Thoracic Trauma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study

SPINE Volume 31, Number 4, pp 451–458 ©2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study Allan D. Levi, MD, PhD,* R. John Hurlbert, MD, PhD,† Paul Anderson, MD,‡ Michael Fehlings, MD, PhD,§ Raj Rampersaud, MD,§ Eric M. Massicotte, MD,§ John C. France, MD, Jean Charles Le Huec, MD, PhD,¶ Rune Hedlund, MD,** and Paul Arnold, MD†† Study Design. A retrospective study was undertaken their neurologic injury. The most common reason for the that evaluated the medical records and imaging studies of missed injury was insufficient imaging studies (58.3%), a subset of patients with spinal injury from large level I while only 33.3% were a result of misread radiographs or trauma centers. 8.3% poor quality radiographs. The incidence of missed Objective. To characterize patients with spinal injuries injuries resulting in neurologic injury in patients with who had neurologic deterioration due to unrecognized spine fractures or strains was 0.21%, and the incidence as instability. a percentage of all trauma patients evaluated was 0.025%. Summary of Background Data. Controversy exists re- Conclusions. This multicenter study establishes that garding the most appropriate imaging studies required to missed spinal injuries resulting in a neurologic deficit “clear” the spine in patients suspected of having a spinal continue to occur in major trauma centers despite the column injury. Although most bony and/or ligamentous presence of experienced personnel and sophisticated im- spine injuries are detected early, an occasional patient aging techniques. Older age, high impact accidents, and has an occult injury, which is not detected, and a poten- patients with insufficient imaging are at highest risk. -

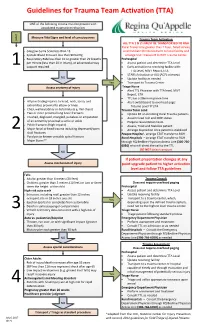

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

Fat Embolism Syndrome – a Qualitative Review of Its Incidence, Presentation, Pathogenesis and Management

2-RA_OA1 3/24/21 6:00 PM Page 1 Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal 2021 Vol 15 No 1 Timon C, et al doi: https://doi.org/10.5704/MOJ.2103.001 REVIEW ARTICLE Fat Embolism Syndrome – A Qualitative Review of its Incidence, Presentation, Pathogenesis and Management Timon C, MCh, Keady C, MSc, Murphy CG, FRCS Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Galway University Hospitals, Galway, Ireland This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited Date of submission: 12th November 2020 Date of acceptance: 05th March 2021 ABSTRACT DEFINITION AND INTRODUCTION Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES) is a poorly defined clinical Fat embolism 1 occurs when fat enters the circulation, this fat phenomenon which has been attributed to fat emboli entering can embolise and may or may not produce clinical the circulation. It is common, and its clinical presentation manifestations. may be either subtle or dramatic and life threatening. This is a review of the history, causes, pathophysiology, FES is a poorly defined clinical phenomenon which has been presentation, diagnosis and management of FES. FES mostly attributed to fat emboli entering the circulation. It classically occurs secondary to orthopaedic trauma; it is less frequently presents with respiratory, neurological and dermatological associated with other traumatic and atraumatic conditions. features. It typically occurs after long-bone fractures and There is no single test for diagnosing FES. Diagnosis of FES total hip arthroplasty, less frequently it is caused by burns is often missed due to its subclinical presentation and/or and soft tissue injuries 2. -

UHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelines 2014

Adult Major Trauma Guidelines University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust Version 1.1 Dr Andy Eynon Director of Major Trauma, Consultant in Neurosciences Intensive Care Dr Simon Hughes Deputy Director of Major Trauma, Consultant Anaesthetist Dr Elizabeth Shewry Locum Consultant Anaesthetist in Major Trauma Version 1 Dr Andy Eynon Dr Simon Hughes Dr Elizabeth ShewryVersion 1 1 UHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelines 2014 NOTE: These guidelines are regularly updated. Check the intranet for the latest version. DO NOT PRINT HARD COPIES Please note these Major Trauma Guidelines are for UHS Adult Major Trauma Patients. The Wessex Children’s Major Trauma Guidelines may be found at http://staffnet/TrustDocsMedia/DocsForAllStaff/Clinical/Childr ensMajorTraumaGuideline/Wessexchildrensmajortraumaguid eline.doc NOTE: If you are concerned about a patient under the age of 16 please contact SORT (02380 775502) who will give valuable clinical advice and assistance by phone to the Trauma Unit and coordinate any transfer required. http://www.sort.nhs.uk/home.aspx Please note current versions of individual University Hospital South- ampton Major Trauma guidelines can be found by following the link below. http://staffnet/TrustDocuments/Departmentanddivision- specificdocuments/Major-trauma-centre/Major-trauma-centre.aspx Version 1 Dr Andy Eynon Dr Simon Hughes Dr Elizabeth Shewry 2 UHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelines 2014 Contents Please ‘control + click’ on each ‘Section’ below to link to individual sections. Section_1: Preparation for Major Trauma Admissions -

