Negation in Kambaata (Cushitic) Yvonne Treis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi Smriti Singh1, Om P. Damani2, Vaijayanthi M. Sarma2 (1) Insideview Technologies (India) Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad (2) Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We present algorithms for identifying Hindi Noun Groups and Verb Groups in a given text by using morphotactical constraints and sequencing that apply to the constituents of these groups. We provide a detailed repertoire of the grammatical categories and their markers and an account of their arrangement. The main motivation behind this work on word group identification is to improve the Hindi POS Tagger’s performance by including strictly contextual rules. Our experiments show that the introduction of group identification rules results in improved accuracy of the tagger and in the resolution of several POS ambiguities. The analysis and implementation methods discussed here can be applied straightforwardly to other Indian languages. The linguistic features exploited here are drawn from a range of well-understood grammatical features and are not peculiar to Hindi alone. KEYWORDS : POS tagging, chunking, noun group, verb group. Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Papers, pages 2491–2506, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 2491 1 Introduction Chunking (local word grouping) is often employed to reduce the computational effort at the level of parsing by assigning partial structure to a sentence. A typical chunk, as defined by Abney (1994:257) consists of a single content word surrounded by a constellation of function words, matching a fixed template. Chunks, in computational terms are considered the truncated versions of typical phrase-structure grammar phrases that do not include arguments or adjuncts (Grover and Tobin 2006). -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

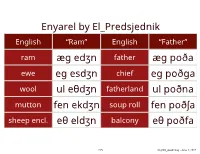

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So What’S New About Them? Author(S): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38Th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), Pp

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them? Author(s): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), pp. 47-62 General Session and Thematic Session on Language Contact Editors: Kayla Carpenter, Oana David, Florian Lionnet, Christine Sheil, Tammy Stark, Vivian Wauters Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/ . The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage , the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them?1 TRIDHA CHATTERJEE University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Introduction In this paper I describe bilingual complex verb constructions in Bengali-English bilingual speech. Bilingual complex verbs have been shown to consist of two parts, the first element being either a verbal or nominal element from the non- native language of the bilingual speaker and the second element being a helping verb or dummy verb from the native language of the bilingual speaker. The verbal or nominal element from the non-native language provides semantics to the construction and the helping verb of the native language bears inflections of tense, person, number, aspect (Romaine 1986, Muysken 2000, Backus 1996, Annamalai 1971, 1989). I describe a type of Bengali-English bilingual complex verb which is different from the bilingual complex verbs that have been shown to occur in other codeswitched Indian varieties. I show that besides having a two-word complex verb, as has been shown in the literature so far, bilingual complex verbs of Bengali-English also have a three-part construction where the third element is a verb that adds to the meaning of these constructions and affects their aktionsart (aspectual properties). -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Designing a Rule Based Stemming Algorithm for Kambaata Language Text

Jonathan Samuel & Solomon Teferra Designing A Rule Based Stemming Algorithm for Kambaata Language Text Jonathan Samuel [email protected] Telecom Excellence Academy/ Digital Learning Ethio Telecom Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Solomon Teferra [email protected] Faculty of Informatics/ School of Information Science Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Abstract Stemming is the process of reducing inflectional and derivational variants of a word to its stem. It has substantial importance in several natural language processing applications. In this research, a rule based stemming algorithm that conflates Kambaata word variants has been designed for the first time. The algorithm is a single pass, context-sensitive, and longest-matching designed by adapting rule-based stemming approach. Several studies agree that Kambaata is strictly suffixing language with a rich morphology and word formations mostly relying on suffixation; even though its word formation involves infixation, compounding, blending and reduplication as well. The output of this study is a context-sensitive, longest-match stemming algorithm for Kambaata words. To evaluate the stemmer’s effectiveness, error counting method was applied. A test set of 2425 distinct words was used to evaluate the stemmer. The output from the stemmer indicates that out of 2425 words, 2349 words (96.87%) were stemmed correctly, 63 words (2.60%) were over stemmed and 13 words (0.54%) were under stemmed. What is more, a dictionary reduction of 65.86% has also been achieved during evaluation. The main factor for errors in stemming Kambaata words is the language’s rich and complex morphology. Hence several errors can be corrected by exploring more rules. -

