The Protestant Reformation: Returning to the Word of God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Biblioteca Nacional De Colombia Procesos

BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA PROCESOS TÉCNICOS REPORTE DE REGISTROS DEL FONDO DANILO CRUZ VÉLEZ Total registros en la Base de Datos de la Biblioteca Nacional: 3.556 ISBN: 958-18-0127-8 (Obra Completa) ISBN: 958-18-0137-5 Autor personal: Zalamea Borda, Eduardo, 1907-1963 Título: 4 años a bordo de mí mismo / Eduardo Zalamea Borda Pie de imprenta: Colombia : Imprenta Nacional, 1996 Descripcion física: 313 p. ; 21 cm A 110863 F. DANILO 2505 Título: 9 Asedios a García Márquez / Benedetti ... [et.al.] Pie de imprenta: Santiago de Chile : Editorial Universitaria, ©1969 Descripcion física: 181 p. ; 19 cm F. DANILO 2610 Autor personal: Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616 Título: 20 sonetos / de William Shakespeare Pie de imprenta: Bogotá : Arte Dos Gráficos, 1996 Descripcion física: 53 p. ; 24 cm F. DANILO 405 Título: 70 años de narrativa argentina, 1900-1970 / [prólogo, selección y notas de Roberto Yahni] Pie de imprenta: Madrid : Alianza Editorial, 1970 Descripcion física: 212 p. ; 19 cm F. DANILO 1403 N 68144 PN 31087 ISBN: 3-445-01948-7 Título: 90 Jahre philosophische Nietzsche-Rezeption / Alfredo Guzzoni (Hrsg.) Pie de imprenta: Königstein : Verlag Anton Hain Meisenheim Gmbh, c1979 Descripcion física: x, 189 p. ; 22 cm F. DANILO 3742 1 Autor personal: Heidegger, Martín, 1889-1976 Título: 700 Jahre Stadt Messkirch : Festansprachen zum 700-jährigen Messkircher stadtjubiläum 22. bis 30 / Martin Heidegger, Bernhard Welte, Altgraf Salm Pie de imprenta: München : [s n.], [1961?] Descripcion física: 36 p. ; fot. ; 21 cm F. DANILO 2318 Autor personal: Russell, Bertrand, 1872-1970 Título: El A.B.C. de la relatividad / Russell Bertrand Pie de imprenta: Buenos Aires : Ediciones Imán, 1943 Descripcion física: 194 p. -

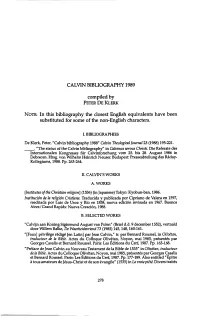

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1989 Compiled By

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1989 compiled by PETER DE KLERK NOTE: In this bibliography the closest English equivalents have been substituted for some of the non-English characters. I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1988" Calvin Theological Journal 23 (1988) 195-221. "The status of the Calvin bibliography" in Calvinus servus Christi. Die Referate des Internationalen Kongresses für Calvinforschung vom 25. bis 28. August 1986 in Debrecen. Hrsg. von Wilhelm Heinrich Neuser. Budapest: Presseabteilung des Ráday- Kollegiums, 1988. Pp. 263-264. II. CALVIN'S WORKS Α. WORKS [Institutes of the Christian religion] (1536) (in Japanese) Tokyo: Kyobun-ban, 1986. Institución de la religión Cristiana. Traducida y publicada por Cipriano de Valera en 1597, reeditada por Luis de Usoz y Río en 1858, nueva edición revisada en 1967. Buenos Aires/Grand Rapids: Nueva Creación, 1988. B. SELECTED WORKS "Calvijn aan Koning Sigismund August van Polen" (Brief d.d. 9 december 1552), vertaald door Willem Balke, De Waarheidsvriend 73 (1985) 145,148,160-161. "[Faux] privilège rédigé [en Latin] par Jean Calvin," tr. par Bernard Roussel, in Olivétan, traducteur de la Bible. Actes du Colloque Olivétan, Noyon, mai 1985, présentés par Georges Casalis et Bernard Roussel. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987. Pp. 163-168. "Préface de Jean Calvin au Nouveau Testament de la Bible de 1535" in Olivétan, traducteur de la Bible. Actes du Colloque Olivétan, Noyon, mai 1985, présentés par Georges Casalis et Bernard Roussel. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1987. Pp. 177-189. Also entitled "Épître à tous amateurs de Jésus-Christ et de son évangile" (1535) in ha vraie piété. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Calvin, the Church, and Displaced Persons

