'Greening' the Tax System Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries Creating Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries 2014 About the OECD The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Union takes part in the work of the OECD. Since the 1990s, the OECD Task Force for the Implementation of the Environmental Action Programme (the EAP Task Force) has been supporting countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia to reconcile their environment and economic goals. About the EaP GREEN programme The “Greening Economies in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood” (EaP GREEN) programme aims to support the six Eastern Partnership countries to move towards green economy by decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and resource depletion. The six EaP countries are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. -

County Tax Settlement Guide

SUGGESTED PROCEDURES FOR THE PREPARATION OF THE COUNTY FINAL TAX SETTLEMENT June 1, 2019 SUGGESTED PROCEDURES FOR THE PREPARATION OF THE COUNTY FINAL TAX SETTLEMENT INDEX Tax Settlement Narrative Real Estate Page 1 – 4 Personal Page 5 – 6 Utility and Carrier Page 7 Net Tax and Distribution of Net Tax Page 7 – 11 Excess Collector’s Commission Page 12 Tax Settlement Checklist Page 13 Sample Tax Settlement Exhibits Page 14 – 22 Rate Calculation Examples Page 23 – 25 Cost Sheet Example Page 26 Monthly Distribution of Ad Valorem Taxes Page 27 Monthly Distribution of Sales Tax Rebate Page 28 Sales Tax Final Tax Settlement Page 29 – 30 General Information Pertaining to Ad Valorem Taxation Page 31 – 55 Certain Legislative Acts Pertaining to Taxes Page 56 – 66 GENERAL NARRATIVE The millage rates used for the extension of taxes will be those millage rates levied by the Quorum Court in its regular meeting in November of each year, in accordance with Ark. Code Ann. § 14- 14-904. The 2001 Legislature amended Ark. Code Ann. § 14-14-904, allowing the Quorum Court to correct millage levies in cases where an incorrect levy was due to clerical errors and/or the failure of the taxing entity to report the correct millage. The correction is effected by a county court order. In this manual, the millage rates have equalized for all taxing units and, therefore, are the same for both real estate and personal property. The breakdown of this sample tax settlement into real, personal, and utility taxes has a dual purpose: (1) to provide a mechanism to identify and isolate possible errors by type of tax and (2) to recognize those counties where the real and personal tax rates have not yet equalized. -

Tax Strategies for Selling Your Company by David Boatwright and Agnes Gesiko Latham & Watkins LLP

Tax Strategies For Selling Your Company By David Boatwright and Agnes Gesiko Latham & Watkins LLP The tax consequences of an asset sale by an entity can be very different than the consequences of a sale of the outstanding equity interests in the entity, and the use of buyer equity interests as acquisition currency may produce very different tax consequences than the use of cash or other property. This article explores certain of those differences and sets forth related strategies for maximizing the seller’s after-tax cash flow from a sale transaction. Taxes on the Sale of a Business The tax law presumes that gain or loss results upon the sale or exchange of property. This gain or loss must be reported on a tax return, unless a specific exception set forth in the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”) or the Treasury Department’s income tax regulations provide otherwise. When a transaction is taxable under applicable principles of income tax law, the seller’s taxable gain is determined by the following formula: the “amount realized” over the “adjusted tax basis” of the assets sold equals “taxable gain.” If the adjusted tax basis exceeds the amount realized, the seller has a “tax loss.” The amount realized is the amount paid by the buyer, including any debt assumed by the buyer. The adjusted tax basis of each asset sold is generally the amount originally paid for the asset, plus amounts expended to improve the asset (which were not deducted when paid), less depreciation or amortization deductions (if any) previously allowable with respect to the asset. -

City of San Marcos Sales Tax Update Q22018 Third Quarter Receipts for Second Quarter Sales (April - June 2018)

