Historical Overview of the Los Padres National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

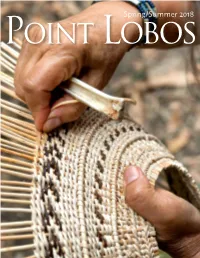

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Building 27, Suite 3 Fort Missoula Road Missoula, MT 59804

Photo by Louis Kamler. www.nationalforests.org Building 27, Suite 3 Fort Missoula Road Missoula, MT 59804 Printed on recycled paper 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Island Lake, Eldorado National Forest Desolation Wilderness. Photo by Adam Braziel. 1 We are pleased to present the National Forest Foundation’s (NFF) Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2013. During this fourth year of the Treasured Landscapes campaign, we have reached $86 million in both public and private support towards our $100 million campaign goal. In this year’s report, you can read about the National Forests comprising the centerpieces of our work. While these landscapes merit special attention, they are really emblematic of the entire National Forest System consisting of 155 National Forests and 20 National Grasslands. he historical context for these diverse and beautiful Working to protect all of these treasured landscapes, landscapes is truly inspirational. The century-old to ensure that they are maintained to provide renewable vision to put forests in a public trust to secure their resources and high quality recreation experiences, is National Forest Foundation 2013 Annual Report values for the future was an effort so bold in the late at the core of the NFF’s mission. Adding value to the 1800’s and early 1900’s that today it seems almost mission of our principal partner, the Forest Service, is impossible to imagine. While vestiges of past resistance what motivates and challenges the NFF Board and staff. to the public lands concept live on in the present, Connecting people and places reflects our organizational the American public today overwhelmingly supports values and gives us a sense of pride in telling the NFF maintaining these lands and waters in public ownership story of success to those who generously support for the benefit of all. -

Attachment E Part 2

Response to Correspondence from Arroyos & Foothills Conservancy Regarding the ArtCenter Master Plan Note that the emails (Attachment A) dated after April 25, 2018, were provided to the City after the end of the CEQA comment period, and, therefore, the emails and the responses below are not included in the EIR, and no response is required under CEQA. However, for sake of complete analysis and consideration of all comments submitted, the City responds herein and this document is made part of the project staff report. Response to Correspondence This correspondence with the Arroyos & Foothills Conservancy occurred in the context of the preparation of the EIR for the ArtCenter Master Plan. The formal comment letter from Arroyos & Foothills Conservancy included in this correspondence was responded to as Letter No. 6 in Section III, Response to Comments, of the April 2018 Final EIR for the ArtCenter Master Plan. The primary correspondence herein is comprised of emails between John Howell and Mickey Long discussing whether there is a wildlife corridor within the Hillside Campus, as well as emails between John Howell and CDFW regarding whether there is a wildlife corridor and whether CDFW will provide a comment letter regarding the ArtCenter Project for the Planning Commission hearing on May 9, 2018. Note that CDFW submitted a comment letter on May 9, 2018, after completion of the Draft EIR and Final EIR. The City has also provided a separate response to this late comment letter. This correspondence centers around the potential for the Hillside Campus to contribute to a wildlife corridor. The CDFW was contacted during preparation of the Final EIR to obtain specific mapping information to provide a more comprehensive description of the potential for wildlife movement within the Hillside Campus within the Final EIR. -

Grooming Veterinary Pet Guidelines Doggie Dining

PET GUIDELINES GROOMING VETERINARY We welcome you and your furry companions to Ventana Big Sur! In an effort to ensure the peace and tranquility of all guests, we ask for your PET FOOD EXPRESS MONTEREY PENINSULA assistance with the following: 204 Mid Valley Shopping VETERINARY EMERGENCY & Carmel, CA SPECIALTY CENTER A non-refundable, $150 one-time fee per pet 831-622-9999 20 Lower Ragsdale Drive will be charged to your guestroom/suite. Do-it-yourself pet wash Suite 150 Monterey, CA Pets must be leashed at all times while on property. 831.373.7374 24 hours, weekends and holidays Pets are restricted from the following areas: Pool or pool areas The Sur House dining room Spa Alila Organic garden Owners must be present, or the pet removed from the room, for housekeeping to freshen your guestroom/suite. If necessary, owners will be required to interrupt activities to attend to a barking dog that may be disrupting other guests. Our concierge is happy to help you arrange pet sitting through a local vendor (see back page) if desired. These guidelines are per county health codes; the only exceptions are for certified guide dogs. DOGGIE DINING We want all of our guests to have unforgettable dining experiences at Ventana—so we created gourmet meals for our furry friends, too! Available 7 a.m. to 10 p.m through In Room Dining or at Sur House. Chicken & Rice $12 Organic Chicken Breast / Fresh Garden Vegetables / Basmati Rice Coco Patty $12 Naturally Raised Ground Beef / Potato / Garden Vegetables Salmon Bowl $14 Salmon / Basmati Rice / Sweet Potato -

