A Tribute to the Honourable R. Gordon Robertson, P.C., C.C., LL.D., F.R.S.C., D.C.L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Long Reach of War: Canadian Records Management and the Public Archives

The Long Reach of War: Canadian Records Management and the Public Archives by Kathryn Rose A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Kathryn Rose 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis explores why the Public Archives of Canada, which was established in 1872, did not have the full authority or capability to collect the government records of Canada until 1966. The Archives started as an institution focused on collecting historical records, and for decades was largely indifferent to protecting government records. Royal Commissions, particularly those that reported in 1914 and 1962 played a central role in identifying the problems of records management within the growing Canadian civil service. Changing notions of archival theory were also important, as was the influence of professional academics, particularly those historians mandated to write official wartime histories of various federal departments. This thesis argues that the Second World War and the Cold War finally motivated politicians and bureaucrats to address records concerns that senior government officials had first identified during the time of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Geoffrey Hayes, for his enthusiasm, honesty and dedication to this process. I am grateful for all that he has done. -

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970 by Brendan Kelly A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Brendan Kelly 2016 ii Marcel Cadieux, the Department of External Affairs, and Canadian International Relations: 1941-1970 Brendan Kelly Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Between 1941 and 1970, Marcel Cadieux (1915-1981) was one of the most important diplomats to serve in the Canadian Department of External Affairs (DEA). A lawyer by trade and Montreal working class by background, Cadieux held most of the important jobs in the department, from personnel officer to legal adviser to under-secretary. Influential as Cadieux’s career was in these years, it has never received a comprehensive treatment, despite the fact that his two most important predecessors as under-secretary, O.D. Skelton and Norman Robertson, have both been the subject of full-length studies. This omission is all the more glaring since an appraisal of Cadieux’s career from 1941 to 1970 sheds new light on the Canadian diplomatic profession, on the DEA, and on some of the defining issues in post-war Canadian international relations, particularly the Canada-Quebec-France triangle of the 1960s. A staunch federalist, Cadieux believed that French Canadians could and should find a place in Ottawa and in the wider world beyond Quebec. This thesis examines Cadieux’s career and argues that it was defined by three key themes: his anti-communism, his French-Canadian nationalism, and his belief in his work as both a diplomat and a civil servant. -

A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLIII, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2016) “A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65 Greg Donaghy1 2014-15 marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian- Hungarian diplomatic relations. On January 14, 1965, under cold blue skies and a bright sun, János Bartha, a 37-year-old expert on North Ameri- can affairs, arrived in the cozy, wood paneled offices of the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Paul Martin Sr. As deputy foreign minister Marcel Cadieux and a handful of diplomats looked on, Bartha presented his credentials as Budapest’s first full-time representative in Canada. Four months later, on May 18, Canada’s ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Mal- colm Bow, arrived in Budapest to present his credentials as Canada’s first non-resident representative to Hungary. As he alighted from his embassy car, battered and dented from an accident en route, with its fender flag already frayed, grey skies poured rain. The contrasting settings in Ottawa and Budapest are an apt meta- phor for this uneven and often distant relationship. For Hungary, Bartha’s arrival was a victory to savor, the culmination of fifteen years of diplo- matic campaigning and another step out from beneath the shadows of the postwar communist take-over and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. For Canada, the benefits were much less clear-cut. In the context of the bitter East-West Cold War confrontation, closer ties with communist Hungary demanded a steep domestic political price in exchange for a bundle of un- certain economic, consular, and political gains. -

OLIGARCHS at OTTAWA, PART II Night a Success

/ Oligarchs at Otta-wa ..: Austin F. Cross ' ' VERY year on budget night, like an to advise the minister (that's the term, E unspectacular star at the tail of but actually our man writes the stuff) on that bright comet, the Hon. Douglas the technical aspects of taxation. His Abbott, there moves into the Press Gal- is the ethical concept of taxation. Not lery ' reception rQom, among others, Ken' immediately has he to be concerned with Eaton. In title, Assistant Deputy Minister such matters as whether the Fisheries of Finance: in fact, he is the fell ow who needs the money, or Trade and Com- wrote a lot of <the budget that the Hon. merce is bungling its administration. Ra- Mr. Abbott has just so entertainingly given. ther would it be his role to assess nicely, There are other tail-stars, of course, to the what for example, would be the effect of Abbott comet. Yet paradoxically none one cent more tax on cigarettes, or the will seem duller, none will be brighter, precise incidence of sales tax. than the same Ken Eaton. For a fellow _He and Harry Perry are a very good who has just heard a lot of his own fiscal team, and when they sit down to write theory and financial policy given to the their share of the budget, you have people of Canada in particular and the a brilliant duet being played. world in general, Ken Eaton is quiet "He's without a peer in his field," said enough. an expert enthusiastically, in discussing There he sits, a man who would pass in Eaton, and this expert is one man rarely a crowd. -