City of San Marcos Sales Tax Update Q22018 Third Quarter Receipts for Second Quarter Sales (April - June 2018) San Marcos SALES TAX BY MAJOR BUSINESS GROUP In Brief $1,400,000 2nd Quarter 2017 $1,200,000 San Marcos’ receipts from April 2nd Quarter 2018 through June were 3.9% below the $1,000,000 second sales period in 2017 though the decline was the result of the State’s transition to a new software $800,000 and reporting system that caused a delay in processing thousands of $600,000 payments statewide. Sizeable local allocations remain outstanding, par- $400,000 ticularly for home furnishings, build- ing materials, service stations and $200,000 casual dining restaurants. Partial- ly offsetting these impacts, the City received an extra department store $0 catch-up payment that had been General Building County Restaurants Business Autos Fuel and Food delayed from last quarter due to the Consumer and and State and and and Service and Goods Construction Pools Hotels Industry Transportation Stations Drugs same software conversion issue. Excluding reporting aberrations, ac- tual sales were up 3.0%. Progress was led by higher re- TOP 25 PRODUCERS ceipts at local service stations. The IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER REVENUE COMPARISON price of gas has been driven high- ABC Supply Co Hughes Water & Four Quarters – Fiscal Year To Date (Q3 to Q2) Sewer er over the past year by simmering Albertsons Hunter Industries global political tension and robust Ashley Furniture 2016-17 2017-18 economic growth that has lifted de- Homestore Jeromes Furniture mand. Best Buy Kohls Point-of-Sale $14,377,888 $14,692,328 The City also received a 12% larg- Biggs Harley KRC Rock Davidson County Pool er allocation from the countywide Landsberg Orora 2,217,780 2,261,825 use tax pool. -

Improving the Tax System in Indonesia

OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 998 Improving the Tax System Jens Matthias Arnold in Indonesia https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k912j3r2qmr-en Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 30-Oct-2012 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 IMPROVING THE TAX SYSTEM IN INDONESIA ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPERS No. 998 By Jens Arnold All OECD Economics Department Working Papers are available through OECD's Internet website at http://www.oecd.org/eco/Workingpapers English - Or. English JT03329829 Complete document available on OLIS in its original format This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. ECO/WKP(2012)75 ABSTRACT/RESUME Improving the tax system in Indonesia Indonesia has come a long way in improving its tax system over the last decade, both in terms of revenues raised and administrative efficiency. Nonetheless, the tax take is still low, given the need for more spending on infrastructure and social protection. With the exception of the natural resources sector, increasing tax revenues would be best achieved through broadening tax bases and improving tax administration, rather than changes in the tax schedule that seems broadly in line with international practice. Possible measures to broaden the tax base include bringing more of the self-employed into the tax system, subjecting employer-provided fringe benefits and allowances to personal income taxation and reducing the exemptions from value-added taxes. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

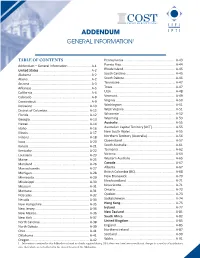

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

Westvirginia

W E S T V I R G I N I A DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE Joint Select Committee on Tax Reform Current Tax Structure DEPUTY REVENUE SECRETARY MARK B. MUCHOW West Virginia State Capitol May 4, 2015 Secretary Robert S. Kiss Governor Earl Ray Tomblin Some Notes Concerning Taxation • Tax = price paid for government goods and services – Higher price = less demand (budget surplus) – Lower price = more demand • Federal deficit spending • Exporting of tax (e.g., Destination gaming, tourism, certain taxes) • All taxes are paid by individuals – economic incidence • Two principles of taxation – Ability to Pay (Federal Government) – Benefits (State and Local Governments) • Three broad categories of taxation – Property (Real estate taxes, ad valorem tax, franchise tax) – Consumption (General sales, gross receipt, excise) – Income (personal income, profits, wages, dividends) State and Local Government Expenditures 2011: WV Ranks 14th in Per Pupil K-12 Education Funding; 16th in Per Capita Higher Education Funding; 11th in Per Capita Highways Funding; 48th in Per Capita Police Protection Sources: U.S. Census Bureau & State Higher Education Executive Officers Association Historical Events Shape Tax System • Prohibition: (WV goes Dry in 1914: New Tax System ) – Move to State consumption taxes (B&O and gasoline) • Great Depression of the 1930s – Property Tax Revolt (Move toward government centralization) – Move to more State consumption taxation (Sales Tax and more) – Roads transferred from counties to State • Educating Baby Boomers in 1960s: – Higher sales tax rates -

