Drawing Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCF Peach Pit 2019

Join us in our wooded setting, 13 miles west of Eugene, The Oregon Country Fair near Veneta, Oregon, for an unforgettable adventure. Three magical days from 11:00 to 7:00. Get Social: fli guide to entertainment Download as PDF: OregonCountryFair.org/PeachPit Peach Pit and the Country Fair site Join us in our wooded setting, 13 miles west of Eugene, The Oregon Country Fair near Veneta, Oregon, for an unforgettable adventure. Three magical days from 11:00 to 7:00. Get Social: fli guide to entertainment Download as PDF: OregonCountryFair.org/PeachPit Peach Pit and the Country Fair site Join us in our wooded setting, 13 miles west of Eugene, The Oregon Country Fair near Veneta, Oregon, for an unforgettable adventure. Three magical days from 11:00 to 7:00. Get Social: fli guide to entertainment Download as PDF: OregonCountryFair.org/PeachPit Peach Pit and the Country Fair site Happy Birthday Oregon Country Fair! Year-Round Craft Demonstrations Fair Roots Lane County History Museum will be featuring the Every day from 11:00 to 7:00 at Black Oak Pocket Park Leading the Way, a new display, gives a brief overview first 50 years of the Fair in a year-long exhibit. The (across from the Ritz Sauna) craft-making will be of the social and political issues of the 60s that the exhibit will be up through June 6, 2020—go check demonstrated. Creating space for artisans and chefs Fair grew out of and highlights areas of the Fair still out a slice of Oregon history. OCF Archives will also to sell their creations has always been a foundational reflects these ideals. -

Oriental Medicine Doctoral Programs

SPRING 2017 www.pacificcollege.edu A Brief History of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine Doctoral Programs doctorate in acupuncture and Oriental medicine has been a goal of the profession since its beginnings in the late 1970s. A At that time, however, the maturity of the educational institu- tions and the regulatory environment made it a goal with only a dis- tant completion date. Throughout the 1990s, the colleges continually increased their expertise and resources and the doctoral project gath- ered momentum. Finally, by May 2000, standards for the post-graduate doctorate, the Doctor of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (DAOM), were approved by the Accreditation Commission of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (ACAOM). Entrance to the DAOM required a mas- ter’s degree in acupuncture and Oriental medicine. continued on page 4 The 5 Phases of Event Training INSIDE THIS ISSUE.... PAID PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. POSTAGE Bolingbrook, IL PERMIT NO.932 Using Sports Acupuncture 3 Teaching is a Healing Art 4 TCM for Diabetes Mellitus Insights of a TCM Dermatologist By ERIN HURME, DAOM 10 10 Citrus and Pinellia: Loyalty, Simplicity and Integrity hen treating athletes, to ensure the treatments hold and 11 Table Thai Massage vs. Floor there are many things to the athlete can maintain their per- Thai Massage: You’re Asking W take into consideration formance and reach their goals. Ath- the Wrong Question and timing is one of the most critical. letes tend to reinjure their body in 12 Yin and Yang Most athletes participate in scheduled the same location again and again. events that they prepare for months This can vary slightly depending on 14 Herbal Treatment in Special in advance. -

EXPOSE YOURSELF to ART Towards a Critical Epistemology of Embarrassment

EXPOSE YOURSELF TO ART Towards a Critical Epistemology of Embarrassment Gwyneth Siobhan Jones Goldsmiths University of London PhD Thesis 2013 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Gwyneth Siobhan Jones 2 ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the negative affect of ‘spectatorial embarrassment’, a feeling of exposure and discomfort sometimes experienced when looking at art. Two particular characteristics of embarrassment figure in the methodology and the outcome of this enquiry; firstly that embarrassment is marginal, of little orthodox value, and secondly, it is a personal experience of aversive self-consciousness. The experiential nature of embarrassment has been adopted throughout as a methodology and the embarrassments analysed are, for the most part, my own and based on ‘true’ experience. Precedent for this is drawn from ‘anecdotal theory’, which uses event and occasion in the origination of a counter-theory that values minor narratives of personal experience in place of the generalising and abstract tendencies of theory-proper. The context is a series of encounters with artworks by Gilbert & George, Jemima Stehli, Franko B, Adrian Howells, and Sarah Lucas. They are connected by their contemporaneity, their ‘British-ness’, and that they allow the spectator no comfortable position to look from. This enquiry engages with theories of ‘the gaze’ (as both aesthetic disinterest and a dubious sign of cultural competence) and the challenge to aesthetic disinterest made by ‘transgressive art’ which may provoke a more engaged, even embodied response. Each encounter sparks consideration of differing causes and outcomes of embarrassment that resonate beyond art to broader sociocultural territories particularly in terms of gender and class. -

