The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 12 Web Master.Txt

Student name Sex City County State Country Level High School Honor Roll Abbott, Logan M Wichita SG KS USA Junior Maize High School School of Pharmacy Abbott, Taylor F Lawrence DG KS USA Junior Lawrence High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abdouch, Macrina F Omaha NE USA Senior Millard North High School School of Architecture, Design and Planning Abel, Hilary F Wakefield CY KS USA Freshman Junction City Senior High Sch College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abi, Binu F Olathe JO KS USA Prof 1 Olathe South High School School of Pharmacy Ablah, George M Wichita SG KS USA Junior Andover High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Ablah, Patricia F Wichita SG KS USA Sophomore Andover High School School of Business Abraham, Christopher M Overland Park JO KS USA Freshman Blue Valley Northwest High Sch College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abrahams, Brandi F Silver Lake SN KS USA Freshman Silver Lake Jr/Sr High School School of Business Absher, Cassie F Eudora DO KS USA Senior College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Abshire, Christopher M Overland Park JO KS USA Sophomore Blue Valley High School School of Engineering Acharya, Birat M Olathe JO KS USA Junior Olathe East High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Acosta Caballero, Andrea F Asuncion PRY Senior College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Adair, Sarah F Olathe JO KS USA Junior Olathe South High School College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Adams, Caitlin F Woodridge IL USA Freshman South HS in Downer's Grove College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Adams, Nancy F Lees Summit MO USA Senior Blue Springs -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

Construction of Hong-Dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics

Universität Bielefeld Fakultät für Soziologie Construction of Hong-dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics Dissertation Zur Erlangung eines Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Soziologie der Universität Bielefeld Mihye Cho 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jörg Bergmann Bielefeld Juli 2007 ii Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research Questions 4 1.2 Theoretical and Analytical Concepts of Research 9 1.3 Research Strategies 13 1.3.1 Research Phase 13 1.3.2 Data Collection Methods 14 1.3.3 Data Analysis 19 1.4 Structure of Research 22 Chapter 2 ‘Hong-dae Culture’ and Ambiguous Meanings of ‘the Cultural’ 23 2.1 Hong-dae Scene as Hong-dae Culture 25 2.2 Top 5 Sites as Representation of Hong-dae Culture 36 2.2.1 Site 1: Dance Clubs 37 2.2.2 Site 2: Live Clubs 47 2.2.3 Site 3: Street Hawkers 52 2.2.4 Site 4: Streets of Style 57 2.2.5 Site 5: Cafés and Restaurants 61 2.2.6 Creation of Hong-dae Culture through Discourse and Performance 65 2.3 Dualistic Approach of Authorities towards Hong-dae Culture 67 2.4 Concluding Remarks 75 Chapter 3 ‘Cultural District’ as a Transitional Cultural Policy in Paradigm Shift 76 3.1 Dispute over Cultural District in Hong-dae area 77 3.2 A Paradigm Shift in Korean Cultural Policy: from Preserving Culture to 79 Creating ‘the Cultural’ 3.3 Cultural District as a Transitional Cultural Policy 88 3.3.1 Terms and Objectives of Cultural District 88 3.3.2 Problematic Issues of Cultural District 93 3.4 Concluding Remarks 96 Chapter -

The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present

Article The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present Mohamed Elaskary Department of Arabic Interpretation, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul 17035, South Korea; [email protected]; Tel. +821054312809 Received: 01 October 2018; Accepted: 22 October 2018; Published: 25 October 2018 Abstract: The Korean Wave—otherwise known as Hallyu or Neo-Hallyu—has a particularly strong influence on the Middle East but scholarly attention has not reflected this occurrence. In this article I provide a brief history of Hallyu, noting its mix of cultural and economic characteristics, and then analyse the reception of the phenomenon in the Arab Middle East by considering fan activity on social media platforms. I then conclude by discussing the cultural, political and economic benefits of Hallyu to Korea and indeed the wider world. For the sake of convenience, I will be using the term Hallyu (or Neo-Hallyu) rather than the Korean Wave throughout my paper. Keywords: Hallyu; Korean Wave; K-drama; K-pop; media; Middle East; “Gangnam Style”; Psy; Turkish drama 1. Introduction My first encounter with Korean culture was in 2010 when I was invited to present a paper at a conference on the Korean Wave that was held in Seoul in October 2010. In that presentation, I highlighted that Korean drama had been well received in the Arab world because most Korean drama themes (social, historical and familial) appeal to Arab viewers. In addition, the lack of nudity in these dramas as opposed to that of Western dramas made them more appealing to Arab viewers. The number of research papers and books focused on Hallyu at that time was minimal. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

