Los-Diablos-Del-Ritmo.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discos Fuentes

082 Por Chucky García www.shock.com.co EL SELLO MÁS LONGEVO DE COLOMBIA ceLEBRA SIN BAUTIZADOS ACHAQUES Y EN EL PUNTO DE MAYOR INFLUENCIA EN LAS AGUAS FUENTES DE SU CATÁLOGO. DAMAS Y CABALLEROS: CON USTEDES, LA QUINTAESENCIA DE LO BAILABLE. ECHANDO PASO TOY SELECtaH SIMÓN MEJÍA, DE BOMBA ESTÉREO LOS 75 AÑOS DE DISCOS FUENTES (MOnteRREY) Hace unos años quería hacer un documental sobre Joe “Siendo de Monterrey y siendo un amante de la cumbia, Arroyo, y andaba buscando sus discos, pero los de vinilo. es imposible no tener por lo menos diez placas de Fuentes: Buscando en Bazurto me encontré con algunas joyas tengo de Andrés Landero, Afrosound, Lisandro Mesa y Fruko del Joe en su época con Fruko y Sus Tesos, donde salían y Sus Tesos, y varios álbumes de Los Corraleros de Majagual. en las portadas con ropa entre hippie y evangélica. Cuenta la leyenda urbana que ‘la Colombia’ (la música Detallando los discos vi ese logo inconfundible de Discos de Colombia) llegó al barrio por allá por los 60, cuando Fuentes en cada vinilo, e investigando descubrí que PÓLVORA Y BIKINIS unos jornaleros mexicanos en Texas invitaron a un amigo además eran los responsables de generar una industria colombiano a pasar las navidades. El parcero llegó con alrededor de la música tropical en Colombia y de Vol. 01 Era tal la cantidad de éxitos puras joyitas de Discos Fuentes". expandir la cumbia por Latinoamérica”. que publicaba la empresa de www.myspace.com/toyselectahdj www.myspace.com/bombaestereo don Antonio Fuentes, que en 1961 sus hijos tuvieron la idea de crear un álbum en el que JUAN DIEGO BORda, PERNETT se presentaran al público los PALENKE SOULTRIbe (BARRANQUILLA/CALI) mayores éxitos de su fábrica. -

2018 158 Aliados Y Medios Edición Circulart 2018 Diseño Y Diagramación Maria Del Rosario Vallejo Gómez

CONTENIDO 6 Presentación 14 Circulart Conecta 17 Invitados Eventos Teóricos 41 Sesiones de Pitch 49 Artistas Showcases / Seleccionados por convocatoria 71 Artistas Showcases / Presentados por aliados 87 Artistas Showcases / Invitados especiales 95 Profesionales Rueda de Negocios 123 Agencias de Management y/o Sellos discográficos 135 Directorio de Artistas Rueda de Negocios 145 Feria 153 Equipo Circulart 2018 158 Aliados y medios Edición Circulart 2018 Diseño y Diagramación Maria del Rosario Vallejo Gómez. DV Humberto Jurado Grisales. DV Fotografías Invitados Circulart 2018 CIRCULART es un modelo de cultura empresarial para las artes desarrollado por REDLAT COLOMBIA PRESENTACIÓN Circulart, para esta novena versión, tiene presente la nueva realidad en la que la cultura y las artes se presentan como un nuevo ámbito para la incorporación de valor a muy diversas actividades sociales y económicas. Desde esta óptica, en asocio con la Alcaldía de Medellín y Comfama, hemos asumido una perspectiva de impacto regional y local, que se suma a la plataforma latinoamericana que mantendremos con el alto nivel que ha sido su signo, y afrontaremos un trabajo continuo a lo largo del año ligado al emprendimiento y a la innovación en la industria musical. La innovación en nuestro caso constituye un fuerte vínculo que potencia la libre circulación de ideas creativas con las realidades prácticas de la vida económica. Se trata de un ámbito que requiere habilidad y competencia para avanzar en la mejora de las modalidades de actuación. Y es que uno de los principales valores agregados, tanto de productos como de bienes y servicios, proviene hoy en día en gran medida de la aplicación del conocimiento y la creatividad, de la relación con el ámbito de la investigación tecnológica, del diseño, la comunicación, la gestión y la vida cultural en las ciudades, potenciando así el rol de la música en una plataforma de emprendimiento. -

Narrativas Cantadas De La Salsa De Los Años 70 – 80 En Colombia Una Mirada Decolonial a Las Identidades

