Articulating Dance Improvisation: Knowledge Practices in the College Dance Studio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stagehand Course Curriculum

Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Stagehand Training Effective July 1, 2010 1 Table of Contents Grip 3 Lead Audio 4 Audio 6 Audio Boards Operator 7 Lead Carpenter 9 Carpenter 11 Lead Fly person 13 Fly person 15 Lead Rigger 16 Rigger 18 Lead Electrician 19 Electrician 21 Follow Spot operator 23 Light Console Programmer and Operator 24 Lead Prop Person 26 Prop Person 28 Lead Wardrobe 30 Wardrobe 32 Dresser 34 Wig and Makeup Person 36 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts 2 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Stagecraft Class (Grip) Outline A: Theatrical Terminology 1) Stage Directions 2) Common theatrical descriptions 3) Common theatrical terms B: Safety Course 1) Definition of Safety 2) MSDS sheets description and review 3) Proper lifting techniques C: Instruction of the standard operational methods and chain of responsibility 1) Review the standard operational methods 2) Review chain of responsibility 3) Review the chain of command 4) ACPA storage of equipment D: Basic safe operations of hand and power tools E: Ladder usage 1) How to set up a ladder 2) Ladder safety Stagecraft Class Exam (Grip) Written exam 1) Stage directions 2) Common theatrical terminology 3) Chain of responsibility 4) Chain of command Practical exam 1) Demonstration of proper lifting techniques 2) Demonstration of basic safe operations of hand and power tools 3) Demonstration of proper ladder usage 3 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Lead Audio Technician Class Outline A: ACPA patching system Atwood, Discovery, and Sydney 1) Knowledge of patch system 2) Training on patch bays and input signal routing schemes for each theater 3) Patch system options and risk 4) Signal to Voth 5) Do’s and Don’ts B: ACPA audio equipment knowledge and mastery 1) Audio system power activation 2) Installation and operation of a mixing consoles 3) Operation of the FOH PA system 4) Operation of the backstage audio monitors 5) Operation of Center auxiliary audio systems a. -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

Robert Lepage's Scenographic Dramaturgy: the Aesthetic Signature at Work

1 Robert Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy: The Aesthetic Signature at Work Melissa Poll Abstract Heir to the écriture scénique introduced by theatre’s modern movement, director Robert Lepage’s scenography is his entry point when re-envisioning an extant text. Due to widespread interest in the Québécois auteur’s devised offerings, however, Lepage’s highly visual interpretations of canonical works remain largely neglected in current scholarship. My paper seeks to address this gap, theorizing Lepage’s approach as a three-pronged ‘scenographic dramaturgy’, composed of historical-spatial mapping, metamorphous space and kinetic bodies. By referencing a range of Lepage’s extant text productions and aligning elements of his work to historical and contemporary models of scenography-driven performance, this project will detail how the three components of Lepage’s scenographic dramaturgy ‘write’ meaning-making performance texts. Historical-Spatial Mapping as the foundation for Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy In itself, Lepage’s reliance on evocative scenography is inline with the aesthetics of various theatre-makers. Examples range from Appia and Craig’s early experiments summoning atmosphere through lighting and minimalist sets to Penny Woolcock’s English National Opera production of John Adams’s Dr. Atomic1 which uses digital projections and film clips to revisit the circumstances leading up to Little Boy’s release on Hiroshima in 1945. Other artists known for a signature visual approach to locating narrative include Simon McBurney, who incorporates digital projections to present Moscow via a Google Maps perspective in Complicité’s The Master and Margarita and auteur Benedict Andrews, whose recent production of Three Sisters sees Chekhov’s heroines stranded on a mound of dirt at the play’s conclusion, an apt metaphor for their dreary futures in provincial Russia. -

