Engineers of the Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

PANORAMA, POWER, AND HISTORY: VASARI AND STRADANO'S CITY VIEWS IN THE PALAZZO VECCHIO Pt.I by Ryan E. Gregg A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2008 © 2008 Ryan E. Gregg AH Rights Reserved UMI Number: 3339721 Copyright 2008 by Gregg, Ryan E. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3339721 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Painted topographical views of cities and their environs appear throughout the mid-sixteenth-century fresco decorations of the Palazzo Vecchio. This project focuses primarily on the most extensive series, those in the Quartiere di Leone X. Giorgio Vasari and his assistant Giovanni Stradano painted the five rooms of this apartment between 1556 and 1561. The city views take one of three forms in each painting: as a setting for a historical scene, as the background of an allegory, or as the subject of the view itself. -

Transfer of Islamic Science to the West

Transfer of Islamic Science to the West IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Prof. Dr. Ahmed Y. Al-Hassan Chief Editor: Prof. Dr. Mohamed El-Gomati All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Production: Savas Konur accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: December 2006 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 625 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2006 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

A Plan of 1545 for the Fortification of Kelso Abbey | 269

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 141 (2011), 269–278 A PLAN OF 1545 FOR THE FORTIFICATION OF KELSO ABBEY | 269 A plan of 1545 for the fortification of Kelso Abbey Richard Fawcett* ABSTRACT It has long been known from surviving correspondence that the Italian gunfounder Archangelo Arcano prepared two drawings illustrating proposals for the fortification of Kelso Abbey, following its capture by the English army under the leadership of the Earl of Hertford in 1545. It had been assumed those drawings had been lost. However, one of them has now been identified and is here published, together with a brief discussion of what it can tell us about the abbey in the mid-16th century. The purpose of this contribution is to bring to in fact, represent that abbey (Atherton 1995– wider attention a pre-Reformation plan that 6), though there was then no basis for offering had for long been thought to represent Burton- an alternative identification. on-Trent Benedictine Abbey, but that has It was Nicholas Cooper who established recently been identified by Nicholas Cooper the connection between the drawing and as a proposal of 1545 for fortifying Kelso’s a hitherto presumed lost proposal for the Tironensian Abbey. The plan in question fortification of Kelso, when he was working (RIBA 69226) was among a small number of on the architectural activities of William Paget papers deposited by the Marquess of Anglesey at Burton-on-Trent for a paper to be delivered with the Royal Institute of British Architects, to the Society of Antiquaries of London.2 whose collections are now absorbed into the Proposals for fortifying Kelso were known Drawings and Archives Collections of the to have been drawn by the Italian gunfounder Victoria and Albert Museum. -

Copying, Commonplaces, and Technical Knowledge: the Architect-Engineer As Reader

COPYING, COMMONPLACES, AND TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE: THE ARCHITECT-ENGINEER AS READER Alexander Marr I Recent work on the history of technology has drawn attention to the importance of manuscripts and, in particular, drawings for the design, construction, comprehension, and use of machines in the Renaissance and Early Modern period.1 Documents such as the workshop drawings of Antonio da Sangallo or the extensive extant papers of Heinrich Schick- hardt are now finding a place alongside better-known printed works, such as the ‘theatres of machines’ by Ramelli, Besson, and Bachot.2 Yet com- paratively little is known about the book ownership and reading habits of those artisans involved in the processes of machine design, construc- tion, and implementation. The present essay seeks to shed new light on these subjects, through an examination of an important – but somewhat neglected – manuscript compilation of text and images on technical top- ics (ranging from practical mathematics to building), made in the early seventeenth century by the French architect-engineer Jacques Gentillâtre (1578–c. 1623).3 To date, this manuscript has been discussed exclusively within the context of the theory and practice of architecture, yet the diversity of subjects with which it is concerned (notably the numerous uses to which machines may be put) demands that the document be 1 See e.g. Lefèvre W. (ed.), Picturing Machines, 1400–1700 (Cambridge, MA-London: 2004). 2 See the useful table of ‘Prominent Sources of Early Modern Machine Design’ in Lefèvre, “Introduction to Part I”, in idem, Picturing Machines 13–15. An important addition to this table is Ambroise Bachot’s theatre of machines: Gouuernail (Melun: 1598). -

