Download Slideshow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance

CLR-Nº 6 17/6/08 15:15 Página 85 CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 ˙ VOL VI \ 2008, pp. 85-99 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance PAULINE BROOKS LIVERPOOL JOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT: This article discusses the dance performance project Interface 2, which involved live dancers, animated computer projections (remediated creations of the live section), and the interface of live dancers with dancers on film. It analyses the responses and perceptions of an audience to the changing transformations of the media and the staging of the dance performance. Alongside these responses, I compare and contrast some of the philosophical and aesthetic debates from the past three decades regarding dance and technology in performance, including that of the tension between the acceptance or rejection of «unnatural» remediated bodies and «natural» live bodies moving in the stage space. Keywords: Dance, Remediation, Live, Film, Computer animated. RESUMEN: Este artículo aborda el proyecto de danza Interface 2, que agrupaba bailarines en directo, proyecciones animadas por ordenador (creaciones transducidas de la sección en vivo) y la interfaz de bailarines en vivo con bailarines filmados. Se analizan la respuesta y percepciones del público hacia las transformaciones continuas de los medios tecnológicos de la puesta en escena de la danza. Igualmente, se comparan y contrastan algunos de los debates filosóficos y estéticos de las últimas tres décadas en relación con la danza y el uso de la tecnología en la representación, en particular el referente a la tensión entre la aceptación o rechazo de la falta de «naturalidad» de los cuerpos transducidos y la «naturalidad» de los cuerpos en vivo moviéndose por el espacio escénico. -

MASSEY Dave Slreport S17

Parts II-V Sabbatical Leave Report II. Re-statement of Sabbatical Leave Application The intention behind this sabbatical proposal is to study contemporary dance forms from internationally and nationally recognized artists in Israel, Europe, and the U.S. The plan is to take daily dance class, week long workshops, to observe dance class and company rehearsals, and interview directors, choreographers, and artists to gain further insight into their movement creation process. This study will benefit my teaching, choreographic awareness, and movement research, which will benefit my students and my department as courses are enhanced by new methodologies, techniques and strategies. The second part of this plan is to visit California colleges and universities to investigate how contemporary dance is being built into their curriculum. Creating a dialogue with my colleagues about this developing dance genre will be important as my department implements contemporary dance into its curriculum. The third part of the sabbatical is to co-produce a dance concert in the San Diego area showcasing choreography that has been created using some of the new methodologies, techniques and strategies founded and discussed while on sabbatical. I will document all hours in a spreadsheet submitted with my sabbatical report. I estimate 580 hours. III. Completion of Objectives, Description of Activities Objective #1: a. To explore, learn, and document best practices in Contemporary Dance b. I started my sabbatical researching contemporary dance and movement. I scoured the web for journals, magazines, videos that gave me insight into how people in dance were talking about this contemporary genre. I also read several books that were thought-provoking about contemporary movement, training and the contemporary dancer. -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Music, Dance and Swans the Influence Music Has on Two Choreographies of the Scene Pas D’Action (Act

Music, Dance and Swans The influence music has on two choreographies of the scene Pas d’action (Act. 2 No. 13-V) from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake Naam: Roselinde Wijnands Studentnummer: 5546036 BA Muziekwetenschap BA Eindwerkstuk, MU3V14004 Studiejaar 2017-2018, block 4 Begeleider: dr. Rebekah Ahrendt Deadline: June 15, 2018 Universiteit Utrecht 1 Abstract The relationship between music and dance has often been analysed, but this is usually done from the perspective of the discipline of either music or dance. Choreomusicology, the study of the relationship between dance and music, emerged as the field that studies works from both point of views. Choreographers usually choreograph the dance after the music is composed. Therefore, the music has taken the natural place of dominance above the choreography and can be said to influence the choreography. This research examines the influence that the music has on two choreographies of Pas d’action (act. 2 no. 13-V), one choreographed by Lev Ivanov, the other choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev from the ballet Swan Lake composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by conducting a choreomusicological analysis. A brief history of the field of choreomusicology is described before conducting the analyses. Central to these analyses are the important music and choreography accents, aligning dance steps alongside with musical analysis. Examples of the similarities and differences between the relationship between music and dance of the two choreographies are given. The influence music has on these choreographies will be discussed. The results are that in both the analyses an influence is seen in the way the choreography is built to the music and often follows the music rhythmically. -