PSCS Chapter 8

Planescape Campaign Setting And beyond… Chapter 8: And Beyond Project Managers Sarah Hood Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Andy Click Writers Christopher Smith Adair Richard Adams Jeffery Scott Nutall Sarah Hood Todd Wes Stewart Christopher Campbell Gabriel Sorrel Dayna Nichols Mitra Salehi galzionntl Janus Aran Layout Sarah Hood 1 And Beyond… And beyond… Outside of Sigil the next biggest thing you need to learn ‗bout is the Planes. They‘re infinite, so‘s it‘s not like you can learn everything in one shot. But we‘ll try our best, hm? Sigil is said to be the center of the multiverse, the center of all. From Sigil one can affect the Planes entire. Or some such drek. Now, since Sigil is the center of things, the going theory is that as a ‗fulcrum point‘ (see? You too can learn a thing or two from a Guvner), if one were to nudge Sigil one way or the other in belief, then the rest of the Planes would follow, like a snowball at the top of a mountain making for an avalanche. No one‘s gotten a strong enough grip on the city though to test that theory out yet, and I‘m rather glad for that myself. Now let‘s take a look at why so many cutters believe such bunk. The planes, such as they are, exist as a representation of a meaning or element or aspect of reality. Confusin‘ enough for ya? I‘m not yet done. The planes themselves are generally infinite. They exist ‗beside‘, ‗between‘ or ‗concurrent‘ to each other only by our own convention—it is not so simple just to walk around in one plane and mark a point on your map where the other begins - though I‘m sure some lucky berk out there will prove me wrong tomorrow. -

Page 1 ULTIMA K O N S E R T E R S C E N E K U N S T O P E R a in S T

SEMINARER INSTALLASJONER DANS OPERA KONSERTER BARNEARRANGEMENTER SCENEKUNST KOMPONISTMØTER ULTIMA InnhoLd/conTenTs JO MICHAEL STEIN HENRICHSEN TO BrITISK LYd ................................................................................... 58 Bli en døråpner! ....................................................................................... 4 FO Become a door opener! ....................................................................... 6 HILD BORCHGREVINK Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises ........................................... 58 GEIR JOHNSON Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises ........................................... 59 Ultima 2007: I ukjent land ...................................................................7 Ultima 2007: In unknown lands .......................................................11 ANDERS FØRISDAL Fra Beckett til doku-såper ................................................................. 60 From Beckett to a documentary soap .......................................... 63 UnIke kvInnesTemmer .................................................................14 IAN PACE HILD BORCHGREVINK Tradisjon og nytenkning. Et personlig tilsvar til Dillons En japansk vulkan..................................................................................16 The Book of Elements ..........................................................................66 A Japanese Power Station ................................................................. 21 Tradition and invention. A personal response to Dillon’s -

Chi Nei Tsang Internal Organs Chi Massage.Pdf

- 1 - Chi Nei Tsang I Internal Organs Chi Massage Mantak Chia Edited by: Valerie Meszaros and David Flatley - 2 - Editor: Judith Stein Contributing Writers: Chuck Soupios, Michael Winn, Mackenzie Stewart, Valerie Meszaros Illustrator: Juan Li Cartoonist: Don Wilson Cover Illustrator: Ivan Salgado Graphics: Max Chia Revised Design and Production: Saniem Chaisarn, Siriporn Chaimongkol Revised Editing: Jean Chilton Copyright © 1993 Mantak and Maneewan Chia Universal Tao Publications 274/1 Moo 7, Luang Nua, Doi Saket, Chiang Mai, 50220 Thailand Fax (66) (53) 495-853 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.universal-tao.com ISBN: 0-935621-46-6 Manufactured in Thailand Ninth Printing, 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission from the author except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. - 3 - Dedicated to Healers Everywhere - 4 - Contents Contents.................................................................................... i About the Author ...................................................................... xv Acknowledgements ................................................................. xix Words of Caution..................................................................... xxi Introduction What is Chi Nei Tsang ?...................................................... 1 A. Causes of Sickness: Organ Obstructions and Congestion in the Abdomen ...................................... 1 B. Chi Nei Tsang: -