Validation of a Parametric Approach for 3D Fortification Modelling: Application to Scale Models

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W1, 2013 3D-ARCH 2013 - 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25 – 26 February 2013, Trento, Italy VALIDATION OF A PARAMETRIC APPROACH FOR 3D FORTIFICATION MODELLING: APPLICATION TO SCALE MODELS K. Jacquot, C. Chevrier, G. Halin MAP-Crai (UMR 3495 CNRSMCC), ENSA Nancy, 54000 Nancy, France (jacquot, chevrier, halin)@crai.archi.fr Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: architectural heritage, bastioned fortifications, parametric modelling, knowledge based, scale model, 3D surveys ABSTRACT: Parametric modelling approach applied to cultural heritage virtual representation is a field of research explored for years since it can address many limitations of digitising tools. For example, essential historical sources for fortification virtual reconstructions like plans-reliefs have several shortcomings when they are scanned. To overcome those problems, knowledge based-modelling can be used: knowledge models based on the analysis of theoretical literature of a specific domain such as bastioned fortification treatises can be the cornerstone of the creation of a parametric library of fortification components. Implemented in Grasshopper, these components are manually adjusted on the data available (i.e. 3D surveys of plans-reliefs or scanned maps). Most of the fortification area is now modelled and the question of accuracy assessment is raised. A specific method is used to evaluate the accuracy of the parametric components. The results of the assessment process will allow us to validate the parametric approach. The automation of the adjustment process can finally be planned. The virtual model of fortification is part of a larger project aimed at valorising and diffusing a very unique cultural heritage item: the collection of plans-reliefs. -

Defending Scilly

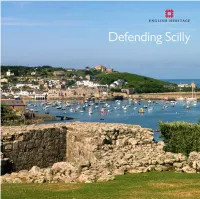

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Declared Enemies and Pacific Infidels: Spanish Doctrines of “Just War” in the Mediterranean and Atlantic1 Andrew W

Declared Enemies and Pacific Infidels: Spanish Doctrines of “Just War” in the Mediterranean and Atlantic1 Andrew W. Devereux Loyola Marymount University n december 1511, on successive Sundays of Advent, the Dominican friar Antonio de Montesinos delivered a series of rousing sermons from the pulpit of the main church of Santo Domingo in which he took the Castilian colonists of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola to Itask for their treatment of the Indians.2 The protests of Montesinos and his fellow Dominicans prompted King Ferdinand of Aragon (r. 1479–1516) to convene a junta in the Castilian city of Burgos in 1512 to examine the legality of the Spanish conquest of the Americas and the attendant treatment of the region’s inhabitants. One result of the meeting at Burgos was that the jurist and law professor Juan López de Palacios Rubios was commissioned to codify the Requerimiento, the document Castilian conquistadors were to read to indigenous peoples upon first contact. In no uncertain terms, the Requerimiento demanded of its listeners “that you acknowledge the Church as the Ruler and Superior of the whole world and the high priest called Pope, and in his name 1 The two descriptors both come courtesy of Bartolomé de Las Casas. In hisTratado comprobatorio del imperio soberano, he describes Turks and Moors as the declared enemies of Christendom (hostes públicos y enemigos). See Bartolomé de Las Casas, Tratados de Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, preface by Lewis Hanke and Manuel Giménez Fernández, 2 vols. (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1965), 1035. By contrast, in his Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, he describes the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas as “pacific infidels”infieles ( pacíficos). -

