Ungarn-Jahrbuch 1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

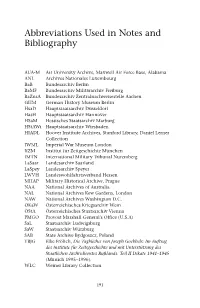

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Ons Stad Nr 71

EDITORIAL Damals ie werden immer weniger, die Manner und Frauen, die Luxemburg und der Zweite Weltkrieg - das ist inzwischen sich noch ganz genau erinnern können an jene Zeit Geschichte. vor nunmehr über 60 Jahren, als die Souveränität unseres Die großartige Ausstellung "...et wor alles net esou kleinen Staates an einem Frühlingstag innerhalb von einfach" im Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, wenigen Stunden brutal vergewaltigt wurde, als die dank des großen Publikumserfolges - weit über deut-schePanzer die Schlagbäume der Grenzübergänge wie 22.000 Besucher wurden gezählt - bis zum 24. Streichhölzer umknickten und Luxemburg von den Nazis November 2002 verlängert wurde, hat jedoch eindrucks- "heim ins Reich" geholt werden sollte. voll bewiesen, dass auch heute noch bei breiten Die, die sich noch daran erinnern, als ob es gestern Bevölkerungsschichten ein starkes Interesse an diesem gewesen wäre, sie träumen immer noch von braunen Thema besteht. Uniformen, von Zügen, die sie in die Lager oder an die Die vorliegende Ons Stad-Nummer versucht, dieser verhasste Front brachten, wo sie auf der falschen Seite Tatsache Rechnung zu tragen. kämpfen mussten. Und wer offenen Auges durch die Stadt geht - das zeigt Sie erinnern sich an Umsiedlung und Angst, an Bomben u.a. der reich illustrierte Beitrag von Andre Hohengarten und Terror, an Standgerichte, an die Villa Pauly, an (S. 5-11), der findet sie auch heute noch überall, die deut-scheStraßennamen, an das Winterhilfswerk, an den Spuren und Zeugnisse aus einem düsteren Kapitel der Reichsarbeitsdienst, an die Gedelit und an den Gelben europäischen Geschichte. Stern, den die Juden an der Brust tragen mussten, ehe sie deportiert und vergast wurden. -

In Love with Life

IN LOVE WITH LIFE Edmond Israel IN LOVE WITH LIFE AN AMERICAN DREAM OF A LUXEMBOURGER Interviewed by Raymond Flammant Pampered child Refugee Factory worker International banker ——————— New Thinking SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2006 IN LOVE WITH LIFE An American Dream of a Luxembourger by Edmond Israel ISBN 1-888112-13-1 Copyright 2006 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825-1000. This book is based on La vie, passionnément Entretiens avec Raymond Flammant French edition published in 2004 by Editions Saint Paul, Luxembourg I dedicate these pages to all those who brought light and warmth to my life. I thank my dear wife Renée for her counsel and advice. I express my particular appreciation to Raymond Flammant, who asked me the right questions. Thanks also to my assistant, Suzanne Cholewka Pinai, for her efficient help. Contents Foreword by Anthony J. Cernera ix Preface xiii Part One / DANCING ON A VOLCANO 1. Pampered Child 3 The Roaring Twenties in Europe 3 Cocooning in the family fold 8 School and self-education 14 The first signs of a devastating blaze 23 The dilemma: die or die in trickles? 27 The “Arlon” plan 30 Part Two / SURVIVING, LIVING, CONSTRUCTING 2. Refugee 35 The rescue operation “Arlon” 35 Erring on the roads of France 38 Montpellier or “The symphony in black” 40 Marseille: a Scottish shower and men with a big heart 43 The unknown heroes of Gibraltar 48 From Casablanca to the shores of liberty 49 viii / CONTENTS 3. -