Exteinsions of REMARKS FEDERAL FOOLISHNESS Rially Speaking," for His Stations

July 31, 1974 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 26187 who is deaf or deaf-blind; to the Committee to the Committee on Interior and Insular corrections in the enrollment of H.R. 69; on Ways and Means. Affa.1rs. ordered to be printed. By Mr. RONCALLO of New York: By Mr. PODELL (for htmself, Mr. By Mr. ANDERSON of California: H.R. 16193. A bill to prohibit certain con WOUT, Mr. RoSENTHAL, Mr. BIAGGI. H. Con. Res. 571. Concurrent resolution filets of interest between financial institu Mrs. CHISHOLM, Mr. CAREY of New for negotiations on the Turkish opium ban; tions and corporations regulated by certain York, Mr. MUBPBY of New York, Mr. to the Committee on Foreign Affairs. agencies of the United States; to the Com RANGEL, Mr. BADILLO, Mr. ADDABBO, ByMr.CAMP: mittee on Banking and Currency. Mr. DELANEY, Miss HOLTZ:-4AN, Mr. H. Con. Res. 572. Concurrent resolution By Mr. SHIPLEY: KocH, Ms. ABZUG, Mr. BINGHAM, and calUng for a domestic summit to develop H.R. 16194. A bill to further the purposes Mr. PEYSER) : a unified plan of action to restore stabllity of the Wilderness Act by designating cer H.R. 16202. A btll to establish tn the De and prosperity to the American economy; to tain lands for inclusion in the National partment of Housing and Urban Develop the Committee on Banking and Currency. Wilderness Preservation System, to provide ment a housing enforcement assistance pro By Mr. McCOLLISTER: for study of certain additional lands for such gram to aid cities and other municipa.l1ttes H. Con. Res. 573. -

What Has He Really Done Wrong?

The Chrétien legacy Canada was in such a state that it WHAT HAS HE REALLY elected Brian Mulroney. By this stan- dard, William Lyon Mackenzie King DONE WRONG? easily turned out to be our best prime minister. In 1921, he inherited a Desmond Morton deeply divided country, a treasury near ruin because of over-expansion of rail- ways, and an economy gripped by a brutal depression. By 1948, Canada had emerged unscathed, enriched and almost undivided from the war into spent last summer’s dismal August Canadian Pension Commission. In a the durable prosperity that bred our revising a book called A Short few days of nimble invention, Bennett Baby Boom generation. Who cared if I History of Canada and staring rescued veterans’ benefits from 15 King had halitosis and a professorial across Lake Memphrémagog at the years of political logrolling and talent for boring audiences? astonishing architecture of the Abbaye launched a half century of relatively St-Benoît. Brief as it is, the Short History just and generous dealing. Did anyone ll of which is a lengthy prelude to tries to cover the whole 12,000 years of notice? Do similar achievements lie to A passing premature and imperfect Canadian history but, since most buy- the credit of Jean Chrétien or, for that judgement on Jean Chrétien. Using ers prefer their own life’s history to a matter, Brian Mulroney or Pierre Elliott the same criteria that put King first more extensive past, Jean Chrétien’s Trudeau? Dependent on the media, and Trudeau deep in the pack, where last seven years will get about as much the Opposition and government prop- does Chrétien stand? In 1993, most space as the First Nations’ first dozen aganda, what do I know? Do I refuse to Canadians were still caught in the millennia. -

Tuesday, May 2, 2000

CANADA 2nd SESSION • 36th PARLIAMENT • VOLUME 138 • NUMBER 50 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, May 2, 2000 THE HONOURABLE ROSE-MARIE LOSIER-COOL SPEAKER PRO TEMPORE This issue contains the latest listing of Senators, Officers of the Senate, the Ministry, and Senators serving on Standing, Special and Joint Committees. CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1170 THE SENATE Tuesday, May 2, 2000 The Senate met at 2:00 p.m., the Speaker pro tempore in the Last week, Richard Donahoe joined this political pantheon and Chair. there he belongs, now part of the proud political history and tradition of Nova Scotia. He was a greatly gifted and greatly respected public man. He was much beloved, especially by the Prayers. rank and file of the Progressive Conservative Party. Personally, and from my earliest days as a political partisan, I recall his kindness, thoughtfulness and encouragement to me and to others. THE LATE HONOURABLE Dick was an inspiration to several generations of young RICHARD A. DONAHOE, Q.C. Progressive Conservatives in Nova Scotia. • (1410) TRIBUTES The funeral service was, as they say nowadays, quite “upbeat.” Hon. Lowell Murray: Honourable senators, I have the sad It was the mass of the resurrection, the Easter service, really, with duty to record the death, on Tuesday, April 25, of our former great music, including a Celtic harp and the choir from Senator colleague the Honourable Richard A. -

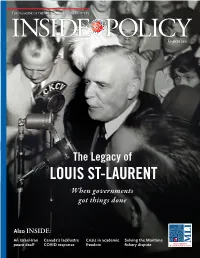

LOUIS ST-LAURENT When Governments Got Things Done

MARCH 2021 The Legacy of LOUIS ST-LAURENT When governments got things done Also INSIDE: An Israel-Iran Canada’s lacklustre Crisis in academic Solving the Maritime peace deal? COVID response freedom fishery dispute 1 PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee LeeBrianby Crowley, Crowley,the Lee Macdonald-Laurier Crowley,Managing Managing Managing Director, Director, Director [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames DeputyAnderson, Anderson, Managing Managing Managing Director, Editor, Editor, Editorial Inside Inside Policy and Policy Operations Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] David McDonough, Deputy Editor James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:Editor, writers: Inside Policy Contributing writers: ThomasThomas S. S.Axworthy Axworthy PastAndrewAndrew contributors Griffith Griffith BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. Axworthy Andrew Griffith Benjamin Perrin Mary-Jane BennettDonaldDonald Barry Barry Jeremy DepowStanleyStanley H. H. Hartt HarttMarcus Kolga MikeMike J.Priaro Berkshire Priaro Miller Massimo BergaminiDonald Barry Peter DeVries Stanley H. HarttAudrey Laporte Mike Priaro Jack Mintz Derek BurneyKenKen Coates Coates Brian Dijkema PaulPaul Kennedy KennedyBrad Lavigne ColinColin RobertsonRobert Robertson P. Murphy Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson Charles Burton Ujjal Dosanjh Ian Lee Dwight Newman BrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley Crowley AudreyAudrey Laporte Laporte RogerRoger Robinson Robinson Catherine -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 3rd SESSION . 37th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 141 . NUMBER 6 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, February 11, 2004 ^ THE HONOURABLE DAN HAYS SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Communication Canada ± Canadian Government Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 112 THE SENATE Wednesday, February 11, 2004 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. I had the privilege and great pleasure of knowing Robert Stanfield for many years. His warmth and folksiness were Prayers. legendary, as was the huge, compassionate heart of this independently wealthy Red Tory. SENATORS' STATEMENTS Today I want to reflect on the late Dalton Camp's oft-quoted comment that Robert Stanfield ``may be too good for politics.'' TRIBUTES That reflection was, with the greatest respect to Dalton, inaccurate. THE LATE RIGHT HONOURABLE ROBERT L. STANFIELD, P.C., Q.C. Tough-minded, disciplined and possessed of remarkable intellectual flexibility, the man who became an icon in my The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I wish to advise province brought civility, honour and a new respect for the that I have received, pursuant to our rules, a letter from the political playing field, yet he was also a gifted tactician and a Honourable Senator Lynch-Staunton, Leader of the Opposition masterful strategist in battle. There is a great deal of credence in in the Senate, requesting that we provide for time this afternoon the very worthy observation that Robert Stanfield bore a for tributes to the Right Honourable Robert L. -

