The Evolution of the Vermont State Tax System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

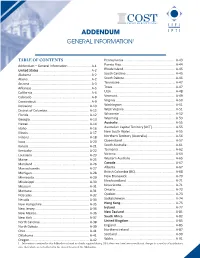

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Mass Taxation and State-Society Relations in East Africa

Chapter 5. Mass taxation and state-society relations in East Africa Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Ole Therkildsen* Chapter 5 (pp. 114 – 134) in Deborah Braütigam, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad & Mick Moore eds. (2008). Taxation and state building in developing countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.cambridge.org/no/academic/subjects/politics-international-relations/comparative- politics/taxation-and-state-building-developing-countries-capacity-and-consent?format=HB Introduction In East Africa, as in many other agrarian societies in the recent past, most people experience direct taxation mainly in the form of poll taxes levied by local governments. Poll taxes vary in detail, but characteristically are levied on every adult male at the same rate, with little or no adjustment for differences in individual incomes or circumstances. In East Africa and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, poll taxes have been the dominant source of revenue for local governments, although their financial importance has tended to diminish over time. They have their origins in the colonial era, where at first they were effectively an alternative to forced labour. Poll taxes have been a source of tension and conflict between state authorities and rural people from the colonial period until today, and a catalyst for many rural rebellions. This chapter has two main purposes. The first, pursued through a history of poll taxes in Tanzania and Uganda, is to explain how they have affected state-society relations and why it has taken so long to abolish them. The broad point here is that, insofar as poll taxes have contributed to democratisation, this is not through revenue bargaining, in which the state provides representation for taxpayers in exchange for tax revenues (Levi 1988; Tilly 1990; Moore 1998; and Moore in this volume). -

What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax? Wendy G

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship Spring 2014 What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax? Wendy G. Gerzog University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, Taxation-Federal Commons, Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift ommonC s, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax?, 49 Real Prop. Tr. & Est. L.J. 163 (2014-2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT'S WRONG WITH A FEDERAL INHERITANCE TAX? Wendy C. Gerzog* Synopsis: Scholars have proposed a federal inheritance tax as an alternative to the current federal transfer taxes, but that proposal is seriously flawed. In any inheritance tax model, scholars should expect to see significantly decreased compliance rates and increased administrative costs because, by focusing on the transferees instead of on the transferor, an inheritance tax would multiply the number oftaxpayers subject to the tax. This Article reviews common characteristics ofexisting inheritance tax systems in the United States and internationally-particularly in Europe. In addition, the Article analyzes the novel Comprehensive Inheritance Tax (CIT) proposal, which combines some elements of existing inheritance tax systems with some features ofthe current transfer tax system and delivers the CIT through the federal income tax system. -

