1 Virtues Unfulfilled: the Effects of Land Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Appeals Rules Procedures

Tax Appeals Tribunal Rules & Procedures The rules of the game February 2017 Glossary of terms KRA Kenya Revenue Authority TAT Tax Appeals Tribunal TATA Tax Appeals Tribunal Act TPA Tax Procedures Act VAT Value Added Tax 2 © Deloitte & Touche 2017 Definition of terms Tax decision means: a) An assessment; Tax law means: b) A determination of tax payable made to a a) The Tax Procedures Act; trustee-in-bankruptcy, receiver, or b) The Income Tax Act, Value Added liquidator; Tax Act, and Excise Duty Act; and c) A determination of the amount that a tax c) Any Regulations or other subsidiary representative, appointed person, legislation made under the Tax director or controlling member is liable Procedures Act or the Income Tax for under specified sections in the TPA; Act, Value Added Tax Act, and Excise d) A decision on an application by a Duty Act. taxpayer to amend their self-assessment return; Objection decision means: e) A refund decision; f) A decision requiring repayment of a The Commissioner’s decision either to refund; or allow an objection in whole or in part, or g) A demand for a penalty. disallow it. Appealable decision means: a) An objection decision; and b) Any other decision made under a tax law but excludes– • A tax decision; or • A decision made in the course of making a tax decision. 3 © Deloitte & Touche 2017 Pre-objection process; management of KRA Audit KRA Audit Notes The TPA allows the Commissioner to issue to • The KRA Audits are a tax payer a default assessment, amended undertaken by different assessment or an advance assessment departments of the KRA that (Section 29 to 31 TPA). -

Econ 230A: Public Economics Lecture: Tax Incidence 1

Econ 230A: Public Economics Lecture: Tax Incidence 1 Hilary Hoynes UC Davis, Winter 2013 1These lecture notes are partially based on lectures developed by Raj Chetty and Day Manoli. Many thanks to them for their generosity. Hilary Hoynes () Incidence UCDavis,Winter2013 1/61 Outline of Lecture 1 What is tax incidence? 2 Partial Equilibrium Incidence I Theory: Kotliko¤ and Summers, Handbook of Public Finance, Vol 2 I Empirical Applications: Doyle and Samphantharak (2008), Hastings and Washington 3 General Equilibrium Incidence – WILL NOT COVER 4 Capitalization & Asset Market Approach I Empirical Application: Linden and Rocko¤ (2008) 5 Mandated Bene…ts I Theory: Summers (1989) I Empirical Application: Gruber (1994) Hilary Hoynes () Incidence UCDavis,Winter2013 2/61 1. What is tax incidence? Tax incidence is the study of the e¤ects of tax policies on prices and the distribution of utilities/welfare. What happens to market prices when a tax is introduced or changed? Examples: I what happens when impose $1 per pack tax on cigarettes? Introduce an earnings subsidy (EITC)? provide a subsidy for food (food stamps)? I e¤ect on price –> distributional e¤ects on smokers, pro…ts of producers, shareholders, farmers,... This is positive analysis: typically the …rst step in policy evaluation; it is an input to later thinking about what policy maximizes social welfare. Empirical analysis is a big part of this literature because theory is itself largely inconclusive about magnitudes, although informative about signs and comparative statics. Hilary Hoynes () Incidence UCDavis,Winter2013 3/61 1. What is tax incidence? (cont) Tax incidence is not an accounting exercise but an analytical characterization of changes in economic equilibria when taxes are changed. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

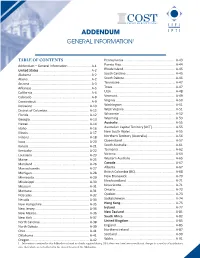

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

An Analysis of a Consumption Tax for California

An Analysis of a Consumption Tax for California 1 Fred E. Foldvary, Colleen E. Haight, and Annette Nellen The authors conducted this study at the request of the California Senate Office of Research (SOR). This report presents the authors’ opinions and findings, which are not necessarily endorsed by the SOR. 1 Dr. Fred E. Foldvary, Lecturer, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Colleen E. Haight, Associate Professor and Chair, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Annette Nellen, Professor, Lucas College of Business, San Jose State University, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank the Center for California Studies at California State University, Sacramento for their [email protected]; Dr. Colleen E. Haight, Associate Professor and Chair, Economics Department, San Jose State University, [email protected]; Dr. Annette Nellen, Professor, Lucas College of Business, San Jose State University, [email protected]. The authors wish to thank the Center for California Studies at California State University, Sacramento for their funding. Executive Summary This study attempts to answer the question: should California broaden its use of a consumption tax, and if so, how? In considering this question, we must also consider the ultimate purpose of a system of taxation: namely to raise sufficient revenues to support the spending goals of the state in the most efficient manner. Recent tax reform proposals in California have included a business net receipts tax (BNRT), as well as a more comprehensive sales tax. However, though the timing is right, given the increasingly global and digital nature of California’s economy, the recent 2008 recession tabled the discussion in favor of more urgent matters. -

