Taxes in Canada’S Largest Metropolitan Areas?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laurentides-Horaire-88.Pdf

Principaux arrêts Service à la clientèle 88 Par écrit : exo.quebec/nousecrire 88 Saint-Eustache Par téléphone : 450 433-7873 Saint-Eustache Terminus Saint-Eustache Sans frais : 1 833 705-7873 Sainte-Thérèse Lundi au vendredi : 6 h à 20 h 30 Sainte-Thérèse Samedi, dimanche et jours fériés : 9 h à 17 h Boisbriand Chemin de la Grande-Côte Boisbriand Rosemère Rosemère Transport adapté Boulevard Labelle Les personnes handicapées ou à mobilité réduite peuvent, à certaines conditions, bénéficier d’un service de transport adapté. Horaire en vigueur à Gare Sainte-Thérèse Pour joindre le transport adapté : partir du 19 août 2019 450 433-4000 ou 1 877 433-4004 Collège Lionel-Groulx Taxi collectif Pour répondre aux besoins en transport dans certains secteurs à faible densité, un service de transport collectif effectué par taxi a été mis en place (ex. secteurs de Mirabel). Pour obtenir des renseignements supplémentaires, téléphonez au centre d’appels ou visitez le exo.quebec/laurentides. Jours fériés 2019 Pour ces journées, l'horaire en vigueur sera celui du samedi. 1er janvier Jour de l'An 2 janvier Lendemain du Jour de l’An 19 avril Vendredi saint 20 mai Journée nationale des patriotes 24 juin Fête nationale 1er juillet Fête du Canada 2 septembre Fête du Travail 14 octobre Action de grâces 25 décembre Jour de Noël 26 décembre Lendemain de Noël Édition : Juin 2019 AVIS : Nous nous faisons un devoir de respecter les horaires. Toutefois, Application mobile Chrono la congestion routière, les travaux de construction et les intempéries occasionnent des retards indépendants de notre volonté. -

Municipal Newsletter

VILLEPINCOURT.QC.CA Follow us on VILLEdePINCOURT info- NEW FAMILY YOGA (FREE) RÉCRÉAVÉLO-ZVP PINCOURT Municipal newsletter SUMMER 2019, VOLUME 28 YOUR TOWN POLITICSCOUNCIL Yvan Cardinal Mayor President of the Commission générale élargie Contact me: Diane Boyer [email protected] District: 4 514 453-4238 Presidente of the Commission d’administration et de finances Contact me: Alexandre Wolford [email protected] District: 1 438 397-7226 President of the Commission du déve- loppement durable Contact me: Claudine Girouard-Morel [email protected] District: 5 [email protected] Vice-president of the Commission de développement durable Contact me: Denise Bergeron [email protected] District: 2 514 501-0245 President of the Commission de développement social, des services communautaires et loisirs René Lecavalier Contact me: District: 6 [email protected] President of the Commission des 514 808-6257 infrastructures, des travaux publics et de l’aménagement du territoire Sam Ierfino Contact me: District: 3 [email protected] President of the Commission de sécu- 514 646-0720 rité publique Contact me: To see the complete profile of [email protected] your councillors, visit: 438 257-1134 www.villepincourt.qc.ca/en/16/town-council. COUNCIL MEETINGS, 7 p.m., Omni-Centre Next council meetings for 2019: • May 14 • June 11 • July 9 YOUR TOWN IN THE NEWS NEW REGULATION IN EFFECT PLASTIC BAG BAN IN RETAIL STORES On April 22, in honour of Earth Day, the Town of Pincourt adopted a new by-law prohibiting the use of single-use plas- tic shopping bags on its territory. -

