Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ritual Landscapes and Borders Within Rock Art Research Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (Eds)

Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (eds) and Vangen Lindgaard Berge, Stebergløkken, Art Research within Rock and Borders Ritual Landscapes Ritual Landscapes and Ritual landscapes and borders are recurring themes running through Professor Kalle Sognnes' Borders within long research career. This anthology contains 13 articles written by colleagues from his broad network in appreciation of his many contributions to the field of rock art research. The contributions discuss many different kinds of borders: those between landscapes, cultures, Rock Art Research traditions, settlements, power relations, symbolism, research traditions, theory and methods. We are grateful to the Department of Historical studies, NTNU; the Faculty of Humanities; NTNU, Papers in Honour of The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and The Norwegian Archaeological Society (Norsk arkeologisk selskap) for funding this volume that will add new knowledge to the field and Professor Kalle Sognnes will be of importance to researchers and students of rock art in Scandinavia and abroad. edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Steberglokken cover.indd 1 03/09/2015 17:30:19 Ritual Landscapes and Borders within Rock Art Research Papers in Honour of Professor Kalle Sognnes edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 9781784911584 ISBN 978 1 78491 159 1 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2015 Cover image: Crossing borders. Leirfall in Stjørdal, central Norway. Photo: Helle Vangen Stuedal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. -

Engineers of the Renaissance

Bertrand Gille Engineers of the Renaissance . II IIIII The M.I.T.Press Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts ' ... � {' ( l..-'1 b 1:-' TA18 .G!41J 1966 METtTLIBRARY En&Jneersor theRenaissance. 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0020119043 Copyright @ 1966 by Hermann, Paris Translated from Les ingenieurs de la Renaissance published by Hermann, Paris, in 1964 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 66-27213 Printed in Great Britain Contents List of illustrations page 6 Preface 9 Chapter I The Weight of Tradition 15 2 The Weight of Civilization 3 5 3 The German School 55 4 The First Italian Generation 79 5 Francesco di Giorgio Martini 101 Cj 6 An Engineer's Career -Leonardo da Vinci 121 "'"" f:) 7 Leonardo da Vinci- Technician 143 ��"'t�; 8 Essay on Leonardo da Vinci's Method 171 �� w·· Research and Reality ' ·· 9 191 �' ll:"'t"- 10 The New Science 217 '"i ...........,_ .;::,. Conclusion 240 -... " Q: \.., Bibliography 242 �'� :::.(' Catalogue of Manuscripts 247 0 " .:; Index 254 � \j B- 13 da Page Leonardo Vinci: study of workers' positions. List of illustrations 18 Apollodorus ofDamascus: scaling machine. Apollodorus of Damascus: apparatus for pouring boiling liquid over ramparts. 19 Apollodorus ofDamascus: observation platform with protective shield. Apollodorus of Damascus: cover of a tortoise. Apollodorus ofDamascus: fire lit in a wall andfanned from a distance by bellows with a long nozzle. 20 Hero of Byzantium: assault tower. 21 Hero of :Byzantium: cover of a tortoise. 24 Villard de Honnecourt: hydraulic saw; 25 Villard de Honnecourt: pile saw. Villard de Honnecourt: screw-jack. , 26 Villard de Honnecourt: trebuchet. Villard de Honnecourt: mechanism of mobile angel. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} O Segredo Dos Medicis by Michael White

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} O Segredo dos Médicis by Michael White WALTON FORD PANCHA TANTRA. At first glance, Walton Ford’s large-scale, highly-detailed watercolors of animals may recall the prints of 19th century illustrators John James Audubon and Edward Lear, and others of the colonial era. But a closer look reveals a complex and disturbingly anthropomorphic universe, full of symbols, sly jokes, and allusions to the 'operatic' nature of traditional natural history themes. The beasts and birds populating this contemporary artist's life-size paintings are never mere objects, but dynamic actors in allegorical struggles: a wild turkey crushes a small parrot in its claw; a troupe of monkeys wreak havoc on a formal dinner table, an American buffalo is surrounded by bloodied white wolves. The book's title derives from The Pancha Tantra, an ancient Indian book of animal tales considered the precursor to Aesop’s Fables. This large-format edition includes an in-depth exploration of Walton Ford’s oeuvre, a complete biography, and excerpts from his textual inspirations: Vietnamese folktales and the letters of Benjamin Franklin, the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini and Audubon’s Ornithological Biography. Book Review: The Medici Secret by Michael White. The story begins with a flood in a Milanese church crypt in the 1960’s. But it’s not just any church crypt. It is the crypt housing the mortal remains of the Medici family. Back in the present, scientists have been given unprecedented access to the Medici burials, but when the lead Professor, Carlin Mackenzie, is found murdered in the pop-up lab within the church, the question is, what had he found? His niece, Edie Granger, is another member of the research term, and she wants to find out. -

"Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(S): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol

Architecture and Music Reunited: A New Reading of Dufay's "Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(s): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 740-775 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1261923 . Accessed: 03/11/2014 00:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Renaissance Society of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.147.172.89 on Mon, 3 Nov 2014 00:42:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Architectureand Alusic Reunited: .V A lVewReadi 0 u S uperRosarum Floresand theCathedral ofFlorence. byMARVIN TRACHTENBERG Theproportions of the voices are harmoniesforthe ears; those of the measure- mentsare harmoniesforthe eyes. Such harmoniesusuallyplease very much, withoutanyone knowing why, excepting the student of the causality of things. -Palladio O 567) Thechiasmatic themes ofarchitecture asfrozen mu-sic and mu-sicas singingthe architecture ofthe worldrun as leitmotifithrough the histories ofphilosophy, music, and architecture.Rarely, however,can historical intersections ofthese practices be identified. -

A Plan of 1545 for the Fortification of Kelso Abbey | 269

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 141 (2011), 269–278 A PLAN OF 1545 FOR THE FORTIFICATION OF KELSO ABBEY | 269 A plan of 1545 for the fortification of Kelso Abbey Richard Fawcett* ABSTRACT It has long been known from surviving correspondence that the Italian gunfounder Archangelo Arcano prepared two drawings illustrating proposals for the fortification of Kelso Abbey, following its capture by the English army under the leadership of the Earl of Hertford in 1545. It had been assumed those drawings had been lost. However, one of them has now been identified and is here published, together with a brief discussion of what it can tell us about the abbey in the mid-16th century. The purpose of this contribution is to bring to in fact, represent that abbey (Atherton 1995– wider attention a pre-Reformation plan that 6), though there was then no basis for offering had for long been thought to represent Burton- an alternative identification. on-Trent Benedictine Abbey, but that has It was Nicholas Cooper who established recently been identified by Nicholas Cooper the connection between the drawing and as a proposal of 1545 for fortifying Kelso’s a hitherto presumed lost proposal for the Tironensian Abbey. The plan in question fortification of Kelso, when he was working (RIBA 69226) was among a small number of on the architectural activities of William Paget papers deposited by the Marquess of Anglesey at Burton-on-Trent for a paper to be delivered with the Royal Institute of British Architects, to the Society of Antiquaries of London.2 whose collections are now absorbed into the Proposals for fortifying Kelso were known Drawings and Archives Collections of the to have been drawn by the Italian gunfounder Victoria and Albert Museum. -

Pyramid #3/117

Stock #37-2717 CONTENTS I N THIS FROM THE EDITOR ....................3 CITY OF LIGHTS, CITY OF BLACKOUTS.......4 ISSUE by Jon Black The recent release of GURPS Hot Spots: Renaissance Venice is the perfect opportunity to plan trips to other Hot EAST BERLIN.......................17 Spots throughout history . and beyond. by Matt Wehmeier Paris of the early 20th century embodied the good and bad of the new century; it was a City of Lights, City of Blackouts. EIDETIC MEMORY: VICTORIA 2100 .......24 This mini-supplement provides a perfect primer to Paris of by David L. Pulver this era, including GURPS City Stats details. Discover import- VILLA DEL TREBBIO ..................27 ant aspects of the art and underworld scenes, essential events, by Matt Riggsby and adventure ideas for three different eras. Then get help with creating citizens suitable for the period, including a new MAP OF VILLA GROUNDS...............29 GURPS template. During the Cold War, the front line for the commingling FLOOR PLANS OF THE VILLA ............30 of spies, dissidents, and ideologues was East Berlin. Tour landmarks, keep your nose clean amid the daily life, and dis- REVOLUTIONARY CUBA ................33 cover important government organizations. It includes a City by Nathan Milner Stats overview, offers a brief history of the rise and fall of the famous wall, and has suggestions for adding it to your cam- FURBO VENEZIA.....................37 paign, with ideas for espionage, cyberpunk, and more. by Matt Riggsby There will always be Hot Spots . even in the future of Transhuman Space! Revisit this setting with its cre- RANDOM THOUGHT TABLE..............38 by Steven Marsh, Pyramid Editor ator David L. -

