3. the Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust by Max Beer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorot: the Mcgill Undergraduate Journal of Jewish Studies Volume 15

Dorot: The McGill Undergraduate Journal of Jewish Studies Volume 15 – 2016 D O R O T: The McGill Undergraduate Journal of Jewish Studies D O R O T: The McGill Undergraduate Journal of Jewish Studies Published by The Jewish Studies Students’ Association of McGill University Volume 15 2016 Copyright © 2016 by the Jewish Studies Students’ Association of McGill University. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors included. They do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Jewish Studies or the Jewish Studies Students’ Association. ISSN 1913-2409 This is an annual publication of the Jewish Studies Students’ Association of McGill University. All correspondence should be sent to: 855 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3A 2T7 Editor in Chief Caroline Bedard Assistant Editors Akiva Blander Rayna Lew Copy Editors Lindsay MacInnis Patricia Neijens Cover Page Art Jennifer Guan 12 Table of Contents Preface i Introduction v To Emerge From the Ghetto Twice: Anti-Semitism and 1 the Search for Jewish Identity in Post-War Montreal Literature Madeleine Gomery The Origins of Mizrahi Socio-Political Consciousness 21 Alon Faitelis The “Israelization” of Rock Music and Political Dissent 38 Through Song Mason Brenhouse Grace Paley’s Exploration of Identity 54 Madeleine Gottesman The Failure of Liberal Politics in Vienna: 71 Alienation and Jewish Responses at the Fin-de-Siècle Jesse Kaminski Author Profiles 105 Preface Editor-in-chief, Caroline Bedard, and five contributors put together a terrific new issue of Dorot, the undergraduate journal of McGill’s Department of Jewish Studies. -

The Life and Teaching of Karl Marx

Routledge Revivals The Life and Teaching of Karl Marx First published in English in 1921, this work was originally written by renowned Marxist historian Max Beer to commemorate the centenary of Marx’s birth. It is a definitive biography, full of interesting personal details and a clear and comprehensive account of Marx’s economic and historical doctrines. A special feature of this unique work is the new light thrown on Marx’s attitude to the "Dictatorship of the Proletariat" and Bolshevist methods gen- erally. The Life and Teaching of Karl Marx Max Beer Translated by T. C. Partington & H. J. Stenning and revised by the author First published in English in 1921 This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. Disclaimer The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact. A Library of Congress record exists under LC Control Number: 22018875 ISBN 13: 978-0-415-67633-5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-67745-5 (pbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-203-80839-9 (ebk) THE LIFE AND TEACHING OF KARL MARX BY M. -

SFU Library Thesis Template

Linguistic variation and ethnicity in a super-diverse community: The case of Vancouver English by Irina Presnyakova M.A. (English), Marshall University, 2011 MA (Linguistics), Northern International University, 2004 BA (Education), Northern International University, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Irina Presnyakova 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Irina Presnyakova Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Thesis title: Linguistic variation and ethnicity in a super- diverse community: The case of Vancouver English Committee: Chair: Dean Mellow Associate Professor, Linguistics Panayiotis Pappas Supervisor Professor, Linguistics Murray Munro Committee Member Professor, Linguistics Cecile Vigouroux Examiner Associate Professor, French Alicia Wassink External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics University of Washington ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract Today, people with British/European heritage comprise about half (49.3%) of the total population of Metro Vancouver, while the other half is represented by visual minorities, with Chinese (20.6%) and South Asians (11.9%) being the largest ones (Statistics Canada 2017). However, non-White population are largely unrepresented in sociolinguistic research on the variety of English spoken locally. The objective of this study is to determine whether and to what extent young people with non-White ethnic backgrounds participate in some of the on-going sound changes in Vancouver English. Data from 45 participants with British/Mixed European, Chinese and South Asian heritage, native speakers of English, were analyzed instrumentally to get the formant measurements of the vowels of each speaker. -

