Manual on Material Flow Cost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management and Finance in a “Flat World” Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Bankowej W Poznaniu 2018, T

The WSB University in Poznan Research Journal 2018, Vol. 79, No. 2 Management and Finance in a “Flat World” Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Bankowej w Poznaniu 2018, t. 79, nr 2 Zarządzanie i finanse w „płaskim świecie” redakcja naukowa Wiesława Caputa Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Bankowej w Poznaniu Poznań 2018 The WSB University in Poznan Research Journal 2018, Vol. 79, No. 2 Management and Finance in a “Flat World” edited by Wiesława Caputa The WSB University in Poznan Press Poznan 2018 Komitet wydawniczy / Editorial Board Przewodniczący / Chair: prof. zw. dr hab. Józef Orczyk Członkowie / Members: dr hab. Władysław Balicki, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, dr hab. Arnold Bernaciak, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, dr Piotr Dawidziak, dr hab. Marek Dylewski, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, dr hab. Sławomir Jankiewicz, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, Grażyna Krasowska-Walczak (dyrektor Wydawnictwa WSB w Poznaniu / Director of the WSB University in Poznan Press), dr Alicja Kaiser, dr hab. inż. Tadeusz Leczykiewicz, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, dr hab. Magdalena Majchrzak, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, Andrzej Małecki (sekretarz / Secretary), dr hab. Ilona Romiszewska, prof. WSB w Poznaniu, dr Łukasz Wawrowski, prof. zw. dr hab. Stanisław Wykrętowicz, dr Maria Zamelska Rada naukowa / Scientific Advisory Board prof. dr hab. Przemysław Deszczyński (Polska), dr hab. Marek Dylewski, prof. WSB w Poznaniu (Polska), prof. dr hab. Beata Filipiak (Polska), dr hab. inż. Tadeusz Leczykiewicz, prof. WSB w Poznaniu (Polska), prof. dr hab. Jan Szambelańczyk (Polska), doc. Ing. Emília Zimková PhD (Słowacja), doc. Ing. Peter Krištofík PhD (Słowacja), prof. Sergiy Gerasymenko DSc (Ukraina), prof. dr Bernt Mayer (Niemcy), prof. dr Franz Seitz (Niemcy), prof. J. -

ISO 26000:2010 (Traducción Oficial) © ISO 2010 ISO 26000:2010 (Traducción Oficial)

NORMA ISO INTERNACIONAL 26000 Traducción oficial Official translation Primera edición 2010-11-01 Traduction officielle Guía de responsabilidad social Guidance on social responsibility Lignes directrices relatives à la responsabilité sociétale Publicado por la Secretaría Central de ISO en Ginebra, Suiza, como traducción oficial en español avalada por el Translation Management Group, que ha certificado la conformidad en relación con las versiones inglesa y francesa. Número de referencia ISO 26000:2010 (traducción oficial) © ISO 2010 ISO 26000:2010 (traducción oficial) PDF – Exoneración de responsabilidad El presente fichero PDF puede contener pólizas de caracteres integradas. Conforme a las condiciones de licencia de Adobe, este fichero podrá ser impreso o visualizado, pero no deberá ser modificado a menos que el ordenador empleado para tal fin disfrute de una licencia que autorice la utilización de estas pólizas y que éstas estén instaladas en el ordenador. Al descargar este fichero, las partes implicadas aceptan de hecho la responsabilidad de no infringir las condiciones de licencia de Adobe. La Secretaría Central de ISO rehusa toda responsabilidad sobre esta cuestión. Adobe es una marca registrada de Adobe Systems Incorporated. Los detalles relativos a los productos software utilizados para la creación del presente fichero PDF están disponibles en la sección General Info del fichero. Los parámetros de creación PDF han sido optimizados para la impresión. Se han adoptado todas las medidas pertinentes para garantizar la explotación de este fichero por los comités miembros de ISO. En la eventualidad poco probable de surgir un problema de utilización, sírvase comunicarlo a la Secretaría Central en la dirección indicada a continuación. -

Environmental Management - Vocabulary รายละเอียดใหเปนไปตามมาตรฐาน ISO 14051 : 2011 ขอ 2