On a Human Scale. Drawing and Proportion of the Vitruvian Figure Veronica Riavis

7 / 2020 On a Human Scale. Drawing and Proportion of the Vitruvian Figure Veronica Riavis Abstract Among the images that describe the proportions of the human body, Leonardo da Vinci’s one is certainly the most effective, despite the fact that the iconic drawing does not faithfully follow the measurements indicated by Vitruvius. This research concerned the geometric analysis of the interpretations of the Vitruvian man proposed in the Renaissance editions of De Architectura, carried out after the aniconic editio princeps by Sulpicio da Veroli. Giovanni Battista da Sangallo drew the Vitruvian figure directly on his Sulpician copy, very similar to the images by Albrecht Dürer in The Symmetry of the Human Bodies [Dürer 1591]. Fra Giocondo proposes in 1511 two engravings of homo ad quadratum and ad circulum in the first Latin illustrated edition of De Architectura, while the man by Cesare Cesariano, author of the first version in vernacular of 1521, has a deformed body extension to adapt a geometric grid. Francesco di Giorgio Martini and Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara also propose significant versions believed to be the origin of Leonardo’s figuration due to the friendship that bound them. The man inscribed in the circle and square in the partial translation of Francesco di Giorgio’s De Architectura anticipates the da Vinci’s solution although it does not have explicit metric references, while the drawing by Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara reproduces a figure similar to Leonardo’s one. The comparison between the measures expressed by Vitruvius to proportion the man and the various graphic descriptions allows us to understand the complex story of the exegesis of the Roman treatise. -

Passing As Morisco

Figueroa 1 Passing as Morisco: Concealment and Slander in Antonio Mira de Amescua’s El mártir de Madrid MELISSA FIGUEROA ABSTRACT This essay analyzes the notion of ‘passing’ in Antonio Mira de Amescua’s play El mártir de Madrid (1610) and how it unveils the effects of concealment and slander in a hegemonic Christian society dealing with religious, ethnic, and gender anxiety in the aftermath of the expulsion of Moriscos from Spain (1609). Drawing upon contemporary studies on the concept of ‘passing,’ the essay reflects on what happens when pretending to belong to a religious affiliation, an ethnic group, or the opposite sex yields negative consequences for the character who is trying to pass. Besides examining different instances of ‘passing’ related to ethnicity, religion, and gender, the essay pays attention to the historical events that inspired Mira de Amescua’s play; i.e. the martyrdom of the Spanish Pedro Navarro in North Africa (1580) after having passed as Muslim and returned to Christianity. In addition, the essay identifies several contemporary sources and puts them into dialogue with the play. In 1580, a native of Madrid named Pedro Navarro was martyred in Morocco. Although little is known about how he was taken captive or how long he lived in North Africa, he became a symbol of devotion and religious zeal. A secret practitioner of Catholicism, Navarro was captured and sentenced to death by Islamic authorities as he attempted to return to Spain. Even after his tongue was cut off, he continued preaching the Catholic faith. His loyalty to the Church, however, is striking because Pedro Navarro also embraced Islam and passed as Muslim during his captivity. -

The Invented World of Mariano Taccola

Leonardo_36-2_099-178 3/14/03 12:20 PM Page 135 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The Invented World ABSTRACT The Sienese artist-engineer of Mariano Taccola: Mariano Taccola left behind five books of annotated drawings, presently in the collections of Revisiting a Once-Famous the state libraries of Florence and Munich. Taccola was well known in Siena, and his draw- Artist-Engineer of 15th-Century Italy ings were studied and copied by artists of the period, probably serving as models for Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks. However, his work has received little Lawrence Fane attention from scholars and students in recent times. The author, a sculptor, has long been interested in Taccola’s drawings for his studio projects. Although Taccola lacked the fine drawing hand displayed by many of his contemporaries, his he name Mariano Taccola (1382–ca. 1453) as an engineer. His drawings, which inventive work may appeal T especially to viewers today. means little to most students of the Renaissance or to the gen- he carefully organized in bound Based on examination of the eral public, and yet he was a prominent figure in Siena in the notebooks, were studied by contem- original drawings, the author 15th century, leaving behind hundreds of extraordinary draw- porary artists, copied by followers discusses the qualities that ings of machines, war implements and other inventions, set in and distributed to military leaders make Taccola’s drawings unique fascinating environments with figures and animals. Taccola, who and statesmen throughout Europe. and considers what Taccola’s called himself “the Sienese Archimedes,” was primarily known These pages were probably known to intentions may have been in making them. -

