An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TTB F 5000.24Sm Excise Tax Return

OMB No. 1513-0083 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY 1. SERIAL NUMBER ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO TAX AND TRADE BUREAU (TTB) EXCISE TAX RETURN (Prepare in duplicate – See instructions below) 3. AMOUNT OF PAYMENT 2. FORM OF PAYMENT $ CHECK MONEY ORDER EFT OTHER (Specify) NOTE: PLEASE MAKE CHECKS OR MONEY ORDERS PAYABLE TO THE ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO TAX AND 4. RETURN COVERS (Check one) BEGINNING TRADE BUREAU (SHOW EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ON ALL CHECKS OR MONEY ORDERS). IF PREPAYMENT PERIOD YOU SEND A CHECK, SEE PAPER CHECK CONVERSION ENDING NOTICE BELOW. 5. DATE PRODUCTS TO BE REMOVED (For Prepayment Returns Only) FOR TTB USE ONLY 6. EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER 7. PLANT, REGISTRY, OR PERMIT NUMBER TAX $ PENALTY 8. NAME AND ADDRESS OF TAXPAYER (Include ZIP Code) INTEREST TOTAL $ EXAMINED BY: DATE EXAMINED: CALCULATION OF TAX DUE (Before making entries on lines 18 – 21, complete Schedules A and B) PRODUCT AMOUNT OF TAX (a) (b) 9. DISTILLED SPIRITS 10. WINE 11. BEER 12. CIGARS 13. CIGARETTES 14. CIGARETTE PAPERS AND/OR CIGARETTE TUBES 15. CHEWING TOBACCO AND/OR SNUFF 16. PIPE TOBACCO AND/OR ROLL-YOUR-OWN TOBACCO 17. TOTAL TAX LIABILITY (Total of lines 9-16) $ 18. ADJUSTMENTS INCREASING AMOUNT DUE (From line 29) 19. GROSS AMOUNT DUE (Line 17 plus line 18) $ 20. ADJUSTMENTS DECREASING AMOUNT DUE (From line 34) 21. AMOUNT TO BE PAID WITH THIS RETURN (Line 19 minus line 20) $ Under penalties of perjury, I declare that I have examined this return (including any accompanying explanations, statements, schedules, and forms) and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct, and includes all transactions and tax liabilities required by law or regulations to be reported. -

Tax Policy Update 16 27 April

Policy update Tax Policy Update 16 27 April HIGHLIGHTS • European Parliament: Plenary discusses state of public CBCR negotiations 18 April • Council: member states freeze CCTB negotiations in order to assess its impact on tax bases 20 April • European Commission: new rules for whistleblower protection proposed, covers tax avoidance too 23 April • European Parliament: ECON Committee holds public hearing on definitive VAT system 24 April • European Commission: new Company Law Package with tax dimension published 25 April European Commission Commission kicks off Fair Taxation Roadshow 19 April The European Commission has launched a series of seminars on fair taxation, with a first event held in Riga on 19 April. These seminars bring together civil society, business representatives, policy makers, academics and interested citizens to discuss and exchange views on tax avoidance and tax evasion. Further events are planned throughout 2018 in Austria (17 May), France (8 June), Italy (19 September) and Ireland (9 October). The Commission hopes that the roadshow seminars will further encourage active engagement on tax fairness principles at EU, national and local levels. In particular, a main aim seems to be to spread the tax debate currently ongoing at the EU-level into member states as well. Commission launches VAT MOSS portal 19 April The European Commission has launched a Mini-One Stop Shop (MOSS) portal for VAT purposes. The new MOSS portal provides comprehensive and easily accessible information on VAT rates for telecom, broadcasting and e- services, and explains how the MOSS can be used to declare and pay VAT on such services. 1 Commission proposes EU rules for whistleblower protection, covers tax avoidance as well 23 April The European Commission has published a new Directive for the protection of whistleblowers. -

Improving the Tax System in Indonesia

OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 998 Improving the Tax System Jens Matthias Arnold in Indonesia https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k912j3r2qmr-en Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 30-Oct-2012 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 IMPROVING THE TAX SYSTEM IN INDONESIA ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPERS No. 998 By Jens Arnold All OECD Economics Department Working Papers are available through OECD's Internet website at http://www.oecd.org/eco/Workingpapers English - Or. English JT03329829 Complete document available on OLIS in its original format This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. ECO/WKP(2012)75 ABSTRACT/RESUME Improving the tax system in Indonesia Indonesia has come a long way in improving its tax system over the last decade, both in terms of revenues raised and administrative efficiency. Nonetheless, the tax take is still low, given the need for more spending on infrastructure and social protection. With the exception of the natural resources sector, increasing tax revenues would be best achieved through broadening tax bases and improving tax administration, rather than changes in the tax schedule that seems broadly in line with international practice. Possible measures to broaden the tax base include bringing more of the self-employed into the tax system, subjecting employer-provided fringe benefits and allowances to personal income taxation and reducing the exemptions from value-added taxes. -