Domenico Ghirlandaio 1 Domenico Ghirlandaio

Domenico Ghirlandaio 1 Domenico Ghirlandaio Domenico Ghirlandaio Supposed self-portrait, from Adoration of the Magi, 1488 Birth name Domenico di Tommaso Curradi di Doffo Bigordi Born 11 January 1449Florence, Italy Died 11 January 1494 (aged 45)Florence, Italy (buried in the church of Santa Maria Novella) Nationality Italian Field Painter Movement Italian Renaissance Works Paintings in: Church of Ognissanti, Palazzo Vecchio, Santa Trinita, Tornabuoni Chapel in Florence and Sistine Chapel, Rome Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449 – 11 January 1494) was an Italian Renaissance painter from Florence. Among his many apprentices was Michelangelo. Biography Early years Ghirlandaio's full name is given as Domenico di Tommaso di Currado di Doffo Bigordi. The occupation of his father Tommaso Bigordi and his uncle Antonio in 1451 was given as "'setaiuolo a minuto,' that is, dealers of silks and related objects in small quantities." He was the eldest of six children born to Tommaso Bigordi by his first wife Mona Antonia; of these, only Domenico and his brothers and collaborators Davide and Benedetto survived childhood. Tommaso had two more children by his second wife, also named Antonia, whom he married in 1464. Domenico's half-sister Alessandra (b. 1475) married the painter Bastiano Mainardi in 1494.[1] Domenico was at first apprenticed to a jeweller or a goldsmith, most likely his own father. The nickname "Il Ghirlandaio" (garland-maker) came to Domenico from his father, a goldsmith who was famed for creating the metallic garland-like necklaces worn by Florentine women. In his father's shop, Domenico is said to have made portraits of the passers-by, and he was eventually apprenticed to Alessio Baldovinetti to study painting and mosaic. -

J. M. Dent and Sons (London: 1909- ) J

J. M. Dent and Sons (London: 1909- ) J. M. Dent and Company (London: 1888-1909) ~ J. M. Dent and Sons has published an impres sive list of books by contemporary authors, but it made its mark on publishing history with its inex pensive series of classic literature. Everyman's Li brary in particular stands as a monument to the firm. It was not the first attempt at a cheap uni form edition of the "great books," but no similar series except Penguin Books has ever exceeded it in scope, and none without exception has ever matched the high production standards of the early Everyman volumes. Joseph Malaby Dent, born on 30 August 1849, was one of a dozen children of a Darling ton housepainter. He acquired his love of litera ture from the autodidact culture that flourished among Victorian artisans and shopkeepers. Dent attended a "Mutual Improvement Society" at a local chapel, where he undertook to write a paper on Samuel Johnson. Reading James Boswell's biography of Johnson, he was aston ished that the great men of the period-such as Edmund Burke, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Oliver Goldsmith-"should bow down before this old Juggernaut and allow him to walk over them, in sult them, blaze out at them and treat them as if they were his inferiors . At last it dawned on me that it was not the ponderous, clumsy, dirty old man that they worshipped, but the scholar ship for which he stood." Boswell's The Life of Sam uel Johnson, LL.D. ( 1791) taught Dent that "there JosephMa/,alry Dent (photographlry Frederick H. -