NARRATIVAS CANTADAS DE LA SALSA DE LOS AÑOS 70 – 80 EN COLOMBIA UNA MIRADA DECOLONIAL A LAS IDENTIDADES. Lic. HECTOR F. PULIDO G. Cód.: 2010287572 Director FRANCISCO PEREA MOSQUERA Magister en Educación MAESTRÍA EN EDUCACIÓN BOGOTÁ. D.C. 2014 2 NARRATIVAS CANTADAS DE LA SALSA DE LOS AÑOS 70 – 80 EN COLOMBIA UNA MIRADA DECOLONIAL A LAS IDENTIDADES. HÉCTOR FREDY PULIDO GALINDO Tesis de grado para optar al título de: Magíster en Educación Director SPI: Magister en Educación FRANCISCO PEREA MOSQUERA MAESTRÍA EN EDUCACIÓN ÉNFASIS DE EDUCACIÓN COMUNITARIA, INTERCULTURALIDAD Y AMBIENTE Grupo de Investigación: Etnicidad, Colonialidad e Interculturalidad BOGOTÁ. D.C. 2014 3 NOTA DE ACEPTACIÓN ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Firma del presidente del jurado ________________________ Firma de jurado 1 ___________________________ Firma de jurado 2 _______________________________ Bogotá, Noviembre de 2014 4 RESUMEN ANALÍTICO EN EDUCACIÓN – RAE 1. Información General Tipo de documento Tesis de Grado Acceso al documento Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Biblioteca Central NARRATIVAS CANTADAS DE LA SALSA DE LOS AÑOS 70 – 80 EN COLOMBIA. UNA MIRADA Título del documento DECOLONIAL A LAS IDENTIDADES. Autor(es) HECTOR FREDY PULIDO GALINDO Director FRANCISCO PEREA MOSQUERA Publicación Bogotá, Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, 2014, 115 págs. Unidad Patrocinante UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA NACIONAL Narrativas -

Download File

Reinterpreting the Global, Rearticulating the Local: Nueva Música Colombiana, Networks, Circulation, and Affect Simón Calle Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Simón Calle All rights reserved ABSTRACT Reinterpreting the Global, Rearticulating the Local: Nueva Música Colombiana, Networks, Circulation, and Affect Simón Calle This dissertation analyses identity formation through music among contemporary Colombian musicians. The work focuses on the emergence of musical fusions in Bogotá, which participant musicians and Colombian media have called “nueva música Colombiana” (new Colombian music). The term describes the work of bands that assimilate and transform North-American music genres such as jazz, rock, and hip-hop, and blend them with music historically associated with Afro-Colombian communities such as cumbia and currulao, to produce several popular and experimental musical styles. In the last decade, these new fusions have begun circulating outside Bogotá, becoming the distinctive sound of young Colombia domestically and internationally. The dissertation focuses on questions of musical circulation, affect, and taste as a means for articulating difference, working on the self, and generating attachments others and therefore social bonds and communities This dissertation considers musical fusion from an ontological perspective influenced by actor-network, non-representational, and assemblage theory. Such theories consider a fluid social world, which emerges from the web of associations between heterogeneous human and material entities. The dissertation traces the actions, interactions, and mediations between places, people, institutions, and recordings that enable the emergence of new Colombian music. In considering those associations, it places close attention to the affective relationships between people and music. -

La Cumbia Por: Mario Godoy Aguirre

La Cumbia Por: Mario Godoy Aguirre Origen, generalidades. La cumbia originaria del valle del río Magdalena (Colombia), es un crisol de ritmos afro caribeños y melodías hispano americanas, adaptadas a las diferentes idiosincrasias culturales de los países que la han adoptado. La cumbia, ha impactado con fuerza y se interpreta y baila, desde México (Cumbia sonidera, norteña, grupera, callera, del sureste, etc.), hasta la Patagonia. En Argentina ahora está vigente la “Cumbia Villera” y la “cumbia digital”. Se habla de la cumbia: panameña, salvadoreña, mexicana (sonidera), peruana (amazónica, sanjuanera), ecuatoriana, andina, chicha, etc. La cumbia, es un género que gusta mucho a la mayoría de ecuatorianos y Latinoamericanos. La cumbia es la “lingua franca” o lengua vehicular de Latinoamérica, es el género musical del entendimiento común, es un “elemento vertebrador de la identidad latinoamericana en Latinoamérica y la diáspora… Funcionando como un punto de referencia social dentro de estos países así como en el actual fenómeno migratorio que ha esparcido ciudadanos latinoamericanos por todo el planeta”,1 repitiendo la tesis de J. Attali, citado por Rubén López Cano: “la música va por delante de la sociedad. Nuestro futuro va a sonar a cumbia por activa o por pasiva. Por aceptación o por rechazo, por hibridación o por autoafirmación”2. Especialmente entre los mestizos citadinos, desde finales de los años cincuenta del siglo XX, la cumbia, y otros géneros “populares” de la música colombiana se han bailado en el Ecuador con gran aceptación. Discos Fuentes3 incluyó en su catálogo y circuito comercial, a las cumbias de la costa Atlántica de Colombia. -