Econ 230A: Public Economics Lecture: Tax Incidence 1

Econ 230A: Public Economics Lecture: Tax Incidence 1 Hilary Hoynes UC Davis, Winter 2013 1These lecture notes are partially based on lectures developed by Raj Chetty and Day Manoli. Many thanks to them for their generosity. Hilary Hoynes () Incidence UCDavis,Winter2013 1/61 Outline of Lecture 1 What is tax incidence? 2 Partial Equilibrium Incidence I Theory: Kotliko¤ and Summers, Handbook of Public Finance, Vol 2 I Empirical Applications: Doyle and Samphantharak (2008), Hastings and Washington 3 General Equilibrium Incidence – WILL NOT COVER 4 Capitalization & Asset Market Approach I Empirical Application: Linden and Rocko¤ (2008) 5 Mandated Bene…ts I Theory: Summers (1989) I Empirical Application: Gruber (1994) Hilary Hoynes () Incidence UCDavis,Winter2013 2/61 1. What is tax incidence? Tax incidence is the study of the e¤ects of tax policies on prices and the distribution of utilities/welfare. What happens to market prices when a tax is introduced or changed? Examples: I what happens when impose $1 per pack tax on cigarettes? Introduce an earnings subsidy (EITC)? provide a subsidy for food (food stamps)? I e¤ect on price –> distributional e¤ects on smokers, pro…ts of producers, shareholders, farmers,... This is positive analysis: typically the …rst step in policy evaluation; it is an input to later thinking about what policy maximizes social welfare. Empirical analysis is a big part of this literature because theory is itself largely inconclusive about magnitudes, although informative about signs and comparative statics. Hilary Hoynes () Incidence UCDavis,Winter2013 3/61 1. What is tax incidence? (cont) Tax incidence is not an accounting exercise but an analytical characterization of changes in economic equilibria when taxes are changed. -

GAO-05-1009SP Understanding the Tax Reform Debate: Background, Criteria, and Questions

Contents Preface 1 Introduction 4 Section 1 7 The Current Tax System 7 Revenue— Historical Trends in Tax Revenue 13 Taxes Exist to Historical Trends in Federal Spending 14 Borrowing versus Taxing as a Source of Fund Resources 15 Government Long-term Fiscal Challenge 17 Revenue Effects of Federal Tax Policy Changes 19 General Options Suggested for Fundamental Tax Reform 21 Key Questions 22 Section 2 24 Equity 26 Criteria for a Equity Principles 26 Good Tax Measuring Who Pays: Distributional Analysis 30 System Key Questions 33 Economic Efficiency 35 Taxes and Economic Decision Making 37 Measuring Economic Efficiency 40 Taxing Work and Savings Decisions 41 Realizing Efficiency Gains 43 Key Questions 43 Simplicity, Transparency, and Administrability 45 Simplicity 45 Transparency 47 Administrability 49 GAO-05-1009SP i Contents Trade-offs between Equity, Economic Efficiency, and Simplicity, Transparency, and Administrability 52 Key Questions 52 Section 3 54 Deciding if Transition Relief Is Necessary 54 Transitioning Identifying Affected Parties 55 to a Different Revenue Effects of Transition Relief 56 Policy Tools for Implementing Tax System Transition Rules 56 Key Questions 57 Appendixes Appendix I: Key Questions 58 Section I: Revenue Needs—Taxes Exist to Fund Government 58 Section II: Criteria for a Good Tax System 59 Equity 59 Efficiency 60 Simplicity, Transparency, and Administrability 61 Section III: Transitioning to a Different Tax System 62 Appendix II: Selected Bibliography and Related Reports 63 Government Accountability Office 63 Congressional -

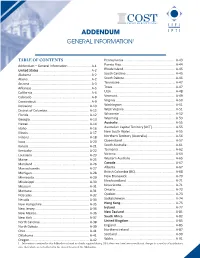

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Canada Taxation of Foreign Passive Income (FAPI)

INTERNATIONAL TAX POLICY FORUM / GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY LAW CENTER Reform of International Tax: Canada, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States January 21, 2011 Gewirz Student Center, 12th floor 120 F Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 International Tax Policy Forum International Tax Policy Forum and Georgetown University Law Center Conference on: REFORM OF INTERNATIONAL TAX: CANADA, JAPAN, UNITED KINGDOM, AND UNITED STATES Table of Contents 1) Agenda ................................................................................................................................................... 1 2) Sponsoring Organizations a) About ITPF ....................................................................................................................................... 2 b) About Georgetown University Law Center ....................................................................................... 3 3) Taxation of International Income in Canada, Japan, UK, and US a) International Tax Rules in Canada, Japan, the UK and US (J. Mintz Presentation) ....................... 4 b) Canada i) S. Richardson, Presentation on Canadian international tax reform (Jan. 2011) ....................... 9 ii) N. Pantaleo, Presentation on Canada's taxation of foreign business income (Jan. 2011) ..... 12 iii) Advisory Panel on Canada’s System of International Taxation, Enhancing Canada’s International Tax Advantage, (Dec. 2008) [Executive Summary] ........................................... 16 c) UK i) M. Williams, Presentation on UK international tax -