Incidence of Value Added Tax, Effects and Implications

International Journal of Economics and Finance; Vol. 10, No. 10; 2018 ISSN 1916-971X E-ISSN 1916-9728 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Incidence of Value Added Tax, Effects and Implications George Obeng1,2 1 University of Education, Winneba, Ghana 2 Faculty of Business Education, College of Technology Education Kumasi, Kumasi, Ghana Correspondence: George Obeng, University of Education, Winneba; Department of Accounting Education, Faculty of Business Education, College of Technology Education Kumasi, P. O Box 1277, Kumasi, Ghana. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 31, 2018 Accepted: September 4, 2018 Online Published: September 15, 2018 doi:10.5539/ijef.v10n10p52 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v10n10p52 Abstract The current debate in the field of taxation and public finance is the concern of Value Added Tax (VAT) being inflationary and who the incidence or burden of payment falls. The implication from available literature and studies points to the fact that VAT can impact negatively on production and consumption, stifling free flow of economic activities. Literature is reviewed to find out the incidence of VAT and its implications on the firm and the consumer. It is established that VAT is not a cost to the business firm to make it inflationary but a charge independent of its pricing mechanism. It is also not extra cost to the consumer but part appropriation of the economic resource flow accruing to the consumer to settle the legitimate obligation of financing public expenditure. The paper concludes that the incidence of the tax is on the consumer and VAT is not inflationary but a means of tax optimality to stabilize the system in the event of market failure. -

Relationship Between Tax and Price and Global Evidence

Relationship between tax and price and global evidence Introduction Taxes on tobacco products are often a significant component of the prices paid by consumers of these products, adding over and above the production and distribution costs and the profits made by those engaged in tobacco product manufacturing and distribution. The relationship between tax and price is complex. Even though tax increase is meant to raise the price of the product, it may not necessarily be fully passed into price increase due to interference by the industry driven by their profit motive. The industry is able to control the price to certain extent by maneuvering the producer price and also the trade margin through transfer pricing. This presentation is devoted to the structure of taxes on tobacco products, in particular of excise taxes. Outline Tax as a component of retail price Types of taxes—excise tax, import duty, VAT, other taxes Basic structures of tobacco excise taxes Types of tobacco excise systems Tax base under ad valorem excise tax system Comparison of ad valorem and specific excise regimes Uniform and tiered excise tax rates Tax as a component of retail price Domestic product Imported product VAT VAT Import duty Total tax Total tax Excise tax Excise tax Wholesale price Retail Retail price Retail & retail margin Wholesale Producer Producer & retail margin Industry profit Importer's profit price CIF value Cost of production Excise tax, import duty, VAT and other taxes as % of retail price of the most sold cigarettes brand, 2012 Total tax -

Is There Room for a Room‐Tax in the Canary Islands?

Received: 22 June 2020 Revised: 13 January 2021 Accepted: 13 January 2021 DOI: 10.1002/jtr.2438 RESEARCH ARTICLE Is there room for a room-tax in the Canary Islands? Francisco López-del-Pino1 | Jose M. Grisolía1,2 | Juan de Dios Ortúzar3 1Applied Economics Department, Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain), Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain 2Nottingham University Business School China, The University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China 3Transport Engineering and Logistics, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile Correspondence Jose M. Grisolía, The University of Nottingham Ningbo China Room 369, Trent Building 199 Taikang East Road Ningbo, 315100, China. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS: discrete choice analysis, room-tax, stated preferences, tourism externalities 1 | INTRODUCTION A great variety of taxes is applied in the tourism industry (Durán Román, Cárdenas García, & Pulido Fernández, 2020; García, March- Tourism ranks among the most important economic activities in the ena, & Morilla, 2018; Gooroochurn & Sinclair, 2005) and these can be world. Recent figures from the World Tourism Organisation applied by governments to raise funds to offset the environmental (UNWTO, 2018) show that the number of international tourist trips impacts of tourism, as shown by Durán Román et al. (2020) in their reached nearly 1.4 billion in 2018, generating an economic impact review of tourism taxes in the top 50 tourist destinations. The estimated in US$ 1.7 billion (and 10 per cent of the jobs in the world). OECD (2014, page 76) defines tourism taxes as ‘the indirect taxes, Despite the fast growth of many competitive destinations, Europe is taxes and tributes that mainly affect the activities related to tourism’ still the main tourist destination with 51% of arrivals and 39% of the and classifies them into the following types: total income generated by international tourism. -