Rudolf Laban in the 21St Century: a Brazilian Perspective

DOCTORAL THESIS Rudolf Laban in the 21st Century: A Brazilian Perspective Scialom, Melina Award date: 2015 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Rudolf Laban in the 21st Century: A Brazilian Perspective By Melina Scialom BA, MRes Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Dance University of Roehampton 2015 Abstract This thesis is a practitioner’s perspective on the field of movement studies initiated by the European artist-researcher Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) and its particular context in Brazil. Not only does it examine the field of knowledge that Laban proposed alongside his collaborators, but it considers the voices of Laban practitioners in Brazil as evidence of the contemporary practices developed in the field. As a modernist artist and researcher Rudolf Laban initiated a heritage of movement studies focussed on investigating the artistic expression of human beings, which still reverberates in the work of artists and scholars around the world. -

Term-List-For-Ch4-Asian-Theatre-2

Asian Theatre: India, China, Korea, Japan, Indonesia, & Cambodia Cultural Periods and Events Theatrical Developments Persons Aryan migration & caste system Natya-Shastra (rasas & the Bharata Muni & Abhinavagupta Vedic & Gandhara Periods spectator’s liberation) Shūdraka & Kalidasa Hinduism & Sanskrit texts Islamic invasions actor-manager (sudtradhara) Buddhism (promising what?) shamanic rituals jester (vidushaka) Hellenistic influence court entertainments with string-puller (sudtradhara) Classical Period & Ashoka Jester Ming sheng, dan, jing, & chou (meanings) Theravada & Mahayana wrestling & Baixi men & women who played across gender Gupta golden age impersonations, dances, & women who led troupes Medieval Period acrobatics, sword tricks Guan Hanqing Muslim invasions small plays of song and dance Tang Xianzu Chola Dynasty Pear Garden & adjutant Li Yu Early Modern Period plays Kan’ami & Zeami Mughal Empire red light districts with shite & shite-tsure (across gender), waki, Colonial Period with British East southern dramas & waki-tsure, & kyogen India Company variety show musicals chorus of 8 men, musicians, & onstage British Raj with one star singing per stagehand (kuroko) Dramatic Performances Act act Okuni Contemporary Period complex, poetic dramas onnagata Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han, Jin, kun operas with plaintive Chikamatsu Northern & Southern, Sui, Tang, music & flowing Danjuro I Song, Yuan, Ming, & Qing melodies/dancing chanter, 3 puppeteers per puppet, & Dynasties Beijing Opera (jingju) as shamisen player nationalist & communist rulers -

Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance

CLR-Nº 6 17/6/08 15:15 Página 85 CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 ˙ VOL VI \ 2008, pp. 85-99 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Remediation of Moving Bodies: Aesthetic Perceptions of a Live, Digitised and Animated Dance Performance PAULINE BROOKS LIVERPOOL JOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT: This article discusses the dance performance project Interface 2, which involved live dancers, animated computer projections (remediated creations of the live section), and the interface of live dancers with dancers on film. It analyses the responses and perceptions of an audience to the changing transformations of the media and the staging of the dance performance. Alongside these responses, I compare and contrast some of the philosophical and aesthetic debates from the past three decades regarding dance and technology in performance, including that of the tension between the acceptance or rejection of «unnatural» remediated bodies and «natural» live bodies moving in the stage space. Keywords: Dance, Remediation, Live, Film, Computer animated. RESUMEN: Este artículo aborda el proyecto de danza Interface 2, que agrupaba bailarines en directo, proyecciones animadas por ordenador (creaciones transducidas de la sección en vivo) y la interfaz de bailarines en vivo con bailarines filmados. Se analizan la respuesta y percepciones del público hacia las transformaciones continuas de los medios tecnológicos de la puesta en escena de la danza. Igualmente, se comparan y contrastan algunos de los debates filosóficos y estéticos de las últimas tres décadas en relación con la danza y el uso de la tecnología en la representación, en particular el referente a la tensión entre la aceptación o rechazo de la falta de «naturalidad» de los cuerpos transducidos y la «naturalidad» de los cuerpos en vivo moviéndose por el espacio escénico. -