Daughter Album If You Leave M4a Download Download Verschillende Artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album

daughter album if you leave m4a download Download Verschillende artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album. 1. It's My Life 2. From the Underworld 3. Bring a Little Lovin' 4. Do Wah Diddy Diddy 5. The Walls Fell Down 6. Summer Nights 7. Tuesday Afternoon 8. A World Without Love 9. Downtown 10. This Strange Effect 11. Homburg 12. Eloise 13. Tin Soldier 14. Somebody Help Me 15. I Can't Control Myself 16. Turquoise 17. For Your Love 18. It's Five O'Clock 19. Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter 20. Rain On the Roof 21. Mama 22. Can I Get There By Candlelight 23. You Were On My Mind 24. Mellow Yellow 25. Wishin' and Hopin' 26. Albatross 27. Seasons In the Sun 28. My Mind's Eye 29. Do You Want To Know a Secret? 30. Pretty Flamingo 31. Come and Stay With Me 32. Reflections of My Life 33. Question 34. The Legend of Xanadu 35. Bend It 36. Fire Brigade 37. Callow La Vita 38. Goodbye My Love 39. I'm Alive 40. Keep On Running 41. The Hippy Hippy Shake 42. It's Not Unusual 43. Love Is All Around 44. Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood 45. The Days of Pearly Spencer 46. The Pied Piper 47. With a Girl Like You 48. Zabadak! 49. I Only Want To Be With You 50. Here It Comes Again 51. Don't Let the Sun Catch You Crying 52. Have I the Right 53. Darling Be Home Soon 54. Only One Woman 55. -

K-Pop Fandom in Lima,Perú

Wesleyan ♦ University K-POP FANDOM IN LIMA, PERÚ: VIRTUAL AND LIVE CIRCULATION PATTERNS By Stephanie Ho Faculty Advisor: Dr. Mark Slobin A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Middletown, Connecticut MAY 2015 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mark Slobin, for his invaluable guidance and insights during the process of writing this thesis. I am also immensely grateful to Dr. Su Zheng and Dr. Matthew Tremé for acting as members of my thesis committee and for their considered thoughts and comments on my early draft, which contributed greatly to the improvement of my work. I would also like to thank Gabrielle Misiewicz for her help with editing this thesis in its final stages, and most importantly for supporting me throughout our time together as classmates and friends. I thank the Peruvian fans that took the time to help me with my research, as well as Virginia and Violeta Chonn, who accompanied me on fieldwork visits and took the time to share their opinions with me regarding the Limeñan fandom. Thanks to my friends and colleagues at Wesleyan – especially Nicole Arulanantham, Gen Conte, Maho Ishiguro, Ellen Lueck, Joy Lu, and Ender Terwilliger – as well as Deb Shore from the Music Department, and Prof. Ann Wightman of the Latin American Studies Department. From my pre-Wesleyan life, I would like to acknowledge Francesca Zaccone, who introduced me to K-pop in 2009, and has always been up for discussing the K-pop world with me, be it for fun or for the purpose of helping me further my analyses. -

Cultural Production in Transnational Culture: an Analysis of Cultural Creators in the Korean Wave

