Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond If you walk on and on, you get to your destination. If you question much, you get your information. If you do not sleep and idle, you preserve your life! (Maung Htin Aung 1959:87) So go the three lines of wisdom offered to the lazy student Maung Pauk Khaing in the well- known eponymous folk tale. A group of impoverished village youngsters, led by their teacher Daw Khin Thida, adapted the tale in 2007 in their first attempt to perform a play. From a well-to-do family that does not understand her philanthropic impulses, Khin Thida, an English teacher by profession, works at her free school in Insein, a suburb of Yangon (Rangoon) infamous for its prison. The shy students practiced first in Burmese for their village audience, and then in English for some foreign donors who were coming to visit the school. Khin Thida has also bought land in Bagan (Pagan) and is building a culture center there, hoping to attract the street children who currently pander to tourists at the site’s immense network of temples. TDR: The Drama Review 53:1 (T201) Spring 2009. ©2009 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 93 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram.2009.53.1.93 by guest on 02 October 2021 I first met Khin Thida in 2005 at NICA (Networking and Initiatives for Culture and the Arts), an independent nonprofit arts center founded in 2003 and run by Singaporean/Malaysian artists Jay Koh and Chu Yuan. -

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

An Analysis of the Religious Belief Characteristics of Southeast Asian Dance

2020 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Social Sciences & Humanities (SOSHU 2020) An Analysis of the Religious Belief Characteristics of Southeast Asian Dance Feirui Li Guangxi University For Nationalities, Guangxi, Nanning, 530006, China Keywords: Southeast asian dance, Religious beliefs, Thailand Abstract: The dances in Southeast Asia are colorful and can be divided into four major dance systems: Buddhism, Puppet, Hinduism and Islam. The four major dance systems are influenced by India's two epics. In some Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand and Vietnam, their religious culture is closely linked to dance arts. Strong religious culture permeates dance music, style and dance vocabulary. Based on the analysis of Southeast Asian dance art, this paper takes Thai dance art as an example to further elaborate its religious and cultural charm. 1. Introduction Engels said that religion, like philosophy, is a “higher, i.e. more far from the material economic foundation of ideology” [1]. However, as an ideology, it not only experienced the process of development and processing, but also developed independently according to its own laws. Religious culture and dance culture. Asean art, as a new breakthrough in Chinese art research, is very research-oriented [2]. Southeast Asia is made up of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia and other countries. Due to geographical and religious reasons, Southeast Asian countries represented by Indonesia, Thailand and Myanmar live alone in dance culture and are relatively developed [3]. Dances in Southeast Asia have strong religious color of Buddhism and Hinduism. As a result, the dance branches in Southeast Asia present four major dance departments, namely puppet dance department, Hindu dance department, Buddhist dance department and Islamic dance department. -

Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance

CLR-Nº 6 17/6/08 15:15 Página 85 CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 ˙ VOL VI \ 2008, pp. 85-99 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance PAULINE BROOKS LIVERPOOL JOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT: This article discusses the dance performance project Interface 2, which involved live dancers, animated computer projections (remediated creations of the live section), and the interface of live dancers with dancers on film. It analyses the responses and perceptions of an audience to the changing transformations of the media and the staging of the dance performance. Alongside these responses, I compare and contrast some of the philosophical and aesthetic debates from the past three decades regarding dance and technology in performance, including that of the tension between the acceptance or rejection of «unnatural» remediated bodies and «natural» live bodies moving in the stage space. Keywords: Dance, Remediation, Live, Film, Computer animated. RESUMEN: Este artículo aborda el proyecto de danza Interface 2, que agrupaba bailarines en directo, proyecciones animadas por ordenador (creaciones transducidas de la sección en vivo) y la interfaz de bailarines en vivo con bailarines filmados. Se analizan la respuesta y percepciones del público hacia las transformaciones continuas de los medios tecnológicos de la puesta en escena de la danza. Igualmente, se comparan y contrastan algunos de los debates filosóficos y estéticos de las últimas tres décadas en relación con la danza y el uso de la tecnología en la representación, en particular el referente a la tensión entre la aceptación o rechazo de la falta de «naturalidad» de los cuerpos transducidos y la «naturalidad» de los cuerpos en vivo moviéndose por el espacio escénico. -