Årsmelding Nasjonalmuseet 2008 Årsmelding Nasjonalmuseet 2008

ÅRSMELDING NASJONALMUSEET 2008 ÅRSMELDING NASJONALMUSEET 2008 2 Innhold Ansvarlig redaktør: Audun Eckhoff 1 Styrets årsberetning 2008 Side 5 Redaktør: Anita Rebolledo 2 Direktørens stab 10 Redaksjonskomité: Françoise Hanssen-Bauer, Anne Qvale, Frode Haverkamp, Stein Simensen, Toril Fjelde Høye, 3 Nasjonalmuseets byggeprosjekter 11 Else-Marit Laskerud og Birgitte Sauge 4 Forskning og utvikling 13 Design: Kristoffer Busch 5 Landsdekkende program 19 Redaksjonen avsluttet 12. august 2009 6 Utstillings- og formidlingsvirksomheten 22 En utvidet utgave av Nasjonalmuseets årsmelding 7 Bak fasaden: revisjon av samlingene 32 2008 er tilgjengelig på museets nettsider 8 Avdeling samling og utstilling 35 www.nasjonalmuseet.no. Denne versjonen har også lister over museets utlån og museets ansatte. 9 Nyervervelser i 2008 37 10 Avdeling formidling 46 Omslag: 11 Avdeling museumstjenester 54 Interiørbilde fra Ulltveit-Moe paviljongen. Nasjonalmuseet – Arkitektur åpnet 6. mars i 2008, og er Nasjonalmuseets første nybygg. Det er arkitekt Sverre Fehn som har tegnet 12 Nettverk og styreverv 59 ombyggingen og Ulltveit-Moe paviljongen. Utgangspunktet var Norges Banks første 13 Avdeling drift og sikkerhet 60 bygning i Christiania, tegnet av Christian Heinrich Grosch. 14 Avdeling administrasjon 61 Foto: Morten Thorkildsen, Nasjonalmuseet 15 Arbeidsmiljø 63 Omslag innside: 16 Avdeling økonomi og regnskap 64 Interiørbilder fra det nyrestaurerte Nasjonalmuseet – Arkitektur. 17 Årsregnskap for stiftelsen Foto: Morten Thorkildsen, Nasjonalmuseet Nasjonalmuseet for kunst 2008 65 18 Utlån 2008 76 19 Ansatte i Nasjonalmuseet pr 31.12.2008 83 1 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2008 asjonalmuseet for kunst, Samlede omvisninger i 2007 var LANDSDEKKENDE PROGRAM: arkitektur og design er et 1565. Det har altså vært en økning UTSTILLINGER, FORMIDLING N museum for hele Norge som på 161 fra i fjor. -

Crafting Words and Wood: Myth, Carving and Húsdrápa

Crafting Words and Wood: Myth, Carving and Húsdrápa By Erik Schjeide A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John Lindow, Chair Professor Jonas Wellendorf Professor Beate Fricke Fall 2015 Abstract Crafting Words and Wood: Myth, Carving and Húsdrápa by Erik Schjeide Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor John Lindow, Chair In the poem Húsdrápa, ca. 985, Úlfr Uggason described woodcarvings of mythological scenes adorning an Icelandic hall owned by the chieftain Óláfr pái. The performance, of which some verses have been passed down in writing, was an act of referential intermedia, insofar as the art form of skaldic poetry presented with woven words the content of a wood-carved medium that has long since rotted away. Hence, the composition of the poem combined with the carvings created a link that opens up a union between extant literary sources and material culture which contributes to expanding cultural insight. This study draws from a range of sources in order to answer central research questions regarding the appearance and qualities of the missing woodcarvings. Intermedia becomes interdisciplinary in the quest, as archaeological finds of Viking Age and early medieval woodcarvings and iconography help fill the void of otherwise missing artifacts. Old Norse literature provides clues to the mythic cultural values imbued in the wooden iconography. Anthropological and other theories drawn from the liberal arts also apply as legend, myth and art combine to inform cultural meaning. -

The Hudson Valley in Historic Postcards

RIVER OF DREAMS Hudson Valley Heritage Robert F. Jones, series editor 1. Robert O. Binnewies, Palisades: 100,000 Acres in 100 Years. 2. Brian J. Cudahy, Rails Under the Mighty Hudson: The Story of the Hudson Tubes, the Pennsylvania Tunnels, and Manhattan Transfer. 3. Jason K. Duncan, Citizens or Papists? The Politics of Anti-Catholicism in New York, 1685–1821. 4. Roger Panetta, Westchester: The American Suburb. RIVER OF DREAMS The Hudson Valley in Historic Postcards George J. Lankevich Fordham University Press New York 2006 Copyright © 2006 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other- except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lankevich, George J., 1939– River of dreams: the Hudson Valley in historic postcards / George J. Lankevich.—1st ed. p.cm.—(Hudson Valley heritage ; 5) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2579-8 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2579-8 (alk. paper) 1. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. and N.J.)—History. 2. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. and N.J.)—His- tory—Pictorial works. 3. Postcards—Hudson River Valley (N.Y. and N.J.) 4. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. and N.J.)—History, Local. I. Title. F127.H8L36 2006 974.7’3—dc22 2006021328 Printed in the United States of America 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 First edition. -

Trademarks and Service Marks Registered with the South Carolina Secretary of State List Updated on Friday, October 1, 2021

