The Texas Property Tax System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

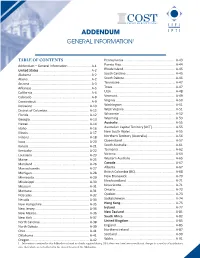

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Itep Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes: About Iii

THE GUIDE TO Fair State and Local Taxes 2011 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy 1616 P Street, NW, Suite 201, Washington, DC 20036 | 202-299-1066 | www.itepnet.org | [email protected] THE ITEP GUIDE TO FAIR STATE AND LOCAL TAXES: ABOUT III About the Guide The ITEP Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes is designed to provide a basic overview of the most important issues in state and local tax policy, in simple and straightforward language. The Guide is also available to read or download on ITEP’s website at www.itepnet.org. The web version of the Guide includes a series of appendices for each chapter with regularly updated state-by-state data on selected state and local tax policies. Additionally, ITEP has published a series of policy briefs that provide supplementary information to the topics discussed in the Guide. These briefs are also available on ITEP’s website. The Guide is the result of the diligent work of many ITEP staffers. Those primarily responsible for the guide are Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner, Jeff McLynch, and Meg Wiehe. The Guide also benefitted from the valuable feedback of researchers and advocates around the nation. Special thanks to Michael Mazerov at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. About ITEP Founded in 1980, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) is a non-profit, non-partisan research organization, based in Washington, DC, that focuses on federal and state tax policy. ITEP’s mission is to inform policymakers and the public of the effects of current and proposed tax policies on tax fairness, government budgets, and sound economic policy. -

2018 Personal Tax Guide and Tax Tips for 2017

2018 personal tax guide and tax tips for 2017 Featuring coverage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 EisnerAmper LLP Accountants and Advisors www.eisneramper.com INTRODUCTION: 2018 IS A YEAR OF CHANGE In 2017, we were subject to the tax regime resulting from the before January 1, 2026. All miscellaneous itemized deductions American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (“ATRA”): The top federal that are subject to the 2% AGI limit are repealed for tax years ordinary income tax rate was at 39.6%, the top federal long-term 2018-2025. Home mortgage interest expense is limited to interest capital gains tax was at 20% and the top alternative minimum tax on acquisition debt for tax years 2018-2025, with the maximum rate was at 28%. The top estate and gift tax rate was at 40% and amount that may be treated as acquisition debt reduced to a $5.49 million gift, estate and generation-skipping tax exclusion $750,000 (from $1 million) and applied to any acquisition debt was in effect. incurred after December 15, 2017. The $1 million threshold is reinstated starting in 2026. Interest paid on home equity debt In addition, the enactment of the Protecting Americans from Tax of any qualified residence is not deductible except for loans used Hikes Act of 2015 (“PATH”) extended many of the tax incentives and to buy, build or substantially improve the taxpayer’s home that credits for individuals and businesses—some on a permanent basis. secures the loan. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) continued to impose a 0.9% Health Insurance Tax on earned income for • Charitable deductions remain a viable itemized deduction. -

Qualifying the Homestead Exemption As a Federal Estate Tax Marital Deduction

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 13 Number 2 Winter 1979 pp.343-381 Winter 1979 Qualifying the Homestead Exemption as a Federal Estate Tax Marital Deduction Louis D. Fisher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Louis D. Fisher, Qualifying the Homestead Exemption as a Federal Estate Tax Marital Deduction, 13 Val. U. L. Rev. 343 (1979). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol13/iss2/5 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Fisher: Qualifying the Homestead Exemption as a Federal Estate Tax Marita QUALIFYING THE HOMESTEAD EXEMPTION AS A FEDERAL ESTATE TAX MARITAL DEDUCTION INTRODUCTION One goal of effective estate planning is to keep the final estate taxes as low as possible. Keeping assets out of the estate will ac- complish this goal. On the other hand, exempting included assets from estate tax computations reduces the base on which a tax is computed. For a married couple, the marital deduction is a common deduction from the gross estate of the first spouse to die.' Although the most common source of assets for qualification under the marital deduction is property bequeathed to a surviving spouse, the use of statutory exemptions and allowances provided by various state statutes furnishes a second source of qualification. The statutory interest addressed in this note is the homestead exemption. -

