The Reformation in Spain in the Sixteenth Century (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

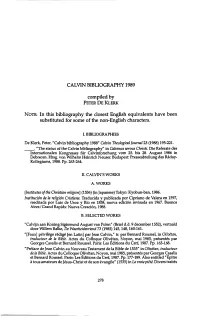

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1989 Compiled By

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1989 compiled by PETER DE KLERK NOTE: In this bibliography the closest English equivalents have been substituted for some of the non-English characters. I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1988" Calvin Theological Journal 23 (1988) 195-221. "The status of the Calvin bibliography" in Calvinus servus Christi. Die Referate des Internationalen Kongresses für Calvinforschung vom 25. bis 28. August 1986 in Debrecen. Hrsg. von Wilhelm Heinrich Neuser. Budapest: Presseabteilung des Ráday- Kollegiums, 1988. Pp. 263-264. II. CALVIN'S WORKS Α. WORKS [Institutes of the Christian religion] (1536) (in Japanese) Tokyo: Kyobun-ban, 1986. Institución de la religión Cristiana. Traducida y publicada por Cipriano de Valera en 1597, reeditada por Luis de Usoz y Río en 1858, nueva edición revisada en 1967. Buenos Aires/Grand Rapids: Nueva Creación, 1988. B. SELECTED WORKS "Calvijn aan Koning Sigismund August van Polen" (Brief d.d. 9 december 1552), vertaald door Willem Balke, De Waarheidsvriend 73 (1985) 145,148,160-161. "[Faux] privilège rédigé [en Latin] par Jean Calvin," tr. par Bernard Roussel, in Olivétan, traducteur de la Bible. Actes du Colloque Olivétan, Noyon, mai 1985, présentés par Georges Casalis et Bernard Roussel. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987. Pp. 163-168. "Préface de Jean Calvin au Nouveau Testament de la Bible de 1535" in Olivétan, traducteur de la Bible. Actes du Colloque Olivétan, Noyon, mai 1985, présentés par Georges Casalis et Bernard Roussel. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987. Pp. 177-189. Also entitled "Épître à tous amateurs de Jésus-Christ et de son évangile" (1535) in ha vraie piété. -

Cipriano De Valera

id3200531 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Cipriano de Valera Nacido en Valera la Vieja (Herróbriga), entonces perteneciente al Reino de Sevilla, en 1531 o 1532, y fallecido después de 1602 al parecer en Londres. Sobre todo, es conocido como el revisor y editor de la primera traducción castellana de la Biblia desde los originales. Fue condiscípulo de Arias Montano, mientras estudiaba en Sevilla. Al terminar seis años de estudios de Filosofía, y con el grado de Bachiller, ingresó en el Monasterio Jerónimo de San Isidoro del campo, próximo a Sevilla, desde el que huyó, con otros, en 1557, a Ginebra para librarse del Tribunal de la Inquisición, que llegó a quemarlo en efigie ("por luterano") en 1562 y le colocó en el "Índice de Libros Prohibidos", como autor de primera clase. De Ginebra pasó a Londres, al subir al trono Isabel I, y allí residió el resto de sus días, menos el tiempo que le llevó en Amsterdam la impresión de la segunda edición, notablemente revisada por él, de la traducción castellana de la Biblia, que había publicado su compatriota y compañero de monasterio Casiodoro de Reina, en Basilea (1569). En Inglaterra fundó una familia, enseñó en las universidades de Cambridge y Oxford y publicó varios libros. De sus obras originales, la primera que vió la luz fue Dos Tratados. El primero el del Papa y su de autoridad, colegido de su vida y doctrina, y de lo que los doctores y concilios antiguos y la misma Sagrada Escritura enseñan. -