หน้า ๑๑ เล่ม ๑๓๐ ตอนพิเศษ ๑๘๘ ง ราชกิจจานุเบกษา ๒๔ ธันวาคม ๒๕๕๖ ประกาศกระทรวงอุตสาหกรรม ฉบับที่ ๔๕๘๒ (พ.ศ. ๒๕๕๖) ออกตามความในพระราชบัญญัติมาตรฐานผลิตภัณฑ์อุตสาหกรรม พ.ศ. ๒๕๑๑ เรื่อง กําหนดมาตรฐานผลิตภัณฑ์อุตสาหกรรม การจัดการสิ่งแวดล้อม : บัญชีต้นทุนการไหลของวัสดุ : กรอบทั่วไป อาศัยอํานาจตามความในมาตรา ๑๕ แห่งพระราชบัญญัติมาตรฐานผลิตภัณฑ์อุตสาหกรรม พ.ศ. ๒๕๑๑ รัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงอุตสาหกรรมออกประกาศกําหนดมาตรฐานผลิตภัณฑ์อุตสาหกรรม การจัดการสิ่งแวดล้อม : บัญชีต้นทุนการไหลของวัสดุ : กรอบทั่วไป มาตรฐานเลขที่ มอก.14051 - 2556 ไว้ ดังมีรายการละเอียดต่อท้ายประกาศนี้ ทั้งนี้ ให้มีผลตั้งแต่วันประกาศในราชกิจจานุเบกษาเป็นต้นไป ประกาศ ณ วันที่ ๔ พฤศจิกายน พ.ศ. ๒๕๕๖ ประเสริฐ บุญชัยสุข รัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงอุตสาหกรรม มอก. 14051-2556 ISO 14051 : 2011 (E) มาตรฐานผลิตภัณฑอุตสาหกรรม การจัดการสิ่งแวดลอม : บัญชีตนทุนการไหลของวัสดุ : กรอบทั่วไป 0. บทนํา มาตรฐานนี้มีจุดมุงหมายเพื่อเสนอกรอบในการจัดทําบัญชีตนทุนการไหลของวัสดุ ซึ่งเปนเครื่องมือการจัดการที่ ชวยใหองคกรเกิดความเขาใจมากขึ้นเกี่ยวกับการใชวัสดุและพลังงานที่จะมีผลตอไปถึงเรื่องสิ่งแวดลอมและการเงิน และชวยแสวงหาโอกาสที่จะปรับปรุงสิ่งแวดลอมและการเงินจากการเปลี่ยนแปลงวิธีการปฏิบัติงานดังกลาว บัญชีตนทุนการไหลของวัสดุชวยสงเสริมการใชวัสดุและพลังงานใหมีความโปรงใสมากขึ้นโดยผานการพัฒนา แบบจําลองการไหลของวัสดุที่มีการติดตามและวัดปริมาณการไหลของวัสดุและวัสดุคงเหลือขององคกรนับเปน หนวยทางกายภาพ พลังงานสามารถนับรวมเปนวัสดุหรือแยกรายงานเชิงปริมาณตางหากโดยวิธีใดวิธีหนึ่งในบัญชี ตนทุนการไหลของวัสดุ ตนทุนตาง ๆ ที่เกิดขึ้นและ/หรือ ที่เกี่ยวของกับวัสดุและพลังงานตองมีการรายงานเชิง ปริมาณตามการไหลเหลานั้นโดยเฉพาะมาตรฐานเนนการเปรียบเทียบตนทุนที่เกี่ยวของกับผลิตภัณฑและตนทุน -

2012-01 (Adobe Reader)

Turinys STANDARTIZACIJA ........................................................................................ 5 IÐLEISTI LIETUVOS STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI ............................................ 5 NETEKÆ GALIOS LIETUVOS STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI ............................. 15 NETEKSIANTYS GALIOS LIETUVOS STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI ................. 19 SIÛLOMA SKELBTI NETEKSIANÈIAIS GALIOS ORIGINALIUOSIUS LIETUVOS STANDARTUS .................................................................................. 20 TARPTAUTINIØ IR EUROPOS ÁSTAIGØ BEI ORGANIZACIJØ STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI, KURIUOS DEPARTAMENTAS GAVO GRUODÞIO MËN. ....... 21 TARPTAUTINËS STANDARTIZACIJOS ORGANIZACIJOS STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI .................. 21 TARPTAUTINËS ELEKTROTECHNIKOS KOMISIJOS STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI ...................... 27 RATIFIKUOTI EUROPOS STANDARTIZACIJOS KOMITETO STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI ............... 28 RATIFIKUOTI EUROPOS ELEKTROTECHNIKOS STANDARTIZACIJOS KOMITETO STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI .................................................................................................. 32 RATIFIKUOTI EUROPOS TELEKOMUNIKACIJØ STANDARTØ INSTITUTO STANDARTAI IR KITI LEIDINIAI .................................................................................................. 33 REDAKCINË KOLEGIJA Redagavo A. Treèiokaitë Maketavo A. Skomskienë 2012-01-09 © Lietuvos standartizacijos departamentas, 2012 Lietuvos standartizacijos departamento BIULETENIS 2012 Nr. 1 VILNIUS, 2012 Lietuvos standartizacijos departamentas -

