Barriers to Voting: Poll Taxes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TTB F 5000.24Sm Excise Tax Return

OMB No. 1513-0083 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY 1. SERIAL NUMBER ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO TAX AND TRADE BUREAU (TTB) EXCISE TAX RETURN (Prepare in duplicate – See instructions below) 3. AMOUNT OF PAYMENT 2. FORM OF PAYMENT $ CHECK MONEY ORDER EFT OTHER (Specify) NOTE: PLEASE MAKE CHECKS OR MONEY ORDERS PAYABLE TO THE ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO TAX AND 4. RETURN COVERS (Check one) BEGINNING TRADE BUREAU (SHOW EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ON ALL CHECKS OR MONEY ORDERS). IF PREPAYMENT PERIOD YOU SEND A CHECK, SEE PAPER CHECK CONVERSION ENDING NOTICE BELOW. 5. DATE PRODUCTS TO BE REMOVED (For Prepayment Returns Only) FOR TTB USE ONLY 6. EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER 7. PLANT, REGISTRY, OR PERMIT NUMBER TAX $ PENALTY 8. NAME AND ADDRESS OF TAXPAYER (Include ZIP Code) INTEREST TOTAL $ EXAMINED BY: DATE EXAMINED: CALCULATION OF TAX DUE (Before making entries on lines 18 – 21, complete Schedules A and B) PRODUCT AMOUNT OF TAX (a) (b) 9. DISTILLED SPIRITS 10. WINE 11. BEER 12. CIGARS 13. CIGARETTES 14. CIGARETTE PAPERS AND/OR CIGARETTE TUBES 15. CHEWING TOBACCO AND/OR SNUFF 16. PIPE TOBACCO AND/OR ROLL-YOUR-OWN TOBACCO 17. TOTAL TAX LIABILITY (Total of lines 9-16) $ 18. ADJUSTMENTS INCREASING AMOUNT DUE (From line 29) 19. GROSS AMOUNT DUE (Line 17 plus line 18) $ 20. ADJUSTMENTS DECREASING AMOUNT DUE (From line 34) 21. AMOUNT TO BE PAID WITH THIS RETURN (Line 19 minus line 20) $ Under penalties of perjury, I declare that I have examined this return (including any accompanying explanations, statements, schedules, and forms) and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct, and includes all transactions and tax liabilities required by law or regulations to be reported. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

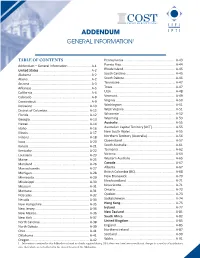

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Download Article (PDF)

5th International Conference on Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation (ICAAT 2016) TAX TRANSPARENCY – AN ANALYSIS OF THE LUXLEAKS FIRMS Johannes Manthey University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Dirk Kiesewetter University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Abstract This paper finds that the firms involved in the Luxembourg Leaks (‘LuxLeaks’) scandal are less transparent measured by the engagement in earnings management, analyst coverage, analyst accuracy, accounting standards and auditor choice. The analysis is based on the LuxLeaks sample and compared to a control group of large multinational companies. The panel dataset covers the years from 2001 to 2015 and comprises 19,109 observations. The LuxLeaks firms appear to engage in higher levels of discretionary earnings management measured by the variability of net income to cash flows from operations and the correlation between cash flows from operations and accruals. The LuxLeaks sample shows a lower analyst coverage, lower willingness to switch to IFRS and a lower Big4 auditor rate. The difference in difference design supports these findings regarding earnings management and the analyst coverage. The analysis concludes that the LuxLeaks firms are less transparent and infers a relation between corporate transparency and the engagement in tax avoidance. The paper aims to establish the relationship between tax avoidance and transparency in order to give guidance for future policy. The research highlights the complex causes and effects of tax management and supports a cost benefit analysis of future tax regulation. Keywords: Tax Avoidance, Transparency, Earnings Management JEL Classification: H20, H25, H26 1. Introduction The Luxembourg Leaks (’LuxLeaks’) scandal made public some of the tax strategies used by multinational companies. -

Ecotaxes: a Comparative Study of India and China

Ecotaxes: A Comparative Study of India and China Rajat Verma ISBN 978-81-7791-209-8 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. ECOTAXES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIA AND CHINA1 Rajat Verma2 Abstract This paper attempts to compare various forms of ecotaxes adopted by India and China in order to reduce their carbon emissions by 2020 and to address other environmental issues. The study contributes to the literature by giving a comprehensive definition of ecotaxes and using it to analyse the status of these taxes in India and China. -