Zones & Cities

Zones & Cities Cities and Zones For use with Long-Haul and Regional tariffs BC-6 BC-5 AB-8 AB-4 NL-2 AB-5 AB-7 BC-8 AB-6 SK-4 NL-3 NL-1 BC-1 AB-1 SK- 4 AB-3 SK-3 BC-2 PE-2 BC-7 MB-4 PE-2 PE-1 BC-3 QC-7 MB-1 NS-4 BC- 4 AB-2 SK-1 ON-14 NB-3 SK-2 ON-13 SK-2 QC-6 NB-1 MB-3 QC-4 NS-3 MB-2 QC-3 QC-2 NB-2 NS-1 NS-2 ON-11 QC-5 ON-12 ON-10 QC-1 ON-9 ON-6 ON-5 ON-8 ON-7 ON-1 ON-2 ON-3 ON-4 We’ve got Canada covered — from the Great Lakes to the Yukon and coast to coast. BC-6 BC-5 AB-8 AB-4 NL-2 AB-5 AB-7 BC-8 AB-6 SK-4 NL-3 NL-1 BC-1 AB-1 SK- 4 AB-3 SK-3 BC-2 PE-2 BC-7 MB-4 PE-2 PE-1 BC-3 QC-7 MB-1 NS-4 BC- 4 AB-2 SK-1 ON-14 NB-3 SK-2 ON-13 SK-2 QC-6 NB-1 MB-3 QC-4 NS-3 MB-2 QC-3 QC-2 NB-2 NS-1 NS-2 ON-11 QC-5 ON-12 ON-10 QC-1 ON-9 ON-6 ON-5 ON-8 ON-7 ON-1 ON-2 ON-3 ON-4 Cities & Zones ALBERTA Kitimat BC-X Deer Lake NL-3 Kingston ON-8 Brossard QC-1 Repentigny QC-3 Airdrie AB-1 Ladysmith BC-7 Gander NL-2 Kirkland Lake ON-X Brownsburg-Chatham QC-3 Richelieu QC-4 Banff AB-2 Langford BC-7 Grand Falls - Windsor NL-2 Kitchener ON-2 Cabano QC-X Rimouski QC-X Bonnyville AB-5 Langley BC-1 Happy Valley - Goose Bay NL-X London ON-3 Candiac QC-1 Rivière-du-Loup QC-6 Brooks AB-3 Mackenzie BC-X Harbour Grace NL-X Markham ON-1 Carignan QC-1 Roberval QC-X Calgary AB-1 Merritt BC-X Marystown NL-X Midland ON-6 Carleton-sur-mer QC-X Rosemère QC-3 Camrose AB-5 Mission BC-2 Mount Pearl NL-1 Mississauga ON-1 Chambly QC-4 Rouyn-Noranda QC-X Canmore AB-2 Nanaimo BC-7 Placentia NL-X Newmarket ON-6 Chandler QC-X Saguenay QC-7 Coaldale AB-2 Nelson BC-4 Stephenville NL-3 Niagara -

3. the Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust by Max Beer

Curr Psychol DOI 10.1007/s12144-007-9017-3 The Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust Max Beer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract In 1993 Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in Germany. At the same time, in Canada in general and in Montreal in particular, anti-Semitism was becoming more widespread. The Canadian Jewish Congress, as a result of the growing tension in Europe and the increase in anti-Semitism at home, was reborn in 1934 and became the authoritative voice of Canadian Jewry. During World War II the Nazis embarked on a campaign that resulted in the systematic extermination of millions of Jews. This article focuses on the Montreal Jewish community, its leadership, and their response to the fate of European Jewry. The study pays particular attention to the Canadian Jewish Congress which influenced the outlook of the community and its subsequent actions. As the war progressed, loyalty to Canada and support for the war effort became the overriding issues for the community and the leadership and concern for their European brethren faded into the background. Keywords Anti-Semitism . Holocaust . Montreal . Quebec . Canada . Bronfman . Uptowners . Downtowners . Congress . Caiserman The 1930s, with the devastating worldwide economic depression and the emergence of Nazism in Germany, set the stage for a war that would result in tens of millions of deaths and the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. The decade marked a complete stoppage of Jewish immigration to Canada, an increase in anti-Semitism on the North American continent, and the revival of the Canadian Jewish Congress as the voice for the Canadian Jewish community. -

