Dance-Sector-Review-Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Culture Strategy for Scotland: Analysis of Responses to the Public

A Culture Strategy for Scotland Analysis of responses to the public consultation: Full Analysis Report January 2019 Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Background to the consultation ................................................................................. 1 Profile of respondents ................................................................................................ 1 Analysis and reporting ............................................................................................... 2 A vision for culture in Scotland ............................................................................. 4 Views of those who supported the vision .................................................................. 5 Views of those who did not support the vision .......................................................... 9 Ambition 1: Transforming through culture ......................................................... 10 Views of those who supported the ambition ............................................................ 11 Views of those who did not support the ambition .................................................... 17 Ambition 2: Empowering through culture ........................................................... 25 Views of those who supported the ambition ............................................................ 26 Views of those who did not support the ambition .................................................... 29 -

Image: Brian Hartley

IMAGINATE FESTIVAL Scotland’s international festival of performing arts for children and young people 6-13 may 2013 TICKETS:0131 228 1404 WWW.TRAVERSE.CO.UK Image: Brian Hartley IMAGINATE FESTIVAL FUNDERS & SUPPORT ABOUT IMAGINATE Every year Imaginate receives financial and in kind support from a range of national and international organisations.We would like to thank them all for their invaluable support of the Imaginate Festival. Imaginate is a unique organisation in Scotland,leading in the promotion,development If you would like to know more about our supporters or how to support us,please visit: and celebration of the performing arts for children and young people. www.imaginate.org.uk/support/ We achieve this through the delivery of an integrated M A J O R F U N D E R S BEYONDTHE FESTIVAL annual programme of art-form development, learning supported through the partnerships and performance, including the world Imaginate believes that a high quality creative Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund famous Imaginate Festival, Scotland’s international development programme is the key to unlocking festival of performing arts for children and young people. creativity and supporting artistic excellence in the performing arts sector for children and young people in THE IMAGINATE FESTIVAL Scotland. This programme creates regular opportunities for artists and practitioners, whether they are students, T R U S T S A N D F O U N D AT I O N S PA R T N E R S Every year the Festival and Festival On Tour attracts established artists or at the beginning of their career. -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

The Scottish Banner

thethethe ScottishScottishScottish Banner BannerBanner 44 Years Strong - 1976-2020 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 44 36 Number36 Number Number 6 11 The 11 The world’sThe world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper December May May 2013 2013 2020 Celebrating US Barcodes Hebridean history 7 25286 844598 0 1 The long lost knitting tradition » Pg 13 7 25286 844598 0 9 US Barcodes 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 0 1 7 25286 844598 1 1 The 7 25286 844598 0 9 Stone of 7 25286 844598 1 2 Destiny An infamous Christmas 7 25286 844598 0 3 repatriation » Pg 12 7 25286 844598 1 1 Sir Walter’s Remembering Sir Sean Connery ............................... » Pg 3 Remembering Paisley’s Dryburgh ‘Black Hogmanay’ ...................... » Pg 5 What was Christmas like » Pg 17 7 25286 844598 1 2 for Mary Queen of Scots?..... » Pg 23 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 44 - Number 6 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Contact: Scottish Banner Pty Ltd. The Scottish Banner Editor PO Box 6202 For Auld Lang Syne Sean Cairney Marrickville South, NSW, 2204 forced to cancel their trips. I too was 1929 in Paisley. Sadly, a smoking EDITORIAL STAFF Tel:(02) 9559-6348 meant to be over this year and know film canister caused a panic during Jim Stoddart [email protected] so many had planned to visit family, a packed matinee screening of a The National Piping Centre friends, attend events and simply children’s film where more than David McVey take in the country we all love so 600 kids were present. -

Creative Scotland and the Creative Industries

Creative Industries A Strategy for Creative Scotland 2016-17 Appendix 4 CREATIVE SCOTLAND AND THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES This appendix outlines some of the ways in which Creative Scotland has provided support for some sectors of the creative industries over the past few years. © 2016 Creative Scotland No part of this publication may be reproduced in any format without prior written permission of Creative Scotland. Equal opportunities Creative Scotland operates an equal opportunities policy. Our offices have disabled access. Certain publications can be made available in Gaelic, Scots, in large print, Braille or audio format. Contact Enquiries on 0845 603 6000 Typetalk please prefix number with 18001 For BSL users, use www.contactscotland-bsl.org This document is produced in electronic form by Creative Scotland – please consider the environment and do not print unless you really need to. Please note that we use hyperlinks throughout this document (to link to other publications, research or plans) which won’t be accessible if the document is printed. Your feedback is important to us. Let us know what you think of this publication by emailing [email protected] CREATIVE INDUSTRIES STRATEGY APPENDIX 4 3 Scotland has developed particular expertise in sector development support for the creative industries with well-established organisations that benefit from a closely integrated community of small businesses, creative organisations and individuals. In terms of networks, WASPS provides a large network of 17 studio complexes across Scotland that house a wide range of creative businesses – over 800 tenants. In addition, the Cultural Enterprise Office provides business development support for creative practitioners and micro-businesses, while Arts and Business Scotland acts as a conduit between the cultural and business sectors, helping to nurture creative, social and commercial relationships. -