The Scaling Ladders of Leonardo Da Vinci: Art and Engineering

The Scaling Ladders of Leonardo da Vinci: Art and Engineering John Garton1 In an increasingly war-torn Europe, Renaissance artists of the highest rank occasionally devoted themselves to military design. Francesco di Giorgio de- vised various assault weapons, Andrea Verrocchio and Hans Burgkmair each designed armo ur, Michelangelo created ramparts, and Albrecht Dürer wrote a treatise on fortifications — to name a few. Even artists averse to violence could hardly ignore the constant threat of war and its impact on the cityscape. Leonardo’s notebooks, particularly the drawings assembled by Pompeo Leoni in the 1560s to create the Codex Atlanticus, chronicle Leonardo’s involve- ment with weaponry design while serving Duke Ludovico Sforza of Milan. These drawings may never have been intended to form an organized military treatise; indeed, they range in style from quick, conceptual sketches to care- fully shaded, perspectival showpieces probably meant to impress the duke or his advisors. The little-known sheet of drawings at the center of this essay dates to around 1487–90, a period of intense absorption for Leonardo in the arts of warfare. While the drawing’s provenance has received some scholarly attention regarding possible origins in the Codex Atlanticus, its innovative technology remains poorly understood (fig. 7.1).2 The sheet, now in the Pier- pont Morgan Library, reveals much about Leonardo’s thinking as a military 1 My introduction to Leonardo studies began in 1998 in a seminar at the Metropoli- tan Museum of Art with Carmen Bambach, Associate Curator of Drawings and Prints. I choose to revisit Leonardo here, in honour of Colin Eisler, with the hopes that further scrutiny of the works of that polymath from Vinci might reflect warmly on Colin’s eclectic interests and ceaseless work ethic. -

The ORDER of Malta and the DEFENCE of TRIPOLI 1530 -1551 •

tHE ORDER OF MALtA AND THE DEFENCE OF TRIPOLI 1530 -1551 • by Andrew P. Vella To appreciate the full meaning of the responsibility of the Order of Malta to defend Tripoli, one must think of the Mediterranean Sea and Mediterranean countries as divided between two major forces or powers, spiritual as well as physical, viz. Islam and Christendom. The dividing line is usually drawn from Northern Italy to Sicily, Malta and Tripoli: the Eastern part belonging to the Turkish Sultan who claimed dominion over Asia Minor and the Arabian peninsula, Egypt and all Northern Africa; and the rest of the Western part claimed by the Spanish Emperor. The two halves of the Mediterranean, in the words of Braudel, were indeed two political zones under different banners . .- It was Ferdinand of Aragon who had seized Mersa-el-Kebir or Mazarquivir in 1505, Penon de Velez in 1509 and Bugia in 1510. Algiers surrendered in the same year, and on June 5th 1510, the King of Tlemcen agreed at Oran to a five-year peace and the payment of a yearly tribute to the King of Aragon. The latter'S commander in the field, Pedro Navarro (1), then remained free to conquer Tripoli. His fleet stopped in Malta to collect some guides who had a good :knowledge of that country; he also embarked the Maltese Giuliano Abela to act as their pilot (2). • The text printed here is a concise and revised version of my lecture as published in Libya in History: Historical Conference 1968 (Beirtd-Lebanon 1969), pp.349-82. 1.