Casiodoro De Reina

Ensayo candidato (nivel-C) Año académico de 2007-08 Primer semestre Casiodoro de Reina La historia y la vida de un heterodoxo español Director: Juan Wilhelmi Alumno: Björn Reisnert Institución: Språk- och litteraturcentrum, Lunds Universitet 1 Índice Introducción 3 La Inquisición española 7 La España de Casiodoro de Reina 9 San Isidoro del Campo 14 Casiodoro de Reina 17 La publicación de la Biblia 26 Después de la publicación 31 Conclusión 36 Bibliografía 37 2 Casiodoro de Reina La historia y la vida de un heterodoxo español Introducción …Cassiodoro de Reyna movido de un pio zelo [benigna pasión] de adelantar la gloria de Dios, y de hazer un señalado servicio à su nacion enviendo se en tierra de libertad para hablar y tratar de las cosas de Dios, començò a darle à la traslacion de la Biblia. La qual traduxo; y assi año de 1569, imprimiò dos mil exemplares: Los quales por la misericordia de Dios se han repartido por muchas regiones. De tal manera q hoy casi no se hallan exemplares, si alguno los quiere comprar. (Cipriano de Valera, año de 1602) Este breve fragmento de texto lo encontré por casualidad, mientras, en la Biblioteca Nacional de España, estaba ojeando la “Exhortación al lector” de una Biblia castellana: LA BIBLIA. Que es, LOS SACROS LIBROS DEL VIEIO Y NVEVO TESTAMENTO de Cipriano de Valera, impresa en Ámsterdam en la casa de Lorenço Iacobi el año 1602. El fragmento, el que más tarde comentaré más en detalle, fue escrito por el fraile sevillano Cipriano de Valera en dicho año. Sin embargo, C. -

Participants in the Sufferings of Christ (1 Pet 4:13): 16Th-Century Spanish Protestant Ecclesiology

Participants in the Sufferings of Christ (1 Pet 4:13): 16th-Century Spanish Protestant Ecclesiology by Steven Richard Griffin A Thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec © Steven Richard Griffin, January 2011 CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………. iv RÉSUMÉ………………………………………………………………………. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………. vi LIST OF ACRONYMS………………………………………………………… vii INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter ONE: CONSTANTINO PONCE DE LA FUENTE (1502 – 1559) AND THE ORIGINS OF SPANISH PROTESTANTISM IN SEVILLE ……………………………………………………. 22 Erasmian Foundation…………………………………………….. 26 Valdés‘ Doctrine of Word and Spirit…………………………..... 32 Constantino Ponce de la Fuente and Reform in Seville…………. 39 Constantino Ponce de la Fuente as a Reformed Catholic………... 45 TWO: SPANISH PROTESTANT SOTERIOLOGY: ‗PARTICIPANTS IN THE SUFFERINGS OF CHRIST‘ …….... 64 The Person and Work of Christ………………………………….. 75 ii Participation in Christ……………………………………………. 80 THREE: THE MARKS AND AUTHORITY OF GOD‘S ‗LITTLE FLOCK‘……………………………………………..… 98 Church as Catholic ‗Little Flock‘………………………………... 99 Scripture and Tradition(s)……………………………………….. 109 The Marks of the True Church…………………………………... 123 FOUR: CEREMONIES ‗OUTSIDE THE CAMP‘……………………..... 136 Corro: Lively Images of Divine Mercy………………………….. 138 Reina: External Instruments of Justification……………………... 154 The Sacrament of the Word……………………………………… 171 FIVE: ‗BEARING THE DISGRACE -

The Doctrine of Prevenient Grace in the Theology of Jacobus Arminius

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2017 The Doctrine of Prevenient Grace in the Theology of Jacobus Arminius Abner F. Hernandez Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hernandez, Abner F., "The Doctrine of Prevenient Grace in the Theology of Jacobus Arminius" (2017). Dissertations. 1670. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1670 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT THE DOCTRINE OF PREVENIENT GRACE IN THE THEOLOGY OF JACOBUS ARMINIUS by Abner F. Hernandez Fernandez Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE DOCTRINE OF PREVENIENT GRACE IN THE THEOLOGY OF JACOBUS ARMINIUS Name of researcher: Abner F. Hernandez Fernandez Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: April 2017 Topic This dissertation addresses the problem of the lack of agreement among interpreters of Arminius concerning the nature, sources, development, and roles of prevenient grace in Arminius’s soteriology. Purpose The dissertation aims to investigate, analyze, and define the probable sources, nature, development, and role of the concept of prevenient or “preceding” grace in the theology of Jacobus Arminius (1559–1609). Sources The dissertation relies on Arminius’s own writings, mainly the standard London Edition, translated by James Nichols and Williams Nichols. -

Biblismo, Lengua Vernácula Y Traducción En Casiodoro De Reina Y Cipriano De Valera