Anytown Trauma Center Trauma Protocols

ANYTOWN TRAUMA CENTER TRAUMA PROTOCOLS TITLE: TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTOCOL PURPOSE: The purpose of the protocol is to establish guidelines for trauma team activation and define the members of the responding trauma team to facilitate the resuscitation and management of critical or seriously injured patients who require rapid, organized resuscitation, evaluation and stabilization to promote optimal outcomes. It also serves to provide triage guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. PROCESS: 1. TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTCOL A. The criteria for activation of the trauma team is clearly defined and posted at the Emergency Department triage desk, by the EMS communication station and in the resuscitation rooms. B. The trauma team may be activated prior to arrival based on the EMS communication and their assessment. C. The trauma surgeon, emergency medicine physician, emergency department charge nurse/ house supervisor, emergency department nurses and the Trauma Program Manager may activate the trauma team. D. The person calling the trauma activation will initiate the trauma page to group page the trauma team and will specify the MOI, BP, HR, ETA and level of activation required and age if available. E. If the trauma team members are present in the emergency department and alert is still communicated to ensure everyone is notified. F. Trauma team member notification and arrival times will be documented on the trauma flow sheet (paper or electronic). G. Trauma team members will sign-in when they arrive. H. Trauma team members will be activated for all patients who meet the following criteria: 1. Level 1 trauma activation (major): life threatening injuries and/or unstable vital signs, limb-threating or disability threatening injury 2. -

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital through the Emergency Department Test Questions 1. As the prehospital provider approaches the scene of a trauma call, they perform a. a radio transmission to the hospital b. a scene size up c. an estimate of neck size for c-collar d. an estimate of victim’s height and weight 2. Field intubation has been proven to improve outcome in a. patients with BP less than 90 mm Hg b. patients with GCS less than 9 c. patients with acute respiratory distress d. none of the above 3. A proven technique of hemorrhage control is a. Direct pressure b. Elevate above the heart c. Pressure points d. Cold application 4. Prehospital care for apparent pelvic fractures includes a. DO NOT ROCK or palpate the pelvis in the prehospital arena b. Avoid log rolling as much as possible c. Apply splint if in your area protocols d. All of the above 5. Most preventable deaths in trauma care are due to a. Delay in CPR b. Cardiac tamponade c. Airway obstruction d. Tension pneumothorax STN 2012 Electronic Library: Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions 2 6. For resuscitation to occur, there must be a. Cellular perfusion and tissue oxygenation b. Restoration of a blood pressure greater than 90mm Hg c. A hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL d. A PaO2 greater than 80 mm Hg 7. The Trauma Triad of Death is a. Hypotension, tachycardia and decreased urine output b. Infection, inadequate nutrition, DVT’s c. Hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy d. -

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 4Th Edition

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 4th Edition Nancy Carney, PhD Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Annette M. Totten, PhD Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Cindy O'Reilly, BS Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Jamie S. Ullman, MD Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Hempstead, NY Gregory W. J. Hawryluk, MD, PhD University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Michael J. Bell, MD University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Susan L. Bratton, MD University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Randall Chesnut, MD University of Washington, Seattle, WA Odette A. Harris, MD, MPH Stanford University, Stanford, CA Niranjan Kissoon, MD University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC Andres M. Rubiano, MD El Bosque University, Bogota, Colombia; MEDITECH Foundation, Neiva, Colombia Lori Shutter, MD University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Robert C. Tasker, MBBS, MD Harvard Medical School & Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Monica S. Vavilala, MD University of Washington, Seattle, WA Jack Wilberger, MD Drexel University, Pittsburgh, PA David W. Wright, MD Emory University, Atlanta, GA Jamshid Ghajar, MD, PhD Stanford University, Stanford, CA Reviewed for evidence-based integrity and endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. September 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................. -

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC Dale Dangleben, MD, FACS 1 2 Team 3 Extended Team 4 Team Leader Decrease chaos / optimize care. – Remains calm – Maintains control and provides direction – Stays decisive – Sees the big picture (situational awareness) – Is open to other team members input – Directs resuscitation – Makes early decision to transfer the patients that exceed the local capabilities 5 Team Members − Know your roles in the trauma team − Remain calm − Be responsive to team leader −Voice suggestions or concerns 6 Responsibilities – Perform the Primary and secondary survey – Verbalize patient care – Report completed tasks 7 Responsibilities – Monitors the patient – Manual BP – Obtains IV access – Administers medications – Dresses wounds – Performs or assists in resuscitative procedures 8 Responsibilities Records data Ensures documentation accompanies patient upon transfer Assists team members as needed 9 Responsibilities – Obtains needed supplies – Coordinates communication with local and external resources – Assists team members as needed 10 Responsibilities • Place Oxygen on patient • Manage airway • Hold C spine • Manage ventilator if • Manage rapid infuser line patient intubated where indicated • Assists team members as needed 11 Organization of trauma resuscitation area – Basic adult and pediatric equipment for: • Airway management (cart) • IV access with warm fluids • Chest tube insertion • Hemorrhage control (tourniquets, pelvic binders) • Immobilization • Medications • Pediatric length/weight based tape (Broselow Tape) – Warming -