Connecting Through Dance

Connecting Through Dance: The Multiplicity of Meanings of Kurdish Folk Dances in Turkey Mona Maria Nyberg Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the M.A. degree Department of Social Anthropology, University of Bergen Spring 2012 The front page photograph is taken by Mona Maria Nyberg at a Kurdish wedding celebration. The women who are dancing in the picture are not informants. II Acknowledgements While studying for an exam during my time as a bachelor student, I read a work by Professor Bruce Kapferer which made me reconsider my decision of not applying for the master program; I could write about dance, I realized. And now I have! The process has been challenging and intense, but well worth it. Throughout this journey I have been anything but alone on this, and the list of persons who have contributed is too long to mention. First of all I need to thank my informants. Without you this thesis could not have been written. Thank you for your help and generosity! Especially I want to thank everyone at the culture centers for allowing me do fieldwork and participate in activities. My inmost gratitude goes to two of my informants, whose names I cannot write out of reasons of anonymity - but you know who you are. I want to thank you for allowing me into your lives and making me part of your family. You have contributing to my fieldwork by helping me in in innumerous ways, being my translators – both in terms of language and culture. You have become two of my closest friends. -

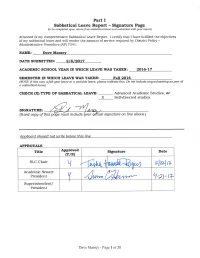

MASSEY Dave Slreport S17

Parts II-V Sabbatical Leave Report II. Re-statement of Sabbatical Leave Application The intention behind this sabbatical proposal is to study contemporary dance forms from internationally and nationally recognized artists in Israel, Europe, and the U.S. The plan is to take daily dance class, week long workshops, to observe dance class and company rehearsals, and interview directors, choreographers, and artists to gain further insight into their movement creation process. This study will benefit my teaching, choreographic awareness, and movement research, which will benefit my students and my department as courses are enhanced by new methodologies, techniques and strategies. The second part of this plan is to visit California colleges and universities to investigate how contemporary dance is being built into their curriculum. Creating a dialogue with my colleagues about this developing dance genre will be important as my department implements contemporary dance into its curriculum. The third part of the sabbatical is to co-produce a dance concert in the San Diego area showcasing choreography that has been created using some of the new methodologies, techniques and strategies founded and discussed while on sabbatical. I will document all hours in a spreadsheet submitted with my sabbatical report. I estimate 580 hours. III. Completion of Objectives, Description of Activities Objective #1: a. To explore, learn, and document best practices in Contemporary Dance b. I started my sabbatical researching contemporary dance and movement. I scoured the web for journals, magazines, videos that gave me insight into how people in dance were talking about this contemporary genre. I also read several books that were thought-provoking about contemporary movement, training and the contemporary dancer. -

The Intimate Connection of Rural and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Swarthmore College Works Spanish Faculty Works Spanish 2018 Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi Vila Swarthmore College, [email protected] P. Vila Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Julia Chindemi Vila and P. Vila. (2018). "Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century". Sound, Image, And National Imaginary In The Construction Of Latin/o American Identities. 39-90. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish/119 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 2 Another Look at the History of Tango The Intimate Connection of Rural ·and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi and Pablo Vila Since the late nineteenth century, popular music has actively participated in the formation of different identities in Argentine society, becoming a very relevant discourse in the production, not only of significant subjectivities, but also of emotional and affective agencies. In the imaginary of the majority of Argentines, the tango is identified as "music of the city," fundame ntally linked to the city of Buenos Aires and its neighborhoods. In this imaginary, the music of the capital of the country is distinguished from the music of the provinces (including the province of Buenos Aires), which has been called campera, musica criolla, native, folk music, etc. -

