Federalism and Low-Maintenance Constituencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Federalism on National Party Cohesion in Brazil

National Party Cohesion in Brazil 259 SCOTT W. DESPOSATO University of Arizona The Impact of Federalism on National Party Cohesion in Brazil This article explores the impact of federalism on national party cohesion. Although credited with increasing economic growth and managing conflict in countries with diverse electorates, federal forms of government have also been blamed for weak party systems because national coalitions may be divided by interstate conflicts. This latter notion has been widely asserted, but there is virtually no empirical evidence of the relationship or even an effort to isolate and identify the specific features of federal systems that might weaken parties. In this article, I build and test a model of federal effects in national legislatures. I apply my framework to Brazil, whose weak party system is attributed, in part, to that country’s federal form of government. I find that federalism does significantly reduce party cohesion and that this effect can be tied to multiple state-level interests but that state-level actors’ impact on national party cohesion is surprisingly small. Introduction Federalism is one of the most widely studied of political institutions. Scholars have shown how federalism’s effects span a wide range of economic, policy, and political dimensions (see Chandler 1987; Davoodi and Zou 1998; Dyck 1997; Manor 1998; Riker 1964; Rodden 2002; Ross 2000; Stansel 2002; Stein 1999; Stepan 1999; Suberu 2001; Weingast 1995). In economic spheres, federalism has been lauded for improving market competitiveness and increasing growth; in politics, for successfully managing diverse and divided countries. But one potential cost of federalism is that excessive political decentralization could weaken polities’ ability to forge broad coalitions to tackle national issues.1 Federalism, the argument goes, weakens national parties because subnational conflicts are common in federal systems and national politicians are tied to subnational interests. -

Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-Study*

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-study* Marta Arretche University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil The article distinguishes federal states from bicameralism and mechanisms of territorial representation in order to examine the association of each with institutional change in 32 countries by using constitutional amendments as a proxy. It reveals that bicameralism tends to be a better predictor of constitutional stability than federalism. All of the bicameral cases that are associated with high rates of constitutional amendment are also federal states, including Brazil, India, Austria, and Malaysia. In order to explore the mechanisms explaining this unexpected outcome, the article also examines the voting behavior of Brazilian senators constitutional amendments proposals (CAPs). It shows that the Brazilian Senate is a partisan Chamber. The article concludes that regional influence over institutional change can be substantially reduced, even under symmetrical bicameralism in which the Senate acts as a second veto arena, when party discipline prevails over the cohesion of regional representation. Keywords: Federalism; Bicameralism; Senate; Institutional change; Brazil. well-established proposition in the institutional literature argues that federal Astates tend to take a slow reform path. Among other typical federal institutions, the second legislative body (the Senate) common to federal systems (Lijphart 1999; Stepan * The Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado -

Types of Semi-Presidentialism and Party Competition Structures in Democracies: the Cases of Portugal and Peru Gerson Francisco J

TYPES OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIALISM AND PARTY COMPETITION STRUCTURES IN DEMOCRACIES: THE CASES OF PORTUGAL AND PERU GERSON FRANCISCO JULCARIMA ALVAREZ Licentiate in Sociology, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru), 2005. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in POLITICAL SCIENCE Department of Political Science University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Gerson F. Julcarima Alvarez, 2020 TYPES OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIALISM AND PARTY COMPETITION STRUCTURES IN DEMOCRACIES: THE CASES OF PORTUGAL AND PERU GERSON FRANCISCO JULCARIMA ALVAREZ Date of Defence: November 16, 2020 Dr. A. Siaroff Professor Ph.D. Thesis Supervisor Dr. H. Jansen Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. J. von Heyking Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Y. Belanger Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the influence that the semi-presidential form of government has on the degree of closure of party competition structures. Thus, using part of the axioms of the so-called Neo-Madisonian theory of party behavior and Mair's theoretical approach to party systems, the behavior of parties in government in Portugal (1976-2019) and Peru (1980-1991 and 2001-2019) is analyzed. The working hypotheses propose that the president-parliamentary form of government promotes a decrease in the degree of closure of party competition structures, whereas the premier- presidential form of government promotes either an increase or a decrease in the closure levels of said structures. The investigation results corroborate that apart from the system of government, the degree of closure depends on the combined effect of the following factors: whether the president's party controls Parliament, the concurrence or not of presidential and legislative elections, and whether the party competition is bipolar or multipolar. -