Demographic Context

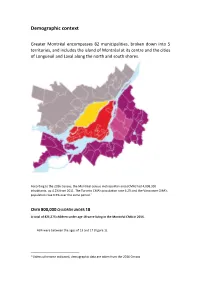

Demographic context Greater Montréal encompasses 82 municipalities, broken down into 5 territories, and includes the island of Montréal at its centre and the cities of Longueuil and Laval along the north and south shores. According to the 2016 Census, the Montréal census metropolitan area (CMA) had 4,098,930 inhabitants, up 4.2% from 2011. The Toronto CMA’s population rose 6.2% and the Vancouver CMA’s population rose 6.5% over the same period.1 OVER 800,000 CHILDREN UNDER 18 A total of 821,275 children under age 18 were living in the Montréal CMA in 2016. — 46% were between the ages of 13 and 17 (Figure 1). 1 Unless otherwise indicated, demographic data are taken from the 2016 Census. Figure 1.8 Breakdown of the population under the age of 18 (by age) and in three age categories (%), Montréal census metropolitan area, 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). 2016 Census, product no. 98-400-X2016001 in the Statistics Canada catalogue. The demographic weight of children under age 18 in Montréal is higher than in the rest of Quebec, in Vancouver and in Halifax, but is lower than in Calgary and Edmonton. While the number of children under 18 increased from 2001 to 2016, this group’s demographic weight relative to the overall population gradually decreased: from 21.6% in 2001, to 20.9% in 2006, to 20.3% in 2011, and then to 20% in 2016 (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 Demographic weight (%) of children under 18 within the overall population, by census metropolitan area, Canada, 2011 and 2016 22,2 22,0 21,8 21,4 21,1 20,8 20,7 20,4 20,3 20,2 20,2 25,0 20,0 19,0 18,7 18,1 18,0 20,0 15,0 10,0 5,0 0,0 2011 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). -

Zone 8 29 September 2021 | 05 H 30 Zone 8

Zone 8 29 September 2021 | 05 h 30 Zone 8 Maps Zone map (PDF 884 Kb) Interactive map of fishing zones Fishing periods and quotas See the zone's fishing periods and quotas Zone's fishing periods, limits and exceptions (PDF) Printable version. Length limits for some species It is prohibited to catch and keep or have in your possession a fish from the waters specified that does not comply with the length limits indicated for your zone. If a fish species or a zone is not mentioned in the table, no length limit applies to the species in this zone. The fish must be kept in a state allowing its identification. Walleye May keep Walleye between 37 cm and 53 cm inclusively No length limit for sauger. State of fish Whole, gutted or wallet filleted Learn how to distinguish walleye from sauger. Muskellunge May keep Muskellunge all length Exceptions May keep muskellunge 111 cm or more in the portion of the St. Lawrence River located in zone 8, including the following water bodies: lac Saint-Louis, rapides de Lachine, bassin La Zone 8 Page 2 29 September 2021 | 05 h 30 Prairie, rivière des Mille Îles, rivière des Prairies, lac des Deux Montagnes, and the part of the rivière Outaouais located in zone 8. May keep muskellunge 137 cm or more in lac Saint-François. State of fish Whole or gutted Lake trout (including splake trout) May keep Lake trout 60 cm or more State of fish Whole or gutted, only where a length limit applies. Elsewhere, lake trout may be whole or filleted. -

Your Gateway to North American Markets

YOUR GATEWAY TO NORTH AMERICAN MARKETS Biopharmaceuticals Medical technologies Contract research organizations Incubators and accelerators Research centers Rental and construction opportunities GREATER MONTREAL A NETWORK OF INNOVATIVE BUSINESSES Private and public contract research organizations (CRO), medication manufacturers and developers (CMO and CDMO). A HOSPITAL NETWORK Over 30 hospitals, 2 of which are university “super hospitals”: the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the McGill University Health Centre. A BUSINESS NETWORK BIOQuébec, Montréal In Vivo, Montréal International, Medtech Canada, etc. Biotech City supports the creation and growth of life sciences businesses by offering them an exceptional working environment. Rental spaces, laboratories, land, etc. Access to a network of R&D _ Assistance with funding applications; professionals and partners _ Financing programs available to _ A skilled workforce; SMEs; _ Collaboration between universities; _ Property tax credit; _ Events and networking (local _ International mobility support. ecosystem); _ Venture capital. A SEAMLESS VALUE CHAIN FROM DISCOVERY TO PRODUCTION The result of a partnership between the Ville de Laval and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS), Biotech City is a business and scientific research centre focused on business development, innovation and business competitiveness. Strategically located near Montreal, Biotech City is also close to several airports. 110 5,500 4.5 1.2 businesses jobs billion in private millions of (multinationals, investments sq. m. dedicated SMEs, start-ups) since 2001 to life sciences and high-tech innovation VANCOUVER 5 h 30 min LAVAL MONTREAL TORONTO 1 h 10 min BOSTON 1 h 15 min NEW YORK 1 h 25 min SAN FRANCISCO 6 h 25 min RALEIGH-DURHAM 3 h 30 min QUEBEC BIOTECHNOLOGY INNOVATION CENTRE (QBIC) The QBIC has acted as an incubator for life sciences and health technologies companies for the past 25 years. -