Trademarks and Service Marks Registered with the South Carolina Secretary of State List Updated on Friday, October 1, 2021 Trademark/Service Mark Name Mark Type Goods Or Services Class Applicant Name Expiration Number Date "A Medicare Moment" ServiceMark Insurance Medicare 2 SHK & Associates, Inc. 09/25/2024 supplements, Medicare Advantage plans, prescription drug plans, etc. "A SWEET SHIMMER TO YOUR TASTE BUDS" ServiceMark A confections company. 1 Whitt's Berries, LLC 02/26/2026 in pink "All in the Approach" Trademark Clothing; shirts, 25 Birddog Apparel, LLC 10/11/2025 windbreakers, shorts, hats/apparel "Come Fish With Me" ServiceMark Charter fishing. 8 WTV Inland Charters LLC 11/30/2023 "Front Porch of the Lowcountry" ServiceMark General advertising 1, 4, 7, 8 City of Walterboro 04/18/2024 purposes to boost tourism for the City of Walterboro. "If the Truth be Told" ServiceMark Stage performance. 7 Patrice Hawthorne 10/05/2022 "Make America...America!!" Trademark Clothing, head covers 25, 26 Charles Adams 04/24/2024 (hats/caps). "Relax...we'll manage" ServiceMark Property management. 1 Myrtle Beach Management, LLC 03/05/2025 "Service 2nd to None" ServiceMark Pest control services. 3 Economy Exterminators, Inc. 05/30/2024 "The Biggest Little Store in S.C." ServiceMark Hardware store. 1 Horse and Garden Ace Hardware 12/20/2021 "The Hands-On Car Care Professionals" ServiceMark Car wash and full detailing 8 F1 Investments, LLC 03/20/2022 services including RVs, boats and motorcycles. #Beautiful Mind Beautiful Lady Trademark Clothing, shirts and cards 16, 25 Virtues Enterprises LLC 03/24/2026 sold at motivational speaking events. -

(Pdf) Download

DECODING THE DELUGE AND FINDING THE PATH FOR CIVILIZATION Volume II Of Three Volumes by David Huttner Version 25.4; Release date: March 7, 2020 Cover by A. Watson, Chen W. and D. Huttner Copyright 2020, By David Robert Huttner I hereby donate this digital version of this book to the public domain. You may copy and distribute it, provided you don’t do so for profit or make a version using other media (e.g. a printed or cinematic version). For anyone other than me to sell this book at a profit is to commit the tort of wrongful enrichment, to violate my rights and the rights of whomever it is sold to. I also welcome translations of the work into other languages and will authorize the translations of translators who are competent and willing to donate digital versions. Please email your feedback to me, David Huttner, at [email protected]. Other Works of David Huttner, soon to be Available Autographed and in Hardcopy at http://www,DavidHuttnerBooks.com , Include: Decoding the Deluge and finding the path for civilization, vols 1&3 Irish Mythology passageway to prehistory Stage II of the Nonviolent Rainbow Revolution Making the Subjective and Objective Worlds One Just Say No to Latent Homosexual Crusades Social Harmony as Measured by Music (a lecture) The First Christmas (a short play) The Spy I Loved secrets to the rise of the Peoples Republic of China Selected Works of David Huttner Volumes 1 and 2 Heaven Sent Converting the World to English TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS VOLUME 2 21. -

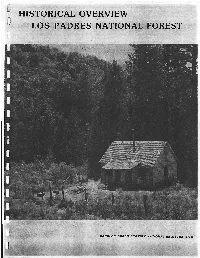

Historical Overview of the Los Padres National Forest

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF LOS PADRES NATIONAL FOREST E. R. (JIM) BLAKLEY Naturalist and Historian of the Santa Earbara Eackcountry and KAREN BARNETTE Cultural Resources Specialist Los Padres National Forest July 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 .0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and Objectives .................................... 1 1.2 Methods ............. ....................................... 2 1.3 Organization of the Overview .............................. 2 2.0 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW 2.1 Introduction .............................................. 4 2.2 Hispanic Period 2.2.1 Early Spanish Explorations ........................ 4 2.2.2 The Missions and the Spanish Colonial Government . Missionization .................................. 8 . Timber Harvesting During the Spanish Period ..... 12 . Spanish Land Grants: the Ortega Concession ..... 13 . mpeditions to the Interior ..................... 14 2.2.3 Mexican Period . Mission Indian Rebellions and Mexican Expeditions to the Interior ..................... 16 . Mexican Land Grants and Secularization .......... 21 2.3 Early American Period ..................................... 28 2.3.1 Conquest' Years .................................... 28 2.3.2 Homestead Period .................................. 35 . Southern Monterey County Coast .................. 35 . Monterey County Interior ........................ 36 . San Luis Obispo County, Lopez Canyon and the Upper Cuyama .................................... 36 . Sisquoc River Valley ............................ 37 . Other Santa Barbara County Fiomesteads