Evolución Del Diseño Visual a Través Del Análisis Gráfico De Carátulas

Evolución del diseño visual a través del análisis gráfico de carátulas musicales del género Rap Juan Pablo Roa Cuervo Juan Sebastián Rico Cárdenas Christian Julián Molano Moreno Luis David Buitrago Pérez Proyecto de trabajo de grado presentado como requisito para optar al título de: Diseño Visual. Diseñador Visual Fundación Universitaria Compensar Comunicación Diseño Visual Bogotá, Colombia 2020 Evolución del diseño visual a través del análisis gráfico de carátulas musicales del género Rap Juan Pablo Roa Cuervo Juan Sebastián Rico Cárdenas Christian Julián Molano Moreno Luis David Buitrago Pérez Proyecto de trabajo de grado presentado como requisito para optar al título de: Diseño Visual. Diseñador Visual Tutor (a): MFA Sergio Andrés Nieto Línea de Investigación: Diseño, Medios y Mercadeo Fundación Universitaria Compensar Comunicación Diseño Visual Bogotá, Colombia 2020 Agradecimientos Agradecemos de antemano y de toda sinceridad al profesor Sergio Andrés Nieto por haber confiado en nosotros por animarnos a emprender la elaboración de esta tesis, por su colaboración y orientación sobre todas las dudas surgidas durante el desarrollo de este documento, ya que, con sus valiosos conocimientos y disponibilidad de tiempo, permitieron ejecutar lo que aquí está escrito. Declaración Los autores certifican que el presente trabajo es de su autoría, para su elaboración se han respetado las normas de citación tipo APA, de fuentes textuales y de parafraseo de la misma forma que las citas de citas y se declara que ninguna copia textual supera las 400 palabras. Por tanto, no se ha incurrido en ninguna forma de plagio, ni por similitud ni por identidad. Los autores son responsables del contenido y de los juicios y opiniones emitidas. -

Lo Quiere El Negro?: Racialized Representations of Women in La Sonora Dinamita’S Cumbias

UCLA Thinking Gender Papers Title ¿Ay mama, que será lo quiere el negro?: Racialized Representations of Women in La Sonora Dinamita’s Cumbias Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2jc955k7 Author Jiménez, Gabriela Publication Date 2010-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 ¿Ay mama, que será lo quiere el negro?: Racialized Representations of Women in La Sonora Dinamita’s Cumbias Gabriela Jiménez Race is a complex social component in Colombia and across much of the Americas (Wade 1993, 3). Although scholars have written of Latin American exceptionalism — arguing that racial democracy, compared to racist ideology in the United States, prevailed in Latin America (Sawyer 2006, 21) — the beginnings of contemporary racial dynamics cemented a much more complicated social trajectory; Francesca Miller captures these moments symbolically: “The imagery of the ‘conquest of the Americas’ is overwhelmingly sexual: the white Spanish male, in armor, on horseback, shooting firearms in the ‘virgin territory.’ The visible woman in these accounts is the Indian woman, beautiful, dark, supine, the fruit of the new Eden. The literal and metaphoric imagery is of rape” (1991, 23). To this description of forced miscegenation add centuries of involuntary and voluntary flows of people. Miller’s quote also accounts for the importance of gender and sexuality. Placed in opposition to the aggressive armed white man is the passive indigenous female who embodies sin. Racialization was, and continues to be, gendered and sexualized. Consequently, an examination of racially-gendered codes is of relevance — where race, gender and sexuality are loaded terms best understood currently as social constructs with vast sociological effects. -