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Review of the Scottish Animation Sector

__ Review of the Scottish Animation Sector Creative Scotland BOP Consulting March 2017 Page 1 of 45 Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 4 2. The Animation Sector ........................................................................ 6 3. Making Animation ............................................................................ 11 4. Learning Animation .......................................................................... 21 5. Watching Animation ......................................................................... 25 6. Case Study: Vancouver ................................................................... 27 7. Case Study: Denmark ...................................................................... 29 8. Case Study: Northern Ireland ......................................................... 32 9. Future Vision & Next Steps ............................................................. 35 10. Appendices ....................................................................................... 39 Page 2 of 45 This Report was commissioned by Creative Scotland, and produced by: Barbara McKissack and Bronwyn McLean, BOP Consulting (www.bop.co.uk) Cover image from Nothing to Declare courtesy of the Scottish Film Talent Network (SFTN), Studio Temba, Once Were Farmers and Interference Pattern © Hopscotch Films, CMI, Digicult & Creative Scotland. If you would like to know more about this report, please contact: Bronwyn McLean Email: [email protected] Tel: 0131 344 -

Creative Scotland Annual Plan 2014-15

Creative Scotland Annual Plan 2014-15 © 2014 Creative Scotland No part of this publication may be reproduced in any format without prior written permission of Creative Scotland. Equal opportunities Creative Scotland operates an equal opportunities policy. Our offices have disabled access. Certain publications can be made available in Gaelic, in large print, Braille or audio format. Contact Enquiries on 0845 603 6000 Typetalk please prefix number with 18001 This plan is produced in electronic form by Creative Scotland – please consider the environment and do not print unless you really need to Your feedback is important to us. Let us know what you think of this publication by emailing [email protected] Cover: Artists Will Barras and Amy Winstanley painting a Rural Mural at Stranraer Harbour, part of Spring Fling. Photo: Colin Hattersley Contents 5 Introduction 13 Funding, Advocacy, Development and Influencing 15 Our Priorities Over the Next 3 Years 16 Our Priorities Over the Next 12 Months 20 Being a Learning Organisation 24 Our Current Policies 29 Summary Budget 2014-15 37 Planning and Performance 38 Performing Against Our Ambitions 2014-15 52 Delivering National Outcomes 1 Artist Alison Watt and Master Weaver Naomi Robertson, Butterfly tapestry, cutting off ceremony. Photo: courtesy of Dovecot Studios 2 3 Honeyblood at The Great Escape. Photo: Euan Robertson 4 Introduction A Shared Vision We want a Scotland where everyone actively values and celebrates arts and creativity as the heartbeat for our lives and the world in which we live; which continually extends its creative imagination and ways of doing things; and where the arts, screen and creative industries are confident, connected and thriving. -

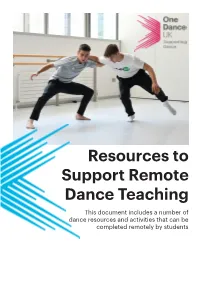

Resources to Support Remote Dance Teaching

Resources to Support Remote Dance Teaching This document includes a number of dance resources and activities that can be completed remotely by students GENERAL RESOURCES: TWINKL resources Twinkl are offering one month ‘ultimate membership’ totally free of charge. To register, visit https://www.twinkl.co.uk/offer and type in the code - UKTWINKLHELPS. The website includes excellent dance resources created by Justine Reeve AKA ‘The Dance Teacher’s Agony Aunt’. ArtsPool ArtsPool are also offering access to their e-learning portal free of charge for 1 month. This is for GCSE groups only. To gain access, email [email protected] BBC A series of street dance videos that could assist learning techniques at home, or support a research project. There are lots of other resources on BBC Teach and School Radio that could assist home study. Click here for more Resource lists for dancers Created by dance education expert Fiona Smith, this document is free to access on the One Dance UK website. It includes links to a variety of YouTube performances that could help students research different styles, cultures and companies. It also includes links to performances that may have been used for GCSE/BTEC/RSL/A LEVEL study. Click here for more BalletBoyz Access to a range of resources that could be used to accompany home study Click here for more 11 Plus A strength and conditioning programme developed at Elmhurst Ballet School and in collaboration with the University of Wolverhampton Click here for more Quizlet Create your own revision cards Click here for more Discover! Creative Careers Research into careers linked to the creative industries Click here for more Create & Dance The Royal Opera House’s creative learning programme with digital activities Click here for more Marquee TV A subscription-based service for viewing dance and other art forms Click here for more Yoga4Dancers Yoga sequences that can be done at home Click here for more 64 Million Artists Will be sharing two weeks of fun, free and accessible creative challeng-es to do at home starting 23rd March. -

Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance

CLR-Nº 6 17/6/08 15:15 Página 85 CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 ˙ VOL VI \ 2008, pp. 85-99 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance PAULINE BROOKS LIVERPOOL JOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT: This article discusses the dance performance project Interface 2, which involved live dancers, animated computer projections (remediated creations of the live section), and the interface of live dancers with dancers on film. It analyses the responses and perceptions of an audience to the changing transformations of the media and the staging of the dance performance. Alongside these responses, I compare and contrast some of the philosophical and aesthetic debates from the past three decades regarding dance and technology in performance, including that of the tension between the acceptance or rejection of «unnatural» remediated bodies and «natural» live bodies moving in the stage space. Keywords: Dance, Remediation, Live, Film, Computer animated. RESUMEN: Este artículo aborda el proyecto de danza Interface 2, que agrupaba bailarines en directo, proyecciones animadas por ordenador (creaciones transducidas de la sección en vivo) y la interfaz de bailarines en vivo con bailarines filmados. Se analizan la respuesta y percepciones del público hacia las transformaciones continuas de los medios tecnológicos de la puesta en escena de la danza. Igualmente, se comparan y contrastan algunos de los debates filosóficos y estéticos de las últimas tres décadas en relación con la danza y el uso de la tecnología en la representación, en particular el referente a la tensión entre la aceptación o rechazo de la falta de «naturalidad» de los cuerpos transducidos y la «naturalidad» de los cuerpos en vivo moviéndose por el espacio escénico. -

A Level Dance Transitions Materials

Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School Year 12 A Level Dance Transition Work To prepare yourself for the A Level Dance course we suggest that you complete some of the following tasks prior to the start of your course. You are not required to complete all tasks. If you don’t understand something, don’t worry, we will revise all of this material briefly at the start of the course. If you have not studied GCSE Dance you should refer to the GCSE Dance revision guide to ensure you are secure in key terminology. Component 1: Solo Practitioner Performance Task Research a few of the following practitioners and find out the key features of their work: Prescribed set works: - Christopher Bruce - Martha Graham - Gene Kelly - Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui Named practitioners: - Glen Tetley - Robert North - Richard Alston - Siobhan Davies - Ashley Page - Filippo Taglioni - August Bournonville - Arthur Saint-Leon - Agnes de Mille - Jack Cole - Jerome Robbins - Bob Fosse - Loie Fuller - Isadora Duncan - Ruth St. Denis - Doris Humphrey - Shobana Jeyasingh - Matthew Bourne - Jasmin Vardimon - Akram Khan - Hofesh Shechter Consider whether any of these practitioners would suit your own strengths and weaknesses in terms of performance. Component 1: Choreography Task Watch examples of dance works from some of the following companies and choreographers to broaden your knowledge of different styles of dance: ● Matthew Bourne’s New Adventures ● Ballet Boyz ● Rambert Dance Company ● Boy Blue Entertainment ● Akram Khan Dance Company ● Shobana Jeyasingh Dance ● Motionhouse Dance Company ● StopGap Dance Company ● DV8 Physical Theatre ● Phoenix Dance Theatre ● James Cousins Company ● The Royal Ballet (Wayne McGregor) ● Jasmin Vardimon ● Hofesh Schecter Note how they manipulate dancers and movement material and recognise key choreographic devices that the choreographers have used. -

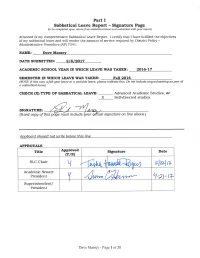

MASSEY Dave Slreport S17

Parts II-V Sabbatical Leave Report II. Re-statement of Sabbatical Leave Application The intention behind this sabbatical proposal is to study contemporary dance forms from internationally and nationally recognized artists in Israel, Europe, and the U.S. The plan is to take daily dance class, week long workshops, to observe dance class and company rehearsals, and interview directors, choreographers, and artists to gain further insight into their movement creation process. This study will benefit my teaching, choreographic awareness, and movement research, which will benefit my students and my department as courses are enhanced by new methodologies, techniques and strategies. The second part of this plan is to visit California colleges and universities to investigate how contemporary dance is being built into their curriculum. Creating a dialogue with my colleagues about this developing dance genre will be important as my department implements contemporary dance into its curriculum. The third part of the sabbatical is to co-produce a dance concert in the San Diego area showcasing choreography that has been created using some of the new methodologies, techniques and strategies founded and discussed while on sabbatical. I will document all hours in a spreadsheet submitted with my sabbatical report. I estimate 580 hours. III. Completion of Objectives, Description of Activities Objective #1: a. To explore, learn, and document best practices in Contemporary Dance b. I started my sabbatical researching contemporary dance and movement. I scoured the web for journals, magazines, videos that gave me insight into how people in dance were talking about this contemporary genre. I also read several books that were thought-provoking about contemporary movement, training and the contemporary dancer.