Jewish Community Advocacy in Canada

JEWISH COMMUNITY ADVOCACY IN CANADA As the advocacy arm of the Jewish Federations of Canada, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs is a non-partisan organization that creates and implements strategies for the purpose of improving the quality of Jewish life in Canada and abroad, increasing support for Israel, and strengthening the Canada-Israel relationship. Previously, the Jewish community in Canada had been well served for decades by two primary advocacy organizations: Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) and Canada-Israel Committee (CIC). Supported by the organized Jewish community through Jewish Federations of Canada – UIA, these agencies responded to the needs and reflected the consensus within the Canadian Jewish Community. Beginning in 2004, the Canadian Council for Israel and Jewish Advocacy (CIJA) served as the management umbrella for CJC and CIC and, with the establishment of the University Outreach Committee (UOC), worked to address growing needs on Canadian campuses. Until 2011, each organization was governed and directed by independent Boards of Directors and professional staff. In 2011, these separate bodies were consolidated into one comprehensive and streamlined structure, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, which has been designed as the single address for all advocacy issues of concern to Canadian Jewry. The new structure provides for a robust, cohesive, and dynamic organization to represent the aspirations of Jewish Canadians across the country. As a non-partisan organization, the Centre creates and implements strategies to improve the quality of Jewish life in Canada and abroad, advance the public policy interests of the Canadian Jewish community, enhance ties with Jewish communities around the world, and strengthen the Canada-Israel relationship to the benefit of both countries. -

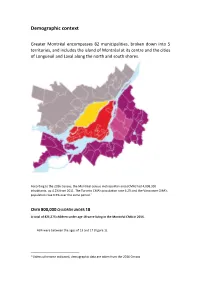

Demographic Context

Demographic context Greater Montréal encompasses 82 municipalities, broken down into 5 territories, and includes the island of Montréal at its centre and the cities of Longueuil and Laval along the north and south shores. According to the 2016 Census, the Montréal census metropolitan area (CMA) had 4,098,930 inhabitants, up 4.2% from 2011. The Toronto CMA’s population rose 6.2% and the Vancouver CMA’s population rose 6.5% over the same period.1 OVER 800,000 CHILDREN UNDER 18 A total of 821,275 children under age 18 were living in the Montréal CMA in 2016. — 46% were between the ages of 13 and 17 (Figure 1). 1 Unless otherwise indicated, demographic data are taken from the 2016 Census. Figure 1.8 Breakdown of the population under the age of 18 (by age) and in three age categories (%), Montréal census metropolitan area, 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). 2016 Census, product no. 98-400-X2016001 in the Statistics Canada catalogue. The demographic weight of children under age 18 in Montréal is higher than in the rest of Quebec, in Vancouver and in Halifax, but is lower than in Calgary and Edmonton. While the number of children under 18 increased from 2001 to 2016, this group’s demographic weight relative to the overall population gradually decreased: from 21.6% in 2001, to 20.9% in 2006, to 20.3% in 2011, and then to 20% in 2016 (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 Demographic weight (%) of children under 18 within the overall population, by census metropolitan area, Canada, 2011 and 2016 22,2 22,0 21,8 21,4 21,1 20,8 20,7 20,4 20,3 20,2 20,2 25,0 20,0 19,0 18,7 18,1 18,0 20,0 15,0 10,0 5,0 0,0 2011 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). -

