Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terms of Office

Terms of Office The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, 1 July 1867 - 5 November 1873, 17 October 1878 - 6 June 1891 The Right Honourable The Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald Alexander Mackenzie (1815-1891) (1822-1892) The Honourable Alexander Mackenzie, 7 November 1873 - 8 October 1878 The Honourable Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott, 16 June 1891 - 24 November 1892 The Right Honourable The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir John Joseph Sir John Sparrow Sir John Sparrow David Thompson, Caldwell Abbott David Thompson 5 December 1892 - 12 December 1894 (1821-1893) (1845-1894) The Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell, 21 December 1894 - 27 April 1896 The Right Honourable Sir Charles Tupper, 1 May 1896 - 8 July 1896 The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell Sir Charles Tupper The Right Honourable (1823-1917) (1821-1915) Sir Wilfrid Laurier, 11 July 1896 - 6 October 1911 The Right Honourable Sir Robert Laird Borden, 10 October 1911 - 10 July 1920 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen, Sir Wilfrid Laurier Sir Robert Laird Borden (1841-1919) (1854-1937) 10 July 1920 - 29 December 1921, 29 June 1926 - 25 September 1926 The Right Honourable William Lyon Mackenzie King, 29 December 1921 - 28 June 1926, 25 September 1926 - 7 August 1930, 23 October 1935 - 15 November 1948 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen William Lyon Richard Bedford Bennett, (1874-1960) Mackenzie King (later Viscount), (1874-1950) 7 August 1930 - 23 October 1935 The Right Honourable Louis Stephen St. Laurent, 15 November 1948 - 21 June 1957 The Right Honourable John George Diefenbaker, The Right Honourable The Right Honourable 21 June 1957 - 22 April 1963 Richard Bedford Bennett Louis Stephen St. -

The Long Reach of War: Canadian Records Management and the Public Archives

The Long Reach of War: Canadian Records Management and the Public Archives by Kathryn Rose A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Kathryn Rose 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis explores why the Public Archives of Canada, which was established in 1872, did not have the full authority or capability to collect the government records of Canada until 1966. The Archives started as an institution focused on collecting historical records, and for decades was largely indifferent to protecting government records. Royal Commissions, particularly those that reported in 1914 and 1962 played a central role in identifying the problems of records management within the growing Canadian civil service. Changing notions of archival theory were also important, as was the influence of professional academics, particularly those historians mandated to write official wartime histories of various federal departments. This thesis argues that the Second World War and the Cold War finally motivated politicians and bureaucrats to address records concerns that senior government officials had first identified during the time of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Geoffrey Hayes, for his enthusiasm, honesty and dedication to this process. I am grateful for all that he has done. -

A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLIII, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2016) “A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65 Greg Donaghy1 2014-15 marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian- Hungarian diplomatic relations. On January 14, 1965, under cold blue skies and a bright sun, János Bartha, a 37-year-old expert on North Ameri- can affairs, arrived in the cozy, wood paneled offices of the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Paul Martin Sr. As deputy foreign minister Marcel Cadieux and a handful of diplomats looked on, Bartha presented his credentials as Budapest’s first full-time representative in Canada. Four months later, on May 18, Canada’s ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Mal- colm Bow, arrived in Budapest to present his credentials as Canada’s first non-resident representative to Hungary. As he alighted from his embassy car, battered and dented from an accident en route, with its fender flag already frayed, grey skies poured rain. The contrasting settings in Ottawa and Budapest are an apt meta- phor for this uneven and often distant relationship. For Hungary, Bartha’s arrival was a victory to savor, the culmination of fifteen years of diplo- matic campaigning and another step out from beneath the shadows of the postwar communist take-over and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. For Canada, the benefits were much less clear-cut. In the context of the bitter East-West Cold War confrontation, closer ties with communist Hungary demanded a steep domestic political price in exchange for a bundle of un- certain economic, consular, and political gains. -

A Tribute to the Honourable R. Gordon Robertson, P.C., C.C., LL.D., F.R.S.C., D.C.L

A Tribute to The Honourable R. Gordon Robertson, P.C., C.C., LL.D., F.R.S.C., D.C.L. By Thomas d’Aquino MacKay United Church Ottawa January 21, 2013 Reverend Doctor Montgomery; members of the Robertson family; Joan - Gordon’s dear companion; Your Excellency; Madam Chief Justice; friends, I am honoured – and humbled – to stand before you today, at Gordon’s request, to pay tribute to him and to celebrate with you his remarkable life. He wished this occasion to be one, not of sadness, but of celebration of a long life, well lived, a life marked by devotion to family and to country. Gordon Robertson – a good, fair, principled, and ever so courteous man - was a modest person. But we here today know that he was a giant. Indeed, he has been described as his generation’s most distinguished public servant – and what a generation that was! Gordon was proud of his Saskatchewan roots. Born in 1917 in Davidson – a town of 300 “on the baldest prairie”, in Gordon’s words, he thrived under the affection of his Norwegian-American mother and grandparents. He met his father – of Scottish ancestry - for the first time at the age of two, when he returned home after convalescing from serious wounds suffered at the epic Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge. He was, by Gordon’s account, a stern disciplinarian who demanded much of his son in his studies, in pursuit of manly sports, and in his comportment. Gordon did not disappoint. He worked his way through drought- and depression-torn Saskatchewan, attended Regina College and the University of Saskatchewan, and in 1938 was on his way to Oxford University, a fresh young Rhodes Scholar. -