Inventaire Du Patrimoine Bâti

MRC de Thérèse-De Blainville Inventaire du patrimoine bâti MRC de Thérèse-De Blainville Inventaire du patrimoine bâti Maison du docteur Avila Larose Domaine Louis-Philippe Hébert Maison Thomas-Kimpton 169, boulevard Sainte-Anne, 501, boulevard Adolphe-Chapleau, ou villa William-Brennan 463, rue de l’Île-Bélair Ouest, 597, rue du Chêne, Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines Bois-des-Filion 10-12, rue Saint-Charles, Rosemère Bois-des-Filion Sainte-Thérèse Ancien séminaire Grange-étable de Sainte-Thérèse, devenu le Maison Garth Église de Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines Maison Hubert-Maisonneuve du Domaine Garth Collège Lionel-Groulx 100, chemin de la Grande-Côte, 129, boulevard Sainte-Anne, 369, chemin de la Grande-Côte, 100, chemin de la Grande-Côte, 100, rue Duquet, Lorraine Sainte-Anne-des-Plainese Rosemère Lorraine Sainte-Thérèse Maison Paquin-McNabb Maison Bélanger 243, chemin du Bas-de- Maison William-Miller 276, chemin de 274, chemin de la Grande-Côte, Sainte-Thérèse, 475, rue Émile-Nelligan, la Côte-Saint-Louis Est Boisbriand Blainville Boisbriand Blainville COMITÉ DE SUIVI Kamal El-Batal, directeur général MRC de Thérèse-De Blainville Guy Charbonneau, maire RÉALISATION Ville de Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines Claude Bergeron, conseiller en patrimoine culturel : Louis Dumas, adjoint au directeur gestion de projet, inventaire sur le terrain, évaluation Service de développement durable, Ville de Lorraine patrimoniale et rédaction Jean Goulet, directeur des études et communications Anne Plamondon, bachelière en histoire de l’art et Ville de Bois-des-Filion candidate à la maîtrise en histoire de l’art : inventaire Anne-Marie Larochelle, agente de développement sur le terrain, géolocalisation des éléments, saisie dans culturel, Service des arts et de la culture le fichier d’inventaire, collaboration à la rédaction Ville de Sainte-Thérèse Sarah Vachon-Bellavance, bachelière en histoire et Nous tenons à remercier M. -

Canada's Population 1

Canada’s Demographics Reading • Most standard textbooks on the geography of Canada have a population chapter Data Sources • Until September 2013 Census and StatsCan data was released to universities via E-STAT – Site discontinued • Data now available free on the web • Best to use the University’s on-line research guide Statscan Canada’s Population • Canada in 2016 had 36.3 million people • The birth rate is low, and falling – Except among aboriginal peoples • But Canada’s population still grew by 15% 2011-16 Canada’s Population • 2/3 of population growth now through immigration – From global and increasingly non-European sources – Immigrant and aboriginal fertility props up the birth rate • Canada had the fastest population growth in the G8 (5.9% in 2006-11, 15% 2011-16). Canada’s Population • Changes in Canada’s economy drive internal migration, and shift population growth – Nationally, growth connected to resource sector especially of energy resources – Decline of manufacturing jobs, locally, nationally • Population and employment shifts westwards to BC, Prairies. Population Size • Canada 1867: – 3.4 million people • Canada 2016: – 36.3 million people Population Distribution • Where do people live? • What kinds of settlements? Population Distribution • Population Density – People per unit of territory – Usually people/km2 • Canada 2011: – 33.5 Million people – 9.2 Million km2 of land area – 3.6 people/km2 Population Density Varies • Within Canada • 13.4 people/km2 in Ontario – Much higher in south, lower in north • 0.03 people/km2 in -

Cross-Border Group-Taxation and Loss-Offset in the EU - an Analysis for CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) and ETAS (European Tax Allocation System)