Bulletin No. 13 (Motor Vehicle Excise Tax & Personal Property Tax)

MAINE REVENUE SERVICES PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NO. 13 MOTOR VEHICLE EXCISE TAX & PERSONAL PROPERTY TAX REFERENCE: 36 M.R.S. §§ 1481 through 1491 December 9, 2019; replaces November 21, 2017 revision 1. General The motor vehicle excise tax is an annual tax imposed for the privilege of operating a motor vehicle on public roads. This bulletin discusses the applicability of motor vehicle excise tax to automobiles, buses, trucks, truck tractors, motorcycles, and special mobile equipment. Mobile homes, camper trailers, and aircraft are also subject to excise tax, but are not covered by this bulletin. Detailed information about the excise tax as applied to mobile homes and camper trailers may be found in Property Tax Bulletin No. 6 – Taxation of Mobile Homes and Camper Trailers. For information about the excise tax as applied to aircraft, contact the Property Tax Division using the contact information at the end of this bulletin. As a rule, a registered motor vehicle owned by a person on April 1 and on which an excise tax was paid is exempt from property taxes. A motor vehicle, for which an excise tax has not been paid before property taxes are committed is subject to property tax. The Secretary of State provides municipal excise tax collectors with standard vehicle registration forms for the collection of excise tax. 2. The Motor Vehicle Excise Tax A. When applicable. The excise tax on motor vehicles applies where the owner of the motor vehicle intends to use it on public roads during the year. B. Where excise tax is payable. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

1 Virtues Unfulfilled: the Effects of Land Value

VIRTUES UNFULFILLED: THE EFFECTS OF LAND VALUE TAXATION IN THREE PENNSYLVANIAN CITIES By ROBERT J. MURPHY, JR. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Robert J. Murphy, Jr. 2 To Mom, Dad, family, and friends for their support and encouragement 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my chair, Dr. Andres Blanco, for his guidance, feedback and patience without which the accomplishment of this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. Dawn Jourdan and Dr. David Ling, for carefully prodding aspects of this thesis to help improve its overall quality and validity. I‟d also like to thank friends and cohorts, such as Katie White, Charlie Gibbons, Eric Hilliker, and my parents - Bob and Barb Murphy - among others, who have offered their opinions and guidance on this research when asked. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................... 9 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 10 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... 11 ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. -

Revenue Hearing February 27, 2020

Transcript Prepared by Clerk of the Legislature Transcribers Office Revenue Committee February 27, 2020 LINEHAN: [RECORDER MALFUNCTION] to the Revenue Committee public hearing. My name is Lou Ann Linehan, I'm from Elkhorn, Nebraska, and represent the 39th Legislative District. I serve as the chair of this committee. The committee will take up bills in the order posted. Our hearing today is your part of the public legislative process. This is your opportunity to express your position on the proposed legislation before us today. If you are unable to attend the public hearing and you would, you would like your position stated for the record, you must submit your written testimony by 5:00 p.m. the day prior to the hearing. Letters received after the cutoff will not be read into the record. No exceptions. To better facilitate today's proceedings, I ask that you abide by the following procedures. Please turn off your cell phones or other electronic devices. Move to the chairs in front of the room when you're ready to testify. The order of the testimony is introducer, proponents, opponents, neutral, and closing remarks. If you will be testifying, please complete the green form and hand it to the committee clerk when you come off to testify. If you have written materials that you would like to distribute to the committee, please hand them to the page to distribute, which I will introduce in a moment. We need 11 copies for all committee members and staff. If you need additional copies, please ask the page to make copies for you now. -

SLIP OPINION (Not the Court’S Final Written Decision)