Taxation in Islam

Taxation in Islam The following article is based on the book Funds in the Khilafah State which is a translation of Al-Amwal fi Dowlat Al-Khilafah by Abdul-Qadeem Zalloom.1 Allah (swt) has revealed a comprehensive economic system that details all aspects of economic life including government revenues and taxation. In origin, the permanent sources of revenue for the Bait ul-Mal (State Treasury) should be sufficient to cover the obligatory expenditure of the Islamic State. These revenues that Shar’a (Islamic Law) has defined are: Fa’i, Jizya, Kharaj, Ushur, and income from Public properties. The financial burdens placed on modern states today are far higher than in previous times. When the Caliphate is re-established it will need to finance a huge re-development and industrial programme to reverse centuries of decline, and bring the Muslim world fully into the 21st century. Because of this, the Bait ul-Mal’s permanent sources of revenue may be insufficient to cover all the needs and interests the Caliphate is obliged to spend upon. In such a situation where the Bait ul-Mal’s revenues are insufficient to meet the Caliphate’s budgetary requirements, the Islamic obligation transfers from the Bait ul-Mal to the Muslims as a whole. This is because Allah (swt) has obliged the Muslims to spend on these needs and interests, and their failure to spend on them will lead to the harming of Muslims. Allah (swt) obliged the State and the Ummah to remove any harm from the Muslims. It was related on the authority of Abu Sa’id al-Khudri, (ra), that the Messenger of Allah (saw) said: “It is not allowed to do harm nor to allow being harmed.” [Ibn Majah, Al-Daraqutni] Therefore, Allah (swt) has obliged the State to collect money from the Muslims in order to cover its obligatory expenditure. -

Mass Taxation and State-Society Relations in East Africa

Chapter 5. Mass taxation and state-society relations in East Africa Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Ole Therkildsen* Chapter 5 (pp. 114 – 134) in Deborah Braütigam, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad & Mick Moore eds. (2008). Taxation and state building in developing countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.cambridge.org/no/academic/subjects/politics-international-relations/comparative- politics/taxation-and-state-building-developing-countries-capacity-and-consent?format=HB Introduction In East Africa, as in many other agrarian societies in the recent past, most people experience direct taxation mainly in the form of poll taxes levied by local governments. Poll taxes vary in detail, but characteristically are levied on every adult male at the same rate, with little or no adjustment for differences in individual incomes or circumstances. In East Africa and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, poll taxes have been the dominant source of revenue for local governments, although their financial importance has tended to diminish over time. They have their origins in the colonial era, where at first they were effectively an alternative to forced labour. Poll taxes have been a source of tension and conflict between state authorities and rural people from the colonial period until today, and a catalyst for many rural rebellions. This chapter has two main purposes. The first, pursued through a history of poll taxes in Tanzania and Uganda, is to explain how they have affected state-society relations and why it has taken so long to abolish them. The broad point here is that, insofar as poll taxes have contributed to democratisation, this is not through revenue bargaining, in which the state provides representation for taxpayers in exchange for tax revenues (Levi 1988; Tilly 1990; Moore 1998; and Moore in this volume). -

Pastor's Leadership in Tithing Has Paid Dividends

Lower Susquehanna Synod news Pastor’s leadership in tithing has paid dividends When St. Paul Lutheran, York, interviewed the Rev. Stan Reep as a potential pastor, they asked how he’d advise the church to use its $3.6 million of inherited wealth. He said the first step is to tithe it—give away 10 percent. “And everybody looked at me like I had three heads,” said Reep, who explained that he and his wife, Emily, believed strongly in tithing and practiced it faithfully. “I said, well, it’s the same theology. If you want the congregation to do this, if you want the members to do this, you have to lead by doing it.” When Reep was called as pastor there in 2004, he followed through. St. Paul gave away $360,000 and made it a policy to tithe all future gift income. “In the 12 years I’ve been there, I think we’ve given away $1 million,” he said. “There’s a loaves and fishes crazy, crazy situation!” Tithing isn’t only the policy for new bequests, but The Rev. Stan Reep (left) talks Bible with Tony Culp. also an undercurrent of St. Paul’s annual cam- paigns, where people are subtly invited to consider the importance of generosity and also the faithful tithing. St. Paul also recently held a “Try a Tithe stewarding of the resources entrusted to us.” Sunday,” where members were asked, just for that Sunday, to donate 10 percent of their weekly In addition to asking people about their giving, income. The offering was about $6,300, compared the annual stewardship campaign invites people to the usual $4,000. -