Dutch Data Center Standards Guide a Dynamic Document to Provide an Overview of All Data Center Standards

— Dutch data center 2020 Standards guide Why data center standards are key for quality, sustainability and time to market while maintaining continuous growth in digitisation Content 1 The digital economy is the economy 2 Data Center standards 3 Dutch DC standards breakdown and drilldown - Appendices; about, further reading, colophon About Dutch Data Center Standards Guide A dynamic document to provide an overview of all data center standards The purpose of this Dutch Data Center Standards Guide is to provide a good summary of the available standards concerning Data Centers with a special focus on the Netherlands. This is a dynamic guide which will be continually edited and updated. We also realise that this document is far from complete and it is our goal to expand this document in time. This is the first version of this guide and was published January 2020. We are open to any remarks, corrections and suggestions. If you have any please do contact us via the email [email protected]. THE DIGITAL ECONOMY IS 1. THE ECONOMY 1. Everything is data driven Everything is data driven The world is rapidly changing due to digital transformation 1. The digital economy is the economy More and more revenue through digitisation: top priority to go along with By 2022, more than 60% of global GDP1 will be digitized with growth in every industry, driven by digitally enhanced offers, operations and relationships. Management of each organisation must place digital transformation at the top of their priority list. All that happens online originates from data centers. Figure: Digital Economy Model - DDA, DHPA, ISPConnect, The METISfiles, 2020 1. -

Lista Mensal De Julho 2011

Publicação oficial do IPQ, enquanto Organismo Nacional de Normalização lista mensal julho 2011 A presente -publicação tem por objectivo : - A divulgação das Normas Portuguesas recentemente editadas e anuladas, bem como das Normas Europeias ad optadas como Normas Portuguesas, e das Normas Europeias e Internacionais publicadas e já disponíveis. - A divulgação pública dos projectos de Normas Portuguesas, Europeias e Internacionais, com vista à obtenção durante o período de inquérito público dos p ontos de vista e contribuições nacionais que possam ser considerados na sequente elaboração, aprovação e homologação das Normas. - A divulgação de propostas de novos trabalhos de normalização europeia e internacional, para que se possa obter, durante o período de inquérito público, os pontos de vista e as contribuições nacionais. - A divulgação da edição e anulação de outros documentos normativos. ÍNDICE 1. Normas Portuguesas 1.1 Normas Portuguesas publicadas ……………………………………………………………………….3 1.2 Normas Portuguesas anuladas ………………………………………………………………………….5 1.3 Normas Portuguesas em re -exame ………………………………………………………………….…7 1.4 Normas Europeias adoptadas …………………………………………………………………………..8 2. Normas Europeias Publicadas 2.1 CEN …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 2.2 CENELEC ……………………………………………………………………………………………………13 2.3 CEN/CENELEC ……………………………………………………………………………………….…….15 2.4 ETSI ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 3. Normas Internacionais publicadas IEC ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17 ISO 18 4. Projectos de normas portuguesas 4.1 -

