Mattingly Final(Numbered)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

PRESS CONTACT National Press

HONORARY CHAIRPERSONS Mrs. Laura Bush Mrs. Hillary Rodham Clinton Mrs. George Bush (1925-2018) Mrs. Nancy Reagan (1921-2016) Mrs. Rosalynn Carter Mrs. Be y Ford (1918–2011) BOARD OF DIRECTORS Curt C. Myers, Chairman Jodee Nimerichter, President PRESS CONTACT Russell Savre, Treasurer Nancy Carver McKaig, Secretary National Press Representative: Lisa Labrado Charles L. Reinhart, Director Emeritus [email protected] Bernard E. Bell Susan M. Carson Direct: 646-214-5812/Mobile: 917-399-5120 Nancy P. Carstens Natalie W. Dunn Rebecca B. Elvin North Carolina Press Representative: Sarah Tondu Richard E. Feldman, Esq. [email protected] James Frazier, Ed.D. omas R. Galloway Office: 919-684-6402/Mobile: 919-270-9100 Susan T. Hall, Ph.D. Carlton Midye e Adam Reinhart, Ph.D. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Arthur H. Rogers III Judith Sagan THE AMERICAN DANCE FESTIVAL’S 85TH SEASON CONTINUES INTO WEEK #2 Week #2 Features the Return of Paul Taylor Dance Company and Ronald K. Brown/EVIDENCE, the Debut of Anne Plamondon, the Presentation of the 2018 Samuel H. Scripps/ADF Award to Ronald K. Brown, and a Special Children’s Matinee Performance Durham, NC, June 12, 2018—The American Dance Festival (ADF) kicks off week #2 with stunning, ADVISORY COMMITTEE classic works by Paul Taylor Dance Company on June 26 and June 27 at Durham Performing Arts Robby Barne Center. Ronald K. Brown/EVIDENCE returns with an evening of soul stirring dances June 28-30 at Brenda Brodie Ronald K. Brown Reynolds Industries Theater. Ronald K. Brown will receive the Samuel H. Scripps/ADF Award prior Martha Clarke to the performance on June 28. -

Welcome Letter 2013 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival

Welcome Letter 2013 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award Lin Hwai-min The ADF wishes to thank the late Samuel H. Scripps, whose generosity made possible the annual $50,000 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award. The Award was established in 1981 as the first of its kind and honors chorographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of modern dance. The continuation of the award is made possible through the SHS Foundation and its President, Richard E. Feldman. Celebrated choreographer, director, and educator Lin Hwai-min will be presented with the 2013 Award by Joseph V. Melillo in a special ceremony on Saturday, July 27th at 8:00 pm, prior to the Forces of Dance performance at the Durham Performing Arts Center. The program will also include a performance of the solo from Lin Hwai-min’s 1998 work Moon Water, performed by Cloud Gate Dance Theatre dancer Chou Chang-ning. Mr. Lin’s fearless zeal for the art form has established him as one of the most dynamic and innovative choreographers today. His illustrious career as a choreographer has spanned over four decades and has earned him international praise for his impact on Chinese modern dance. He is the founder, choreographer, and artistic director of both Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan (founded in 1973) and Cloud Gate 2 (founded in 1992), and his choreography continues to be presented throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia. While his works often draw inspiration from traditional elements of Asian culture and aesthetics, his choreographic brilliance continues to push boundaries and redefine the art form. -

Paul Taylor Dance Company’S Engagement at Jacob’S Pillow Is Supported, in Part, by a Leadership Contribution from Carole and Dan Burack

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Suzanne Carbonneau TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through It is said that the body doesn’t lie, but this is wishful thinking. All earthly creatures do it, only some more artfully than others. annual gifts of $10,000 and above. —Paul Taylor, Private Domain Their deep affiliation ensures the success and longevity of the It was Martha Graham, materfamilias of American modern dance, who coined that aphorism about the inevitability of truth Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public emerging from movement. Considered oracular since its first utterance, over time the idea has only gained in currency as one of programs, The School, the Archives, and more. those things that must be accurate because it sounds so true. But in gently, decisively pronouncing Graham’s idea hokum, choreographer Paul Taylor drew on first-hand experience— $25,000+ observations about the world he had been making since early childhood. To wit: Everyone lies. And, characteristically, in his 1987 autobiography Private Domain, Taylor took delight in the whole business: “I eventually appreciated the artistry of a movement Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister PRESENTS lie,” he wrote, “the guilty tail wagging, the overly steady gaze, the phony humility of drooping shoulders and caved-in chest, the PAUL TAYLOR The Barrington Foundation Wendy McCain decorative-looking little shuffles of pretended pain, the heavy, monumental dances of mock happiness.” Frank & Monique Cordasco Fred Moses* DANCE COMPANY Hon. -

September 2014

September 2014 America The Beautiful! different hospitality experience. We gladly copied their model 2014 NATIONAL SMOOTH of starting the weekend with a full-fledged dinner that not DANCERS CONVENTION only allowed more people to enjoy a welcoming experience but Hosted by The Palomar Chapter which also added nearly 3 hours of dancing to our opening A MESSAGE FROM PETER & MARSHA HANSEN evening. -Thanks also to Mike Cowlishaw of the San Diego Chapter A lot of thank you’s are in order for the success of 2014 and Dennis Acosta of the Bakersfield Chapter for agreeing to NSD Convention that was held in Palm Springs over Labor provide the music for 2 of our sessions. Their smooth expertise Day weekend, but with your indulgence, we would like to was very welcome. start with a huge thank you to the members of the Palomar -Thanks to the Southern California chapters (San Diego, Chapter. We think it was evident to all in attendance that the San Fernando Valley and Los Angeles) for hosting our post Chapter put together a terrific team effort in all aspects. We dance hospitalities. had a lot of learning on the job, as it had been 14 years since -We enjoyed watching the competitors and formation teams the Palomar Chapter had hosted a Convention; most of our who entertained us throughout the weekend and we appreciate current members were not even members at that time. We the time and effort they spent in preparation for these events. couldn’t be prouder of the job that our members did and hope -Many dancers also participated in the Jack & Jill contests you all will join us in applauding a job well done. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance

CLR-Nº 6 17/6/08 15:15 Página 85 CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 ˙ VOL VI \ 2008, pp. 85-99 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance PAULINE BROOKS LIVERPOOL JOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT: This article discusses the dance performance project Interface 2, which involved live dancers, animated computer projections (remediated creations of the live section), and the interface of live dancers with dancers on film. It analyses the responses and perceptions of an audience to the changing transformations of the media and the staging of the dance performance. Alongside these responses, I compare and contrast some of the philosophical and aesthetic debates from the past three decades regarding dance and technology in performance, including that of the tension between the acceptance or rejection of «unnatural» remediated bodies and «natural» live bodies moving in the stage space. Keywords: Dance, Remediation, Live, Film, Computer animated. RESUMEN: Este artículo aborda el proyecto de danza Interface 2, que agrupaba bailarines en directo, proyecciones animadas por ordenador (creaciones transducidas de la sección en vivo) y la interfaz de bailarines en vivo con bailarines filmados. Se analizan la respuesta y percepciones del público hacia las transformaciones continuas de los medios tecnológicos de la puesta en escena de la danza. Igualmente, se comparan y contrastan algunos de los debates filosóficos y estéticos de las últimas tres décadas en relación con la danza y el uso de la tecnología en la representación, en particular el referente a la tensión entre la aceptación o rechazo de la falta de «naturalidad» de los cuerpos transducidos y la «naturalidad» de los cuerpos en vivo moviéndose por el espacio escénico. -

Dance Motion

ww 2013 Next Wave Festival 2013 Next Wave Festival Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, SM ABOUT DANCEMOTION USA to connect with us online. Chairman of the Board DANCEMOTIONUSA.ORG William I. Campbell, SM DanceMotion USA is a program of the Vice Chairman of the Board Bureau of Educational and Cultural Announcing our Season 4 tours: Adam E. Max, Affairs of the US Department of State, DanceMotion Vice Chairman of the Board produced by BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Mark Morris Dance Group Karen Brooks Hopkins, Music), to showcase the finest contem- (Burma, Cambodia, and Timor-L’este) President porary American dance abroad while David Dorfman Dance SM facilitating cultural exchange and mutual (Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) Joseph V. Melillo, USA Executive Producer understanding. DanceMotion USASM CONTRA-TIEMPO helps US embassies partner with leading (Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia) DOUG VARONE AND DANCERS cultural, social service, and community- BRENDA ANGIEL AERIAL based organizations and educational Beginning March 2014 institutions to create unique residencies DANCE COMPANY that allow for exchange and engage- ment. In addition to person-to-person DATES: Oct 10—12 at 7:30pm interactions, the program reaches a Oct 13 at 3:00pm wider audience through an active social and digital media initiative, and through LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) educational resources housed in em- bassy and consulate libraries. RUN TIME: 1hr 40 min with 2 intermissions Since the launch of DanceMotion USASM ARTIST TALK: Doug Varone and Brenda Angiel in 2010, 14 American dance companies Moderated by Deborah Jowitt have toured to different regions around Fri, Oct 11 post-show the globe, including Sub-Saharan and BAM Fishman Space A program of: Northern Africa, South America, the Free for same-day ticket holders Middle East, the Iberian Peninsula, and Central, South and Southeast Asia. -