Incidence of Fat Embolism Syndrome in Femur Fractures and Its Associated Risk Factors Over Time—A Systematic Review

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Incidence of Fat Embolism Syndrome in Femur Fractures and Its Associated Risk Factors over Time—A Systematic Review Maximilian Lempert 1,* , Sascha Halvachizadeh 1 , Prasad Ellanti 2, Roman Pfeifer 1, Jakob Hax 1, Kai O. Jensen 1 and Hans-Christoph Pape 1 1 Department of Trauma, University Hospital Zurich, Raemistr. 100, 8091 Zürich, Switzerland; [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (R.P.); [email protected] (J.H.); [email protected] (K.O.J.); [email protected] (H.-C.P.) 2 Department of Trauma and Orthopedics, St. James’s Hospital, Dublin-8, Ireland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-44-255-27-55 Abstract: Background: Fat embolism (FE) continues to be mentioned as a substantial complication following acute femur fractures. The aim of this systematic review was to test the hypotheses that the incidence of fat embolism syndrome (FES) has decreased since its description and that specific injury patterns predispose to its development. Materials and Methods: Data Sources: MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases were searched for articles from 1 January 1960 to 31 December 2019. Study Selection: Original articles that provide information on the rate of FES, associated femoral injury patterns, and therapeutic and diagnostic recommendations were included. Data Extraction: Two authors independently extracted data using a predesigned form. Statistics: Three different periods were separated based on the diagnostic and treatment changes: Group 1: 1 January 1960–12 December 1979, Group 2: 1 January 1980–1 December 1999, and Group 3: 1 January 2000–31 December 2019, chi-square test, χ2 test for group comparisons of categorical Citation: Lempert, M.; p n Halvachizadeh, S.; Ellanti, P.; Pfeifer, variables, -value < 0.05. -

Spinal Cord Injury Cord Spinal on Perspectives International

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES ON SPINAL CORD INJURY “Spinal cord injury need not be a death sentence. But this requires e ective emergency response and proper rehabilitation services, which are currently not available to the majority of people in the world. Once we have ensured survival, then the next step is to promote the human rights of people with spinal cord injury, alongside other persons with disabilities. All this is as much about awareness as it is about resources. I welcome this important report, because it will contribute to improved understanding and therefore better practice.” SHUAIB CHALKEN, UN SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON DISABILITY “Spina bi da is no obstacle to a full and useful life. I’ve been a Paralympic champion, a wife, a mother, a broadcaster and a member of the upper house of the British Parliament. It’s taken grit and dedication, but I’m certainly not superhuman. All of this was only made possible because I could rely on good healthcare, inclusive education, appropriate wheelchairs, an accessible environment, and proper welfare bene ts. I hope that policy-makers everywhere will read this report, understand how to tackle the challenge of spinal cord injury, and take the necessary actions.” TANNI GREYTHOMPSON, PARALYMPIC MEDALLIST AND MEMBER OF UK HOUSE OF LORDS “Disability is not incapability, it is part of the marvelous diversity we are surrounded by. We need to understand that persons with disability do not want charity, but opportunities. Charity involves the presence of an inferior and a superior who, ‘generously’, gives what he does not need, while solidarity is given between equals, in a horizontal way among human beings who are di erent, but equal in their rights. -

Trauma Resuscitation and the Damage Control Approach

SURGERY FOR MAJOR INCIDENTS anatomy’). This philosophy has increasingly been adopted in the Trauma resuscitation and the civilian environment. DCS describes the specific, systematic surgical approaches damage control approach focussing on normalizing physiology from the dual insults of injury and surgery, as opposed to providing immediate definitive Nathan West repair.3,4 DCRad incorporates diagnostic and interventional Rob Dawes radiological solutions used to treat severely injured patients.5 Recent history of trauma care Abstract Haemorrhage remains the biggest killer of major trauma patients. One- Advances in trauma care commonly occur during warfare, where third of trauma patients are coagulopathic on admission, which is exacer- high numbers of seriously injured soldiers are treated, although a bated further by other factors. Failure to address this results in poor out- landmark change was the introduction of the Advanced Trauma Ò comes. Damage control resuscitation is current best practice for bleeding Life Support (ATLS) programme in 1978. ATLS was originally trauma patients, and encompasses damage control surgery and damage targeted at doctors with little expertise in trauma and provides a control radiography. This review provides a summary of the latest con- structured system for recognizing life-threatening problems and cepts in the rapidly evolving field of trauma resuscitation management. instigating appropriate interventions. The ATLS ‘Airway, Keywords Damage control; massive haemorrhage; resuscitation; trauma Breathing, Circulation, Disability, and Exposure’ (ABCDE) mantra is familiar the world over. Whilst it is likely this approach has saved many lives over the years, with the advent of regional Introduction trauma networks and experience gained from large recent mili- tary campaigns, an approach that reaches beyond ATLS is now Damage control (DC) was first termed to describe measures required in civilian practice.