Whose 'Treasure Islands'? the Role of Tax Havens in the Global Economy

(C) Tax Analysts 2012. All rights reserved. does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Whose ‘Treasure Islands’? The Role of Tax Havens in The Global Economy by Robert T. Kudrle Robert T. Kudrle is the Orville and Jane Freeman Professor of International Trade and Investment Policy with the Hubert Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs and the Law School at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. A version of this article was presented at the 53rd Annual Convention of the International Studies Asso- ciation in San Diego on April 1-4, 2012. wo recent works with the same title suggest radi- In movies and novels, tax havens are often set- Tcally different views of the role of tax havens in tings for shady international deals; in practice the global economy. In late 2010, James R. Hines Jr. they are rather less flashy. Tax havens are coun- (2010) made the case for a largely beneficial role. Ac- tries or territories that offer low tax rates and fa- cording to Hines, the tax havens improve markets: they vorable regulatory environment to foreign inves- facilitate direct investment by improving the attraction tors....Taxhavensarealso known as ‘‘offshore of high-corporate-tax states for real investment, and centers’’ or ‘‘international financial centers,’’ they may shore up rather than degrade corporate tax phrases that may carry slightly differing connota- collections by high-corporate-income states such as the tions but nonetheless are used almost inter- U.S. They also seem to improve the competitiveness of changeably with ‘‘tax havens.’’ [P. 104.] national financial institutions and hence facilitate port- folio capital provision in both rich and poor countries. -

Transfer of Ownership Guidelines

Transfer of Ownership Guidelines PREPARED BY THE MICHIGAN STATE TAX COMMISSION Issued October 30, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Information 3 Transfer of Ownership Definitions 4 Deeds and Land Contracts 4 Trusts 5 Distributions Under Wills or By Courts 8 Leases 10 Ownership Changes of Legal Entities (Corporations, Partnerships, Limited Liability Companies, etc.) 11 Tenancies in Common 12 Cooperative Housing Corporations 13 Transfer of Ownership Exemptions 13 Spouses 14 Children and Other Relatives 15 Tenancies by the Entireties 18 Life Leases/Life Estates 19 Foreclosures and Forfeitures 23 Redemptions of Tax-Reverted Properties 24 Trusts 25 Court Orders 26 Joint Tenancies 27 Security Interests 33 Affiliated Groups 34 Normal Public Trades 35 Commonly Controlled Entities 35 Tax-Free Reorganizations 37 Qualified Agricultural Properties 38 Conservation Easements 41 Boy Scout, Girl Scout, Camp Fire Girls 4-H Clubs or Foundations, YMCA and YWCA 42 Property Transfer Affidavits 42 Partial Uncapping Situations 45 Delayed Uncappings 46 Background Information Why is a transfer of ownership significant with regard to property taxes? In accordance with the Michigan Constitution as amended by Michigan statutes, a transfer of ownership causes the taxable value of the transferred property to be uncapped in the calendar year following the year of the transfer of ownership. What is meant by “taxable value”? Taxable value is the value used to calculate the property taxes for a property. In general, the taxable value multiplied by the appropriate millage rate yields the property taxes for a property. What is meant by “taxable value uncapping”? Except for additions and losses to a property, annual increases in the property’s taxable value are limited to 1.05 or the inflation rate, whichever is less. -

The Cost of the Vote: Poll Taxes, Voter Identification Laws, and the Price of Democracy

File: Ellis final for Darby Created on: 4/9/2009 8:17:00 PM Last Printed: 5/19/2009 1:10:00 PM THE COST OF THE VOTE: POLL TAXES, VOTER IDENTIFICATION LAWS, AND THE PRICE OF DEMOCRACY ATIBA R. ELLIS† INTRODUCTION The election of Barack Obama as the forty-fourth President of the United States represents both the completion of a historical campaign season and a triumph of the Civil Rights revolution of the twentieth cen- tury. President Obama’s 2008 campaign, along with the campaigns of Senators Hillary Rodham Clinton and John McCain, was remarkable in both the identities of the politicians themselves1 and the attention they brought to the political process. In particular, Obama attracted voters from populations which have not been traditionally represented in na- tional politics. His run was hallmarked, in large part, by significant grassroots fundraising, a concerted effort to generate popular appeal, and, most important, massive voter turnout efforts.2 As a result, this election cycle generated significant increases in participation during the primary season.3 Turnout in the general election did not meet anticipated record † Legal Writing Instructor, Howard University School of Law. J.D., M.A., Duke Univer- sity, 2000. An early version of this paper was presented at the Writer’s Workshop of the Legal Writing Institute in summer 2007. Later versions were presented at the November 2007 Howard University School of Law faculty colloquy and the September 2008 Northeast People of Color Legal Scholarship Conference. I gratefully acknowledge Andrew Taslitz, Sherman Rogers, Derek Black, Paulette Caldwell, Phoebe Haddon, and Daniel Tokaji for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.