Sub-National Second Chambers and Regional Representation: International Experiences Submission to Kelkar Committee on Maharashtra

Sub-national Second Chambers and regional representation: International Experiences Submission to Kelkar Committee on Maharashtra By Rupak Chattopadhyay October 2011 The principle of the upper house of the legislature being a house of legislative review is well established in federal and non-federal countries like. Historically from the 17th century onwards, upper houses were constituted to represent the legislative interests of conservative and corporative elements (House of Lords in the UK or Senate in Bavaria or Bundesrat in Imperial Germany) against those of the ‘people’ as represented by elected lower houses (e.g. House of Commons). The United States became the first to use the upper house as the federating chamber for the country. This second model of bicameralism is that associated with the influential ‘federal’ example of the US Constitution, in which the second chamber was conceived as a ‘house of the states’. It has been said in this regard that federal systems of government are highly conducive to bicameralism in which a senate serves as a federal house whose members are selected to represent the states or provinces, with each constituent state provided equal representation. The Australian Senate was conceived along similar lines, with the Constitution guaranteeing each state, again regardless of its population, an equal number of senators. At present, the Australian Senate consists of 76 senators, 12 from each of the six states and two from each of the mainland territories.60 The best contemporary example of a second chamber which does, in fact, operate as an effective ‘house of the states’ is the German Bundesrat, members of which are appointed by state governments from amongst their members, with each state having between three and six representatives, depending on population. -

Establishing a Lebanese Senate: Bicameralism and the Third Republic

CDDRL Number 125 August 2012 WORKING PAPERS Establishing a Lebanese Senate: Bicameralism and the Third Republic Elias I. Muhanna Brown University Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Working Paper of the Program on Arab Reform and Democracy at CDDRL. About the Program on Arab Reform and Democracy: The Program on Arab Reform and Democracy examines the different social and political dynamics within Arab countries and the evolution of their political systems, focusing on the prospects, conditions, and possible pathways for political reform in the region. This multidisciplinary program brings together both scholars and practitioners - from the policy making, civil society, NGO (non-government organization), media, and political communities - as well as other actors of diverse backgrounds from the Arab world, to consider how democratization and more responsive and accountable governance might be achieved, as a general challenge for the region and within specific Arab countries. The program aims to be a hub for intellectual capital about issues related to good governance and political reform in the Arab world and allowing diverse opinions and voices to be heard. It benefits from the rich input of the academic community at Stanford, from faculty to researchers to graduate students, as well as its partners in the Arab world and Europe. Visit our website: arabreform.stanford.edu Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. -

Romanian Chamber of Deputies (Camera Deputaţilor)

ROMANIAN CHAMBER OF DEPUTIES (CAMERA DEPUTAŢILOR) Last updated in January 2021 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/relnatparl [email protected] Photo credits: Romanian Chamber of Deputies 1. AT A GLANCE Romania is a constitutional republic with a democratic multiparty parliamentary system. The bicameral parliament (Parlamentul României) consists of the Senate (Senat) and the Chamber of Deputies (Camera Deputaţilor). The Chamber of Deputies and the Senate are elected every four years by universal, equal, direct, secret, and freely expressed suffrage. In the 2016 legislative elections, following the amendment of electoral law in 2015, deputies and senators were elected based on a proportional electoral system, last used in the 2004 elections, and which replaced the uninominal voting system. The new electoral law provides a norm of representation of 73.000 inhabitants for deputies and 168.000 inhabitants for senators which led to a decrease in the number of MPs: from 588 to 466 parliamentary seats (312 deputies, 18 minority deputies, and 136 senators). The Romanian diaspora is represented by four deputies and two senators. 2. COMPOSITION Current situation (after the elections of 29 May 2019) Party EP affiliation % Seats Partidul Social Democrat (PSD) 28, 90 110 Social Democratic Party Partidul Naţional Liberal (PNL) National Liberal Party 25,19 93 Alianța USR-PLUS Save Romania Union (USR) and Party of Liberty, Renew Europe 15,37 55 Unity and Solidarity (PLUS) Alliance Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor (AUR) Not affiliated 9,08 33 Alliance for the Unity of Romanians Uniunea Democrată Maghiară din România (UDMR) 5,74 21 Romániai Magyar Demokrata Szövetség Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania Minoritati Naţionale Not affiliated 18 Members representing ethnic minorities Turnout: 33.30% Next legislative elections: 2024 Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments 3. -