EP Reaction to the Lux-Leaks Revelations

At a glance Ask EP - EP Answers EP reaction to the Lux-leaks revelations Many citizens are writing to the European Parliament wishing to know what the Parliament is doing on the issue of the 'Lux-leaks' revelations concerning advance tax rulings granted to multinationals in Luxembourg. ©European Parliament The European Parliament has, for many years, pushed for on an effective fight against tax fraud, tax evasion and tax havens. That's why the Parliament takes very seriously the revelations concerning advance tax rulings for multinationals in Luxembourg and has reacted promptly and strongly. Immediately after the 'Lux-leaks' revelations, the European Parliament held an extraordinary debate on the fight against tax evasion in which the President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker also participated. The statement by the President of the Commission and the recording of the debate are available online on the website of the European Parliament. During the debate, MEPs called for tax harmonisation and transparency on national tax rulings. A European Parliament press release of 12 November 2014 summarises the discussion between President Jean-Claude Juncker and the Chairs of the political groups. Motion of censure rejected In response to the plenary debate on the 'Lux leaks', a number of MEPs tabled a motion of censure on the European Commission that was debated on 24 November 2014 and put to a vote on 27 November 2014. A vast majority of the European Parliament rejected the motion of censure (461 votes against, 101 in favour and 88 abstentions), expressing support for the European Commission. The mandate of the special committee In order to look into tax ruling practices in the Member States, a number of Members of the European Parliament requested the setting up of a committee of inquiry. -

Sustainable Public Finance: Double Neutrality Instead of Double Dividend

Journal of Environmental Protection, 2016, 7, 145-159 Published Online February 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2016.72013 Sustainable Public Finance: Double Neutrality Instead of Double Dividend Dirk Loehr Trier University of Applied Sciences, Environmental Campus Birkenfeld, Birkenfeld, Germany Received 27 November 2015; accepted 31 January 2016; published 4 February 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract A common answer to the financial challenges of green transformation and the shortcomings of the current taxation system is the “double dividend approach”. Environmental taxes should either feed the public purse in order to remove other distorting taxes, or directly contribute to financing green transformation. Germany adopted the former approach. However, this article argues, by using the example of Germany, that “good taxes” in terms of public finance should be neutral in terms of environmental protection and vice versa. Neutral taxation in terms of environmental im- pacts can be best achieved by applying the “Henry George principle”. Additionally, neutral taxation in terms of public finance is best achieved if the revenues from environmental taxes are redistri- buted to the citizens as an ecological basic income. Thus, distortive effects of environmental charges in terms of distribution and political decision-making might be removed. However, such a financial framework could be introduced step by step, starting with a tax shift. Keywords Double Dividend, Double Neutrality, Tinbergen Rule, Henry George Principle, Ecological Basic Income 1. -

Bulletin No. 13 (Motor Vehicle Excise Tax & Personal Property Tax)

MAINE REVENUE SERVICES PROPERTY TAX DIVISION PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NO. 13 MOTOR VEHICLE EXCISE TAX & PERSONAL PROPERTY TAX REFERENCE: 36 M.R.S. §§ 1481 through 1491 December 9, 2019; replaces November 21, 2017 revision 1. General The motor vehicle excise tax is an annual tax imposed for the privilege of operating a motor vehicle on public roads. This bulletin discusses the applicability of motor vehicle excise tax to automobiles, buses, trucks, truck tractors, motorcycles, and special mobile equipment. Mobile homes, camper trailers, and aircraft are also subject to excise tax, but are not covered by this bulletin. Detailed information about the excise tax as applied to mobile homes and camper trailers may be found in Property Tax Bulletin No. 6 – Taxation of Mobile Homes and Camper Trailers. For information about the excise tax as applied to aircraft, contact the Property Tax Division using the contact information at the end of this bulletin. As a rule, a registered motor vehicle owned by a person on April 1 and on which an excise tax was paid is exempt from property taxes. A motor vehicle, for which an excise tax has not been paid before property taxes are committed is subject to property tax. The Secretary of State provides municipal excise tax collectors with standard vehicle registration forms for the collection of excise tax. 2. The Motor Vehicle Excise Tax A. When applicable. The excise tax on motor vehicles applies where the owner of the motor vehicle intends to use it on public roads during the year. B. Where excise tax is payable. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide.