Passion, Pathways and Potential in Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Dance and Health: a Review of the Literature

Feature Article Cultural Dance and Health: A Review of the Literature Anna E. Olvera ABSTRACT Physical activity has many physical and mental health outcomes. However, physical inactivity continues to be com- mon. Dance, specifically cultural dance, is a type of physical activity that may appeal to some who are not otherwise active and may be a form of activity that is more acceptable than others in certain cultures. The purpose of this paper is to summarize literature describing the health benefits of cultural dance. Several databases were searched to identify articles published within the last 15 years, describing physical and mental health outcomes of cultural dance or inter- ventions that incorporated cultural dance. In the seven articles reviewed there is evidence to support the use of cultural dance for preventing excessive weight gain and cardiac risk, reducing stress, and increasing life satisfaction. Cultural dance is a practical form of physical activity to promote physical and mental health among subgroups of populations that often have lower amounts of participation in physical activity. There is a need for additional research to isolate how and in what ways cultural dance can be offered to promote physical activity. Practitioners should consider non- traditional forms of physical activity, offered in partnership with community organizations. BACKGROUND income. One survey conducted between ditional physical activities and gym classes.7 Physical activity is important to a healthy 1999 and 2002 found significant differ- Women in minority groups, specifically lifestyle. With health problems such as dia- ences in BMI between African-American African-American and Mexican American betes1 and obesity2 reaching epidemic pro- and Caucasian girls (p < 0.001) with rates women, tend to have higher levels of leisure portions, there is a need for programs that of 20.4% and 19.0%, respectively). -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

Changing Perspectives Through Somatically Informed Dance Praxis Reflections of One to One Dance and Parkinson’S Practice As Home Performance

DOCTORAL THESIS Changing perspectives through somatically informed dance praxis reflections of one to one dance and Parkinson’s practice as home performance Brierley, Melanie Award date: 2021 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1 Changing perspectives through somatically informed dance praxis: Reflections of one to one Dance and Parkinson’s practice as ‘Home Performance’. By Melanie Brierley: MA, RSME/T, BA, PGCE. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Dance University of Roehampton 2020 2 The research for this project was submitted for ethics consideration under the reference DAN 13/008 in the Department of Dance and was approved under the procedures of the University of Roehampton Ethics Committee on 22/07/13. 3 Acknowledgements I would especially like to thank my Director of Studies, Professor Emilyn Claid, and my PhD Supervisor Dr Sara Houston for their advice during the research and writing of my thesis. -

Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance

CLR-Nº 6 17/6/08 15:15 Página 85 CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 ˙ VOL VI \ 2008, pp. 85-99 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance PAULINE BROOKS LIVERPOOL JOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT: This article discusses the dance performance project Interface 2, which involved live dancers, animated computer projections (remediated creations of the live section), and the interface of live dancers with dancers on film. It analyses the responses and perceptions of an audience to the changing transformations of the media and the staging of the dance performance. Alongside these responses, I compare and contrast some of the philosophical and aesthetic debates from the past three decades regarding dance and technology in performance, including that of the tension between the acceptance or rejection of «unnatural» remediated bodies and «natural» live bodies moving in the stage space. Keywords: Dance, Remediation, Live, Film, Computer animated. RESUMEN: Este artículo aborda el proyecto de danza Interface 2, que agrupaba bailarines en directo, proyecciones animadas por ordenador (creaciones transducidas de la sección en vivo) y la interfaz de bailarines en vivo con bailarines filmados. Se analizan la respuesta y percepciones del público hacia las transformaciones continuas de los medios tecnológicos de la puesta en escena de la danza. Igualmente, se comparan y contrastan algunos de los debates filosóficos y estéticos de las últimas tres décadas en relación con la danza y el uso de la tecnología en la representación, en particular el referente a la tensión entre la aceptación o rechazo de la falta de «naturalidad» de los cuerpos transducidos y la «naturalidad» de los cuerpos en vivo moviéndose por el espacio escénico. -

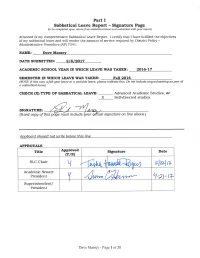

MASSEY Dave Slreport S17

Parts II-V Sabbatical Leave Report II. Re-statement of Sabbatical Leave Application The intention behind this sabbatical proposal is to study contemporary dance forms from internationally and nationally recognized artists in Israel, Europe, and the U.S. The plan is to take daily dance class, week long workshops, to observe dance class and company rehearsals, and interview directors, choreographers, and artists to gain further insight into their movement creation process. This study will benefit my teaching, choreographic awareness, and movement research, which will benefit my students and my department as courses are enhanced by new methodologies, techniques and strategies. The second part of this plan is to visit California colleges and universities to investigate how contemporary dance is being built into their curriculum. Creating a dialogue with my colleagues about this developing dance genre will be important as my department implements contemporary dance into its curriculum. The third part of the sabbatical is to co-produce a dance concert in the San Diego area showcasing choreography that has been created using some of the new methodologies, techniques and strategies founded and discussed while on sabbatical. I will document all hours in a spreadsheet submitted with my sabbatical report. I estimate 580 hours. III. Completion of Objectives, Description of Activities Objective #1: a. To explore, learn, and document best practices in Contemporary Dance b. I started my sabbatical researching contemporary dance and movement. I scoured the web for journals, magazines, videos that gave me insight into how people in dance were talking about this contemporary genre. I also read several books that were thought-provoking about contemporary movement, training and the contemporary dancer. -

Dance Intervention for Adolescent Girls

Dance Intervention for Adolescent Girls Dedication To all adolescent girls Örebro Studies in Medicine 144 ANNA DUBERG Dance Intervention for Adolescent Girls with Internalizing Problems Effects and Experience Cover picture: Claes Lybeck © Anna Duberg, 2016 Title: Dance Intervention for Adolescent Girls with Internalizing Problems Effects and Experiences Publisher: Örebro University 2016 www.oru.se/publikationer-avhandlingar Print: Örebro University, Repro 04/2016 ISSN 1652-4063 ISBN 978-91-7529-140-6 Abstract Anna Duberg (2016) Dance Intervention for Adolescent Girls with Internalizing Problems. Effects and Experiences. Örebro Studies in Medical Science 144. Globally, psychological health problems are currently among the most serious public health challenges. Adolescent girls suffer from internalizing problems, such as somatic symptoms and mental health problems, at higher rates than in decades. By age 15, over 50 % of all girls experience multiple health complaints more than once a week and one in five girls reports fair or poor health. The overall aim of this study was to investigate the effects of and experiences with an after-school dance intervention for adolescent girls with internalizing problems. The intervention comprised dance that focused on resources twice weekly for 8 months. Specifically, this thesis aimed to: I) investigate the effects on self-rated health (SRH), adherence and over-all experience; II) evaluate the effects on somatic symptoms, emotional distress and use of medication; III) explore the experiences of those participating in the intervention; and IV) assess the cost-effectiveness. A total of 112 girls aged 13 to 18 years were included in a randomized con- trolled trial. The dance intervention group comprised 59 girls, and the control group 53. -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Music, Dance and Swans the Influence Music Has on Two Choreographies of the Scene Pas D’Action (Act

Music, Dance and Swans The influence music has on two choreographies of the scene Pas d’action (Act. 2 No. 13-V) from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake Naam: Roselinde Wijnands Studentnummer: 5546036 BA Muziekwetenschap BA Eindwerkstuk, MU3V14004 Studiejaar 2017-2018, block 4 Begeleider: dr. Rebekah Ahrendt Deadline: June 15, 2018 Universiteit Utrecht 1 Abstract The relationship between music and dance has often been analysed, but this is usually done from the perspective of the discipline of either music or dance. Choreomusicology, the study of the relationship between dance and music, emerged as the field that studies works from both point of views. Choreographers usually choreograph the dance after the music is composed. Therefore, the music has taken the natural place of dominance above the choreography and can be said to influence the choreography. This research examines the influence that the music has on two choreographies of Pas d’action (act. 2 no. 13-V), one choreographed by Lev Ivanov, the other choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev from the ballet Swan Lake composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by conducting a choreomusicological analysis. A brief history of the field of choreomusicology is described before conducting the analyses. Central to these analyses are the important music and choreography accents, aligning dance steps alongside with musical analysis. Examples of the similarities and differences between the relationship between music and dance of the two choreographies are given. The influence music has on these choreographies will be discussed. The results are that in both the analyses an influence is seen in the way the choreography is built to the music and often follows the music rhythmically. -

Library of Congress Collection Overviews: Dance

COLLECTION OVERVIEW DANCE I. SCOPE This overview focuses on dance materials found throughout the Library’s general book collection as well as in the various special collections and special format divisions, including General Collections; the Music Division; Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound; the American Folklife Center; Manuscript Division; Prints & Photographs; and Rare Book and Special Collections. The overview also identifies dance- related Internet sources created by the Library as well as subscription databases. II. SIZE Dance materials can be found in the following classes: BJ; GT; VN; GV; M; and ML. All classes, when totaled, add up to 57,430 dance and dance-related items. Class GV1580- 1799.4 (Dancing) contains 10,114 items, constituting the largest class. The Music Division holds thirty special collections of dance materials and an additional two hundred special collections in music and theater that include dance research materials. III. GENERAL RESEARCH STRENGTHS General research strengths in the area of dance research at the Library of Congress fall within three areas: (A) dance instructional and etiquette manuals, especially those printed between 1520 and 1920, (B) dance on camera, and (C) folk, traditional, and ethnic dance. A. The first primary research strength of the Library of Congress is its collections of 16th-20th-century dance instructional and etiquette manuals and ancillary research materials, which are located in the General Collections, Music Division, and Rare Book and Special Collections (sub-classifications GN, GT, GV, BJ, and M). Special Collections within the Music Division that compliment this research are numerous, including its massive collection of sheet music from the early 1800s through the 20th century. -