Circassian Customs & Traditions

Circassian Customs & Traditions АДЫГЭ ХАБЗЭ 1 Circassian Customs & Traditions Amjad M. Jaimoukha [compiler, editor, translator] АДЫГЭ ХАБЗЭ Жэмыхъуэ Амджэд (Амыщ) In English and Circassian (supplementary) Centre for Circassian Studies 2014 2 Circassian Customs & Traditions Circassian Culture & Folklore Second edition 2014 First published 2009 © 2014 Amjad Jaimoukha All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. 3 Contents Introduction 5 1. Birth 10 2. Christening 15 3. Upbringing 17 4. Courtship and Marriage 28 5. Divorce and Bigamy 62 6. ‘In sickness and in health’ 63 7. Death and Obsequies 70 8. Greetings and Salutes 80 9. The Circassian Code of Chivalry 83 • Respect for Women and Elders 84 • Blood-revenge 86 • Hospitality and Feasts 89 Appendices 1. Proverbs and Sayings on Circassian Customs and Traditions 115 2. Proverbs and Sayings Associated with Hospitality Traditions 141 References and Bibliography 162 4 Introduction IRCASSIAN customs and social norms are enshrined in an orally- C transmitted code called ‘Adige Xabze’—‘Circassian Etiquette’ [«адыгэ хабзэ»]. This rigid and complex system of morals had evolved to ensure that strict militaristic discipline was maintained at all times to defend the country against the many invaders who coveted Circassian lands. In addition, social niceties and graces greased the wheels of social interaction, and a person’s good conduct ensured his survival and prosperity. The Xabze served as the law for ad hoc courts and councils set up to resolve contentious cases and other moot issues, and pronounce binding judgements. -

Dialogues Between a Violin and a Body

Kurs: AA1022 Examensarbete master, folkmusik 30 hp 2021 Konstnärlig masterexamen i musik Institutionen för folkmusik Handlare: Olof Misgeld Coline Genet Dialogues between a violin and a body How to be a dancing musician on stage ? Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt arbete Inspelning av det självständiga, konstnärliga arbetet finns dokumenterat i det tryckta exemplaret av denna text på KMH:s bibliotek . Contents Abstract . .3 PREFACE . .4 1 Introduction . .5 2 Background and concepts . .6 2.1 Performances . .6 2.2 Master and doctoral thesis in artistic research . .7 2.3 Other inspiring artists . .7 2.4 Scientific works . .8 2.5 Concepts . .9 3 Chapter 1: Discovery, dialogue . 14 3.1 Material - The French bourrée ..................... 14 3.2 Construction of the performance . 15 3.3 Space and creativity . 16 4 Chapter 2: Freedom, improvisation . 17 4.1 Upstream work for dance improvisation . 17 4.2 Construction of the performance . 19 4.3 Borders of folk dance and music . 20 5 Chapter 3: Technique, precision, understanding . 21 5.1 Dance meter vs. musical meter . 21 5.1.1 Method . 21 5.1.2 Waltz styles . 22 5.1.3 Polyrhythmic layers: The case of the bourrée . 24 5.2 Dancing and playing at the same time . 26 5.2.1 Common posture . 27 5.2.2 Tune the different meters up . 28 5.2.3 Exercises . 29 5.3 Results . 30 Conclusion . 31 Bibliography 32 References . 33 Appendices . 34 1 The Dancing Musicians - John. B. Vallely 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank Olof Misgeld and Ellika Frisell for supervising this project, inspiring and supporting -