Library of Congress Collection Overviews: Dance

COLLECTION OVERVIEW DANCE I. SCOPE This overview focuses on dance materials found throughout the Library’s general book collection as well as in the various special collections and special format divisions, including General Collections; the Music Division; Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound; the American Folklife Center; Manuscript Division; Prints & Photographs; and Rare Book and Special Collections. The overview also identifies dance- related Internet sources created by the Library as well as subscription databases. II. SIZE Dance materials can be found in the following classes: BJ; GT; VN; GV; M; and ML. All classes, when totaled, add up to 57,430 dance and dance-related items. Class GV1580- 1799.4 (Dancing) contains 10,114 items, constituting the largest class. The Music Division holds thirty special collections of dance materials and an additional two hundred special collections in music and theater that include dance research materials. III. GENERAL RESEARCH STRENGTHS General research strengths in the area of dance research at the Library of Congress fall within three areas: (A) dance instructional and etiquette manuals, especially those printed between 1520 and 1920, (B) dance on camera, and (C) folk, traditional, and ethnic dance. A. The first primary research strength of the Library of Congress is its collections of 16th-20th-century dance instructional and etiquette manuals and ancillary research materials, which are located in the General Collections, Music Division, and Rare Book and Special Collections (sub-classifications GN, GT, GV, BJ, and M). Special Collections within the Music Division that compliment this research are numerous, including its massive collection of sheet music from the early 1800s through the 20th century. -

Exegesis for Phd in Creative Practice SVEBOR SEČAK Shakespeare's Hamlet in Ballet—A Neoclassical and Postmodern Contemporary Approach

Exegesis for PhD in Creative Practice SVEBOR SEČAK Shakespeare's Hamlet in Ballet—A Neoclassical and Postmodern Contemporary Approach INTRODUCTION In this exegesis I present my PhD project which shows the transformation from a recording of a neoclassical ballet performance Hamlet into a post-postmodern artistic dance video Hamlet Revisited. I decided to turn to my own choreography of the ballet Hamlet which premiered at the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb in 2004, in order to revise it with a goal to demonstrate the neoclassical and the contemporary postmodern approach, following the research question: How to transform an archival recording of a neoclassical ballet performance into a new artistic dance video by implementing postmodern philosophical concepts? This project is a result of my own individual transformations from a principal dancer who choreographs the leading role for himself, into a more self-reflective mature artist as a result of aging, the socio-political changes occurring in my working and living environment, and my academic achievements, which have exposed me to the latest philosophical and theoretical approaches. Its significance lies in establishing communication between neoclassical and postmodern approaches, resulting in a contemporary post-postmodern artistic work that elucidates the process in the artist's mind during the creative practice. It complements my artistic and scholarly work and is an extension built on my previous achievements implementing new comprehensions. As a life-long ballet soloist and choreographer my area of interest is the performing arts, primarily ballet and dance and the dualism between the abstract and the narrative approaches 1 Exegesis for PhD in Creative Practice SVEBOR SEČAK Shakespeare's Hamlet in Ballet—A Neoclassical and Postmodern Contemporary Approach to ballet works1. -

The Evolution of Dance As a Storytelling Device in the Integrated Musical

Dance Speaks Where Words fail: the Evolution of Dance as a Storytelling Device in the Integrated Musical. In partial fulfilment of the requirements for Honours in Theatre and Drama Murdoch University by Ellin Sears 30881438 1 This thesis is presented for the Honours degree in Theatre and Drama Studies at Murdoch University, 2012. I, Ellin Sears, declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution. Information quoted or paraphrased from the work of others has been acknowledged in the footnotes and a full bibliography is provided at the end of this work Signed ……………………………… Date………………………………… 2 COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s51.2 of the Copyright Act 1968, all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such a reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: …………………………………………………………... Full Name of Degree: …………………………………………………………………... e.g. Bachelor of Science with Honours in Chemistry. Thesis Title: …………………………………………………………………... …………………………………………………………………... …………………………………………………………………... …………………………………………………………………... Author: …………………………………………………………………... Year: ………………………………………………………………....... 3 Contents: Abstract – p5 Acknowledgements – p6 Introduction and Literature Review – p7 Part One – Musicals and Analysis: An Ongoing Struggle – p10 - Genre Theory - Towards a Theory of Integration - Doubled Time: A New Critical Perspective? Part Two – Dance in the Integrated Musical: A Case Study – p17 Part Three – Commentary on Twelfth Night and Gesamtkunstwerk – p25 Appendices – p58 Bibliography – p77 4 ABSTRACT Musical Theatre has long suffered the stigma of being perceived as a low form of art by scholars and critics alike. -

Mattingly Final(Numbered)

Set in Motion: Dance Criticism and the Choreographic Apparatus By Kate Mattingly A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Abigail De Kosnik Professor Anton Kaes Professor SanSan Kwan Spring 2017 Copyright © Kate Mattingly All Rights Reserved Abstract Set in Motion: Dance Criticism and the Choreographic Apparatus By Kate Mattingly Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair This dissertation examines the multiple functions of dance criticism in the 20th and 21st centuries in the United States. I foreground institutional interdependencies that shape critics’ practices, as well as criticism’s role in approaches to dance-making, and the necessary and fraught relations between dance criticism and higher education. To challenge the pervasive image of the critic as evaluator and of criticism as definitive, Set in Motion focuses on conditions that produce and endorse certain forms of criticism, and in turn how this writing has gained traction. I employ the concept of a choreographic apparatus to show shifting relations amongst writers, artists, publications, readers, institutions, and audiences. Their interactions generate frameworks that influence dance’s history, canon, and disciplinary formations. I propose a way of situating criticism as a form of writing that intersects with, informs, and influences both history and theory. Set in Motion expands discourse on writing by examining the continuities and discontinuities in practices over the course of a century. -