Zweete Weltkrich

D'Occupatioun Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich 75 Joer Liberatioun Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich 75 Joer Liberatioun 75 Joer Fräiheet! 75 Joer Fridden! 5 Lëtzebuerg am Zweete Weltkrich. 75 Joer Liberatioun 7 D'Occupatioun 10 36 Conception et coordination générale Den Naziregime Dr. Nadine Geisler, Jean Reitz Textes Dr. Nadine Geisler, Jean Reitz D'Liberatioun 92 Corrections Dr. Sabine Dorscheid, Emmanuelle Ravets Réalisation graphique, cartes 122 cropmark D'Ardennenoffensiv Photo couverture Photothèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Tony Krier, 1944 0013 20 Lëtzebuerg ass fräi 142 Photos rabats ANLux, DH-IIGM-141 Photothèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Tony Krier, 1944 0007 25 Remerciements 188 Impression printsolutions Tirage 800 exemplaires ISBN 978-99959-0-512-5 Editeur Administration communale de Pétange Droits d’auteur Malgré les efforts de l’éditeur, certains auteurs et ayants droits n’ont pas pu être identifiés ou retrouvés. Nous prions les auteurs que nous aurons omis de mentionner, ou leurs ayants droit, de bien vouloir nous en excuser, et les invitons à nous contacter. Administration communale de Pétange Place John F. Kennedy L-4760 Pétange page 3 75 Joer Fräiheet! 75 Joer Fridden! Ufanks September huet d’Gemeng Péiteng de 75. Anniversaire vun der Befreiung gefeiert. Eng Woch laang gouf besonnesch un deen Dag erënnert, wou d’amerikanesch Zaldoten vun Athus hir an eist Land gefuer koumen. Et kéint ee soen, et wier e Gebuertsdag gewiescht, well no véier laange Joren ënner der Schreckensherrschaft vun engem Nazi-Regime muss et de Bierger ewéi en neit Liewe virkomm sinn. Firwat eng national Ausstellung zu Péiteng? Jo, et gi Muséeën a Gedenkplazen am Land, déi un de Krich erënneren. -

The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933- 1945

THE FUNCTION OF SELECTION IN NAZI POLICY TOWARDS UNIVERSITY STUDENTS 1933- 1945 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial hlfillment of the requirernents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History York University North York, Ontario December 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogaphic Services se~cesbibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your tlk Votre refénmce Our fi& Notre refdrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or elecîronic formats. la forme de microfiche/tilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Towards a New Genus of Students: The Function of Selection in Nazi Policy Towards University Students 1933-1945 by Béla Bodo a dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of York University in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF YORK UNlVERSlrY to lend or seIl copies of this dissertation, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this dissertation and to lend or sel1 copies of the film. -

Ettelbrück 1940-45 Sankt Anna Und Der Krieg

Ettelbrück 1940-45 Sankt Anna und der Krieg Inhalt Vorwort 1. Der Bericht 2. Das Pensionat 3. Der Kriegsverlauf 4. Sankt Anna im Krieg Vorwort Als Mitglied des Netzwerks der UNESCO-Schulen war es für die Privatschule Sainte-Anne selbstverständlich an dem Projekt „Rucksakbibliothéik“ teilzunehmen. Gilt es als Bildungsanstalt zwar vor allem die Jugendlichen auf eine sich immer schneller verändernde ZukunK vorzubereiten, so darf der Blick in die Ver- gangenheit jedoch nicht zu kurz kommen. Seit Jahren bemühen wir uns, unsere Schülerinnen projektorienOert an der Aufar- beitung der Vergangenheit teilnehmen zu lassen und ihnen so die Geschichte greiParer und verständlicher werden zu lassen. Die Teilnahme an Gedenkzeremonien, die jährlichen Studien- reisen, die Zeitzeugenbesuche sowie die SensibilisierungsakOo- nen an den Gedenktagen sind fest im Schulgeschehen verankert. Dieses E-Book über die Geschichte des Pensionats im 2. Weltkrieg verbindet viele Anliegen, die unserer Schulgemein- schaK wichOg sind. Erstens ist es schülerorienOert, denn gemein- sam wurde am Text gefeilt und geforscht, um ein Produkt zu er- stellen, das für heuOge Jugendliche gut verständlich ist. Gle- ichzeiOg stellt es eine Auseinandersetzung mit den neuen Medi- en dar. Das Digitalisieren, Verarbeiten und Gestalten des Buches wurde miVels neuer Medien, die immer mehr zu den Kernkom- petenzen des Alltags gehören, ausgeführt. Und schließlich wer- den durch dieses Buch die Werte unserer SchulgemeinschaK bestäOgt. Der Zusammenhalt und der respektvolle Umgang in unserer Schule basiert auf einer langen TradiOon und werden auch in ZukunK hochgehalten. Allen Schülerinnen und Lehrer/innen, die am Projekt beteiligt waren, gilt mein aufrichOger Dank. Nun aber wird es Zeit in die bewegte Vergangenheit unserer SchulgemeinschaK einzu- tauchen. -