Special Editions; Institute for Balkan Studies SASA

http://www.balkaninstitut.com Serbian A cademy of Sciences and • Department of History, University of Arts, I nstitute for Balkan Studies, California, Santa Barbara Belgrade ( special editions No 39) Prosveta, Export-Import Agency, Belgrade Editors i n chief: • N ikola Tasid, corresponding member, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts • D uSica StoSid, director Prosveta, Export-Import Agency Editorial b oard: • R adovan Samard2id, full member, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts • D imitrije Dordevic, full member Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts • I van Ninid publishing manager Prosveta, Export-Import Agency Secretary: • D r. Milan St. Protid, fellow Serbian A cademy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies The p ublication was financially supported by the "Republidka Zajednica nauke Srbije" http://www.balkaninstitut.com MIGRATIONS I N BALKAN HISTORY BELGRADE 1 989 http://www.balkaninstitut.com £33/ И*1 CIP - К аталогизација у публикацији Народна библиотека Србије, Београд 325.1 ( 497) (082) MIGRATIONS i n Balkan History / [urednik Ivan Ninic]. - Beograd: Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, 1989. - 171 стр. : 24 cm ПК:. a Миграције - Балканско полуострво - Зборници ISBN 8 6-7179-006-1 http://www.balkaninstitut.com ■1130 M l CONTENTS Radovan S amardzic Dimitrije D jordjevid PREFACE 7 Mark. R Stefanovich ETHNICITYND A MIGRATION IN PREHISTORY 9 Nikola T asic PREHISTORIC M IGRATION MOVEMENTS HEIN T BALKANS 29 Robert F rakes THE I MPACT OF THE HUNS IN THE BALKANS I N LATE ANTIQUE HISTORIOGRAPHY 3 9 Henrik B irnbaum WAS T HERE A SLAVIC LANDTAKING OF T HE BALKANS AND, IF SO, ALONG WHAT R OUTES DID IT PROCEED? 47 Dragoljub D ragojlovid MIGRATIONS O F THE SERBS IN THE MIDDLE A GES 61 BariSa K rekic DUBROVNIK A S A POLE OF ATTRACTION AND A P OINT OF TRANSITION FORHE T HINTERLAND POPULATION INHE T LATE MIDDLE AGES 67 Dragan. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Analysis of the Crossover

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Analysis of the Crossover Between Ballroom and Ballet in Choreographic Works THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER FINE ARTS in Dance by Chanel Kostich Thesis Committee: Professor Alan Terricciano, Chair Associate Professor Tong Wang Assistant Professor Vitor Luiz 2020 © 2020 Chanel Kostich TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Dance Autobiography 3 CHAPTER 2: Synopsis & Timeline of the Three Works 7 NYC Ballet: “Vienna Waltzes” 7 Grupo Corpo: “Grande Waltz” 11 Tango Pasión: “Argentine Tango Duet” 16 CHAPTER 3: Contextualizing the Interview with Rodrigo Pedernerias 20 CHAPTER 4: Heat of the Night: A Choreographic Thesis Film 22 Reflection of Thesis Project 30 Appendix 1: MethodoLogy Movement 32 American Smooth Tango Argentine Tango Ballet in Tango Pasión Bolero, Ballet, and Argentine Tango Viennese Waltz Appendix 2: Interview with Rodrigo Pederneiras 39 Appendix 3: Collaborative Design, Copyright Information, Contents of the Music 50 Works Cited 54 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to start by expressing immense gratitude for my thesis chair, Alan Terricciano. Thank you for your encouragement to experiment and be creative within this research process and for your continued patience as we worked through those choices together. Our discussions were always meaningful and impactful to this work, as weLL as to me as a graduate student. I appreciate your kindness, advice, and enthusiasm towards my creative work as we coLLaborated throughout this research process. I would like to thank my thesis committee members Professor Tong Wang and Professor Vitor Luiz for your encouragement and guidance. -

Performance Tango Or Tango Milonguero ?

Performance Tango or Tango Milonguero ? Collected notes : Susana Miller: Two styles of Argentine tango, performance and milonguero, bring about a controversy in the dance community. Some attribute a false dichotomy between these styles. False because, in reality, they are complimentary. In a certain aspect, performance tango and milonguero tango are two sides of the same coin. The Milonguero, or "close embrace" style is danced in the crowded clubs of Buenos Aires. It evolved to compensate for large numbers of couples dancing in limited space. The Milonguero style is a rich and complex form of body signals and incorporates deep respect for the music and its varied rhythms. The result is a form of Tango that allows for simplicity of steps while encouraging a natural connection between the dancers. However, tango is known throughout the world because of performance tango. The beauty and splendor of its figures are spread by TV and on the stages of theaters across great distances to far away places. In this tango the couple separates in order to execute complicated figures and steps that have more visual appeal. They separate because it would be difficult to see the "closed" tango in a large theater of 500 or more people. The body work, particularly the leg motions, would not engender great interest. In the performance tango the steps are based on milonguero style, but are enlarged and embellished, and become choreographies that cross the stage diagonally, creating displays and making full use of the ample space available. The tango is known throughout the world thanks to the artists, very fine and expert dancers, and thanks to their inspiration and the hours of daily work that they devoted to their talent.