Similative Morphemes As Purpose Clause Markers in Ethiopia and Beyond Yvonne Treis

Similative morphemes as purpose clause markers in Ethiopia and beyond Yvonne Treis To cite this version: Yvonne Treis. Similative morphemes as purpose clause markers in Ethiopia and beyond. Yvonne Treis; Martine Vanhove. Similative and Equative Constructions: A cross-linguistic perspective, 117, John Benjamins, pp.91-142, 2017, Typological Studies in Language, ISBN 9789027206985. hal-01351924 HAL Id: hal-01351924 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01351924 Submitted on 4 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Similative morphemes as purpose clause markers in Ethiopia and beyond Yvonne Treis LLACAN (CNRS, INALCO, Université Sorbonne Paris-Cité) Abstract In more than 30 languages spoken at the Horn of Africa, a similative morpheme ‘like’ or a noun ‘manner’ or ‘type’ is used as a marker of purpose clauses. The paper first elaborates on the many functions of the enclitic morpheme =g ‘manner’ in Kambaata (Highland East Cushitic), which is used, among others, as a marker of the standard in similative and equative comparison (‘like’, ‘as’), of temporal clauses of immediate anteriority (‘as soon as’), of complement clauses (‘that’) and, most notably, of purpose clauses (‘in order to’). -

Polysemous Agent Nominals in Kambaata (Cushitic)*

Author manuscript, published in "Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 64, 4 (2011) 369-381" Published 2011in: Luschützky, Hans-Christian & Franz Rainer (eds.) 2011. Agent-noun polysemy in a cross-linguistic perspective. Special issue of Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 64, 4: 369-381 [This is a pre-publication version. Please quote the final published version.] YVONNE TREIS (La Trobe University) Polysemous Agent Nominals in Kambaata (Cushitic)* Kambaata has a morpheme -aan with which agent nominals can be derived from verbs and nouns. The present article discusses, firstly, the morphological and syntactic characteristics of -aan nominals and the specific problem of which word class they should be assigned to. Secondly, it is shown that the -aan morpheme is multifunctional. Apart from agent nominals, it is used to derive instrument, place and patient nominals. 1. Introduction Kambaata belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language phylum, more precisely to the Highland East Cushitic (HEC) language group. The hitherto little documented language is spoken by more than 600,000 speakers in an area approximately 300 km south-west of the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa. The lan- guage has a robust noun-verb distinction and a (sub-)word class of adjectives.1 Kambaata is strictly suffixing and has a rich verbal and nominal morphology. One of its derivational morphemes, the agentive morpheme -aan, productively gener- ates agent nominals on the basis of verbs. In the present article, the formal features (section 2) as well as the meaning and use of -aan nominals (section 3) are dis- cussed. In a language without a documented history, agent nominals can only be analysed in a synchronic perspective.2 The present work is intended to supplement the vast literature on agentive derivations that is predominantly concerned with Indo-European languages. -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89 -

Declension of Nouns

DECLENSION OF NOUNS In English, the relationship between words in a sentence depends primarily on word order. The difference between the god desires the girl and the girl desires the god is immediately apparent to us. Latin does not depend on word order for basic meaning, but on inflections (changes in the endings of words) to indicate the function of words within a sentence. Thus the god desires the girl can be expressed in Latin deus puellam desiderat, puellam deus desiderat, or desiderat puellam deus without any change in basic meaning. The accusative ending of puellam shows that the girl is being acted upon (i.e., is the object of the verb) and is not the actor (i.e., the subject of the verb). Similarly, the nominative form of deus shows that the god is the actor (agent) in the sentence, not the object of the verb. The inflection of nouns is called declension. The individual declensions are called cases, and together they form the case system. Nouns, pronouns, adjectives and participles are declined in six Cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and vocative and two Numbers (singular and plural). (The locative, an archaic case, existed in the classical period only for a few words). Nominative Indicates the subject of a sentence. (The boy loves the book). Genitive Indicates possession. (The boy loves the girl’s book). Dative Indicates indirect object. (The boy gave the book to the girl). Accusative Indicates direct object. (The boy loves the book). Ablative Answers the questions from where? by what means? how? from what cause? in what manner? when? or where? The ablative is used to show separation (from), instrumentality or means (by, with), accompaniment (with), or locality (at).