Dance Fields Conference Boa NEW

Dance Fields Conference April 19th – 22nd 2017 Book of Abstracts (Chronologically listed) SESSIONSPANELSPRACTICALSWORKSHOPSROUND TABLES Thursday, April 20th 10:00 – 11:30 Session I Chair: Ann R. David Michael Huxley Dance Studies in the UK 1974-1984: A historical consideration of the boundaries of research and the dancer’s voice The first Study of Dance Conference was held at the University of Leeds in 1981. The following year saw the First Conference of British Dance Scholars in London, leading to the inauguration of the Society for Dance Research and then the publication of its journal, Dance Research. Since 1984, the field of dance studies in the UK has both developed and been debated. My paper draws on archival and other sources to reconsider this period historically. With the benefit of current ideas of what constitutes dance, practice, research, and history, it is possible to consider the early years of UK Dance Studies afresh. In the twenty-first-century there are some accepted notions of dance studies. I would argue that they have established boundaries, but that these are often unstated. The period is re-examined with a view to uncovering a broader, and indeed more inclusive, idea of dance studies. In this, attention is given to the researches of practitioners in the period; both published, including in New Dance, and unpublished. Whilst recognising the significant scholarship of the period, the paper also considers the ideas that dancers gave voice to. The analysis is taken further by considering the unexamined discourses that helped enable research in dance in the UK to develop in the way it did. -

1 POPULAR MUSIC in the MERCER ERA, 1910-1970 Building Bridges

1 POPULAR MUSIC IN THE MERCER ERA, 1910-1970 Building Bridges: Hank Williams and the Hit Parade (Draft version submitted November 2010) By Dr. Steve Goodson University of West Georgia Carrollton, GA Hank Williams is widely regarded as the archetypal country music singer, songwriter, and performer. Phenomenally successful during his brief lifetime, he has become -- in the nearly six decades since his death -- something of a national cultural institution. He appeared on a U.S. postage stamp in 1993, he was the focus of a Smithsonian Institution symposium in 1999 – the first country artist to be so honored – and he was the subject of a documentary featured on the PBS American Masters series in 2004. When Mercury Records released a 10-CD compilation of his work – The Complete Hank Williams – the groundbreaking set received substantial reviews from a remarkable array of prestigious mainstream publications, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice, and the Times and the Guardian of London. Fans – most of them too young to remember Williams personally, continue to trek to his grave in his hometown of Montgomery, Alabama, often visiting as well as the city's Hank Williams museum and the nearby Williams statue. Artists continue to record his songs, not only in the country field, but in a variety of genres – Norah Jones and Van Morrison being recent examples. The enduring popularity of and ever-growing esteem – even reverence – for this star- crossed performer are remarkable given that his recording career lasted but six years, and that he did not live to see thirty years of age. -

MASSEY Dave Slreport S17

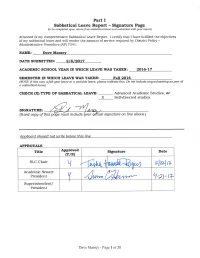

Parts II-V Sabbatical Leave Report II. Re-statement of Sabbatical Leave Application The intention behind this sabbatical proposal is to study contemporary dance forms from internationally and nationally recognized artists in Israel, Europe, and the U.S. The plan is to take daily dance class, week long workshops, to observe dance class and company rehearsals, and interview directors, choreographers, and artists to gain further insight into their movement creation process. This study will benefit my teaching, choreographic awareness, and movement research, which will benefit my students and my department as courses are enhanced by new methodologies, techniques and strategies. The second part of this plan is to visit California colleges and universities to investigate how contemporary dance is being built into their curriculum. Creating a dialogue with my colleagues about this developing dance genre will be important as my department implements contemporary dance into its curriculum. The third part of the sabbatical is to co-produce a dance concert in the San Diego area showcasing choreography that has been created using some of the new methodologies, techniques and strategies founded and discussed while on sabbatical. I will document all hours in a spreadsheet submitted with my sabbatical report. I estimate 580 hours. III. Completion of Objectives, Description of Activities Objective #1: a. To explore, learn, and document best practices in Contemporary Dance b. I started my sabbatical researching contemporary dance and movement. I scoured the web for journals, magazines, videos that gave me insight into how people in dance were talking about this contemporary genre. I also read several books that were thought-provoking about contemporary movement, training and the contemporary dancer. -