Cinema and the Swastika

Cinema and the Swastika October-2010 MAC/CIN Page-i 9780230_238572_01_prexxiv Also by Roel Vande Winkel NAZI NEWSREEL PROPAGANDA IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR Also by David Welch NAZI PROPAGANDA: The Powers and the Limitations PROPAGANDA AND THE GERMAN CINEMA 1933–45 THE THIRD REICH: Politics and Propaganda HITLER: Profile of a Dictator October-2010 MAC/CIN Page-ii 9780230_238572_01_prexxiv Cinema and the Swastika The International Expansion of Third Reich Cinema Edited by Roel Vande Winkel and David Welch October-2010 MAC/CIN Page-iii 9780230_238572_01_prexxiv © Editorial matter, selection, introduction and chapter 1 © Roel Vande Winkel and David Welch, 2007, 2011 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2007, 2011 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in hardback 2007 and this paperback edition 2011 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

La « Question Juive » Au Luxembourg (1933-1941) L'etat Luxembourgeois

VINCENT ARTUSO LA « QUESTION JUIVE » AU LUXEMBOURG (1933-1941) L’E TAT LUXEMBOURGEOIS FACE AUX PERSECUTIONS ANTISEMITES NAZIES Rapport final Validé par le Comité scientifique présidé par Michel Pauly et constitué des membres suivants : Manuel Dillmann Paul Dostert Benoît Majerus Michel Margue Marc Schoentgen Corinne Schroeder Denis Scuto Remis au Premier ministre le 9 février 2015 VINCENT ARTUSO LA « QUESTION JUIVE » AU LUXEMBOURG (1933-1941) L’E TAT LUXEMBOURGEOIS FACE AUX PERSECUTIONS ANTISEMITES NAZIES Rapport final REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à remercier en tout premier lieu Serge Hoffmann dont l’initiative citoyenne finit par convaincre l’ensemble des forces politiques du pays et sans lequel ce rapport n’aurait pas vu le jour. Je remercie également, pour leurs conseils avisés, les membres du comité scientifique : son président, Michel Pauly, Manuel Dillmann, Paul Dostert, Benoît Majerus, Michel Margue, Marc Schoentgen, Corinne Schroeder et Denis Scuto. Quatre chercheurs n’ont pas hésité à me communiquer le fruit de leur travail, alors que celui-ci n’avait pas encore été publié : Georges Buchler, Didier Boden, Thierry Grosbois et Cédric Faltz. Leur confiance a grandi ce rapport, je leur en suis particulièrement reconnaissant. Je remercie aussi le président du Consistoire israélite de Luxembourg, Claude Marx, pour sa disponibilité et son souci de préserver les archives de la communauté juive ainsi que Jane Blumenstein pour son très chaleureux accueil à la congrégation Ramat Orah, au mois d’octobre 2014. J’adresse enfin mes remerciements au personnel des Archives nationales du Luxembourg, de la Bibliothèque nationale de Luxembourg, de l’ITS à Bad Arolsen et du YIVO Institute for Jewish Research ainsi que du Joint, à New York. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 3. Records of the National Socialist German Labor Party The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1958 This finding aid, prepared under the direction of the Committee for the Study of War Documents of the American Historical Association, has been reproduced by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this list has been deposited in the National Archives by the American Historical Association and may be identified as Microcopy No. T-81. It may be consulted at the National Archives, A price list appears on the last page. Those desiring to purchase microfilm should write to the Exhibits and Publications Branch, National Archives, Washington 25, D. C. AMERICAN HISTORICAL AS COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAR GUIDtb r<j G^RljiN ittiOOKDo LICROFlUJuD AT ALDXAr-jDRIA, VA. No. 3. Records of the National Socialist German Labor Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) Guide No, 3 has been brought up to date through alterations in the Roll, Provenance, and Item columns of pages 6, 8-11, 21-23, and 43-44 > affecting Rolls 10, 13-15, 19-20, 57,;R57B, 58, 60, 86, R87, and 88 of Microcopy No. T-81, respectively. All changes have the effect of making additional folders avail- able. The price list at the end of the guide has been adjusted accordingly, January 1963 THE AMERICAN JII3TORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMFITTEE FOR TEE STUDY OF WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAIIDRIA, VA. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis Zum Geleit 9 Vorwort 11 Die Geschichte Luxemburgs während des 2. Weltkrieges Kurze Übersicht 13 Vorschlag für einen alternativen Stadtrundgang 29 1 Erstes öffentliches Auftreten des Gauleiters - Erste Proteste 31 2 „Gedelit" 33 3 Befreiung der Hauptstadt 35 4 Schloßschenke - Kameradschaftsheim 37 5 Propagandaamt 39 6 Beschlagnahme von Radioapparaten 41 7 Dresdner Bank 43 8 Großherzogin Charlotte 45 9 Julius SCHMIEDECK im Exil 49 10 Abteilung II - Schulwesen 51 11 Wunderwaffe V3 - „Trösterin der Betrübten der Umsiedlung" .... 53 12 Luftschutzkaserne 57 13 Landesbibliothek 59 14 Deutscher Oberbürgermeister-„Unio'n" 61 15 Treffpunkt der Kollaborateure 63 16 „Boulevard Franklin Delano ROOSEVELT" .... 65 17 „Gelle Fra" 67 18 Adolf-Brücke 69 19 Zerstörung der Synagoge 71 20 Gestapochef Fritz HARTMANN - „Casino de Luxembourg" 73 21 Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrerkorps (NSKK) . 75 22 Nationalsozialistische Sturmabteilung (SA) 77 23 „Spengelskrich" 79 24 „Hinzerter Kräiz" 81 http://d-nb.info/1043519270 25 Deutsches Lazarett 83 26 Litfaßsäule 85 27 Freiheitsstein 87 28 Rüstungskommando 89 29 „Villa Pauly" 91 30 Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) 95 31 Deutsche Eisenbahnverwaltung - Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF) - „Eagle Tac" ... 97 32 Odyssee des luxemburgischen Goldes 101 33 „Adolf-Hitler-Straße" - Großkundgebungen 103 34 Deutsche Umsiedlungs-Treuhandgesellschaft (DUT) . 105 35 Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle (VOMI) - Deutscher Rechtswahrerbund in Luxemburg (DRB) 107 36 „Rue de la Greve" 109 37 „Place des Martyrs" 113 38 „Rue du Plebiscite" 115 39 Verwaltungssitz des Gauleiters Gustav SIMON - ARBED 117 40 Stillhaltekommissar 121 41 Moselland-Verlag 123 42 Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) 125 43 SS-Standartenführer Walter SCHELLENBERG . 127 44 Abteilung IV der Zivilverwaltung 129 45 Kriminalpolizei - Befehlsstelle des Luftschutzes . 131 46 Deutsche Emigranten-Amerikanische Offiziermesse . -