ISSN: 1579-9794 Biblismo, lengua vernácula y traducción en Casiodoro de Reina y Cipriano de Valera (Casiodoro de Reina and Cipriano de Valera’s biblicism, vernacular language and translation) JUAN LUIS MONREAL PÉREZ [email protected] Universidad de Murcia Fecha de recepción: 26 de septiembre de 2014 Fecha de aceptación: 1 de noviembre de 2014 Resumen: El examen de la contribución de Casiodoro de Reina y Cipriano de Valera a la lengua vulgar hay que hacerlo en el contexto de tres corrientes culturales que agitan el periodo renacentista europeo y que encuentran, igualmente, su expresión en la España de aquel tiempo: Erasmismo, Reformismo y Biblismo. Por otra parte, el uso de la lengua vernácula en ambos necesita ser visto desde una perspectiva histórico- lingüista amplia, que permita ver tanto la influencia que éstos recibieron de la tradición anterior, a través de las traducciones de la Biblia al castellano, como el uso que éstos hicieron de la lengua castellana. Sus aportaciones a la lengua española se han hecho a través de las dos traslaciones de la Biblia que llevaron a cabo, y que fueron realizadas con las ideas y los criterios que expusieron en sus correspondientes introducciones al texto que denominaron Amonestación y Exhortación. Palabras clave: Erasmismo, Reformismo, Biblismo, Lengua Vernácula, Traslación. Abstract: Examination of the contribution of Casiodoro de Reina and Cipriano de Valera to the vernacular language must be made in the context of three cultural currents that shook the European Renaissance period and found equal expression in the Spain of that time: Erasmianism, Reformism and Biblicism. Moreover, the use of the vernacular language by these two authors needs to be viewed from a broad historical-linguist perspective which allows one to view both the influence they received from the previous tradition, through translations of the Bible into Spanish, as well as the use they made of the Spanish language. -

Anti-Spanish Sentiment in English Literary and Political Writing 1553

Anti-Spanish sentiment in English literary and political writing 1553-1603 Mark G Sanchez Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The University of Leeds The School of English June, 2004 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my PhD research supervisor, Dr. Michael G. Brennan,for his unstinting supportand scholarlyguidance from 2000 to 2004. I would also like to thank the Schoolof English, and in particular ProfessorDavid Fairer, for having offered me the chanceto study at Leedsduring the last eight years. Finally, I would like to expressmy thanks to Dr. Bernard Linares, the Gibraltarian Minister for Education and Training, and to the librarians and staff of the Brotherton University Library, Leeds. 11 Abstract This thesis examines anti-Spanish sentiment within Marian and Elizabethan literary and political writing. Although its primary aim is to reinvigorate the reader's perceptions about a topic that has traditionally been subject to considerable scholarly neglect, four `core' objectives can still be identified (a) to demonstrate how `anti-Spanishness' began as a deliberate, highly systematic attempt to tackle a number of unresolved issues within the minds -

Antonio Del Corro

BIBLIOTHECA WIFFENIANA. BIBLIOTHECA WIFFENIANA. SPANISH REFORMERS OF TWO CENTURIES FROM 1520. THEIR LIVES AND WRITINGS, ACCORDING TO THE LATE BENJAMIN B. WIFPEN'S PLAN AND WITH THE USE OF HIS MATERIALS DESCRIBED BY EDWAED BOEHMER. THIRD "VOLUME. STRASSBURG. KARL J. TRUBNER. 1904 Printed in FrancUe's OrpVianlioiiso, Halle o/S, DEDICATED TO FREDERIK SEEBOHM AND JOHANNES MERCK. Wahrend im Riesengetriebe des britischen Reiches in Ansehn als Bankhalter Du wirkst, sinnest Du hoheres Gut. Glaubensgenosse der Seelen, die schlicht sich Freunde benennen, hast Du bedachtig erforscht, trefflich. uns Allen erzahlt wie mit den weisen Gefahrten getreulich Erasmus in Oxford gegen scholastischen Brauch biblisehe Lehre gepflegt. Du, der Hapag Mitleiter, die jetzo der grosseste Reader, tauchst in des Weltschrifttums heiter erfrischendes Bad. LiebevoU suchst Du die Biicher der edlen hispanischen Geister, die des befangeneu Volks herrschender Glaube verfehmt, imd so reihst Du die Perlen in wiirdiger schmuckerer Fassung, Freude dem prtifenden Blick, Zeugen von heiligem Eat. Euch auch fesselte Beide das Werk, das der sorgliche Samraler, ledig des Eisengeschafts, eisernes Fleisses geplant; Ihr unternahmt was bereit nunmehr fiir den Leser hie vorliegt, reichlich ist's Euer, wohlan: nehmt es von dankender Hand. INDEX. Antonio del Corro P. 1 Cipriano de Valera „ 147 Pedro Gal6s „ 175 Melchior Roman „ 185 ANTONIO DEL CORRO. Biblioth. "Wiffen. III. The monks of the order of S. Hieronymus in San Isidro of Seville were induced by one of their number to open their hearts to purer religion, and the evangelical books which came from Geneva and Germany brought about a wonderful reform in the monastery. Worship of saints, fasting, horal prayers, masses for the dead, and other Roman practices were abolished; only the celebration of the daily mass was not discontinued, as this could not be done without drawing all eyes to the things going on at San Isidro. -