Universidad Distrital Francisco José De Caldas

UNIVERSIDAD DISTRITAL FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE CALDAS FACULTAD DE ARTES ASAB PROYECTO CURRICULAR DE ARTES MUSICALES DIGITALIZACIÓN, CATALOGACION Y PESQUISA INVESTIGATIVA SOBRE LAS AGRUPACIONES PERTENECIENTES AL SONIDO PAISA ORIGINADO EN MEDELLIN EN LOS AÑOS SESENTA JULIÁN ANDRÉS VARGAS RODRÍGUEZ CÓDIGO: 20161098035 ÉNFASIS INTÉRPRETE: TROMBÓN TUTORA: GLORIA MILLÁN GRAJALES MODALIDAD: INVESTIGACIÓN-INNOVACIÓN BOGOTÁ 2020 RESUMEN El Trabajo de Grado Digitalización, Catalogación y Pesquisa Investigativa Sobre las Agrupaciones Pertenecientes al Sonido Paisa Originado en Medellín en los Años Sesenta, aporta la digitalización y catalogación de 346 archivos sonoros relacionados con las agrupaciones Los Teen Agers, Los Hispanos, Los Graduados, Los Golden Boys, El Conjunto Miramar, Los Black Stars, Los Falcons, entre otros, los cuales pertenecen al Fondo de Documentos Sonoros Antonio Cuéllar del Centro de Documentación de las Artes (CDA) de la Facultad de Artes ASAB que pertenece a la Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Siguiendo las directrices de la IASA para la digitalización y catalogación de archivos sonoros, se entregan como resultados archivos en formato .WAV, con fines de conservación y en MP3 con el fin de facilitar su difusión, generados a partir de soportes analógicos de 45, 78 y 33 revoluciones por minuto (RPM). A su vez, el proceso de catalogación busca complementar la base de datos SIRES del CDA, en donde reposan los datos del Fondo de Documentos Sonoros Antonio Cuéllar. Adicionalmente se realizó una pesquisa investigativa que permite conocer el origen y la trayectoria de las agrupaciones del Sonido Paisa, hasta que llegaron a consolidarse en la escena musical del país. Palabras clave: Digitalización, Catalogación, Pesquisa Investigativa, Discografía, Sonido Paisa. -

Recorded at Discos Fuentes, Medellín, Colombia

1 hese days, when being wary of technology makes you look as though you are slightly stuck in the past, music producers Mario Galeano (Frente Cumbiero, Colombia) Tand William Holland (Quantic, UK), decided to return to old techniques in search of the spirit, texture and sound of a time when music perhaps sounded better. With full conviction, these two producers, who are like graduates in a school of researchers who look for what lies hidden in the grooves of old vinyl LPs, give us Ondatrópica, a master-class of craftsmanship shaped into sound. As a music lover and member of Colombian Public Radio, I consider myself privileged to have witnessed the intense and joyous recording sessions of Ondatrópica in the Discos Fuentes studios during January 2012. Few things in life are as priceless as seeing with your own eyes—and hearing with your own ears—Pedro ‘Ramayá’ Beltran conjuring up modernity in a rap; colourful Michi Sarmiento behind his sax and singing like he did back in the sixties with the Combo Bravo; Markitos Micolta serenading us on why he wants to live to be a hundred years old; or accordionist Aníbal ‘Sensación’ Velásquez paying the respect he deserves to the great Andrés Landero. And there was nothing more satisfying than to see everyone show how our musical heritage is a vehicle for a cross-over of generations, sound traditions, and infl uences. I know that listeners worldwide will gladly embrace this piece of Colombia materialized on an LP, and also this timeless gathering of our nation’s musical talent: Guepajé! Jaime Andrés Monsalve Musical Director, Radio Nacional de Colombia 2 3 AN INTRODUCTION BY WILL HOLLAND & MARIO GALEANO: fter several years of working in and around Colombian tropical music, we were given the opportunity to create a large-scale project involving an iconic selection of Colombian musicians in a classic and mythical studio Asetting, using completely analogue recording equipment and benefi ting from an inter-generational meeting between the new and the old guard. -

La Industria Musical En Medellín 1940-1960: Cambio Cultural, Circulación De Repertorios Y Experiencias De Escucha

LA INDUSTRIA MUSICAL EN MEDELLÍN 1940-1960: CAMBIO CULTURAL, CIRCULACIÓN DE REPERTORIOS Y EXPERIENCIAS DE ESCUCHA Juan David Arias Calle Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Medellín Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Económicas Departamento de Historia Medellín, Colombia 2011 1 LA INDUSTRIA MUSICAL EN MEDELLÍN 1940-1960: CAMBIO CULTURAL, CIRCULACIÓN DE REPERTORIOS Y EXPERIENCIAS DE ESCUCHA Juan David Arias Calle Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar el título de Magister en Historia Director: Doctor Jorge William Montoya Santamaría Línea de investigación en Historia Social y de la Cultura Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Medellín Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Económicas Departamento de Historia Medellín, Colombia 2011 2 Para Yiyi, que hace felices mis días a su lado. A mis tíos Fernando y Magally Arias 3 CRÉDITOS Esta tesis fue posible gracias al apoyo financiero que recibió de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia y de la Dirección de Investigación Sede Medellín - DIME, que a través de la Convocatoria Nacional de 2009, Modalidad 5, financió junto con esta un importante número de Tesis de la XI Cohorte de la Maestría en Historia. 4 RESUMEN Este trabajo describe los principales desarrollos de la industria musical en Medellín entre 1940 y 1960; registra las transformaciones operadas en las condiciones materiales de escucha, por la evolución técnica de los reproductores sonoros; y ofrece algunos ejemplos de los intensos y variados intercambios musicales que se presentaron en la cultura popular latinoamericana, producto del crecimiento acelerado en la producción y consumo de contenidos musicales, y que se vivieron con especial intensidad en Medellín en el período elegido. -