The Return of Chinese Dance Socialist Continuity Post-Mao

5 The Return of Chinese Dance Socialist Continuity Post-Mao With its suppression of early socialist dance projects in favor of the newer form of revolutionary ballet, the Cultural Revolution decade of 1966–76 nearly brought an end to Chinese dance, as both an artistic project and a historical memory. Prior to the Cultural Revolution, Chinese dance had been the dominant concert dance form in the PRC. Most new dance choreography created between 1949 and 1965 had been in the genre of Chinese dance, and Chinese dance was the dance style officially promoted domestically and abroad as an expression of China’s socialist ideals and values. However, with the introduction of new cultural policies begin- ning in 1966, a decade of support for ballet and suppression of Chinese dance nearly wiped out memories of pre–Cultural Revolution activities in China’s dance field. Although many Chinese dance institutions that had been forced to shut down in 1966 reopened in the early 1970s, by the beginning of 1976 they were still banned from performing most pre–Cultural Revolution Chinese dance rep- ertoires, and ballet was still dominating the curriculum used to train new dancers. Dance films created before the Cultural Revolution were still censored from public view, meaning that most audiences had not seen pre–Cultural Revolution reper- toires, either live or on screen, for at least a decade. For children and adolescents too young to remember the pre–Cultural Revolution period, revolutionary ballet had become the only kind of socialist dance they knew. For them, revolutionary ballet was socialist dance. -

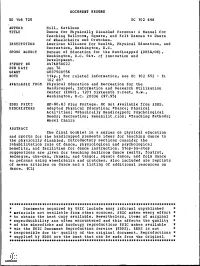

Dance for Physically Disabled Persons: a Manual for Teaching Ballroom, Square, and Folk Dances to Users of Wheelchairs and Crutches

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 146 720 EC 102 698 AUTHOR Hill, Kathleen TITLE Dance for Physically Disabled Persons: A Manual for Teaching Ballroom, Square, and Folk Dances to Users of Wheelchairs and Crutches. INSTITUTION American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Education for: the Handicapped (DHEW/OE), Washington, D.C. Div. cf Innovation and Development. MORT NO 447AH50022 PUB DATE Jun 76 GRANT G007500556 NOTE 114p.; For related information, see EC 102 692 - EL 102 697 AVAILABLE FROM Physical Education and Recreation for the Handicapped, Information and Research Utilization Center (IRUC), 1201 Sixteenth Sreet, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 ($7.95) EDRS PRICE ME-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adapted Physical Education; *Dance; Physical Acti-rities; *Physically Handicapped; Psychological Needs; Recreation; Rehabilit_tion; *Teaching Methods; Wheel Chairs ABSTRACT . The final booklet in a series on physical education and sports for the handicapped presents ideas for teaching dance to the physically disabled. Introductory sections consider the rehabilitation role of dance, physiological and psychological benefits, and facilities for dance instruction. Step-by-step suggestions are given for teaching ballroom dance (waltz, foxtrot, merengue, cha-cha, rhumta, and tango), square dance, and folk dance to persons using wheelchairs and crutches. Also included are reprints of seven articles on dance :and a listing of additional resources on dance. (CL) *********************************************************************** * Documents acquired by ERIC include many irformal unpublished * * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardccpy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). -

Creative Factors and Ethnic-Folk Dance: a Case Study of the Peacock Dance in China (1949-2013) by Jiaying You a Thesis Submitted

Creative Factors and Ethnic-folk Dance: A Case Study of the Peacock Dance in China (1949-2013) by Jiaying You A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ukrainian Folklore Departments of Modern Languages and Cultural Studies and Anthropology University of Alberta © Jiaying You, 2016 ii Abstract My dissertation topic focuses on the interaction between dances, their contexts, and their meanings. I am interested in a wide range of creative factors that are involved in the dance-context interaction. I chose to investigate these factors by looking at the Peacock Dance, which originates in the Dai culture. I write about eleven case studies and focus on four different creative factors that have changed the peacock dance - individual, community, nationality, and state. Creative factors are the factors that actively influence the form/context/meaning of an ethnic-folk dance in certain ways. I call these factors as “creative factors” because they influence the creation of new characteristics of the ethnic-folk dances. Various factors can influence change in ethnic-folk dances, and the ones I focus on are only four of many. Change in ethnic-folk dance usually happens under the influence of one or all four creative factors, though each factor may be more or less active. These case studies demonstrate how four creative factors have changed the peacock dance from the Dai ethnic group. Because of the absence of earlier detailed information, there is no original peacock dance to make comparisons in an absolute sense. I consider Dance #1, the peacock dance by Mao Xiang around 1949, as the “original” peacock dance in my dissertation.