International Journal of Communication 15(2021), 1810–1835 1932–8036/20210005 Cultural Production in Transnational Culture: An Analysis of Cultural Creators in the Korean Wave DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada By employing cultural production approaches in conjunction with the global cultural economy, this article attempts to determine the primary characteristics of the rapid growth of local cultural industries and the global penetration of Korean cultural content. It documents major creators and their products that are received in many countries to identify who they are and what the major cultural products are. It also investigates power relations between cultural creators and the surrounding sociocultural and political milieu, discussing how cultural creators develop local popular culture toward the global cultural markets. I found that cultural creators emphasize the importance of cultural identity to appeal to global audiences as well as local audiences instead of emphasizing solely hybridization. Keywords: cultural production, Hallyu, cultural creators, transnational culture Since the early 2010s, the Korean Wave (Hallyu in Korean) has become globally popular, and media scholars (Han, 2017; T. J. Yoon & Kang, 2017) have paid attention to the recent growth of Hallyu in many parts of the world. Although the influence of Western culture has continued in the Korean cultural market as well as elsewhere, local cultural industries have expanded the exportation of their popular culture to several regions in both the Global South and the Global North. Social media have especially played a major role in disseminating Korean culture (Huang, 2017; Jin & Yoon, 2016), and Korean popular culture is arguably reaching almost every corner of the world. -

Hyeri Still Dating

Jun 20, · Fans are happy to hear that the couple is still going strong. There had been breakup rumors previously, but Ryu Joon Yeol and Hyeri just proved fans that their love is still the same and they’re still dating. The couple met on the set of “Reply ” and went public with their relationship in . Jun 20, · Not sure why they need to report a couple on a date but glad to hear they're still dating well." Ryu Jun-yeol and Hyeri worked together in the tvN . Dispatch Translation: “Girl’s Day Hyeri and Ryu Jun Yeol are officially in a relationship, according to Dispatch and their exclusive photos. Dispatch Translation: “A common couple by the lake.” Dispatch captured the two on a date in March , at Seokchon Lake. The lake is a popular date spot, especially during Cherry Blossom season. Aug 16, · New celebrity couple alert! On August 16, Ryu Jun Yeol’s agency C- JeS Entertainment confirmed the reports that the actor is dating Girl’s Day’s Hyeri and stated, “Ryu Jun Yeol and Hyeri. Nov 18, · The two stars have been dating publicly since August of Hyeri began, "Even though we're both busy, we're still seeing each other well. I see my [Girl's Day] members and my boyfriend on an. Nov 20, · Hyeri was only natural in AM cause that character was tailor made for her as it’s very close to her real life personality. It’s super cute how she’s still dating . Jun 20, · Ryu Joon Yeol and Hyeri first met when they worked together in tvN’s Reply , which aired in , and started dating publicly since August of Rumors of their breakup have been surfaced a few times, but the two have dismissed these rumors by saying that they are still . -

URL 100% (Korea)

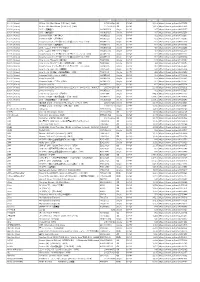

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Lirik Lagu Because I Miss You Dan Artinya

Lirik Lagu Because I Miss You Dan Artinya I tell myself that I can forget you. I pretended that I did and tried laughing. As if it's nothing, I went to the movies alone. In order to fill up your empty seat. If I miss. Lirik Dan Arti Lagu I Miss You Ost My Lovely Girl: Lirik Dan Arti Lagu I Miss You Ost My Lovely Girl news, Lirik Dan Arti Lagu I Miss You Ost My Lovely Girl. "Geudaega geuriweoseo" which means because I miss you. I am not sure about the lyrics and "bogopa" I don't know if it means I miss you or I want to see you. But I'ma miss you so much. I'm too You deserve the world and soon the world's gon' come around Because you know I'm all about that bass, 'Bout that bass, no treble I'm all 'bout that bass, 'bout that bass, no. Kalau dulu kita tak bertemu Takkan pernah ku rasakan arti rindu Kalau dulu kita tak kenal Takkan pernah ku. Its when you miss someone, because its been so had to forget them, and you've hoped that your feelings have could change but it doesn't, insted you carry. Lirik Dizi Müziği Dan Artinya, Free Download Mp3 Video Music. Heartstrings Because I miss you Lyrics. Download Play. Lirik Lagu Because I Miss You Dan Artinya >>>CLICK HERE<<< Lirik lagu Kim Tae Woo (g.o.d) Only You My Lovely Girl OST dan Terjemahannya indonesia english romanized hangul. Terjemahannya dalam arti bahasa indonesia.