3 Inheritance Taxation

LWS Working Paper Series No. 35 Inheritance Taxation in Comparative Perspective Manuel Schechtl June 2021 Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), asbl Inheritance Taxation in Comparative Perspective Manuel Schechtl* May 25, 2021 Abstract The role of inheritances for wealth inequality has been frequently addressed. However, until recently, comparative data has been scarce. This paper compiles inheritance tax information from EY Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide and combines it with microdata from the Luxembourg Wealth Study. The results indicate substantial differences in the tax base and the distributional potential of inheritance taxation across countries. Keywords: taxes, wealth, inheritance, inheritance tax *Humboldt Universita¨t zu Berlin; Email: [email protected] 1 1 Introduction The relevance of inheritances for the wealth distribution remains a widely debated topic in the social sciences. Using different comparative data sources, previous studies highlighted the positive association between inheritances received and the wealth rank (Fessler and Schu¨rz 2018) or household net worth (Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein 2013). Recent research highlighted the contribution of transferred wealth to overall wealth inequality in this very journal (Nolan et al. 2021). These studies have generated important insights into the importance of inherited wealth beyond national case studies (Black et al. 2020) or economic models of estate taxation (De Nardi and Yang 2016). However, institutional characteristics, such as taxes on inheritances, are seldomly scrutinised. As a notable exemption, Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein examine the association of household net worth and the inheritance tax rate (2013). Due to the lack of detailed comparative data on the design of inheritance taxation, they include inheritance taxes measured as top marginal tax rate in their analysis. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 23 July 2019 The Mauritius Leaks have once again revealed the devastating impact of tax avoidance. ICRICT calls for multilateral accord to overhaul the international tax system, the end of tax havens, the adoption of a minimum global tax and the creation of a Global Asset Registry The Mauritius Leaks have once again highlighted how rich and powerful corporations and the super-rich skirt paying taxes, whether legally or illegally. The schemes are the same, as already revealed by anonymous sources through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Malta Files, Luxleaks, SwissLeaks, among others. This is the latest in a series of leak that demonstrate how broken the current international tax system is. Why Mauritius? Mauritius built its position as an offshore financial centre on being a hub for tax avoidance. First it enabled multinationals to avoid capital gains tax in India. Then it created schemes to offer multinationals a low rate (3%) on income they could attribute to their subsidiaries in Mauritius supposedly for providing services to related entities in other countries, especially in Africa, with which it negotiated tax treaties. Mauritius has an extensive set of tax treaties with African countries, ensuring that investment made in African countries (profits/capital gains on investments) can be routed via Mauritius to rich countries with no/little taxes paid. No capital gains tax, no inheritance tax, wealth or gift tax, no Controlled Foreign Companies legislation, no transfer pricing rules or thin capitalization rules, no withholding tax on dividends, interest and royalty payments, you name Mauritius doesn’t have it, no wonder it has been used so extensively as a tax haven hub to take money out of Africa and India. -

Sustainable Public Finance: Double Neutrality Instead of Double Dividend

Journal of Environmental Protection, 2016, 7, 145-159 Published Online February 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2016.72013 Sustainable Public Finance: Double Neutrality Instead of Double Dividend Dirk Loehr Trier University of Applied Sciences, Environmental Campus Birkenfeld, Birkenfeld, Germany Received 27 November 2015; accepted 31 January 2016; published 4 February 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract A common answer to the financial challenges of green transformation and the shortcomings of the current taxation system is the “double dividend approach”. Environmental taxes should either feed the public purse in order to remove other distorting taxes, or directly contribute to financing green transformation. Germany adopted the former approach. However, this article argues, by using the example of Germany, that “good taxes” in terms of public finance should be neutral in terms of environmental protection and vice versa. Neutral taxation in terms of environmental im- pacts can be best achieved by applying the “Henry George principle”. Additionally, neutral taxation in terms of public finance is best achieved if the revenues from environmental taxes are redistri- buted to the citizens as an ecological basic income. Thus, distortive effects of environmental charges in terms of distribution and political decision-making might be removed. However, such a financial framework could be introduced step by step, starting with a tax shift. Keywords Double Dividend, Double Neutrality, Tinbergen Rule, Henry George Principle, Ecological Basic Income 1. -

Bulletin No. 13 (Motor Vehicle Excise Tax & Personal Property Tax)

MAINE REVENUE SERVICES PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NO. 13 MOTOR VEHICLE EXCISE TAX & PERSONAL PROPERTY TAX REFERENCE: 36 M.R.S. §§ 1481 through 1491 December 9, 2019; replaces November 21, 2017 revision 1. General The motor vehicle excise tax is an annual tax imposed for the privilege of operating a motor vehicle on public roads. This bulletin discusses the applicability of motor vehicle excise tax to automobiles, buses, trucks, truck tractors, motorcycles, and special mobile equipment. Mobile homes, camper trailers, and aircraft are also subject to excise tax, but are not covered by this bulletin. Detailed information about the excise tax as applied to mobile homes and camper trailers may be found in Property Tax Bulletin No. 6 – Taxation of Mobile Homes and Camper Trailers. For information about the excise tax as applied to aircraft, contact the Property Tax Division using the contact information at the end of this bulletin. As a rule, a registered motor vehicle owned by a person on April 1 and on which an excise tax was paid is exempt from property taxes. A motor vehicle, for which an excise tax has not been paid before property taxes are committed is subject to property tax. The Secretary of State provides municipal excise tax collectors with standard vehicle registration forms for the collection of excise tax. 2. The Motor Vehicle Excise Tax A. When applicable. The excise tax on motor vehicles applies where the owner of the motor vehicle intends to use it on public roads during the year. B. Where excise tax is payable. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