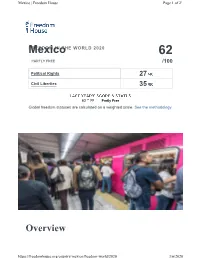

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Mexico | Freedom House Page 1 of 23 MexicoFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 62 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 27 Civil Liberties 35 63 Partly Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/mexico/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Mexico | Freedom House Page 2 of 23 Mexico has been an electoral democracy since 2000, and alternation in power between parties is routine at both the federal and state levels. However, the country suffers from severe rule of law deficits that limit full citizen enjoyment of political rights and civil liberties. Violence perpetrated by organized criminals, corruption among government officials, human rights abuses by both state and nonstate actors, and rampant impunity are among the most visible of Mexico’s many governance challenges. Key Developments in 2019 • President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who took office in 2018, maintained high approval ratings through much of the year, and his party consolidated its grasp on power in June’s gubernatorial and local elections. López Obrador’s polling position began to wane late in the year, as Mexico’s dire security situation affected voters’ views on his performance. • In March, the government created a new gendarmerie, the National Guard, which officially began operating in June after drawing from Army and Navy police forces. Rights advocates criticized the agency, warning that its creation deepened the militarization of public security. • The number of deaths attributed to organized crime remained at historic highs in 2019, though the rate of acceleration slowed. Massacres of police officers, alleged criminals, and civilians were well-publicized as the year progressed. -

The Separation of Powers in Mexico

Duquesne Law Review Volume 47 Number 4 Separation of Powers in the Article 6 Americas ... and Beyond: Symposium Issue 2009 The Separation of Powers in Mexico Jose Gamas Torruco Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jose G. Torruco, The Separation of Powers in Mexico, 47 Duq. L. Rev. 761 (2009). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol47/iss4/6 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. The Separation of Powers in Mexico Josg Gamas Torruco* I. CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS .................................. 762 II. H ISTORY ......................................................................... 765 III. PRESIDENT-PARTY SYSTEM ........................................... 770 IV. THE "TRANSITION" ........................................................ 776 V. PRESIDENT-CONGRESS .................................................. 777 A . B alances............................................................. 777 1. Intervention by the Presidentin the Legislative Process ................................ 777 2. ExtraordinaryPowers to Legislate ................................................ 778 i. Suspension of Human Rights .... 778 ii. Export and Import Tariffs ......... 778 iii. Health Emergencies ................... 778 3. Duty to Inform....................................... 779 4. FinancialActs ...................................... -

Presidential Legislative Powers

Presidential Legislative Powers International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 15 Presidential Legislative Powers International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 15 Elliot Bulmer © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2015 by International IDEA under the title Presidential Powers: Legislative Initiative and Agenda-setting International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-120-0 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ -

Italian Constitution Shall Be Entitled to the Right of Asylum Under the Conditions Established by Law