Rohail Hassan

ROHAIL HASSAN Senior Lecturer Ph.D. in Management Othman Yeop Abdullah Graduate School of Business (OYAGSB) Universiti Utara Malaysia (Northern University of Malaysia) 06010 UUM Sintok, Kedah Darul Aman Malaysia. Office Address: Office No. 2.19, OYAGSB, UUM, Malaysia. Personal Mobile: +60 11 1641 6168 Official Number: +604 928 7127 Official Email: [email protected] Personal Email: [email protected] Personal Website: http://rohailhasan.wix.com/rohail Official Webpage: https://bit.ly/2mBt9XM ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION 2013 - 2018 Ph.D. in Management, Department of Management & Humanities, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Malaysia. Dissertation Title: “Corporate Board Diversity and its Implications on Firm Financial Performance: An Empirical Investigation on Listed Companies in Malaysia.” 2010 - 2012 MS/MPhil in Total Quality Management (TQM), Institute of Quality & Technology Management, University of The Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. Dissertation Title: “Application of Six Sigma for Process Improvement in Pakistan Ordinance Factory Wah Cantt” 2006 - 2010 BS (HONS) in Management, Institute of Administrative Sciences, University of The Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. Dissertation Title: “Mutual Funds in Pakistan” RESEARCH INTERESTS Diversity and Inclusion, Gender Diversity, Firm Performance, Institutional Ownership, Corporate Governance, Mergers and Acquisitions, Corporate Strategy, Accounting, Financial Management, Strategic Management, CSR and Business Ethics, Sustainability, Computer Science and IT, SCM, Six Sigma, Total Quality Management, -

Maturity Model Concepts for Sustainable Manufacturing

NISTIR 7989 Maturity Model Concepts for Sustainable Manufacturing Sanjay Jain Sudarsan Rachuri http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.7989 NISTIR 7989 Maturity Model Concepts for Sustainable Manufacturing Sanjay Jain The George Washington University Washington, DC Sudarsan Rachuri Systems Integration Division Engineering Laboratory http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.7989 March 2014 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology and Director Maturity Model Concepts for Sustainable Manufacturing Abstract: Sustainability has been identified as an emerging business megatrend that companies across the spectrum need to respond to. Companies in the manufacturing industry have also increased their efforts in this direction. However, the efforts for improving the efficiency of manufacturing processes vary widely across the industry and may vary even within different locations of a large manufacturing organization. This paper reviews major initiatives and research relevant to developing and providing guidance for organizations interested in sustainable manufacturing. A concept is proposed for a maturity model to assist manufacturers with understanding the status of their efforts for sustainable manufacturing specifically focusing on materials, energy, and water use. The concept is being presented to gather inputs from relevant stakeholders and for further development into a model that provides high-level guidance to manufacturers for improving sustainability of their operations. 1. INTRODUCTION Sustainability has been identified as an emerging business megatrend that companies need to address to stay competitive and maybe, to even survive (Lubin and Esty, 2010). There are efforts across the globe to implement green manufacturing and achieve sustainable manufacturing (Dornfeld, 2014). -

Standards Available in Electronic Format (PDF) Page 1

Standards available in electronic format (PDF) August 2019 SANS Number Edition Title SANS 1-2:2013 2 Standard for standards Part 2: Recognition of Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) in South Africa SATS 2:2012 1 The development of normative documents other than South African National Standards SANS 2:2013 7.01 Lead-acid starter batteries (SABS 2) SANS 4:2008 3.03 Locks, latches, and associated furniture for doors (SABS 4) (Domestic Type) SANS 11:2007 1.02 Unplasticized poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC-U) (SABS 11) components for external rainwater systems SANS 13:2008 2.03 Wax polish, solvent-based, for floors and furniture (SABS 13) SANS 14:1994/ISO 49:1994, IDT, Ed. 2 1 Malleable cast iron fittings threaded to ISO 7-1 (SABS ISO 49) SANS 15:2008 2.03 Wax emulsion polish for floors and furniture (SABS 15) SANS 16:2007/ISO/IEC 10116:2006, IDT, Ed. 3 2 Information technology - Security techniques - Modes of operation for an n-bit block cipher SANS 17:2014 1.01 Glass and plastics in furniture SANS 18-1:2003/ISO/IEC 10118-1:2000, IDT, Ed. 2 1 Information technology - Security techniques - Hash- functions Part 1: General SANS 18-2:2011/ISO/IEC 10118-2:2010, IDT, Ed. 3 2 Information technology - Security techniques - Hash- functions Part 2: Hash-functions using an n-bit block cipher SANS 18-3:2007/ISO/IEC 10118-3:2004, IDT, Ed. 3 2 Information technology - Security techniques - Hash- functions Part 3: Dedicated hash-functions SANS 18-4:2003/ISO/IEC 10118-4:1998, IDT, Ed. -