MASSEY Dave Slreport S17

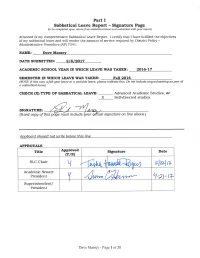

Parts II-V Sabbatical Leave Report II. Re-statement of Sabbatical Leave Application The intention behind this sabbatical proposal is to study contemporary dance forms from internationally and nationally recognized artists in Israel, Europe, and the U.S. The plan is to take daily dance class, week long workshops, to observe dance class and company rehearsals, and interview directors, choreographers, and artists to gain further insight into their movement creation process. This study will benefit my teaching, choreographic awareness, and movement research, which will benefit my students and my department as courses are enhanced by new methodologies, techniques and strategies. The second part of this plan is to visit California colleges and universities to investigate how contemporary dance is being built into their curriculum. Creating a dialogue with my colleagues about this developing dance genre will be important as my department implements contemporary dance into its curriculum. The third part of the sabbatical is to co-produce a dance concert in the San Diego area showcasing choreography that has been created using some of the new methodologies, techniques and strategies founded and discussed while on sabbatical. I will document all hours in a spreadsheet submitted with my sabbatical report. I estimate 580 hours. III. Completion of Objectives, Description of Activities Objective #1: a. To explore, learn, and document best practices in Contemporary Dance b. I started my sabbatical researching contemporary dance and movement. I scoured the web for journals, magazines, videos that gave me insight into how people in dance were talking about this contemporary genre. I also read several books that were thought-provoking about contemporary movement, training and the contemporary dancer. -

American Realness 2016 January 7-17, 2016

CONTACT: BEN PRYOR, [email protected] tbspMGMT and Abrons Arts Center Present AMERICAN REALNESS 2016 JANUARY 7-17, 2016 ABRONS ARTS CENTER, 466 GRAND STREET AT PITT STREET F, J, M, Z TRAINS TO DELANCEY/ESSEX, B, D TRAINS TO GRAND ST American Realness returns January 7-17, 2016, for its seventh consecutive season at Abrons Arts Center. The festival utilizes all three theater and gallery spaces at Abrons and includes off-site engagements presented by Sunday Sessions at MoMA PS1, and Gibney Dance Center to construct a composition of dance, theater, music theater, performance and hybrid performative works featuring four world premieres, six U.S. premieres, three New York premieres, six engagements and one special-event work in progress presentation for a total of sixty-seven performances of nineteen productions over eleven days. Featuring artists from across the U.S. with a concentration of New York makers and a small selection of international artists, American Realness offers audiences local, national, and international perspectives on the complicated and wondrous world we inhabit. Through visceral, visual, and text-based explorations of perception, sensation, form and attention, artists expose issues and questions around identity, ritual, blackness, history, pop-culture, futurity, and consumption in an American-focused, globally-minded context. American Realness 2016 presents: Four World Premieres: Erin Markey, A Ride on the Irish Cream Jillian Peña, Panopticon co-presented with Performance Space 122 The Bureau for the Future of Choreography, -

Artist Bios and Piece Descriptions

1 PERFORMANCE MIX ARTISTS 2013:BIOGRAPHIES Renée Archibald presents Shake Shake, a duet that brings new life to the old cliché of the dancer’s body as instrument. The work investigates sound as a kinetic sense, with rhythm accumulating and dissolving into sempiternal metabolic process and tumbling into finely-tuned cacophony that animates the performance space with lush visual noise. Shake Shake is performed by Jennifer Lafferty and Renée Archibald. Archibald is currently a third year MFA candidate and Teaching Assistant in The Department of Dance at the University of Illinois. After receiving a BFA from University of North Carolina School of the Arts, Archibald lived in New York City for ten years where she performed with independent artists including Christopher Williams, Ann Liv Young, and Rebecca Lazier. Her choreographic work has been presented at NY venues including The Brooklyn Museum, The Chocolate Factory, Danspace Project, Dance Theater Workshop, and The Kitchen. Archibald has taught at Barnard College and White Mountain Summer Dance Festival and has received choreographic residencies through the Brooklyn Arts Exchange, Movement Research, and Yaddo. In 2012, she was awarded the U of Dance Department's Vannie L. Sheiry Memorial Scholarship for outstanding performance. vimeo.com/reneearchibald Oren Barnoy presents Angels My House I Promise. Barnoy dives into an unknown world of dance while investigating not knowing. This experience of dancing is somewhere between ritual, improvisation, score, therapy, and set choreography. It produces itself. Barnoy showed his choreography between 2000-2004 at Joyce SoHo, PS1, Dancenow, Galapagos, WAX. In 2005, Barnoy took a four year break from dance and moved to Miami.