A Global Compendium and Meta-Analysis of Property Tax Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COLLECTING TAXES TECHNICAL NOTE Leadership in Public Financial Management II (LPFM II)

LPFMII-15-007 COLLECTING TAXES TECHNICAL NOTE Leadership in Public Financial Management II (LPFM II) Date: June 2018 i DISCLAIMER This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. This publication was produced by Nathan Associates Inc. for the United States Agency for International Development CONTENTS Contents Acronyms 2 Introduction 1 Indicator Definitions and Sources 1 Tax Performance 1 Tax Administration 6 Country Notes 10 Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank CIT Corporate Income Tax CTD Collecting Taxes Database FAD Fiscal Affairs Department of the International Monetary Fund GDP Gross Domestic Product GFS Government Financial Statistics GNI Gross National Income GST Goods and Services Tax IAMTAX Integrated Assessment Model for Tax ICRG International Country Risk Guide (of the PRS Group) ICTD International Centre for Tax and Development IMF International Monetary Fund IT Information Technology LPFM II Leadership in Public Financial Management II LTU Large Taxpayer Unit ODA Official Development Assistance OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OLS Ordinary least squares (estimation technique) PFM Public financial management PIT Personal Income Tax RA-FIT Revenue Administration’s Fiscal Information Tool TADAT Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool USAID United States Agency -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

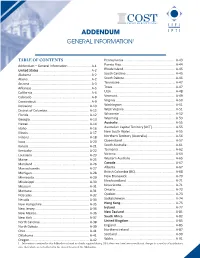

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

1 Progressive Taxation in Developing Economies

1 Progressive Taxation in Developing Economies: The Experience of China and India By Michael A. Livingston1 The concept of fairness in taxation is as old as the Bible, and applies to young or developing economies no less than large industrial democracies. Yet the debate on progressive (and especially progressive income) taxation has been conducted primarily in the wealthier countries. This results in part from experience: the most advanced and frequently studied progressive tax systems have been in developed countries, and the principal theoretical work was done in them. There is also a certain condescension here, a sense that poorer countries can perhaps not afford too much progressivity, and should content themselves with the collection of sufficient tax revenues—no small task in its own right—without indulging the “luxury” of a progressive or redistributive tax system. Yet tax equity is an issue that applies to all societies, and there is no inherent reason that it should be less important in a new or developing country than a more established nation. This paper considers the issue of progressive taxation and tax equity in younger, developing economies. The issue being extremely broad, it is necessary at the outset to impose some limitations. Thus I will limit myself to tax rather than spending policy and, within the tax system, provide special emphasis on progressive income taxes, although I am well aware that the income tax is only one of several revenue sources and, in many developing countries, is less important than other, less high-profile taxes. I will likewise eschew a statistical evaluation of progressivity, which I am in any case ill-equipped to do, in favor of an abstract but I hope engaging discussion of the issue in theoretical terms. -

A Study and Comparison of the Consumption Basis of Taxation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1964 A Study and Comparison of the Consumption Basis of Taxation Douglas Wayne Blevins College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Finance Commons Recommended Citation Blevins, Douglas Wayne, "A Study and Comparison of the Consumption Basis of Taxation" (1964). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624554. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-n8af-t738 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY AND COMPARISON OF THE CONSUMPTION BASIS OF TAXATION 1 FOREWORD This treatise is a study and comparison ©f the three measures of economic well-being and their use as bases far financing govern ment. Particular emphasis is given to the study ©f the consumption basis ef taxation. Submitted in compliance with the requirements for the Master ef Arts degree in Taxation. Douglas W. Blevins 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Part I. Introduction. A. Sources of Revenue. B. Principles ef taxation. 1. Canons ef Adam Smith. 2* Characteristics ef tax systems. % Economic effects. 4. E quity. 5. Compliance. 6. Shifting and incidence. Part II. Measures ef Economic Well-Being. A. Current income as a measure. 1. Income. 2. Definition ef income. a. The economic definition. b. The tax definition. -

Global Guide to M&A

GLOBAL GUIDE TO M&A TAX 2018 EDITION CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................................................3 COUNTRY OVERVIEWS .....................................................................................................................................................5 ARGENTINA ..........................................................................................................................................................................6 AUSTRIA .................................................................................................................................................................................19 BELGIUM .............................................................................................................................................................................. 32 BRAZIL ................................................................................................................................................................................. 42 CANADA ............................................................................................................................................................................... 51 CHILE ....................................................................................................................................................................................61 COLOMBIA ..........................................................................................................................................................................70 -