arqus Arbeitskreis Quantitative Steuerlehre www.arqus.info Diskussionsbeitrag Nr. 66 Claudia Dahle Michaela Bäumer Cross-Border Group-Taxation and Loss-Offset in the EU - An Analysis for CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) and ETAS (European Tax Allocation System) - April 2009 arqus Diskussionsbeiträge zur Quantitativen Steuerlehre arqus Discussion Papers in Quantitative Tax Research ISSN 1861-8944 Cross-Border Group-Taxation and Loss-Offset in the EU - An Analysis for CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) and ETAS (European Tax Allocation System) - Abstract The European Commission proposed to replace the currently existing Separate Accounting by an EU-wide tax system based on a Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB). Besides the CCCTB, there is an alternative tax reform proposal, the European Tax Allocation System (ETAS). In a dynamic capital budgeting model we analyze the impacts of selected loss-offset limitations currently existing in the EU under both concepts on corporate cross- border real investments of MNE. The analyses show that replacing Separate Accounting by either concept can lead to increasing profitability due to cross-border loss compensation. However, if the profitability increases, the study indicates that the main criteria of decisions on location are the tax rate divergences within the EU Member States. High tax rate differentials in the Member States imply significant redistribution of tax payments under CCCTB and ETAS. The results clarify that in both reform proposals tax payment reallocations occur in favor of the holding. National loss-offset limitations and minimum taxation concepts in tendency lose their impact on the profitability under both proposals. However, we found scenarios in which national minimum taxation can encroach upon the group level, although in our model the minimum taxation’s impacts seem to be slight. -

Becoming a Superior in the Congre´Gation De Notre-Dame of Montreal, 1693–1796

Power, Position and the pesante charge: Becoming a Superior in the Congre´gation de Notre-Dame of Montreal, 1693–1796 COLLEEN GRAY* Research surrounding convents in mediaeval Europe, post-Tridentine Latin America, and eighteenth-century Canada has argued that well-born religious women achieved top administrative positions within their respective institutions pri- marily due to their social and financial connections. This study of the Congre´gation de Notre-Dame in Montreal between 1693 and 1796, however, reveals that ordinary individuals were at the helm as superiors of this particular institution, and that they achieved this position largely as a result of their own demonstrated talents. This interpretation broadens the notion of an ancien re´gime in which wealth, patronage, and connections ruled the day to include the possibility that an individual’s abilities were also important. The study also demonstrates the persistent efficacy of empirical social history, when used in combination with other methodologies, in historical analysis. Les recherches sur les couvents de l’Europe me´die´vale, de l’Ame´rique latine post- tridentine et du Canada du XVIIIe sie`cle donnaient a` penser que les religieuses de bonne naissance obtenaient des postes supe´rieurs dans l’administration de leurs e´tablissements respectifs en raison surtout de leurs relations sociales et financie`res. Cette e´tude de la Congre´gation de Notre-Dame de Montre´al entre 1693 et 1796 re´ve`le toutefois que des femmes ordinaires ont e´te´ me`re supe´rieure de cet e´tablissement particulier et qu’elles acce´daient a` ce poste graˆce en bonne * Colleen Gray is adjunct professor in the Department of History at Queen’s University. -

Coverage Areas Map Coverage U.S

Coverage Areas Map Coverage U.S. Detailed Coverage Areas Colorado The system provides map coverage for Alabama Denver/Boulder/Colorado Springs/ the following 48 US states, and southern Ski Resorts Metro area - including Canada. The US map coverage consists Birmingham/Tuscaloosa Ft. Collins Huntsville of accurately mapped (verified) Connecticut metropolitan areas (in the following Mobile list), and a less accurate (unverified) Arizona Bridgeport Danbury rural database. Canada coverage Phoenix Metro consists of major metropolitan areas, Hartford Metro Sedona New Haven Metro and major roads connecting the Tucson metropolitan areas within about 100 Norwalk miles north of the U.S. border. If you Arkansas Stamford need additional North Canada coverage, Fayetteville Delaware you may purchase the gray Canadian Hot Springs Entire state - including Dover, DVD (see Obtaining a Navigation Little Rock Wilmington Metro area, New Castle Update DVD on page 109). See Map California County Overview on page 6 for a discussion of Bakersfield map coverage. Florida Fresno Cape Canaveral/Cocoa Beach/ Los Angeles/San Diego Metro The cities and metropolitan areas in the Titusville Merced Florida Keys following list are fully mapped. Only Modesto major streets, roads, and freeways have Fort Myers Metro area - including Sacramento Metro Naples been verified outside these areas. If your San Francisco Bay (approximately route passes through these areas, routing Fort Pierce Monterey to Sonoma) - including Gainesville may be limited in these areas, depending Monterey County and Hollister Unverified Jacksonville Metro - including St. on your routing choices (see San Luis Obispo Area Routing on page 89). Johns County Stockton Miami/Fort Lauderdale/West Palm Beach Metro Orlando/Daytona Beach/Melbourne area - including Osceola County Navigation System 111 Coverage Areas Pensacola Indiana Maryland Tallahassee Fort Wayne Baltimore/Washington D.C.