Property Taxes in Canada: Current Issues and Future Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

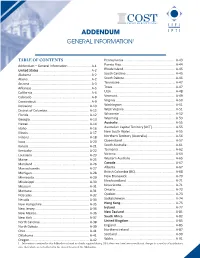

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Cross-Border Group-Taxation and Loss-Offset in the EU - an Analysis for CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) and ETAS (European Tax Allocation System)

arqus Arbeitskreis Quantitative Steuerlehre www.arqus.info Diskussionsbeitrag Nr. 66 Claudia Dahle Michaela Bäumer Cross-Border Group-Taxation and Loss-Offset in the EU - An Analysis for CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) and ETAS (European Tax Allocation System) - April 2009 arqus Diskussionsbeiträge zur Quantitativen Steuerlehre arqus Discussion Papers in Quantitative Tax Research ISSN 1861-8944 Cross-Border Group-Taxation and Loss-Offset in the EU - An Analysis for CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) and ETAS (European Tax Allocation System) - Abstract The European Commission proposed to replace the currently existing Separate Accounting by an EU-wide tax system based on a Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB). Besides the CCCTB, there is an alternative tax reform proposal, the European Tax Allocation System (ETAS). In a dynamic capital budgeting model we analyze the impacts of selected loss-offset limitations currently existing in the EU under both concepts on corporate cross- border real investments of MNE. The analyses show that replacing Separate Accounting by either concept can lead to increasing profitability due to cross-border loss compensation. However, if the profitability increases, the study indicates that the main criteria of decisions on location are the tax rate divergences within the EU Member States. High tax rate differentials in the Member States imply significant redistribution of tax payments under CCCTB and ETAS. The results clarify that in both reform proposals tax payment reallocations occur in favor of the holding. National loss-offset limitations and minimum taxation concepts in tendency lose their impact on the profitability under both proposals. However, we found scenarios in which national minimum taxation can encroach upon the group level, although in our model the minimum taxation’s impacts seem to be slight. -

Bulletin No. 13 (Motor Vehicle Excise Tax & Personal Property Tax)

MAINE REVENUE SERVICES PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NO. 13 MOTOR VEHICLE EXCISE TAX & PERSONAL PROPERTY TAX REFERENCE: 36 M.R.S. §§ 1481 through 1491 December 9, 2019; replaces November 21, 2017 revision 1. General The motor vehicle excise tax is an annual tax imposed for the privilege of operating a motor vehicle on public roads. This bulletin discusses the applicability of motor vehicle excise tax to automobiles, buses, trucks, truck tractors, motorcycles, and special mobile equipment. Mobile homes, camper trailers, and aircraft are also subject to excise tax, but are not covered by this bulletin. Detailed information about the excise tax as applied to mobile homes and camper trailers may be found in Property Tax Bulletin No. 6 – Taxation of Mobile Homes and Camper Trailers. For information about the excise tax as applied to aircraft, contact the Property Tax Division using the contact information at the end of this bulletin. As a rule, a registered motor vehicle owned by a person on April 1 and on which an excise tax was paid is exempt from property taxes. A motor vehicle, for which an excise tax has not been paid before property taxes are committed is subject to property tax. The Secretary of State provides municipal excise tax collectors with standard vehicle registration forms for the collection of excise tax. 2. The Motor Vehicle Excise Tax A. When applicable. The excise tax on motor vehicles applies where the owner of the motor vehicle intends to use it on public roads during the year. B. Where excise tax is payable. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

Canada's Rising Personal Tax Rates and Falling Tax Competitiveness

2020 Canada’s Rising Personal Tax Rates and Falling Tax Competitiveness, 2020 Tegan Hill, Nathaniel Li, and Milagros Palacios fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i Introduction / 1 1. Changes to Canada’s Statutory Marginal Income Tax Rates on Labour Income / 3 2. Statutory Marginal Income Tax Rates in Canada Compared to the United States / 17 3. Statutory Marginal Income Tax Rates in Canada Compared to OECD countries / 27 4. Tax Rate Increases Do Not Generate the Expected Government Revenue / 31 Conclusion / 34 References / 35 Acknowledgments / 42 About the authors / 41 Publishing information / 43 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 44 Purpose, funding, and independence / 44 About the Fraser Institute / 45 Editorial Advisory Board / 46 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Executive Summary In December 2015, Canada’s new Liberal government introduced changes to Canada’s personal income tax system. Among the changes for the 2016 tax year, the federal government added a new income tax bracket, rais- ing the top tax rate from 29 to 33 percent on incomes over $200,000. This increase in the federal tax rate is layered on top of numerous recent prov- incial increases. Starting with Nova Scotia in 2010, through 2019 at least one Canadian government has increased the top personal income tax rate in every year except 2011 and 2019. Over this period, seven out of 10 provincial governments increased tax rates on upper-income earners. As a result, the combined federal and provincial top personal income tax rate has increased in every province since 2009. The largest tax hike has been in Alberta, where the combined top rate increased by 9 percentage points (or 23.1 percent), in part because the new rates were added to a relatively low initial rate. -