Your Gateway to North American Markets

YOUR GATEWAY TO NORTH AMERICAN MARKETS Biopharmaceuticals Medical technologies Contract research organizations Incubators and accelerators Research centers Rental and construction opportunities GREATER MONTREAL A NETWORK OF INNOVATIVE BUSINESSES Private and public contract research organizations (CRO), medication manufacturers and developers (CMO and CDMO). A HOSPITAL NETWORK Over 30 hospitals, 2 of which are university “super hospitals”: the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the McGill University Health Centre. A BUSINESS NETWORK BIOQuébec, Montréal In Vivo, Montréal International, Medtech Canada, etc. Biotech City supports the creation and growth of life sciences businesses by offering them an exceptional working environment. Rental spaces, laboratories, land, etc. Access to a network of R&D _ Assistance with funding applications; professionals and partners _ Financing programs available to _ A skilled workforce; SMEs; _ Collaboration between universities; _ Property tax credit; _ Events and networking (local _ International mobility support. ecosystem); _ Venture capital. A SEAMLESS VALUE CHAIN FROM DISCOVERY TO PRODUCTION The result of a partnership between the Ville de Laval and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS), Biotech City is a business and scientific research centre focused on business development, innovation and business competitiveness. Strategically located near Montreal, Biotech City is also close to several airports. 110 5,500 4.5 1.2 businesses jobs billion in private millions of (multinationals, investments sq. m. dedicated SMEs, start-ups) since 2001 to life sciences and high-tech innovation VANCOUVER 5 h 30 min LAVAL MONTREAL TORONTO 1 h 10 min BOSTON 1 h 15 min NEW YORK 1 h 25 min SAN FRANCISCO 6 h 25 min RALEIGH-DURHAM 3 h 30 min QUEBEC BIOTECHNOLOGY INNOVATION CENTRE (QBIC) The QBIC has acted as an incubator for life sciences and health technologies companies for the past 25 years. -

Profiles in Family Philanthropy

Profiles in Family Philanthropy Each month, Family Giving News celebrates the legacies and philanthropic contributions of family philanthropists all over the world by highlighting the story of one philanthropic donor or family in "Profiles in Family Philanthropy." Profiles 2007 MAY/JUNE 2007: The Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies Charles Bronfman returned from a trustees' meeting of the Mount Sinai Medical Center with an idea. Bronfman, Chairman and co-founder with his late wife Andrea of the Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies, had heard of the Medical Center's efforts in the emerging field of personalized medicine. Dr. Jeffrey Solomon, President of the Philanthropies, recalls, “He came back to the foundation and said, ‘Would we do some homework in this arena?’” The result of that homework: a $12.5-million grant to Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York to establish the Charles Bronfman Institute for Personalized Medicine. Called a "leadership gift," the grant aims to support a new approach to medicine which utilizes information about a person's genetic make-up to more effectively detect, treat, and prevent disease. Like many of the Philanthropies' efforts, it represents a significant investment in "the next generation," in this case, the next generation of genetics research and genomics-based medicine. In Memoriam: Andrea Bronfman Andrea Morrison Bronfman, co-chair of The Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies, tragically passed away January 23, 2006 as the result of injuries sustained in a traffic accident. Through her leadership at ACBP and numerous other philanthropic endeavors, she was a shaping force in initiatives aimed at strengthening Jewish identity worldwide, with a focus on Jewish youth, the arts and education. -

Research Guide to Holocaust-Related Holdings at Library and Archives Canada

Research guide to Holocaust-related holdings at Library and Archives Canada August 2013 Library and Archives Canada Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 4 LAC’S MANDATE ..................................................................................................... 5 CONDUCTING RESEARCH AT LAC ............................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE ........................................................................................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE LAC’S ONLINE SEARCH TOOLS ......................................................................................................... 5 LANGUAGE OF MATERIAL.......................................................................................................................................... 6 ACCESS CONDITIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Government of Canada records ................................................................................................................ 7 Private records ................................................................................................................................................ 7 NAZI PERSECUTION OF THE JEWISH BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR............... 7 GOVERNMENT AND PRIME MINISTERIAL RECORDS................................................................................................ -

The Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Family Foundation Yves Savoie

book review Spirited Commitment: The Samuel and Saidye Bronfman Family Foundation The Philanthropist 2011 / volume 24 • 2 by Roderick MacLeod and Eric John Abrahamson Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2010. isbn: 978-0-7735-3710-1 Yves Savoie An acorn illustrates the jacket cover of Spirited Commitment: The Samuel Yves Savoie is Chief Executive and Saidye Bronfman Family Foundation recalling the phrase from a poem by David Officer of the Multiple Sclerosis Everett “Large streams from little fountains flow/Tall oaks from little acorns grown” Society of Canada, 175 Bloor Street East, Suite 700, North Tower, (MacLeod and Abrahamson, 2010, p. 3). The authors note that the oak tree also served Toronto, on m4w 3r8. 1 as the image of CEMP, the business arm of the Bronfman family and of The Samuel and Email: [email protected] . Saidye Bronfman Family Foundation (SSBFF). It is a compelling metaphor both for Sam (Note: The reviewer was Head of Bronfman’s well-documented story of vast wealth built from truly humble beginnings, Development at the Canadian as well as for the less often recounted story of his family foundation that spurred broad- Centre for Architecture from 1990 ranging and multi-generational philanthropy. It is this less-recounted tale which now to 1993.) fills these pages. Spirited Commitment was commissioned by the SSBFF to reflect on its more than fifty years of history. Veteran institutional historian, Eric Abrahamson was commissioned initially as the sole author; he conducted the initial research and completed a first draft. For personal reasons, he could not complete the manuscript. -

Amazon Selling Nazi T-Shirts – Copy

)''/ <J *,' >F EFIK?N<JK KF;8P% Salute to Israel on its 60th Anniversary. C<8J< 8GI C<8J< =FI N<CC <HL@GG<; 8K ! G<I DFEK? *%0 *+/ LG KF +/ DFJ% *0#0'' ;FNE G8PD<EK/#//* 8;ALJK<;8DFLEK*''' Efik_n\jk C\olj n\cZfd\j D`Z_X\c >fc[Y\i^ kf k_\ k\Xd )''/<J*,'*%,C).)_gM-<e^`e\-$jg\\[Jlg\i<c\Zkife`$ 0', +0+$(''' ZXccp :fekifcc\[ KiXejd`jj`fe M\_`Zc\JkXY`c`kp :fekifc KiXZk`fe :fekXZk1 D`Z_X\c >fc[Y\i^ :\cc1 +(- -(.$+)+* nnn%efik_n\jkc\olj%Zfd :fekifc / X`iYX^j Gfn\i X[aljkXYc\ _\Xk\[ c\Xk_\i ]ifek j\Xkj >\e\iXc JXc\j DXeX^\i <dX`c1 d^fc[Y\i^7efik_n\jkc\olj%Zfd DJIG _Xj Y\\e i\[lZ\[ Yp *''' Xe[ `j efn *0#0'' ]fi X e\n C\olj )''/ <J *,'% (#./' ]i\`^_k&G;@# kXo\j# c`Z\ej\# i\^`jkiXk`fe Xe[ `ejliXeZ\ Xi\ \okiX% !C\Xj\ Xe[ ÔeXeZ\ f]]\ij gifm`[\[ k_ifl^_ C\olj =`eXeZ`Xc J\im`Z\j# fe Xggifm\[ Zi\[`k% C\Xj\ \oXdgc\ YXj\[ fe X +/ dfek_ k\id Xk *%0 8GI% Dfek_cp gXpd\ek `j *+/ n`k_ ))/' Hl\\e Jki\\k <Xjk# 9iXdgkfe# FE /#//* [fne gXpd\ek fi \hl`mXc\ek kiX[\ `e# (#./' ]i\`^_k&G;@# ' j\Zli`kp [\gfj`k Xe[ Ôijk dfek_cp gXpd\ek [l\ Xk c\Xj\ `eZ\gk`fe% KXo\j# c`Z\ej\# i\^`jkiXk`fe Xe[ `ejliXeZ\ Xi\ \okiX% -'#''' b`cfd\ki\ XccfnXeZ\2 Z_Xi^\ f] '%)'&bd ]fi \oZ\jj b`cfd\ki\j% Jfd\ Zfe[`k`fej&i\jki`Zk`fej Xggcp%j\ j\\ pfli C\olj [\Xc\i ]fi Zfdgc\k\ [\kX`cj% May 8, 2008 / Iyyar 3, 5768 Publication Mail Agreement #40011766 STEELES MEMORIAL CHAPEL Your Community Chapel since 1927 Congratulations to the S tate of Israel 905-881-6003 Circulation 62,530 Largest Jewish Weekly in Canada www.steeles.org TRIBUNE CALL GETS ‘HITLER’ T-SHIRTS OFF WEB By Wendy B. -