Toscana Patrimonio Dell'umanità Alla Scoperta Dei Siti Unesco

Toscana info: www.toscanapatrimoniomondiale.it www.visittuscany.com Patrimonio www.villegiardinimedicei.it dell’Umanità alla scoperta dei siti Unesco [ [Toscana Patrimonio dell’Umanità In Toscana natura, cultura, patrimonio artistico Centro Storico di Firenze e storico si compenetrano da secoli. Piazza del Duomo di Pisa Una ricchezza dall’eccezionale valore universale Centro Storico di San Gimignano riconosciuta dall’UNESCO con 8 siti Patrimonio Centro Storico di Siena Mondiale. Centro Storico di Pienza Luoghi che preservano bellezza artistica Val d’Orcia [ e paesaggistica, conservano vivida la memoria Le foreste primordiali dei faggi dei Carpazi e di altre regioni d’Europa del passato che diventano un’insostituibile fonte di vita della cultura contemporanea e di ispirazione Ville e Giardini medicei in Toscana Villa medicea di Artimino per le future generazioni. Giardino di Boboli Luoghi da conoscere e visitare senza fretta, Villa medicea di Cafaggiolo Villa medicea di Careggi apprezzandone i valori, da sempre amati da artisti Giardino della villa di Castello ed intellettuali che in questa terra hanno viaggiato Villa medicea di Cerreto Guidi Villa Medici a Fiesole e vissuto. Villa medicea La Màgia [ Villa medicea della Petraia Un’eredità culturale per tutta l’umanità presentata Villa medicea del Poggio Imperiale anche attraverso lo sguardo e le parole Giardino di Pratolino Villa medicea di Poggio a Caiano di grandi autori che hanno saputo cogliere l’essenza Palazzo mediceo di Seravezza dei piccoli borghi, le atmosfere delle città e la bellezza Castello del Trebbio della natura. È questo che la Toscana vi invita a scoprire, gustare, proteggere ed amare. www.toscanapatrimoniomondiale.it L’UNESCO, nata a Parigi il 4 novembre 1945, è l’organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite che si occupa di cultura, istruzione, scienze e arti. -

Validation of a Parametric Approach for 3D Fortification Modelling: Application to Scale Models

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W1, 2013 3D-ARCH 2013 - 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25 – 26 February 2013, Trento, Italy VALIDATION OF A PARAMETRIC APPROACH FOR 3D FORTIFICATION MODELLING: APPLICATION TO SCALE MODELS K. Jacquot, C. Chevrier, G. Halin MAP-Crai (UMR 3495 CNRSMCC), ENSA Nancy, 54000 Nancy, France (jacquot, chevrier, halin)@crai.archi.fr Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: architectural heritage, bastioned fortifications, parametric modelling, knowledge based, scale model, 3D surveys ABSTRACT: Parametric modelling approach applied to cultural heritage virtual representation is a field of research explored for years since it can address many limitations of digitising tools. For example, essential historical sources for fortification virtual reconstructions like plans-reliefs have several shortcomings when they are scanned. To overcome those problems, knowledge based-modelling can be used: knowledge models based on the analysis of theoretical literature of a specific domain such as bastioned fortification treatises can be the cornerstone of the creation of a parametric library of fortification components. Implemented in Grasshopper, these components are manually adjusted on the data available (i.e. 3D surveys of plans-reliefs or scanned maps). Most of the fortification area is now modelled and the question of accuracy assessment is raised. A specific method is used to evaluate the accuracy of the parametric components. The results of the assessment process will allow us to validate the parametric approach. The automation of the adjustment process can finally be planned. The virtual model of fortification is part of a larger project aimed at valorising and diffusing a very unique cultural heritage item: the collection of plans-reliefs. -

Defending Scilly

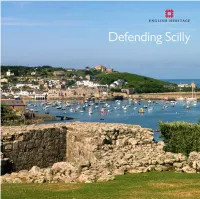

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Celebrating the City: the Image of Florence As Shaped Through the Arts

“Nothing more beautiful or wonderful than Florence can be found anywhere in the world.” - Leonardo Bruni, “Panegyric to the City of Florence” (1403) “I was in a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence.” - Stendahl, Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio (1817) “Historic Florence is an incubus on its present population.” - Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence (1956) “It’s hard for other people to realize just how easily we Florentines live with the past in our hearts and minds because it surrounds us in a very real way. To most people, the Renaissance is a few paintings on a gallery wall; to us it is more than an environment - it’s an entire culture, a way of life.” - Franco Zeffirelli Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 Celebrating the City, page 2 Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 The citizens of renaissance Florence proclaimed the power, wealth and piety of their city through the arts, and left a rich cultural heritage that still surrounds Florence with a unique and compelling mystique. This course will examine the circumstances that fostered such a flowering of the arts, the works that were particularly created to promote the status and beauty of the city, and the reaction of past and present Florentines to their extraordinary home. In keeping with the ACM Florence program‟s goal of helping students to “read a city”, we will frequently use site visits as our classroom.