Financial Transaction Taxes

FINANCIAL MM TRANSACTION TAXES: A tax on investors, taxpayers, and consumers Center for Capital Markets Competitiveness 1 FINANCIAL TRANSACTION TAXES: A tax on investors, taxpayers, and consumers James J. Angel, Ph.D., CFA Associate Professor of Finance Georgetown University [email protected] McDonough School of Business Hariri Building Washington, DC 20057 202-687-3765 Twitter: @GUFinProf The author gratefully acknowledges financial support for this project from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chamber or Georgetown University. 2 Financial Transaction Taxes: A tax on investors, taxpayers, and consumers FINANCIAL TRANSACTIN TAES: Table of Contents A tax on investors, taxpayers, and Executive Summary .........................................................................................4 consumers Introduction .....................................................................................................6 The direct tax burden .......................................................................................7 The indirect tax burden ....................................................................................8 The derivatives market and risk management .............................................. 14 Economic impact of an FTT ............................................................................17 The U.S. experience ..................................................................................... 23 International experience -

Country Update: Australia

www.pwc.com Country update: Australia Anthony Klein Partner, PwC Australia Liam Collins Partner, PwC Singapore Agenda 1. Economic and social challenges 2. Tax and politics 3. Recent developments 4. 2015 Federal Budget – key announcements 5. Regulatory environment – changes at the ATO 6. Q&A Global Tax Symposium – Asia 2015 PwC 2 Economic and social challenges Global Tax Symposium – Asia 2015 PwC 3 $ billion 10,000 12,000 14,000 ‐ 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 2,000 PwC Tax – Symposium Global 2015 Asia Economic outlook 0 Australia’s net debt levels, A$ billion net debt levels, Australia’s 2002‐03 2003‐04 2004‐05 2005‐06 2006‐07 2007‐08 2008‐09 2009‐10 2010‐11 2011‐12 2012‐13 2013‐14 2014‐15 2015‐16 Commonwealth 2016‐17 2017‐18 2018‐19 2019‐20 Current year 2020‐21 2021‐22 2022‐23 States 2023‐24 2024‐25 and 2025‐26 territories 2026‐27 2027‐28 2028‐29 2029‐30 2030‐31 Federation 2031‐32 2032‐33 2033‐34 2034‐35 2035‐36 2036‐37 2037‐38 2038‐39 2039‐40 2040‐41 2041‐42 2042‐43 2043‐44 2044‐45 2045‐46 2046‐47 2047‐48 2048‐49 2049‐50 4 Impact of iron ore prices and AUD 1980 to 2015 200.00 1.5000 180.00 1.3000 160.00 140.00 1.1000 120.00 0.9000 Iron Ore Price 100.00 AUD:USD 0.7000 80.00 60.00 0.5000 40.00 0.3000 20.00 0.00 0.1000 Global Tax Symposium – Asia 2015 PwC 5 Domestic challenges Domestic economy • Declining per capita income • Government spending previously underpinned by resources boom – now less affordable • As a consequence, deficits ‘as far as the eye can see’ • A Government short on political capital Demographic challenges • Ageing population -

Taxation of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions

KPMG INTERNATIONAL Taxation of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Jersey kpmg.com 2 | Jersey: Taxation of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Jersey Introduction Recent developments Jersey is a dependency of the British Crown and benefits The EU Code of Conduct on Business Taxation Group from close ties to both the United Kingdom, being in the assessed Jersey’s zero/ten tax system in 2011. The same time zone and having a similar regulatory environment assessment found that the interaction of the zero percent and business culture, and Europe. With its long tradition of rate and the deemed dividend and full attribution provisions to political and economic stability, low-tax regime and economy be harmful. The dividend and attribution provisions sought to dominated by financial institutions, Jersey is an attractive assess Jersey resident individual shareholders on the profits location for investment. of Jersey companies subject to the zero percent rate. As a result of the assessment, legislation was passed to abolish The island has undertaken steps to counter its tax haven the deemed distribution and full attribution taxation provisions image in recent times. It was placed on the Organisation for for profits arising on or after 1 January 2012, thereby removing Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) white list the harmful element of the regime. The EU Code of Conduct in April 2009. In September 2009, the International Monetary on Business Taxation Group accepted Jersey’s position Fund issued a report in which it commented that financial and submitted to the EU’s Economic and Financial Affairs sector regulation and supervision are of a high standard and Council (ECOFIN) that Jersey had rolled back the harmful comply well with international standards.