INTRODUCTION DFK INTERNATIONAL Is an Organisation Whose Membership Consists of Independent Accounting Firms and Business Advisers Throughout the World

INTRODUCTION DFK INTERNATIONAL is an organisation whose membership consists of independent accounting firms and business advisers throughout the world. It is committed to meeting the needs of businesses and individuals with interests in more than one country. DFK INTERNATIONAL Member Firms provide international tax and accounting services and answers to questions on these subjects. The WORLDWIDE TAX OVERVIEW gives brief details on the taxation régimes in many nations of the world. The Member Firms of DFK INTERNATIONAL can provide additional information concerning taxation legislation in these and other territories upon request. The WORLDWIDE TAX OVERVIEW is published without responsibility on behalf of DFK INTERNATIONAL, its Directors and its Member Firms for loss occasioned by any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any information contained herein. Tax laws change frequently worldwide and some of the information contained herein may be impacted by treaties. You are advised to consult with your local DFK INTERNATIONAL Member or other tax adviser in connection with any data contained in this Overview. © DFK International 2017 Country Corporate Rates Individual Rates VAT Rates Types of Taxes Taxation of Non-Residents Depreciation Miscellaneous Argentina 35% 9%-35% 10.5%-21% Income, VAT, payroll, excise. Tax imposed on income Generally straight-line based Provinces may levy gross 15% on capital gains Tax on assets for companies from resources and activities on probable useful life receipts taxes. Branch profits Fiscal year end: derived from sales of and individuals within Argentina. Withholding tax on foreign company’s 31.12.2017 shares tax between 10%-35% on permanent establishment interests, rents, dividends is 35%. -

U.S.-France Estate Tax Treaty

U.S.-FRANCE ESTATE TAX TREATY Convention between the government of the United States of America and the government of the French Republic for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on estates, inheritances, and gifts signed at Washington on November 24, 1978, amended by the Protocol signed at Washington on December 8, 2004. The President of the United States of America and the President of the French Republic, desiring to conclude a convention for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on estates, inheritances, and gifts, have appointed for that purpose as their respective plenipotentiaries: The President of the United States of America: The Honorable George S. Vest, Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs, The President of the French Republic: His Excellency Francois de Laboulaye, Ambassador of France, who having communicated to each other their full powers, found in good and due form, have agreed upon the following provisions. Article 1 Estates and Gifts Covered (1) This Convention shall apply to estates of decedents whose domicile at death was in France and to estates of decedents which are subject to the taxing jurisdiction of the United States by reason of the decedent's domicile therein or citizenship thereof at death. (2) This Convention shall also apply to gifts of donors whose domicile at the time of making a gift was in France, and to gifts which are subject to the taxing jurisdiction of the United States by reason of the donor's domicile therein or citizenship thereof at the time of making of a gift. -

1 Virtues Unfulfilled: the Effects of Land Value

VIRTUES UNFULFILLED: THE EFFECTS OF LAND VALUE TAXATION IN THREE PENNSYLVANIAN CITIES By ROBERT J. MURPHY, JR. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Robert J. Murphy, Jr. 2 To Mom, Dad, family, and friends for their support and encouragement 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my chair, Dr. Andres Blanco, for his guidance, feedback and patience without which the accomplishment of this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. Dawn Jourdan and Dr. David Ling, for carefully prodding aspects of this thesis to help improve its overall quality and validity. I‟d also like to thank friends and cohorts, such as Katie White, Charlie Gibbons, Eric Hilliker, and my parents - Bob and Barb Murphy - among others, who have offered their opinions and guidance on this research when asked. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................... 9 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 10 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... 11 ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................