TTJ 13.2 (2010): 137-151 ISSN 1598-7140 Calvin, the Church, and Displaced Persons Elsie Ann McKee Princeton Theological Seminary, USA The name John Calvin is so closely associated with the Swiss city, Geneva, and its international connections that it is often forgotten that he was, in fact, a resident alien in a small political entity without pre- tentions to university culture, precariously balanced between hungry larger states. Calvin came from France, an exile for his faith. He had not intended to settle in Geneva but was compelled by the conviction that God and the church were calling him through the mouth of William Farel. Geneva itself did not much want Calvin, this foreigner whom they accepted, exiled, and called back because they decided they needed him, this foreigner with whom they struggled as both pastor and city learned to live together for the sake of the faith they shared. Calvin had only to speak and it was obvious to any Genevan citizen that he was not one of them. Furthermore, he attracted ever increasing numbers of other religious refugees from his native France and also sig- nificant numbers of exiles speaking Italian, English, and Spanish. The composition of their city was changing and their traditions were chal- lenged. Calvin for his part tried to minister as faithfully as possible in Geneva – faithfulness including kinds of Christian formation (education and discipline) which Genevans did not necessarily appreciate – but his eyes and heart were always at least partly focused on France and the scattered worshiping congregations there and in exile. -

Scenario Book 1

Here I Stand SCENARIO BOOK 1 SCENARIO BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S ABOUT THIS BOOK ......................................................... 2 Controlling 2 Powers ........................................................... 6 GETTING STARTED ......................................................... 2 Domination Victory ............................................................. 6 SCENARIOS ....................................................................... 2 PLAY-BY-EMAIL TIPS ...................................................... 6 Setup Guidelines .................................................................. 2 Interruptions to Play ............................................................ 6 1517 Scenario ...................................................................... 3 Response Card Play ............................................................. 7 1532 Scenario ...................................................................... 4 DESIGNER’S NOTES ........................................................ 7 Tournament Scenario ........................................................... 5 EXTENDED EXAMPLE OF PLAY................................... 8 SETTING YOUR OWN TIME LIMIT ............................... 6 THE GAME AS HISTORY................................................. 11 GAMES WITH 3 TO 5 PLAYERS ..................................... 6 CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMATION ...................... 15 Configurations ..................................................................... 6 EVENTS OF THE REFORMATION -

Opening God's Word to the World

AMERICAN BIBLE SOCIETY | 2013 ANNUAL REPORT STEWARDSHIP God’S WORD GOES FORTH p.11 HEALING TRAUMA’S WOUNDS p.16 THE CHURCh’S ONE FOUNDATION p.22 OPENING GOd’s WORD TO THE WORLD A New Chapter in God’s Story CONTENTS Dear Friends, Now it is our turn. As I reflect on the past year at American Bible Society, I am Nearly, 2,000 years later, we are charged with continuing this 4 PROVIDE consistently reminded of one thing: the urgency of the task before important work of opening hands, hearts and minds to God’s God’s Word for Millions Still Waiting us. Millions of people are waiting to hear God speak to them Word. I couldn’t be more excited to undertake this endeavor with through his Word. It is our responsibility—together with you, our our new president, Roy Peterson, and his wife, Rita. 6 Extending Worldwide Reach partners—to be faithful to this call to open hands, hearts and Roy brings a wealth of experience and a passionate heart for 11 God’s Word Goes Forth minds to the Bible’s message of salvation. Bible ministry from his years as president and CEO of The Seed This task reminds me of a story near the end of the Gospel Company since 2003 and Wycliffe USA from 1997-2003. He of Luke. Jesus has returned to be with his disciples after the has served on the front lines of Bible translation in Ecuador and resurrection. While he is eating fish and talking with his disciples, Guatemala with Wycliffe’s partner he “opened their minds to understand the Scriptures.” Luke 24.45 organization SIL. -