Senato della Repubblica Constitution of the Italian Republic This volume is published by the Parliamentary Information, Archives and Publications Office of the Senate Service for Official Reports and Communication Senate publications may be requested from the Senate Bookshop - by mail: via della Maddalena 27, 00186 Roma - by e-mail: [email protected] - by telephone: n. +39 06 6706 2505 - by fax: n. +39 06 6706 3398 © Senato della Repubblica CONTENTS FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES . Pag. 5 PART I – RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF CITIZENS . » 7 TITLE I – CIVIL RELATIONS . » 7 TITLE II – ETHICAL AND SOCIAL RIGHTS AND DUTIES »10 TITLE III – ECONOMIC RIGHTS AND DUTIES . » 12 TITLE IV – POLITICAL RIGHTS AND DUTIES . » 14 PART II – ORGANISATION OF REPUBLIC . » 16 TITLE I – THE PARLIAMENT . » 16 Section I – The Houses . » 16 Section II – The Legislative Process . » 19 TITLE II – THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC . » 22 TITLE III – THE GOVERNMENT . » 24 Section I – The Council of Ministers . » 24 Section II – Public Administration . » 25 Section III – Auxiliary Bodies . » 25 TITLE IV – THE JUDICAL BRANCH . » 26 Section I – The Organisation of the Judiciary . » 26 Section II – Rules on Jurisdiction . » 28 3 TITLE V – REGIONS, PROVINCES - MUNICIPALITIES . » 30 TITLE VI – CONSTITUTIONAL GUARANTEES . » 37 Section I – The Constitutional Court . » 37 Section II – Amendments to the Constitution. Constitutional Laws . » 38 TRANSITIONAL AND FINAL PROVISIONS . » 39 4 CONSTITUTION OF THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES Art. 1 Italy is a democratic Republic founded on labour. Sovereignty belongs to the people and is exercised by the people in the forms and within the limits of the Constitution. Art. 2 The Republic recognises and guarantees the inviolable rights of the person, both as an individual and in the social groups where human personality is expressed. -

The Chamber of Deputies

PARLIAMENT OF THE CZECH REPUBLIC THE CHAMBER OF DEPUTIES PARLIAMENTARY CONTROL OF THE GOVERNMENT IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC 1992, the traditional parliamentary system pre- “…the right to dissolve the Parlia- vailed. The present system represents a continua- ment and the right to express no con- tion of the model of Czechoslovak parliamentarism fi dence in the Government belong to that existed between the two World Wars, newly each other in much the same way as enriched by some elements typical particularly of a piston belongs to the cylinder of an the current French constitutional model. engine…” (Karl Loewenstein) THE SUPERVISORY POWERS THE PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEM OF THE CZECH PARLIAMENT OF GOVERNMENT Apart from its constitutional and legislative The Czech Republic belongs to the group of powers, the Czech Parliament wields a wide range countries that have a parliamentary system of gov- of supervisory powers, particularly as regards the ernment. Such a system of government has the Government. The supervisory powers of Parliament following typical characteristics: a dual executive refer to the political control or supervision exercised branch (a Head of State and a Head of Govern- by Parliament over the actions of the Government ment), the election of the President by the Parlia- and state administration. The Parliament exercises ment (in the case of republics, as opposed to con- continuous supervision of the Government and en- stitutional monarchies), the accountability of the sures that the Government respects the will and de- Government to the Parliament or to one its cham- mands of the public, as expressed by the public in bers and a personal correlation between the Go- elections to the two chambers of Parliament. -

Factsheet: Romanian Chamber of Deputies (Camera Deputaţilor)

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: Romanian Chamber of Deputies (Camera Deputaţilor) 1. At a glance Romania is a constitutional republic with a democratic multiparty parliamentary system. The bicameral parliament (Parlamentul României) consists of the Senate (Senat) and the Chamber of Deputies (Camera Deputaţilor). The Chamber of Deputies and the Senate are elected every four years by universal, equal, direct, secret, and freely expressed suffrage. In the 2016 legislative elections, following the amendment of electoral law in 2015, deputies and senators were elected based on a proportional electoral system, last used in the 2004 elections, and which replaced the uninominal voting system. The new electoral law provides a norm of representation of 73.000 inhabitants for deputies and 168.000 inhabitants for senators which led to a decrease in the number of MPs: from 588 to 466 parliamentary seats (312 deputies, 18 minority deputies, and 136 senators). The Romanian diaspora is represented by four deputies and two senators. 2. Composition Current situation (after the elections of 29 May 2019) Party EP affiliation % Seats Partidul Social Democrat (PSD) 28, 90 110 Social Democratic Party Partidul Naţional Liberal (PNL) National Liberal Party 25,19 93 Alianța USR-PLUS Save Romania Union (USR) and Party of Liberty, Renew Europe 15,37 55 Unity and Solidarity (PLUS) Alliance Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor (AUR) Not affiliated Alliance for the Unity of Romanians 9,08 33 Uniunea Democrată Maghiară din România (UDMR) 5,74 21 Romániai Magyar Demokrata Szövetség Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania Minoritati Naţionale Not affiliated 18 Members representing ethnic minorities Turnout: 33.30% Next legislative elections: 2024 3.