To View a PDF of This Article, Please Click Here

GLOBAL TAX WEEKLY ISSUE 134 | JUNE 4, 2015 a closer look SUBJECTS TRANSFER PRICING INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY VAT, GST AND SALES TAX CORPORATE TAXATION INDIVIDUAL TAXATION REAL ESTATE AND PROPERTY TAXES INTERNATIONAL FISCAL GOVERNANCE BUDGETS COMPLIANCE OFFSHORE SECTORS MANUFACTURING RETAIL/WHOLESALE INSURANCE BANKS/FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS RESTAURANTS/FOOD SERVICE CONSTRUCTION AEROSPACE ENERGY AUTOMOTIVE MINING AND MINERALS ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA OIL AND GAS COUNTRIES AND REGIONS EUROPE AUSTRIA BELGIUM BULGARIA CYPRUS CZECH REPUBLIC DENMARK ESTONIA FINLAND FRANCE GERMANY GREECE HUNGARY IRELAND ITALY LATVIA LITHUANIA LUXEMBOURG MALTA NETHERLANDS POLAND PORTUGAL ROMANIA SLOVAKIA SLOVENIA SPAIN SWEDEN SWITZERLAND UNITED KINGDOM EMERGING MARKETS ARGENTINA BRAZIL CHILE CHINA INDIA ISRAEL MEXICO RUSSIA SOUTH AFRICA SOUTH KOREA TAIWAN VIETNAM CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN BOSNIA CROATIA FAROE ISLANDS GEORGIA KAZAKHSTAN MONTENEGRO NORWAY SERBIA TURKEY UKRAINE UZBEKISTAN ASIA-PAC AUSTRALIA BANGLADESH BRUNEI HONG KONG INDONESIA JAPAN MALAYSIA NEW ZEALAND PAKISTAN PHILIPPINES SINGAPORE THAILAND AMERICAS BOLIVIA CANADA COLOMBIA COSTA RICA ECUADOR EL SALVADOR GUATEMALA PANAMA PERU PUERTO RICO URUGUAY UNITED STATES VENEZUELA MIDDLE EAST ALGERIA BAHRAIN BOTSWANA DUBAI EGYPT ETHIOPIA EQUATORIAL GUINEA IRAQ KUWAIT MOROCCO NIGERIA OMAN QATAR SAUDI ARABIA TUNISIA LOW-TAX JURISDICTIONS ANDORRA ARUBA BAHAMAS BARBADOS BELIZE BERMUDA BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS CAYMAN ISLANDS COOK ISLANDS CURACAO GIBRALTAR GUERNSEY ISLE OF MAN JERSEY LABUAN LIECHTENSTEIN MAURITIUS MONACO TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS VANUATU GLOBAL TAX WEEKLY a closer look Global Tax Weekly – A Closer Look Combining expert industry thought leadership and team of editors outputting 100 tax news stories a the unrivalled worldwide multi-lingual research week. GTW highlights 20 of these stories each week capabilities of leading law and tax publisher Wolters under a series of useful headings, including industry Kluwer, CCH publishes Global Tax Weekly –– A Closer sectors (e.g. -

Ecotaxes: a Comparative Study of India and China

Ecotaxes: A Comparative Study of India and China Rajat Verma ISBN 978-81-7791-209-8 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. ECOTAXES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIA AND CHINA1 Rajat Verma2 Abstract This paper attempts to compare various forms of ecotaxes adopted by India and China in order to reduce their carbon emissions by 2020 and to address other environmental issues. The study contributes to the literature by giving a comprehensive definition of ecotaxes and using it to analyse the status of these taxes in India and China. -

Historical Tax Law Changes Luxury Tax on Liquor

Historical Tax Law Changes Luxury Tax on Liquor Laws 1933, 1st Special Session, Chapter 18 levied the first Arizona state Luxury Tax on Liquor. The tax rates established by this law are shown below: 10¢ on each 16 ounces, or fractional part thereof, for malt extracts 10¢ on each container of spirituous liquor containing 16 ounces or less 10¢ on each 16 ounces of spirituous liquor in containers of more than 16 ounces 3¢ on each container of vinous liquor containing 16 ounces or less 3¢ on each 16 ounces of vinous liquor in containers of more than 16 ounces 5¢ on each gallon of malt liquor The tax was paid by the purchase of stamps affixed to each container of liquor and malt extract and canceled prior to sale. Taxes were payable to the State Tax Commission, prior to or at the time of the sale of the product. Of the total receipts collected, 96% was dedicated to the Board of Public Welfare and the remaining 4% was appropriated for the use of the State Tax Commission. The tax was a temporary tax and expired on March 1, 1935. (Effective June 28, 1933) Laws 1935, Chapter 14 extended the provisions of Laws 1933, 1st Special Session, Chapter 18 to May 1, 1935. (Effective February 20, 1935) Laws 1935, Chapter 78 permanently enacted the provisions of Laws 1933, 1st Special Session, Chapter 18, with respect to the Luxury tax on Liquor. The tax rates levied on containers of spirituous liquor and vinous liquor were replaced with the rates shown below: 5¢ on each container of spirituous liquor containing 8 ounces or less 5¢ on each 8 ounces of spirituous -