Andrés Laguna: Translation and the Early Modern Idea of Europe1

ANDRÉS LAGUNA: TRANSLATION AND THE EARLY MODERN IDEA OF EUROPE1 JOSÉ MARÍA PÉREZ FERNÁNDEZ ENGLISH DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF GRANADA I In 1539 a Spanish visitor witnessed a cockfight in London. He was surprised at the enthusiastic response of the spectators—even more so when among the audience of what he described as a childish and vile form of entertainment there were some very distinguished gentlemen. One of them, a man of raro ingenio (rare wit) in the description of the Spaniard, must have been piqued by the explicit distaste of a stranger and came forward in defence of the show. In addition to the pastime it provided, he claimed, the disinterested courage displayed by these creatures in a mortal engagement could not fail to inspire any captain, or prince, to fight with at least equal valour for their offspring, their religion, or the honour and well-being of their homeland. The visitor was immediately persuaded by the lively eloquence of the Englishman: “Las quales razones tan viuas, adornadas de palabras muy elegantes, luego me conuencieron”. The Spaniard in question was the Hellenist and physician Andrés Laguna, and the story appears embedded in one of the commentaries to his Spanish translation of the Dioscorides. His English interlocutor was “Thomas Huuyat, hombre de raro ingenio, el qual hauia sido Embaxador ciertos años en la corte de la Cesarea”, i.e. the diplomat and poet Sir Thomas Wyatt.2 Laguna had already given an account of the public spectacles he witnessed in England a few years before: in a commentary to the entry on Liberalitas to his 1543 translation of the pseudo- Aristotelian De virtutibus (Cologne, 1543, p. -

Manichaean Exonyms and Autonyms (Including Augustine's Writings)

Page 1 of 7 Original Research Manichaean exonyms and autonyms (including Augustine’s writings) Author: Did the Western Manichaeans call themselves ‘Manichaean’ and ‘Christian’? A survey of Nils A. Pedersen1,2 the evidence, primarily Latin and Coptic, seems to show that the noun and adjective uses of ‘Manichaean’ were very rarely used and only in communication with non-Manichaeans. The Affiliations: 1Department of Culture and use of ‘Christian’ is central in the Latin texts, which, however, is not written for internal use, Society, Aarhus University, but with a view to outsiders. The Coptic texts, on the other hand, are written for an internal Denmark audience; the word ‘Christian’ is only found twice and in fragmentary contexts, but it is suggested that some texts advocate a Christian self-understanding (Mani’s Epistles, the Psalm- 2Research Fellow, Department of Church Book) whilst others (the Kephalaia) are striving to establish an independent identity. Hence, the History and Polity, University Christian self-understanding may reflect both the earliest Manichaeism and its later Western of Pretoria, South Africa form whilst the attempt to be independent may be a secondary development. Note: Contribution to ‘Augustine and Manichaean Introduction Christianity’, the First South African Symposium Augustine starts his work On Heresies from the years 428–429 with these words: on Augustine of Hippo, I write something on heresies that is worth reading for those who desire to avoid teachings which are University of Pretoria, contrary to the Christian faith and which, nonetheless, deceive others, because they bear the Christian name.1 24−26 April 2012. Dr Nils Pedersen is participating as So basically heresies are teachings that contain an anti-Christian faith, even though they still research fellow of Prof. -