Environmental and Sustainability Management Accounting Network

business solutions for a sustainable world Environmental and Sustainability Management Accounting Network International Sustainability Accounting Symposium 2015 Measuring sustainability performance: bridging corporate and academic contributions Reporting Exchange VERGE Reporting Together Reporting Exchange terminus Reporting Reporting Exchange Exchange reporting Reporting terminusHelping shape the reporting landscape. together Xchange Reporting embark Disclosure Proceedings of the first WBCSD and EMAN joint international sustainability accounting symposium, Geneva, 2015 2 Contents Content and scope of sustainability accounting 6 Natural capital accounting - Bande & Debecker: Sustainable Portfolio Management (SPM) approach at Solvay to decision 7 making and strategy development - Houdet & Mnguni: Net impact accounting and reporting in the mining sector: Bridging the gap 9 between discourse and disclosed information in South Africa - Gough, Zabey & Pitts: Bridging the gap between business and nature: Introducing the Natural 11 Capital Protocol - Prox, Sonnemann & Strothmann: Environmental Management Accounting and Life Cycle 13 Assessment – separate worlds with a strong potential to team up for measuring corporate sustainability performance Social capital accounting - Dietz: Social capital and decision making 16 - Wessels, Shandler & McNulty: Learning by doing - A sustainable development outcome 24 measurement methodology for a South African company - Williams: Aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals: Implications for measuring -

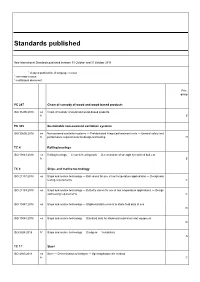

Standards Confirmed

Standards published New International Standards published between 01 October and 31 October 2018 1 delayed publication of language version 2 corrected version 3 multilingual document Price group PC 287 Chain of custody of wood and wood-based products ISO 38200:2018 en Chain of custody of wood and wood-based products fr E PC 305 Sustainable non-sewered sanitation systems ISO 30500:2018 en Non-sewered sanitation systems — Prefabricated integrated treatment units — General safety and fr performance requirements for design and testing H TC 4 Rolling bearings ISO 19843:2018 en Rolling bearings — Ceramic bearing balls — Determination of strength by notched ball test fr E TC 8 Ships and marine technology ISO 21157:2018 en Ships and marine technology — Ball valves for use in low temperature applications — Design and testing requirements C ISO 21159:2018 en Ships and marine technology — Butterfly valves for use in low temperature applications — Design and testing requirements C ISO 19847:2018 en Ships and marine technology — Shipboard data servers to share field data at sea G ISO 19848:2018 en Ships and marine technology — Standard data for shipboard machinery and equipment G ISO 8384:2018 fr1 Ships and marine technology — Dredgers — Vocabulary A TC 17 Steel ISO 4945:2018 en Steel — Determination of nitrogen — Spectrophotometric method fr C ISO 683-3:2016 fr1 Heat-treatable steels, alloy steels and free-cutting steels — Part 3: Case-hardening steels E ISO 13520:2015 fr1 Determination of ferrite content in austenitic stainless steel castings B ISO -

Standards Published in 2011

IRISH STANDARDS PUBLISHED BASED ON CEN/CENELEC STANDARDS 1. I.S. EN 152-2:1988/AC1:1989 Date published 11 APRIL 2011 Test methods for wood preservatives. Laboratory method for determining the protective effectiveness of a preservative treatment against blue stain in service. Part 2 : Application by methods other than brushing. 2. S.R. CR 1350:1993 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Investigation of Syntaxes for Existing Interchange Formats to be Used in Healthcare 3. S.R. CR 1460:1994 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Packaging – Energy Recovery from Used Packaging 4. S.R. CR 12161:1995 Date published 24 SEPTEMBER 2011 A method for defining profiles for healthcare 5. S.R. CR 12340:1996 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Packaging - Recommendations for conducting life-cycle inventory analysis of packaging systems 6. S.R. CR 1901:1995 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Regional Specifications and Recommendations for the avoidance of damaging alkali silica reactions in concrete 7. S.R. CR 12776:1997 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Copper and copper alloys - Provisions and procedures for the allocation of material numbers and registration of materials 8. S.R. CR 12793:1997 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Measurement of the carbonation depth of hardened concrete 9. S.R. CR 12804:1997 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Conceptual Model and Taxonomy for Information Systems Engineering 10. S.R. CR 12894:1997 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Biotechnology - Microorganisms - Examination of the various existing lists of animal pathogens and production of a report 11. S.R. CR 13156:1998 Date published 21 SEPTEMBER 2011 Some occupational profiles for practitioners in logistics 12.