Alcohol Taxation in Australia

Alcohol taxation in Australia Report no. 03/2015 © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 ISBN 978-0-9925131-9-1 (Online) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/ Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are detailed on the following website: www.itsanhonour.gov.au/coat-arms Produced by: Parliamentary Budget Office Designed by: Studio Tweed Assistant Parliamentary Budget Officer Revenue Analysis Branch Parliamentary Budget Office Parliament House PO Box 6010 CANBERRA ACT 2600 Phone: (02) 6277 9500 Email: [email protected] Contents Foreword _______________________________________________________________ iv Overview ________________________________________________________________ v 1 Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 2 Alcohol taxation receipts _______________________________________________ 1 3 Australia’s system of alcohol taxation _____________________________________ 2 4 Recent history of alcohol taxation ________________________________________ 9 5 Conclusion __________________________________________________________ 10 Appendix A—Discretionary changes in excise rates since 1 January 2000 ____________ 11 References ______________________________________________________________ 14 iii Foreword This report examines the structure of alcohol taxation in Australia. The arrangements for taxing alcohol in Australia are complex and have evolved over many years. Alcohol is taxed on either a volume or a value basis, with a range of effective tax rates applying depending on the type of beverage and packaging, alcohol strength, place of manufacture and the method or scale of production. Consistent with the PBO’s mandate, the report presents a factual analysis and does not include policy recommendations. It is intended to help inform discussion of this important public policy issue. -

ECONOMIC COUNCILS in the DIFFERENT COUNTRIES of the WORLD I

Section of Economic Relations REVIEW OF THE ECONOMIC COUNCILS IN THE DIFFERENT COUNTRIES OF THE WORLD i Prepared for the Economic Committee | by Dr. Elli LINDNER League of Nations GENEVA 1932 [Communicated to the Council Official No. : C. 626. M. 308. 1932. II.B and the Members of the League.] [E. 795.] Series of League of Nations Publications II. ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL 1932. II.B. 10. CONTENTS. P age I. Introductory N ote by the Secretariat: 1. Resolution of the Twelfth A s s e m b ly .................................................. 5 2. E nquiry b y the Economic C o m m itte e ............................................. 6 3 . Principal Types of Economic C o u n cils............................................. 7 4. Co-operation of Economic Councils in the Work of the League of N a tio n s.................................................................................................. 7 II. P r e f a c e .............................................................................................................................. 9 III. Monographs concerning the Organisation and W orking of the E conomic Councils in Different Countries of the W orld : A. Africa: Union of South A f r i c a ...................................................................... 11 B. America: 1. A r g e n tin e ........................................................................................ 12 2. B r a z i l .................................................................................................. 13 3. C h i l e ...................... -

Business Cycles in a Small Open Economy Model: the Case of Hong Kong.∗

Business cycles in a small open economy model: The case of Hong Kong.∗ Paulina Etxeberria Garaigortay Amaia Izaz The University of the Basque Country. January, 2011 Abstract This paper analyzes the business cycle properties of the Hong Kong economy du- ring the 1982-2004 period, which includes the financial crisis experienced in Hong Kong in 1997-98. We show that output, output growth rate and real interest rates volatilities in Hong Kong are higher than their respective average volatilities among developed economies. In this paper, we build a stochastic neoclassical small open economy model that seeks to replicate the main business cycle characteristics of Hong Kong, and through which we try to quantify the role played by exogenous Total Factor Productivity and real interest rates shocks. The main finding is that, in order to ex- plain the Hong Kong business cycle characteristics, the trend volatility has to be higher than the volatility of the transitory fluctuations around the trend, and that the coun- try risk spread is the responsible for both the high variability and its countercyclicality. Keywords: Asian Financial Crisis, Small Open Economy, Neoclassical model. JEL Classification: E13, E32, F41. ∗We thank Cruz Angel´ Echevarr´ıa for useful comments. This paper was presented at the All China Economics (ACE) International Conference, Hong Kong, 2006, XXXIII Symposium of Economic Analysis, Spain, 2007, DEGIT XVI Dynamics, Economic Growth and International Trade, Los Angeles, USA, 2009. Financial support from Universidad del Pa´ısVasco MACLAB, project IT-241-07, and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovaci´on,project ECO2009-09732 are gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are the authors' responsibility.