Santa Maria Project

MP Region Public Affairs, 916-978-5100, http://www.usbr.gov/mp, February 2016 Mid-Pacific Region, Santa Maria Project Construction individual landholders pump water according to The Santa Maria Project, authorized in 1954, is their needs. The objective of the project as located in California about 150 miles northwest authorized is to release regulated water from of Los Angeles. A joint water conservation and storage as quickly as it can be percolated into flood control project, it consists of the the Santa Maria Valley ground-water basin. Twitchell Dam where construction began in With this type of operation, Twitchell July 1956 and was completed in October Reservoir is empty much of the time. For this 1958.The Reservoir was constructed by the reason, recreation and fishing facilities are not Bureau of Reclamation, and a system of river included in the project. levees was constructed by the Corps of Engineers. Twitchell Dam Twitchell Dam is located on the Cuyama River about 6 miles upstream from its junction with the Sisquoc River. The dam regulates flows along the lower reaches of the river and impounds surplus flows for release in the dry months to help recharge the ground-water basin underlying the Santa Maria Valley, thus minimizing discharge of water to the sea at Guadalupe. The dam is an earthen fill structure having a height of 241 feet with 216 feet above streambed, and a crest length of 1,804 feet. The dam contains approximately 5,833,000 yards of Twitchell Dam and Reservoir material. The multi-purpose Twitchell Reservoir Water Supply has a total capacity of 224,300 acre-feet. -

Historic P U B Lic W Ork S P Roje Cts on the Ce N Tra L

SHTOIRICHISTORIC SHTOIRIC P U B LIC W ORK S P ROJE TSCP ROJE CTS P ROJE TSC ON THE CE N TRA L OCA STCOA ST OCA ST Compiled by Douglas Pike, P.E. Printing Contributed by: Table of Contents Significant Transportation P rojects......2 El Camino Real................................................... 2 US Route 101...................................................... 3 California State Route 1...................................... 6 The Stone Arch Bridge ..................................... 11 Cold Spring Canyon Arch Bridge..................... 12 Significant W ater P rojects...................14 First Dams and Reservoirs................................ 14 First Water Company........................................ 14 Cold Spring Tunnel........................................... 15 Mission Tunnel ................................................. 16 Gibraltar Dam ................................................... 16 Central Coast Conduit....................................... 18 Water Reclamation In Santa Maria Valley....... 23 Twitchell Dam & Reservoir.............................. 24 Santa Maria Levee ............................................ 26 Nacimiento Water Project................................. 28 M iscellaneous P rojects of Interest.......30 Avila Pier .......................................................... 30 Stearns Wharf.................................................... 32 San Luis Obispo (Port Harford) Lighthouse..... 34 Point Conception Lighthouse............................ 35 Piedras Blancas Light ...................................... -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

4. Environmental Impact Analysis 4. Cultural Resources

4. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS 4. CULTURAL RESOURCES 4.4.1 INTRODUCTION The following section addresses the proposed Project’s potential to result in significant impacts upon cultural resources, including archaeological, paleontological and historic resources. On September 20, 2013, the South Central Coastal Information Center (SCCIC) and the Vertebrate Paleontology Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County were contacted to conduct a records search for cultural resources within the Project Site at the intersection of Lyons Avenue and Railroad Avenue and extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University and northwest towards the intersection of 12th Street and Arch Street and immediate Project vicinity. The analysis presented below is based on the record search results provided from the SCCIC, dated October 2, 2013, and written correspondence from The Vertebrate Paleontology Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, dated October 18, 2013. Correspondences from both agencies are included in Appendix E to this Draft EIR. 4.4.2 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING Description of the Study Area The Project Site is located at the intersection of Lyons Avenue and Railroad Avenue and extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University and northwest towards the intersection of 12th Street and Arch Street. The Project Site also includes the closure of an at- grade crossing at the intersection of Railroad Avenue and 13th Street. The portion of the Project Site that extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University is located in an area of primarily undeveloped land within the city limits of Santa Clarita. -

National Forest Imagery Catalog Collection at the USDA

National Forest Imagery Catalog collection at the USDA - Farm Service Agency Aerial Photography Field Office (APFO) 2222 West 2300 South Salt Lake City, UT 84119-2020 (801) 844-2922 - Customer Service Section (801) 956-3653 - Fax (801) 956-3654 - TDD [email protected] http://www.apfo.usda.gov This catalog listing shows the various photographic coverages used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and archived at the Aerial Photography Field Office. This catalog references U.S. Forest Service (FS) and other agencies imagery. For imagery prior to 1955, please contact the National Archives & Records Administration: Cartographic & Architectural Reference (NWCS-Cartographic) Aerial Photographs Team http://www.archives.gov/research/order/maps.html#contact Coverage of U.S. Forest Service photography is listed alphabetically for each forest within a region. Numeric and alpha codes used to identify FS projects are determined by the Forest Service. The original film type for most of this imagery is a natural color negative. Line indexes are available for most projects. The number of index sheets required to cover a project area is shown on the listing. Please reference the remarks column, which may identify a larger or smaller project area than the National Forest area defined in the header. Offered in the catalog listing at each National Forest heading is a link to locate the Regional and National Forest office address and phone number at: http://www.fs.fed.us/intro/directory You may wish to visit the National Forest office to view the current imagery and have them assist you in identifying aerial imagery from the APFO. -

Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area

Crashing waves, redwoods and historic sites Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area Some of the most beautiful sights in California can be found in Monterey area California State Parks. Rocky cliffs, crashing waves, redwood trees, and historic sites are within an easy drive of each other. "When you look at the diversity of state parks within the Monterey District area, you begin to realize that there is something for everyone - recreational activities, scenic beauty, natural and cultural history sites, and educational programs,” said Dave Schaechtele, State Parks Monterey District Public Information Officer. “There are great places to have fun with families and friends, and peaceful and inspirational settings that are sure to bring out the poet, writer, photographer, or artist in you. Some people return to their favorite state parks, year-after-year, while others venture out and discover some new and wonderful places that are then added to their 'favorites' list." State Parks in the area include: Limekiln State Park, 54 miles south of Carmel off Highway One and two miles south of the town of Lucia, features vistas of the Big Sur coast, redwoods, and the remains of historic limekilns. The Rockland Lime and Lumber Company built these rock and steel furnaces in 1887 to cook the limestone mined from the canyon walls. The 711-acre park allows visitors an opportunity to enjoy the atmosphere of Big Sur’s southern coast. The park has the only safe access to the shoreline along this section of cast. For reservations at the park’s 36 campsites, call ReserveAmerica at (800) 444- PARK (7275). -

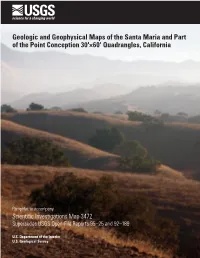

Geologic and Geophysical Maps of the Santa Maria and Part of the Point Conception 30'×60' Quadrangles, California

Geologic and Geophysical Maps of the Santa Maria and Part of the Point Conception 30'×60' Quadrangles, California Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3472 Supersedes USGS Open-File Reports 95–25 and 92–189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Looking northwest from near Zaca Creek to Zaca Ridge on the east edge of the map area (see pamphlet figure 2 for location of Zaca Creek and Zaca Ridge). Hills in foreground are underlain by gently dipping early Pleistocene and upper Pliocene Paso Robles Formation locally overlain by late Pleistocene fluvial terrace deposits. Zaca Ridge, the high peak on the skyline at left edge of photo, is underlain by folded Miocene Monterey Formation. Photograph taken by Donald S. Sweetkind, U.S. Geological Survey, September 2010. Geologic and Geophysical Maps of the Santa Maria and Part of the Point Conception 30’×60’ Quadrangles, California By Donald S. Sweetkind, Victoria E. Langenheim, Kristin McDougall-Reid, Christopher C. Sorlien, Shiera C. Demas, Marilyn E. Tennyson, and Samuel Y. Johnson Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3472 Supersedes USGS Open-File Reports 95–25 and 92–189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2021 Supersedes USGS Open-File Reports 95–25 and 92–189 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov/. -

Basques in the Americas from 1492 To1892: a Chronology

Basques in the Americas From 1492 to1892: A Chronology “Spanish Conquistador” by Frederic Remington Stephen T. Bass Most Recent Addendum: May 2010 FOREWORD The Basques have been a successful minority for centuries, keeping their unique culture, physiology and language alive and distinct longer than any other Western European population. In addition, outside of the Basque homeland, their efforts in the development of the New World were instrumental in helping make the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America what they are today. Most history books, however, have generally referred to these early Basque adventurers either as Spanish or French. Rarely was the term “Basque” used to identify these pioneers. Recently, interested scholars have been much more definitive in their descriptions of the origins of these Argonauts. They have identified Basque fishermen, sailors, explorers, soldiers of fortune, settlers, clergymen, frontiersmen and politicians who were involved in the discovery and development of the Americas from before Columbus’ first voyage through colonization and beyond. This also includes generations of men and women of Basque descent born in these new lands. As examples, we now know that the first map to ever show the Americas was drawn by a Basque and that the first Thanksgiving meal shared in what was to become the United States was actually done so by Basques 25 years before the Pilgrims. We also now recognize that many familiar cities and features in the New World were named by early Basques. These facts and others are shared on the following pages in a chronological review of some, but by no means all, of the involvement and accomplishments of Basques in the exploration, development and settlement of the Americas.