The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy

51 The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy Yan Campagnolo* La légitimité politique du secret ministériel La legitimidad política del secreto ministerial A legitimidade política do segredo ministerial 内阁机密的政治正当性 Résumé Abstract Dans le système de gouvernement In the Westminster system of re- responsable de type Westminster, les sponsible government, constitutional conventions constitutionnelles protègent conventions have traditionally safe- traditionnellement le secret des délibéra- guarded the secrecy of Cabinet proceed- tions du Cabinet. Dans l’ère moderne, où ings. In the modern era, where openness l’ouverture et la transparence sont deve- and transparency have become funda- nues des valeurs fondamentales, le secret mental values, Cabinet secrecy is now ministériel est désormais perçu avec scep- looked upon with suspicion. The justifi- ticisme. La justification et la portée de la cation and scope of Cabinet secrecy re- règle font l’objet de controverses. Cet ar- main contentious. The aim of this article ticle aborde ce problème en expliquant les is to address this problem by explaining raisons pour lesquelles le secret ministériel why Cabinet secrecy is, within limits, es- est, à l’intérieur de certaines limites, essen- sential to the proper functioning of our tiel au bon fonctionnement de notre sys- system of government. Based on the rele- * Assistant Professor, Common Law Section, University of Ottawa. This article is based on the first chapter of a dissertation which was submitted in connection with fulfilling the requirements for a doctoral degree in law at the University of Toronto. The research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. For helpful comments on earlier versions, I am indebted to Kent Roach, David Dyzenhaus, Hamish Stewart, Peter Oliver and the anonymous reviewers of the Revue juridique Thémis. -

History and the Tourist Gaze: the Politics of Commemoration in Nova Scotia, 1935-1964

IAN McKAY History and the Tourist Gaze: The Politics of Commemoration in Nova Scotia, 1935-1964 IN JUNE 1961 WILL R. BIRD sounded like a man besieged. Never since becoming chairman of the Historic Sites Advisory Council in 1949 had he been busier. Every day brought phone calls, visits, meetings. Activists in Parrsboro wanted a plaque for the site of the first "air mail" flight; Bird was doubtful, and suggested they reconstruct a nearby blockhouse instead. In Joggins he conferred with "some of the leading citizens" about honouring "King" Seaman, a legendary entrepreneur; in Amherst, he promised the tourist committee of the board of trade that plaques would be coming in the next year; requests rolled in from Yarmouth and Shelburne, Baddeck and Milton, Sherbrooke and Port Wallis, Marble Mountain and the Ovens: he found it overwhelming. "It is little more than six weeks since our Annual Meeting", he exclaimed in a letter to Premier Robert Stanfield, "and already I have half an agenda for May 1962. I have spoken at ten widely different meetings this spring and all want the same topic — historic Nova Scotia. History has become almost a mania in some communities, who feel they can attract tourists if their history is made known".1 Bird's description has a contemporary ring. One aspect of our present condition of postmodernity — that is, the experience of a capitalist modernity transformed by globalization, cybernetics and the fragmentation of most traditional systems of meaning — is the "mode retro". Images of the past are used to promote everything from political parties to breakfast cereals: this "flourishing" of the past appears as an immense catalogue of arresting images. -

Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968

Nova Britannia Revisited: Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968 C. P. Champion Department of History McGill University, Montreal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History February 2007 © Christian Paul Champion, 2007 Table of Contents Dedication ……………………………….……….………………..………….…..2 Abstract / Résumé ………….……..……….……….…….…...……..………..….3 Acknowledgements……………………….….……………...………..….…..……5 Obiter Dicta….……………………………………….………..…..…..….……….6 Introduction …………………………………………….………..…...…..….….. 7 Chapter 1 Canadianism and Britishness in the Historiography..….…..………….33 Chapter 2 The Challenge of Anglo-Canadian ethnicity …..……..…….……….. 62 Chapter 3 Multiple Identities, Britishness, and Anglo-Canadianism ……….… 109 Chapter 4 Religion and War in Anglo-Canadian Identity Formation..…..……. 139 Chapter 5 The celebrated rite-de-passage at Oxford University …….…...…… 171 Chapter 6 The courtship and apprenticeship of non-Wasp ethnic groups….….. 202 Chapter 7 The “Canadian flag” debate of 1964-65………………………..…… 243 Chapter 8 Unification of the Canadian armed forces in 1966-68……..….……. 291 Conclusions: Diversity and continuity……..…………………………….…….. 335 Bibliography …………………………………………………………….………347 Index……………………………………………………………………………...384 1 For Helena-Maria, Crispin, and Philippa 2 Abstract The confrontation with Britishness in Canada in the mid-1960s is being revisited by scholars as a turning point in how the Canadian state was imagined and constructed. During what the present thesis calls the “crisis of Britishness” from 1964 to 1968, the British character of Canada was redefined and Britishness portrayed as something foreign or “other.” This post-British conception of Canada has been buttressed by historians depicting the British connection as a colonial hangover, an externally-derived, narrowly ethnic, nostalgic, or retardant force. However, Britishness, as a unique amalgam of hybrid identities in the Canadian context, in fact took on new and multiple meanings.