Spanish Protest.Ant Refugees in Engl.And. by Dr

264 SPANISH PROTESTANT REFUGEES IN ENGLAND SPANISH PROTEST.ANT REFUGEES IN ENGL.AND. BY DR. LIESELOTTE LINNHOFF, Author of Spanische Protestanten und England. N the 'forties and 'fifties of the sixteenth century, the Protestant I doctrine was received with great rejoicing in Spain, the two towns of Valladolid and Seville, where a great number of the noble and more refined section of the population formed the first Protestant congregations on Spanish soil, taking the lead. Also the greater part of the monasteries and nunneries in the neighbourhood of these two centres of Protestantism had been imbued with the new doctrine. Of the greatest significance were the events in the Hieronymite convent of San Isidro de! Campo, in the vicinity of Seville. Many of the monks had been converted, due chiefly to the influence of important Sevillian Protestants as Dr. Egidio, Dr. Constantino, Garci-Arias-commonly called "el Maestro Blanco" -and to the devoted study of evangelical books imported from Geneva and Germany. Within a few years, considerable reforms were introduced into monastic life: the fixed hours for prayer were now spent reading and interpreting the Bible; prayers for the dead were omitted ; papal indulgences and pardons were entirely abolished ; the concentration on the Holy Scriptures superseded the obligation of novices to submit to strict monastic rules. Only the monastic garb and the external ceremony of the Mass were retained as a precaution. A few monks, however, found it difficult to reconcile with their conscience the keeping to external rules for reasons of fear only. Therefore in 1557 twelve monks left the monastery to enjoy peace of mind and religious freedom in Protestant countries. -

July 2009 We Celebrate the Polemics Aside, So Far As Is Possible, by Five Hundredth Anniversary of the Birth Relying Heavily on Calvin ’S Own Words, of John Calvin

Trinitarian Bible Society Founded in 1831 for the circulation of Protestant or uncorrupted versions of the Word of God Officers of the Society General Committee: General Secretary: Mr. D. P. Rowland The Rev. M. H. Watts , Chairman Assistant General Secretary: The Rev. B. G. Felce, M.A. , Vice-Chairman Mr. D. Larlham The Rev. G. Hamstra, B.A., M.Div., Vice-President Editorial Manager: Mr. D. Oldham, Vice-President Mr. G. W. Anderson Mr. C. A. Wood, Vice-President Office Manager: Pastor R. A. Clarke, B.Sc., F.C.A., Treasurer Mr. J. M. Wilson Mr. G. Bidston Warehouse Manager: Mr. I. A. Docksey Mr. G. R. Burrows, M.A. Mr. G. D. Buss, B.Ed. Quarterly Record The Rev. R. G. Ferguson, B.A. Production Team Pastor M. J. Harley General Secretary: D. P. Rowland Mr. A. K. Jones Assistant General Secretary: D. Larlham Production Editor: The Rev. E. T. Kirkland, B.A., Dipl.Th. Dr. D. E. Anderson The Rev. J. MacLeod, M.A. Assistants to the Editor: C. P. Hallihan, D. R. Field, K. J. Pulman The Rev. D. Silversides Graphic Designer: P. Hughes The Rev. J. P. Thackway Circulation: J. M. Wilson © Trinitarian Bible Society 2009 All rights reserved. The Trinitarian Bible Society permits Issue Number: 588 reprinting of articles found in our printed and online Quarterly Record provided that prior permission is July to September 2009 obtained and proper acknowledgement is made. Contents Annual General Meeting 2 From the Desk of the General Secretary 3 The Treasury 10 The Resurrection and the Life 11 Open Doors in South America 13 Calvin at Five Hundred 26 The Word of God Among All Nations 44 Trinitarian Bible Society will be held, God willing at 11.00am on Saturday, 26 th September 2009 at the Metropolitan Tabernacle, Elephant and Castle, London, SE1 The Rev. -