The Poetics of Persian Music

The Poetics of Persian Music: The Intimate Correlation between Prosody and Persian Classical Music by Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie B.A., The University of Toronto, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie, 2010 Abstract Throughout most historical narratives and descriptions of Persian arts, poetry has had a profound influence on the development and preservation of Persian classical music, in particularly after the emergence of Islam in Iran. A Persian poetic structure consists of two parts: the form (its fundamental rhythmic structure, or prosody) and the content (the message that a poem conveys to its audience, or theme). As the practice of using rhythmic cycles—once prominent in Iran— deteriorated, prosody took its place as the source of rhythmic organization and inspiration. The recognition and reliance on poetry was especially evident amongst Iranian musicians, who by the time of Islamic rule had been banished from the public sphere due to the sinful socio-religious outlook placed on music. As the musicians’ dependency on prosody steadily grew stronger, poetry became the preserver, and, to a great extent, the foundation of Persian music’s oral tradition. While poetry has always been a significant part of any performance of Iranian classical music, little attention has been paid to the vitality of Persian/Arabic prosody as its main rhythmic basis. Poetic prosody is the rhythmic foundation of the Persian repertoire the radif, and as such it makes possible the development, memorization, expansion, and creation of the complex rhythmic and melodic compositions during the art of improvisation. -

What Are the Overall Benefits of Dance Improvisation, and How Do They Affect Cognition and Creativity? Carley Wright Honors College, Pace University

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 What Are The Overall Benefits of Dance Improvisation, and How Do They Affect Cognition and Creativity? Carley Wright Honors College, Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Cognitive Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Carley, "What Are The Overall Benefits of aD nce Improvisation, and How Do They Affect Cognition and Creativity?" (2018). Honors College Theses. 193. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/193 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What Are The Overall Benefits of Dance Improvisation, and How Do They Affect Cognition and Creativity? Carley Wright BFA Commercial Dance Major Advisor: Jessica Hendricks th nd Presenting: May 7 , Graduating: May 22 Advisor Approval Page Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to define the terms improvisation, cognition, and creativity, and therefore find the direct correlation between all three, and how they can all be involved within dance. The main intention is to determine whether or not improvisational dance can positively influence one’s creative mindset, thus improving the cognitive learning process. Furthermore, it is to discover if the development of a creative mindset can be established through dance improvisation at an early age. In this exploration, the majority of my research will come from the examination of previously conducted experiments, as well as guiding and observing an improvisation class of young adults, gaining insight simply from a dance teacher’s perspective in order to explore the idea of cognition leading to creativity through movement. -

Improvisation Improvisation Theater Facilitation Guide

Improvisation theater facilitation guide Author: Oana Gheorghe 0 CONTENTS IMPROVISATION THEATRE ..................................................................................................... 2 Short history ................................................................................................................................ 2 Principles of Improvisation theater ............................................................................................. 3 IMPROVISATION THEATER - AS A METHOD OF (FORMAL AND NON-FORMAL) EDUCATION ..... 5 Participant and roles .................................................................................................................... 6 Organizing the workshops ........................................................................................................... 8 Who and how does assess? ......................................................................................................... 9 EXAMPLES OF GAMES SPECIFIC TO THIS METHOD ................................................................ 10 Sound ball .................................................................................................................................. 11 Catch and pass ........................................................................................................................... 11 The story of the group ............................................................................................................... 12 Draw according to directions ...................................................................................................