The Quantic Soul Orchestra Stampede Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Quantic Soul Orchestra Stampede mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul Album: Stampede Country: UK Released: 2014 Style: Future Jazz, Downtempo, Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1826 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1538 mb WMA version RAR size: 1418 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 794 Other Formats: WMA AIFF WAV DXD AC3 RA AA Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Stampede 3:09 Raw Ingredients A2 3:49 Trombone – Damian Bell Walking Through Tomorrow (Super 8 Part 3) A3 2:55 Vocals, Flute, Guitar [Lead], Written-by – John Hughes A4 South Coastin' 5:19 Something That's Real A5 4:16 Arranged By [Strings], Violin – Antonia PheulatosVocals, Written-By – Alice Russell Hold It Down B1 2:53 Vocals – Alice RussellWritten-By – D. McFarlane* B2 Assassin 4:11 Terrapin B3 3:12 Written-By – Simon Green Babarabatiri B4 2:36 Written-By – Antar Daly Take Your Time, Change Your Mind B5 6:48 Vocals, Written-By – Alice Russell Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tru Thoughts Ltd. Copyright (c) – Tru Thoughts Ltd. Credits Clavinet, Organ [Rhodes], Trumpet – Dave Woodhouse Drums – Richard Gibbs* Liner Notes [December 2002] – Robert Luis Saxophone – Lucy Holland Written-By, Arranged By, Producer, Guitar, Bass, Percussion – Will Holland Notes Ltd Repress on 180g vinyl + download card Drums recorded in various bedrooms with the help of Richard Magraa. All tracks recorded in the West Midlands and Brighton, UK. © & ℗ Tru Thoughts Ltd. 2003 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 050491 005911 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category -

Programmerve2009.Pdf

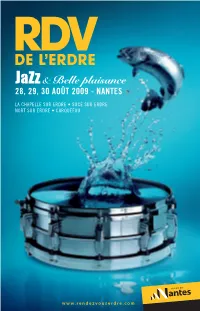

Programmation musicale des Rendez-vous de l’Erdre JAZZ 1 www.rendezvouserdre.com Programmation musicale des Rendez-vous de l’Erdre JAZZ 3 omme chaque année, en ce bout d’été, le cœur de Nantes va battre sur les bords de l’Erdre. La rivière a rendez-vous avec le jazz et avec le Cpatrimoine maritime et fluvial pour faire partager à plus de 150 000 spectateurs de chaleureux moments de convivialité. Les Rendez-vous de Le festival Les Rendez-vous de l’Erdre l’Erdre, reconnus aujourd’hui comme l’un des festivals de jazz les plus créatifs est membre de l’AFIJMA (Association des et les plus étonnants de l’Hexagone, sont un moment privilégié qui nous Festivals Innovants en Jazz et Musiques ouvre de nouveaux horizons artistiques et culturels. En ces jours de rentrée, Actuelles). cette grande fête populaire du jazz et cet exceptionnel rassemblement Créée en 1993, l’Afijma regroupe de bateaux à vapeur sont une nouvelle invitation à redécouvrir cet aujourd’hui 30 festivals de jazz contemporain et de musiques improvisées environnement rare et préservé de l’Erdre. Il offre un décor unique pour une en France. Parmi ses objectifs, l’Afijma manifestation généreuse qui accueille tous les styles du jazz pour un festival oeuvre à la valorisation du jazz français et à la ligne artistique forte, ouvert à l’émergence, à la création, à la découverte européen, et travaille au développement des artistes de la scène nantaise et régionale et aussi, évidemment, à de d’échanges internationaux dans le but de favoriser la programmation de musiciens nombreuses têtes d’affiches européennes et américaines qui font la grande étrangers en France et celle de musiciens histoire du jazz.