1 Virtues Unfulfilled: the Effects of Land Value

VIRTUES UNFULFILLED: THE EFFECTS OF LAND VALUE TAXATION IN THREE PENNSYLVANIAN CITIES By ROBERT J. MURPHY, JR. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Robert J. Murphy, Jr. 2 To Mom, Dad, family, and friends for their support and encouragement 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my chair, Dr. Andres Blanco, for his guidance, feedback and patience without which the accomplishment of this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. Dawn Jourdan and Dr. David Ling, for carefully prodding aspects of this thesis to help improve its overall quality and validity. I‟d also like to thank friends and cohorts, such as Katie White, Charlie Gibbons, Eric Hilliker, and my parents - Bob and Barb Murphy - among others, who have offered their opinions and guidance on this research when asked. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................... 9 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 10 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... 11 ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. -

Carbon Taxation in Canada: Impact of Revenue Recycling Kathryn Harrison University of British Columbia Context

Carbon Taxation in Canada: Impact of Revenue Recycling Kathryn Harrison University of British Columbia Context • Highly carbon-intensive economy • 19 tonnes CO2eq/person/yr • Growing emissions from fossil fuels exports • Decentralized federation • Provinces own the fossil fuels Provincial Per Capita GHG Emissions, t/yr 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 NL PE NS NB QC ON MB SK AB BC British Columbia’s Carbon Tax • All combustion emissions, except flights • $10/tonne (2008) to $30/tonne (2012) • Frozen 2012-2018, now $40/tonne • Initially revenue-neutral • Reduction in business and individual income tax rates • Low income tax credit • >$30/tonne hypothecated British Columbia: Did Tax Cuts build support? • Business: Yes • Revenue-neutral was condition of acceptance • Voters: No • Opposition emerged in rural communities • “Axe the tax” campaign by legislative opposition • Popularity plummeted • Tax cuts didn’t overcome: • Low visibility • Doesn’t feel like a gift if still paying taxes • Government reelected despite carbon tax • Support rebounded after 3 yrs Alberta Carbon Tax • 2007 intensity-based carbon price for industry • 2017 carbon tax extended to households: • $30/tonne in 2018 • Concern for climate, but also for industry reputation • Revenues • Low income dividends • Green spending • General revenues Alberta Carbon Tax • Defeat of government 2019 • Unpopular tax • Reunited right • Bill 1: Repeal of “Job-Killing Carbon Tax” • Revenue return probably small impact Pan-Canadian Carbon Pricing • 2016: Provincial choice (ETS or tax), federal backstop -

Ownership/Transfer of Canadian Property

OWNERSHIP/TRANSFER OF CANADIAN PROPERTY New York State Bar Association, Trust and Estates Law Section Fall Meeting – October 29-30, 2015 Presented By: Richard Stephen Halinda Richard S. Halinda Law Professional Corporation 1222 Garrison Road, Fort Erie, Ontario (P) 905-871-4556 (F) 905-871-5215 (Email) [email protected] Page 1 Taxation in Canada has a number of sources : 1. Employment Income 2. Interest or Royalty Income 3. Rental Income 4. Capital Gains from the sale or deemed sale of Canadian Taxable Property I. Taxable Canadian Property Dispositions: 1. Third Party Sale (actual sale) 2. Non-Arm’s Length Transfer (deemed sale): -gift -divorce/separation -to/from a corporation -to/from a trust 3. On Death (deemed sale) II. The Seller/Transferor/Deceased: Capital Gains Tax Consequences: 1. For a Third Party Sale of Capital Property: CAPITAL GAIN = Sale Proceeds - Adjusted Cost Base* 2/3. For Non-Arms-Length Transactions OR in the case of Death (deemed dispositions): CAPITAL GAIN= Fair Market Value at time of Disposition - Adjusted Cost Base* * Note: in the case of Adjusted Cost Base there may be options depending on when the property was acquired by the Seller/Transferor/Deceased: For all acquisitions after September 26, 1980 : ADJUSTED COST BASE = Original Purchase Price + Closing Costs at time of Purchase + Verifiable Capital Improvements Page 2 For acquisition prior to September 26, 1980 the US-Canada Tax Treaty provides some relief from the capital gains that would otherwise be applicable and allows the Seller/Transferor/Deceased to increase its “Adjusted Cost Base”, in one of two ways: ADJUSTED COST BASE = December 31, 1984 Fair Market Value of Property + Verifiable Capital Improvements incurred after Dec. -

Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook

Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook 2017 Edition kpmg.ca COMMON FORMS OF REAL OWNERSHIP AND NON-RESIDENTS INVESTING IN GOODS AND SERVICES TAX/ U.S. VACATION PROPERTY APPENDICES ESTATE OWNERSHIP OPERATING ISSUES CANADIAN REAL ESTATE HARMONIZED SALES TAX Welcome Welcome to the 2017 edition of KPMG’s Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook. This book is intended for tax, accounting and finance professionals and others with an interest in the Canadian income tax and GST/HST issues impacting the Canadian real estate industry. KPMG has prepared this tax handbook in order to provide the Canadian real estate industry participants including private and public owners, operators and developers and other advisors with a useful tax technical guide to help them navigate through some of the tax fundamentals that will assist in creating long term value. The world is constantly evolving, and in today’s globally integrated economies, governments continue to introduce tax policy changes and tax authorities continue to invest in advanced technologies and resources for enhanced enforcement. Through KPMG’s assessment of the Canadian Real Estate industry, a number of trends influence today’s tax environment, including: 1. Increasing complexity of relevant laws; 2. Increasing globalization of investment; 3. Increasing sophistication of financial and structural arrangements; 4. Increasing urbanization and intensification; 5. Changing demographics and increasing social media; and, 6. Increasing velocity to take action. With this pace of change, there are new pressures on tax professionals to continue making informed decisions on the company’s day-to-day operations, managing their tax risks and identifying tax efficient planning opportunities. We hope that KPMG’s Canadian Real Estate Tax Handbook assists our audience in making more informed decisions on day-to-day operations, and to channel such decisions proactively and positively to create real value for the developers, owners, operators, shareholders, unit holders, investors and lenders who form the real estate industry. -

Property Tax Exemptions for Religious Organizations Church Exemption, Religious Exemption, and Religious Aspect of the Welfare Exemption

Property Tax Exemptions for Religious Organizations Church Exemption, Religious Exemption, and Religious Aspect of the Welfare Exemption PUBLICATION 48 • LDA | SEPTEMBER 2018 BOARD MEMBERS (Names updated October 2019) TED GAINES MALIA M. COHEN ANTONIO VAZQUEZ MIKE SCHAEFER BETTY T. YEE BRENDA FLEMING First District Second District Third District Fourth District State Controller Executive Director Sacramento San Francisco Santa Monica San Diego CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Terms used in this publication . 3 Church Exemption . 4 Religious Exemption . 6 Welfare Exemption (religious aspect) . 8 Property that does not qualify for any exemption . 12 Filing deadlines . 13 For more information . 14 Exhibits A . Index to Church Exemption Laws . 16 B . Index to Religious Exemption Laws . 17 C . Listing of Forms, Church, and Religious Exemptions . 18 D . Index to Welfare Exemption Laws . .19 E . Listing of Forms, Welfare Exemption . 20 SEPTEMBER 2018 | PROPERTY TAX EXEMPTIONS i INTRODUCTION This publication is a guide for organizations that wish to file for and receive a property tax exemption on qualifying church property . It provides basic, general information on the California property tax laws that apply to the exemption of property used for religious purposes . We use the word “church” in this publication as a generic term because the exemption for property used exclusively for religious worship is called the “Church Exemption” (see first bullet, below) . The word is not meant to refer to any particular religious faith . California property tax laws provide for three exemptions that may be claimed on church property: • The Church Exemption, for property that is owned, leased, or rented by a religious organization and used exclusively for religious worship services . -

Taxes in Canada’S Largest Metropolitan Areas?

Josef Filipowicz and Steven Globerman Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada’s Largest Metropolitan Areas? 2019 • Fraser Institute Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada’s Largest Metropolitan Areas? by Josef Filipowicz and Steven Globerman fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i 1. Introduction / 1 2. What Are Property Taxes? / 3 3. The Causes and Consequences of Higher Tax Rates on Commercial and Industrial Properties / 4 4. Property Tax Rates and Ratios in Canada’s Five Largest Metropolitan Areas / 8 5. Conclusion / 18 Appendix Property Tax Rates by Metropolitan Region / 19 About the authors / 26 Acknowledgments / 26 About the Fraser Institute / 27 Publishing Information / 28 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 29 Purpose, Funding, and Independence / 29 Editorial Advisory Board / 30 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Filipowicz and Globerman • Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada? • i Executive Summary Property taxes are the primary source of revenue for local governments in Canada. The revenues raised are used to pay for a variety of public services including police, schools, fire protection, roads, and sewers. Owners of different classes of property, including residential, commercial and industrial, pay taxes. In principle, both considerations of efficiency and fairness suggest that the taxes paid by individual property owners should reflect the costs that they impose on municipal service providers. This is commonly referred to as the “user pay” principle. Therefore, to the extent that property tax rates differ across property classes, the differences should reflect commensurate differences in the relative costs that those asset classes impose on municipalities. This study compares property tax ratios for major residential and non-residential property classes in five of Canada’s largest metropolitan areas: Ontario’s Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, Quebec’s Greater Montreal, British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, and Alberta’s Calgary and Edmonton regions.