Robert M. Andrews the CREATION of a PROTESTANT LITURGY

COMPASS THE CREATION OF A PROTESTANT LITURGY The development of the Eucharistic rites of the First and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI ROBERT M. ANDREWS VER THE YEARS some Anglicans Anglicanism. Representing a study of have expressed problems with the Archbishop Thomas Cranmer's (1489-1556) Oassertion that individuals who were liturgical revisions: the Eucharistic Rites of committed to the main tenets of classical 1549 and 1552 (as contained within the First Protestant theology founded and shaped the and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI), this early development of Anglican theology.1 In essay shows that classical Protestant beliefs 1852, for example, the Anglo-Catholic were influential in shaping the English luminary, John Mason Neale (1818-1866), Reformation and the beginnings of Anglican could declare with confidence that 'the Church theology. of England never was, is not now, and I trust Of course, Anglicanism changed and in God never will be, Protestant'.2 Similarly, developed immensely during the centuries in 1923 Kenneth D. Mackenzie could, in his following its sixteenth-century origins, and 1923 manual of Anglo-Catholic thought, The it is problematic to characterize it as anything Way of the Church, write that '[t]he all- other than theologically pluralistic;7 nonethe- important point which distinguishes the Ref- less, as a theological tradition its genesis lies ormation in this country from that adopted in in a fundamentally Protestant milieu—a sharp other lands was that in England a serious at- reaction against the world of late medieval tempt was made to purge Catholicism English Catholic piety and belief that it without destroying it'.3 emerged from. -

Cipriano De Valera

id3200531 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Cipriano de Valera Nacido en Valera la Vieja (Herróbriga), entonces perteneciente al Reino de Sevilla, en 1531 o 1532, y fallecido después de 1602 al parecer en Londres. Sobre todo, es conocido como el revisor y editor de la primera traducción castellana de la Biblia desde los originales. Fue condiscípulo de Arias Montano, mientras estudiaba en Sevilla. Al terminar seis años de estudios de Filosofía, y con el grado de Bachiller, ingresó en el Monasterio Jerónimo de San Isidoro del campo, próximo a Sevilla, desde el que huyó, con otros, en 1557, a Ginebra para librarse del Tribunal de la Inquisición, que llegó a quemarlo en efigie ("por luterano") en 1562 y le colocó en el "Índice de Libros Prohibidos", como autor de primera clase. De Ginebra pasó a Londres, al subir al trono Isabel I, y allí residió el resto de sus días, menos el tiempo que le llevó en Amsterdam la impresión de la segunda edición, notablemente revisada por él, de la traducción castellana de la Biblia, que había publicado su compatriota y compañero de monasterio Casiodoro de Reina, en Basilea (1569). En Inglaterra fundó una familia, enseñó en las universidades de Cambridge y Oxford y publicó varios libros. De sus obras originales, la primera que vió la luz fue Dos Tratados. El primero el del Papa y su de autoridad, colegido de su vida y doctrina, y de lo que los doctores y concilios antiguos y la misma Sagrada Escritura enseñan. -

Donald Macleod God Or God?: Arianism, Ancient and Modern

Donald Macleod God or god?: Arianism, Ancient and Modern Ancient heresies have a habit of recurring in the Christian church. Although this article deals with eighteenth century tendencies, it may help to alert readers to the danger of compamble phenomena in contempomry theology and their effects on the teaching of the church. Beliefin the Dei1y ofJesus Christ is well waITanted by the canonical scriptures of the Christian church. When we move, however, from exegesis and biblical theology to the realm of systematic reflection we soon find ourselves struggling. The statement ~esus Christ is God' (or 'any statement linking such a subject to such a predicate) raises enormous problems. What is the relation of Christ as God to God the Father? And what is his relation to the divine nature? These questions were raised in an acute form by the Arian controversy of the 4th century. The church gave what it hoped were definitive answers in the Nicene Creed of 325 and the Nicaeno Constantinopolitan Creed of 381, but, despite these, Arianism persisted long after the death of the heresiarch. This article looks briefly at 4th century developments, but focuses mainly on later British Arianism, particularly the views of the great Evangelical leaders, Isaac Watts and Philip Doddridge. Arius It is a commonplace that history has been unkind to heretics. In the case of such men as Praxeas and Pelagius we know virtually nothing of their teaching except what we can glean from the voluminous writings of their opponents (notably Tertullian and Augustine). Arius (probably born in Libya around 256, died 336) is in little better case.