Der Erstinstanzliche Prozessalltag in Der Zeit Von 1938 Bis 1950 22

Der erstinstanzliche Prozessalltag an Untergerichten im Dritten Reich und in der Nachkriegszeit ist bisher nur Gegenstand weniger Untersuchungen. Kerstin Strohmaier lenkt den Fokus mittels der Auswertung eines im Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen verwahr- ten Bestands der R-Akten auf den Prozessalltag an dem im Zentrum Oberschwabens gelegenen Landgericht Ravensburg anhand des Zerrüttungstatbestandes des § 55 Ehegesetz 1938 bzw. § 48 Ehegesetz 1946. Der Einfluss der nationalsozialistischen Ideologie auf die Rechtsprechung des Landgerichts Ravensburg wird eben- Kerstin Strohmaier so ausgeleuchtet wie die Verhältnisse nach Kriegsende und Der erstinstanzliche Prozessalltag die Frage nach der Entnazifizierung nationalsozialistischen Rechts. in der Zeit von 1938 bis 1950 Eine Betrachtung des Aktenbestandes zum Zerrüttungs- tatbestand im Zeitraum von 1938 bis 1950 ermöglicht anhand der Ehescheidungsakten zugleich eine vergleichende Betrachtung der Recht- des Landgerichts Ravensburg zu sprechung und des Prozessalltags während der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus und in den Nachkriegsjahren. § 55 EheG 1938 und § 48 EheG 1946 Dabei werden auch die an den untersuchten Scheidungs- verfahren beteiligten Ehegatten und deren persönliche und wirtschaftliche Verhältnisse berücksichtigt. Zugleich gibt die Autorin einen Überblick über die an die- sen Verfahren mitwirkenden Juristen. Der Schwerpunkt liegt auf der politischen Haltung dieser Richter und Rechtsanwälte, dem Einfluss dieser Haltung auf das berufliche Fortkommen und die Argumentation in den Scheidungsverfahren sowie auf dem Entnazifizierungsverfahren und den dort gefunde- nen Ergebnissen. Kerstin Strohmaier: Der erstinstanzliche Prozessaltag in der Zeit von 1938 bis 1950 Der erstinstanzliche Prozessaltag Strohmaier: Kerstin ISBN 978-3-96374-036-7 ISBN: 978-3-96374-036-7 9 783963 740367 Rechtskultur Wissenschaft Rechtskultur Wissenschaft 9 783963 740367 22 Rechtskultur Wissenschaft Der erstinstanzliche Prozessalltag an Untergerichten im Dritten Reich und in der Nachkriegszeit ist bisher nur Gegenstand weniger Untersuchungen.