Henryk Grossman Bibliography

Henryk Grossman bibliography Prepared by Rick Kuhn School of Social Science Faculty of Arts Australian National University ACT 0200 Australia 28 June 2006 Contents Preface 2 Material by Henryk Grossman 4 Books and articles 4 Reviews 9 Published correspondence 10 Translations 10 Journals which Grossman edited 10 Archives 10 Interviews and personal communications 13 Photographs 13 General bibliography 15 Rick Kuhn Grossman bibliography Preface This bibliography was prepared by Rick Kuhn in the course of a project that has given rise to the following publications: Henryk Grossman and the recovery of Marxism, University of Illinois Press, Champaign 2007. ‘Introduction to Henryk Grossman’s critique of Franz Borkenau and Max Weber’ Journal of classical sociology 6 (2) July 2006, pp. 195-200. ‘Henryk Grossman and the recovery of Marxism’ Historical materialism 13 (3) 2005, pp. 57- 100 (preprint version http://eprints.anu.edu.au/archive/00002810/01/Henryk_Grossman_and_the_recovery_of _Marxism_preprint.pdf). ‘Economic crisis and socialist revolution: Henryk Grossman’s Law of accumulation, its first critics and his responses’ in Paul Zarembka (ed.) Neoliberalism in crisis, accumulation, and Rosa Luxemburg’s legacy: Research in political economy 21, Elsevir, Amsterdam 2004, pp. 181-221 (preprint version http://eprints.anu.edu.au/archive/00002400/01/Economic_crisis_and_socialist_revolutio n_eprint_secure.pdf). ‘The tradition of Jewish anti-Zionism in the Galician socialist movement’ Australasian Political Studies Association Conference, Canberra, 2-4 October, 2002, http://auspsa.anu.edu.au/proceedings/2002/kuhn.pdf. Revised version http://eprints.anu.edu.au/archive/00002904/01/Tradition_of_Jewish_anti- Zionism_in_the_Galician_socialist_movement.pdf. ‘The Jewish Social Democratic Party of Galicia and the Bund’, in Jack Jacobs (ed.) Jewish politics in Eastern Europe: the Bund at 100 Palgrave/New York University Press, London/New York 2001, pp. -

L1teracy As the Creation of Personal Meaning in the Lives of a Select Group of Hassidic Women in Quebec

WOMEN OF VALOUR: L1TERACY AS THE CREATION OF PERSONAL MEANING IN THE LIVES OF A SELECT GROUP OF HASSIDIC WOMEN IN QUEBEC by Sharyn Weinstein Sepinwall The Department of Integrated Studies in Education A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research , in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education Faculty of Education McGiII University National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 canada Canada Our fie Notre réIérfInœ The author bas granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies ofthis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pemnsslOn. autorisation. 0-612-78770-2 Canada Women of Valour: Literacy as the Creation of Personal Meaning in the Lives of a Select Group of Hassidic Women in Quebec Sharyn Weinstein Sepinwall 11 Acknowledgments One of my colleagues at McGiII in the Faculty of Management was fond of saying "writing a dissertation should change your life." Her own dissertation had been reviewed in the Wall Street Journal and its subsequent acclaim had indeed, 1surmised, changed her life.