The Protestant Reformation: Returning to the Word of God

The /,1"91+1 "#,/*1&,+Returning to the Word of God C. P. HALLIHAN The Prote§tant "#,/*ation Returning to the Word of God C. P. Hallihan Trinitarian Bible Society London, England The Protestant Reformation: Returning to the Word of God Product Code: A128 ISBN 978 1 86228 066 3 ©2017 Trinitarian Bible Society William Tyndale House, 29 Deer Park Road London SW19 3NN, England Registered Charity Number: 233082 (England) SC038379 (Scotland) Copyright is held by the Incorporated Trinitarian Bible Society Trust on behalf of the Trinitarian Bible Society. Contents: . A Prologue 2 . Before 1517 4 . The Renaissance 11 . Erasmus 15 . Up to and after 1517 20 . Luther’s Translation of the Bible 24 . Geneva: John Calvin 1509–1564 31 . Europe: Other Reformation-era Bibles 37 . London-Oxford-Cambridge: The English Reformation 42 . Bibles and Reformation in the British Isles 48 . Trento (Trent): The Counter Reformation 52 . Appendices 55 v The Prote§tant "#,/*1&,+ Returning to the Word of God C. P. Hallihan he Reformation of the sixteenth century is, next to the introduction of Christianity, the greatest event in history. It marks the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern times. Starting from religion, it gave, directly or indirectly, a mighty impulse to every forward movement, and made Protestantism the chief propelling force in the history of modern civilisation.1 Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church The issues of the Reformation are set out in the unique illustration Effigies praecipuorum illustrium atque praestantium aliquot theologorum by the engraver Hans Schwyzer about 1650. Dominating the table in the centre we have the light of the Gospel. -

Spanish-Bible-Reina-Valera-Historic

Historical facts about the Spanish translation of the Holy Bible (Reina Valera 1909) Copyright www.crystal-bible.com Origin of the “Bible Spanish translation from Reina Valera ”: The Reina-Valera, published in 1569 and nicknamed the Bible of the Bear, was the first complete edition of the Bible in the Spanish language . Casiodoro de Reina (1520-1594), a former Roman Catholic monk and an Independent Evangelical, published his translation of the Bible in 1569. For the Old Testament, This translation was based on the Hebrew Masoretic Text (Bomberg's Edition, 1525), Jewish translation called the Ladino Ferrara Bible (printed 1553) and the Greek Textus Receptus (Stephanus' Edition, 1550). Also, Reina was aided by Vetus Latina for the Old Testament and the Latin Edition of Santes Pagnini throughout. The Old Testament was aided by translations of Francisco de Enzinas and Juan Pérez de Pineda as well. Casiodoro de Reina had a few problems. It omitted the words "by faith" in Romans 3:28, omitted all of Hebrews 12:29 ("For our God is a consuming fire") and included the Apocrypha. [The Apocrypha remained in the Reina-Valera until the "Santa Biblia" edition in 1862.] One of his friends was Cipriano de Valera (1531-1602+), another former monk. In 1596 Valera published a revised translation of the New Testament, and in 1602 he finished the complete Bible in Spanish, following the Textus Receptus more than Reina had. The New Testament probably derives from the Textus Receptus of Erasmus with comparisons to the Vetus Latina and Syriac manuscripts. It is possible that Reina also used the New Testament versions that had been translated first by Francisco de Enzinas (printed in Antwerp 1543) and by Juan Pérez de Pineda (published in Geneva 1556, followed by the Psalms 1562).