Download Article (PDF)

5th International Conference on Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation (ICAAT 2016) TAX TRANSPARENCY – AN ANALYSIS OF THE LUXLEAKS FIRMS Johannes Manthey University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Dirk Kiesewetter University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Abstract This paper finds that the firms involved in the Luxembourg Leaks (‘LuxLeaks’) scandal are less transparent measured by the engagement in earnings management, analyst coverage, analyst accuracy, accounting standards and auditor choice. The analysis is based on the LuxLeaks sample and compared to a control group of large multinational companies. The panel dataset covers the years from 2001 to 2015 and comprises 19,109 observations. The LuxLeaks firms appear to engage in higher levels of discretionary earnings management measured by the variability of net income to cash flows from operations and the correlation between cash flows from operations and accruals. The LuxLeaks sample shows a lower analyst coverage, lower willingness to switch to IFRS and a lower Big4 auditor rate. The difference in difference design supports these findings regarding earnings management and the analyst coverage. The analysis concludes that the LuxLeaks firms are less transparent and infers a relation between corporate transparency and the engagement in tax avoidance. The paper aims to establish the relationship between tax avoidance and transparency in order to give guidance for future policy. The research highlights the complex causes and effects of tax management and supports a cost benefit analysis of future tax regulation. Keywords: Tax Avoidance, Transparency, Earnings Management JEL Classification: H20, H25, H26 1. Introduction The Luxembourg Leaks (’LuxLeaks’) scandal made public some of the tax strategies used by multinational companies. -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

An Analysis of a Consumption Tax for California

An Analysis of a Consumption Tax for California 1 Fred E. Foldvary, Colleen E. Haight, and Annette Nellen The authors conducted this study at the request of the California Senate Office of Research (SOR). This report presents the authors’ opinions and findings, which are not necessarily endorsed by the SOR. 1 Dr. Fred E. Foldvary, Lecturer, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Colleen E. Haight, Associate Professor and Chair, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Annette Nellen, Professor, Lucas College of Business, San Jose State University, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank the Center for California Studies at California State University, Sacramento for their [email protected]; Dr. Colleen E. Haight, Associate Professor and Chair, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Annette Nellen, Professor, Lucas College of Business, San Jose State University, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank the Center for California Studies at California State University, Sacramento for their funding. Executive Summary This study attempts to answer the question: should California broaden its use of a consumption tax, and if so, how? In considering this question, we must also consider the ultimate purpose of a system of taxation: namely to raise sufficient revenues to support the spending goals of the state in the most efficient manner. Recent tax reform proposals in California have included a business net receipts tax (BNRT), as well as a more comprehensive sales tax. However, though the timing is right, given the increasingly global and digital nature of California’s economy, the recent 2008 recession tabled the discussion in favor of more urgent matters. -

Horizontal Equity Effects in Energy Regulation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HORIZONTAL EQUITY EFFECTS IN ENERGY REGULATION Carolyn Fischer William A. Pizer Working Paper 24033 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24033 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2017, Revised July 2018 Previously circulated as "Equity Effects in Energy Regulation." Carolyn Fischer is Senior Fellow at Resources for the Future ([email protected]); Professor at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; Marks Visiting Professor at Gothenburg University; Visiting Senior Researcher at Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei; and CESifo Research Network Fellow. William A. Pizer is Susan B. King Professor of Public Policy, Sanford School, and Faculty Fellow, Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University ([email protected]); University Fellow, Resources for the Future; Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research. Fischer is grateful for the support of the European Community’s Marie Sk odowska–Curie International Incoming Fellowship, “STRATECHPOL – Strategic Clean Technology Policies for Climate Change,” financed under the EC Grant Agreement PIIF-GA-2013-623783. This work was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Grant G-2016-20166028. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Carolyn Fischer and William A. Pizer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain by Benjamin Zenas Cannon Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Prof

Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain By Benjamin Zenas Cannon A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Kent Puckett Professor Andrew Shanken Spring 2014 Disappearing Walls: Literature and Architecture in Victorian Britain © 2014 By Benjamin Zenas Cannon Abstract Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain By Benjamin Zenas Cannon Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Prof. Ian Duncan, Chair From Discipline and Punish and The Madwoman in the Attic to recent work on urbanism, display, and material culture, criticism has regularly cast nineteenth-century architecture not as a set of buildings but as an ideological metastructure. Seen primarily in terms of prisons, museums, and the newly gendered private home, this “grid of intelligibility” polices the boundaries not only of physical interaction but also of cultural values and modes of knowing. As my project argues, however, architecture in fact offered nineteenth-century theorists unique opportunities to broaden radically the parameters of aesthetic agency. A building is generally not built by a single person; it is almost always a corporate effort. At the same time, a building will often exist for long enough that it will decay or be repurposed. Long before literature asked “what is an author?” Victorian architecture theory asked: “who can be said to have made this?” Figures like John Ruskin, Owen Jones, and James Fergusson radicalize this question into what I call a redistribution of intention, an ethically charged recognition of the value of other makers.