Exegesis for Phd in Creative Practice SVEBOR SEČAK Shakespeare's Hamlet in Ballet—A Neoclassical and Postmodern Contemporary Approach

Exegesis for PhD in Creative Practice SVEBOR SEČAK Shakespeare's Hamlet in Ballet—A Neoclassical and Postmodern Contemporary Approach INTRODUCTION In this exegesis I present my PhD project which shows the transformation from a recording of a neoclassical ballet performance Hamlet into a post-postmodern artistic dance video Hamlet Revisited. I decided to turn to my own choreography of the ballet Hamlet which premiered at the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb in 2004, in order to revise it with a goal to demonstrate the neoclassical and the contemporary postmodern approach, following the research question: How to transform an archival recording of a neoclassical ballet performance into a new artistic dance video by implementing postmodern philosophical concepts? This project is a result of my own individual transformations from a principal dancer who choreographs the leading role for himself, into a more self-reflective mature artist as a result of aging, the socio-political changes occurring in my working and living environment, and my academic achievements, which have exposed me to the latest philosophical and theoretical approaches. Its significance lies in establishing communication between neoclassical and postmodern approaches, resulting in a contemporary post-postmodern artistic work that elucidates the process in the artist's mind during the creative practice. It complements my artistic and scholarly work and is an extension built on my previous achievements implementing new comprehensions. As a life-long ballet soloist and choreographer my area of interest is the performing arts, primarily ballet and dance and the dualism between the abstract and the narrative approaches 1 Exegesis for PhD in Creative Practice SVEBOR SEČAK Shakespeare's Hamlet in Ballet—A Neoclassical and Postmodern Contemporary Approach to ballet works1. -

The Evolution of Dance As a Storytelling Device in the Integrated Musical

Dance Speaks Where Words fail: the Evolution of Dance as a Storytelling Device in the Integrated Musical. In partial fulfilment of the requirements for Honours in Theatre and Drama Murdoch University by Ellin Sears 30881438 1 This thesis is presented for the Honours degree in Theatre and Drama Studies at Murdoch University, 2012. I, Ellin Sears, declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution. Information quoted or paraphrased from the work of others has been acknowledged in the footnotes and a full bibliography is provided at the end of this work Signed ……………………………… Date………………………………… 2 COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s51.2 of the Copyright Act 1968, all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such a reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: …………………………………………………………... Full Name of Degree: …………………………………………………………………... e.g. Bachelor of Science with Honours in Chemistry. Thesis Title: …………………………………………………………………... …………………………………………………………………... …………………………………………………………………... …………………………………………………………………... Author: …………………………………………………………………... Year: ………………………………………………………………....... 3 Contents: Abstract – p5 Acknowledgements – p6 Introduction and Literature Review – p7 Part One – Musicals and Analysis: An Ongoing Struggle – p10 - Genre Theory - Towards a Theory of Integration - Doubled Time: A New Critical Perspective? Part Two – Dance in the Integrated Musical: A Case Study – p17 Part Three – Commentary on Twelfth Night and Gesamtkunstwerk – p25 Appendices – p58 Bibliography – p77 4 ABSTRACT Musical Theatre has long suffered the stigma of being perceived as a low form of art by scholars and critics alike. -

2019 Gold Medal Ceremony Program Book

The seals on the cover represent the two sides of The Congressional Award Medal. The Capitol Dome is surrounded by 50 stars, representing the states of the Union, and is bordered by the words, “Congressional Award.” Bordering the eagle are the words that best define the qualities found in those who have earned this honor, “Initiative – Service – Achievement” The Congressional Award Public Law 96-114, The Congressional Award Act 2019 Gold Medal Ceremony The Congress of the United States United States Capitol Washington, D.C. It is my honor and privilege to applaud the achievements of the recipients of the 2019 Congressional Award Gold Medal. These outstanding 538 young Americans have challenged themselves and made lasting contributions to local communities across this great nation. This is our largest class of Gold Medalists to date! The Gold Medal Ceremony is the culmination of a long journey for our awardees. For each participant the journey was unique, but one that likely included many highs and lows. The Congressional Award program was designed to instill a wide range of life skills and attributes that are necessary to navigate and overcome obstacles on the path to success - both in the classroom and beyond. And now that each young person has met these challenges and attained their goals, we hope they will continue to amaze and inspire us by pursuing their passions, utilizing their talents, and demonstrating an unwavering commitment to making the world a better place. On behalf of the Board of Directors, we would like to extend our great appreciation to our partner organizations and sponsors for their continued support.