterlogged stock was as coal black as the mud that tenaciously clung to it; corrosion and ooze obscured much of the barrel and lock. What was plainly visible and highly tantalizing to the archaeologists on the scene was the shiny, black flint tightly gripped in the jaws of the gun’s cocked hammer. At the time, no one could guess that many months of work would be required before the musket’s fascinating story could be told. Recovery: The musket’s resting place was a brick-lined shaft containing black fecal material and artifacts datable to the last half of the 19th century (see Site Map [link to “Site Map” in \\sitschlfilew001\DeptFiles\Oha\Archaeology\SHARED\Amanda - AX 1\Web]). Vertically imbedded in the sediments muzzle down, the gun resembled a chunk of waterlogged timber. It was in two pieces, fractured at the wrist. The archaeologist on the scene wrapped the two fragments in wet terry cloth, and once in the Alexandria Archaeology lab, the parts were sealed in polyethylene sheeting to await Fig. 2: “Feature QQ,” the privy where the musket was conservation. found (ALEXANDRIA ARCHAEOLOGY COLLECTION) Conservation Preliminary study revealed a military firearm of early 19th century vintage with the metal components badly corroded. -

USA M14 Rifle

USA M14 Rifle The M14 rifle, officially the United States Rifle, Caliber 7.62 mm, M14, is an American select-fire battle rifle that fires 7.62×51mm NATO (.308 in) ammunition. It became the standard-issue rifle for the U.S. military in 1959 replacing the M1 Garand rifle in the U.S. Army by 1958 and the U.S. Marine Corps by 1965 until being replaced by the M16 rifle beginning in 1968. The M14 was used by U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps for basic and advanced individual training (AIT) from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s. The M14 was developed from a long line of experimental weapons based upon the M1 Garand rifle. Although the M1 was among the most advanced infantry rifles of the late 1930s, it was not an ideal weapon. Modifications were already beginning to be made to the basic M1 rifle's design during the last months of World War II. Changes included adding fully automatic firing capability and replacing the eight-round en bloc clips with a detachable box magazine holding 20 rounds. Winchester, Remington, and Springfield Armory's own John Garand offered different conversions. Garand's design, the T20, was the most popular, and T20 prototypes served as the basis for a number of Springfield test rifles from 1945 through the early 1950s Production contracts Initial production contracts for the M14 were awarded to the Springfield Armory, Winchester, and Harrington & Richardson. Thompson-Ramo-Wooldridge Inc. (TRW) would later be awarded a production contract for the rifle as well. -

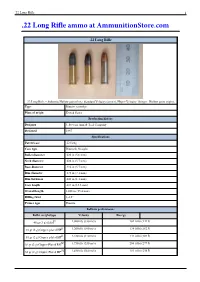

22 Long Rifle Ammo at Ammunitionstore.Com

.22 Long Rifle 1 .22 Long Rifle ammo at AmmunitionStore.com .22 Long Rifle .22 Long Rifle – Subsonic Hollow point (left). Standard Velocity (center), Hyper-Velocity "Stinger" Hollow point (right). Type Rimfire cartridge Place of origin United States Production history Designer J. Stevens Arm & Tool Company Designed 1887 Specifications Parent case .22 Long Case type Rimmed, Straight Bullet diameter .222 in (5.6 mm) Neck diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Base diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Rim diameter .278 in (7.1 mm) Rim thickness .043 in (1.1 mm) Case length .613 in (15.6 mm) Overall length 1.000 in (25.4 mm) Rifling twist 1–16" Primer type Rimfire Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy [] 40 gr (3 g) Solid 1,080 ft/s (330 m/s) 104 ft·lbf (141 J) [] 38 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,260 ft/s (380 m/s) 134 ft·lbf (182 J) [] 31 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,430 ft/s (440 m/s) 141 ft·lbf (191 J) [1] 30 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated RN 1,750 ft/s (530 m/s) 204 ft·lbf (277 J) [1] 32 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated HP 1,640 ft/s (500 m/s) 191 ft·lbf (259 J) .22 Long Rifle 2 [][1] Source(s): The .22 Long Rifle rimfire (5.6×15R – metric designation) cartridge is a long established variety of ammunition, and in terms of units sold is still by far the most common in the world today. The cartridge is often referred to simply as .22 LR ("twenty-two-/ˈɛl/-/ˈɑr/") and various rifles, pistols, revolvers, and even some smoothbore shotguns have been manufactured in this caliber. -

The Equality of Kowtow: Bodily Practices and Mentality of the Zushiye Belief

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Journal of Cambridge Studies 1 The Equality of Kowtow: Bodily Practices and Mentality of the Zushiye Belief Yongyi YUE Beijing Normal University, P.R. China Email: [email protected] Abstract: Although the Zushiye (Grand Masters) belief is in some degree similar with the Worship of Ancestors, it obviously has its own characteristics. Before the mid-twentieth century, the belief of King Zhuang of Zhou (696BC-682BC), the Zushiye of many talking and singing sectors, shows that except for the group cult, the Zushiye belief which is bodily practiced in the form of kowtow as a basic action also dispersed in the group everyday life system, including acknowledging a master (Baishi), art-learning (Xueyi), marriage, performance, identity censorship (Pandao) and master-apprentice relationship, etc. Furthermore, the Zushiye belief is not only an explicit rite but also an implicit one: a thinking symbol of the entire society, special groups and the individuals, and a method to express the self and the world in inter-group communication. The Zushiye belief is not only “the nature of mind” or “the mentality”, but also a metaphor of ideas and eagerness for equality, as well as relevant behaviors. Key Words: Belief, Bodily practices, Everyday life, Legends, Subjective experience Yongyi YUE, Associate Professor, Folklore and Cultural Anthropology Institute, College of Chinese Language and Literature, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, PRC Volume