NOTICE: SLIP OPINION (not the court’s final written decision) The opinion that begins on the next page is a slip opinion. Slip opinions are the written opinions that are originally filed by the court. A slip opinion is not necessarily the court’s final written decision. Slip opinions can be changed by subsequent court orders. For example, a court may issue an order making substantive changes to a slip opinion or publishing for precedential purposes a previously “unpublished” opinion. Additionally, nonsubstantive edits (for style, grammar, citation, format, punctuation, etc.) are made before the opinions that have precedential value are published in the official reports of court decisions: the Washington Reports 2d and the Washington Appellate Reports. An opinion in the official reports replaces the slip opinion as the official opinion of the court. The slip opinion that begins on the next page is for a published opinion, and it has since been revised for publication in the printed official reports. The official text of the court’s opinion is found in the advance sheets and the bound volumes of the official reports. Also, an electronic version (intended to mirror the language found in the official reports) of the revised opinion can be found, free of charge, at this website: https://www.lexisnexis.com/clients/wareports. For more information about precedential (published) opinions, nonprecedential (unpublished) opinions, slip opinions, and the official reports, see https://www.courts.wa.gov/opinions and the information that is linked there. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON Certification from the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Washington in NO. -

Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook

Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook 2017 Edition kpmg.ca COMMON FORMS OF REAL OWNERSHIP AND NON-RESIDENTS INVESTING IN GOODS AND SERVICES TAX/ U.S. VACATION PROPERTY APPENDICES ESTATE OWNERSHIP OPERATING ISSUES CANADIAN REAL ESTATE HARMONIZED SALES TAX Welcome Welcome to the 2017 edition of KPMG’s Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook. This book is intended for tax, accounting and finance professionals and others with an interest in the Canadian income tax and GST/HST issues impacting the Canadian real estate industry. KPMG has prepared this tax handbook in order to provide the Canadian real estate industry participants including private and public owners, operators and developers and other advisors with a useful tax technical guide to help them navigate through some of the tax fundamentals that will assist in creating long term value. The world is constantly evolving, and in today’s globally integrated economies, governments continue to introduce tax policy changes and tax authorities continue to invest in advanced technologies and resources for enhanced enforcement. Through KPMG’s assessment of the Canadian Real Estate industry, a number of trends influence today’s tax environment, including: 1. Increasing complexity of relevant laws; 2. Increasing globalization of investment; 3. Increasing sophistication of financial and structural arrangements; 4. Increasing urbanization and intensification; 5. Changing demographics and increasing social media; and, 6. Increasing velocity to take action. With this pace of change, there are new pressures on tax professionals to continue making informed decisions on the company’s day-to-day operations, managing their tax risks and identifying tax efficient planning opportunities. We hope that KPMG’s Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook assists our audience in making more informed decisions on day-to-day operations, and to channel such decisions proactively and positively to create real value for the developers, owners, operators, shareholders, unit holders, investors and lenders who form the real estate industry. -

Property Tax Exemptions for Religious Organizations Church Exemption, Religious Exemption, and Religious Aspect of the Welfare Exemption

Property Tax Exemptions for Religious Organizations Church Exemption, Religious Exemption, and Religious Aspect of the Welfare Exemption PUBLICATION 48 • LDA | SEPTEMBER 2018 BOARD MEMBERS (Names updated October 2019) TED GAINES MALIA M. COHEN ANTONIO VAZQUEZ MIKE SCHAEFER BETTY T. YEE BRENDA FLEMING First District Second District Third District Fourth District State Controller Executive Director Sacramento San Francisco Santa Monica San Diego CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Terms used in this publication . 3 Church Exemption . 4 Religious Exemption . 6 Welfare Exemption (religious aspect) . 8 Property that does not qualify for any exemption . 12 Filing deadlines . 13 For more information . 14 Exhibits A . Index to Church Exemption Laws . 16 B . Index to Religious Exemption Laws . 17 C . Listing of Forms, Church, and Religious Exemptions . 18 D . Index to Welfare Exemption Laws . .19 E . Listing of Forms, Welfare Exemption . 20 SEPTEMBER 2018 | PROPERTY TAX EXEMPTIONS i INTRODUCTION This publication is a guide for organizations that wish to file for and receive a property tax exemption on qualifying church property . It provides basic, general information on the California property tax laws that apply to the exemption of property used for religious purposes . We use the word “church” in this publication as a generic term because the exemption for property used exclusively for religious worship is called the “Church Exemption” (see first bullet, below) . The word is not meant to refer to any particular religious faith . California property tax laws provide for three exemptions that may be claimed on church property: • The Church Exemption, for property that is owned, leased, or rented by a religious organization and used exclusively for religious worship services .