Circular No. 5^ ^

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION, NANAIMO, B.C. Circular No. 5^ ^ LISTS OF TITLES OF PUBLICATIONS of the FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA 1955-1960 Prepared by R. L0 Maclntyre Office of the Chairman, Ottawa March, 1961 FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION, NANAIMO, B.C. If Circular No. 5# LISTS OF TITLES OF PUBLICATIONS of the FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA 1955-1960 Prepared by R. L, Maclntyre Office of the Chairman, Ottawa March, 1961 FOREWORD This list has been prepared to fill a need for an up-to-date listing of publications issued by the Fisheries Research Board since 1954. A comprehensive "Index and list of titles, publications of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 1901-1954" is available from the Queen's Printer, Ottawa, at 75 cents per copy. A new printed index and list of titles similar to the above Bulletin (No. 110) is planned for a few years hence. This will incorporate the publications listed herein, plus those issued up to the time the new Bulletin appears. All of the publications listed here may be pur chased from the Queen's Printer at the prices shown, with the exception of the Studies Series (yearly bindings of reprints of papers by Board staff which are published in outside journals). A separate of a paper shown listed under "Journal" or "Studies Series" may be obtained from the author or issuing establishment, if copies are still available. In addition to the publications listed, various *-,* Board establishments put out their own series of V Circulars. Enquiries concerning such processed material should be addressed to the Director of the Station con cerned. -

Recognition Report SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 THROUGH AUGUST 31, 2019

FY 2019 Recognition Report SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 THROUGH AUGUST 31, 2019 The University of Texas School of Law FY 2019 Recognition Report CONTENTS 2 Giving Societies Letter from the Dean 9 A Year in Numbers We’ve just completed another remarkable annual giving drive 11 Participation by Class Year at the law school. Here you will find our roster of devoted 34 Longhorn Loyal supporters who participated in the 2018-19 campaign. They are 47 Sustaining Scholars our heroes. 48 100% Giving Challenge The distinctive mission and historical hallmark of our law school is to provide a top-tier education to our students without 49 Planned Giving top-tier debt. Historically, we have done it better than anyone. 50 Women of Texas Law You all know it well; I’ll bet most of you would agree that 51 Texas Law Reunion 2020 coming to the School of Law was one of the best decisions you ever made. The value and importance of our mission is shown in the lives you lead. This Recognition Report honors the This great mission depends on support from all of our alumni. alumni and friends who gave generously I hope that if you’re not on the report for the year just ended, to The University of Texas School of Law you’ll consider this an invitation to be one of the first to get on from September 1, 2018 to August 31, next year’s list! 2019. We sincerely thank the individuals and organizations listed herein. They help Please help us to keep your school great. -

1866 (C) Circa 1510 (A) 1863

BONUS : Paintings together with their year of completion. (A) 1863 (B) 1866 (C) circa 1510 Vancouver Estival Trivia Open, 2012, FARSIDE team BONUS : Federal cabinet ministers, 1940 to 1990 (A) (B) (C) (D) Norman Rogers James Ralston Ernest Lapointe Joseph-Enoil Michaud James Ralston Mackenzie King James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent 1940s Andrew McNaughton 1940s Douglas Abbott Louis St. Laurent James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent Brooke Claxton Douglas Abbott Lester Pearson Stuart Garson 1950s 1950s Ralph Campney Walter Harris John Diefenbaker George Pearkes Sidney Smith Davie Fulton Donald Fleming Douglas Harkness Howard Green Donald Fleming George Nowlan Gordon Churchill Lionel Chevrier Guy Favreau Walter Gordon 1960s Paul Hellyer 1960s Paul Martin Lucien Cardin Mitchell Sharp Pierre Trudeau Leo Cadieux John Turner Edgar Benson Donald Macdonald Mitchell Sharp Edgar Benson Otto Lang John Turner James Richardson 1970s Allan MacEachen 1970s Ron Basford Donald Macdonald Don Jamieson Barney Danson Otto Lang Jean Chretien Allan McKinnon Flora MacDonald JacquesMarc Lalonde Flynn John Crosbie Gilles Lamontagne Mark MacGuigan Jean Chretien Allan MacEachen JeanJacques Blais Allan MacEachen Mark MacGuigan Marc Lalonde Robert Coates Jean Chretien Donald Johnston 1980s Erik Nielsen John Crosbie 1980s Perrin Beatty Joe Clark Ray Hnatyshyn Michael Wilson Bill McKnight Doug Lewis BONUS : Name these plays by Oscar Wilde, for 10 points each. You have 30 seconds. (A) THE PAGE OF HERODIAS: Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman. You would fancy she was looking for dead things. THE YOUNG SYRIAN: She has a strange look. -

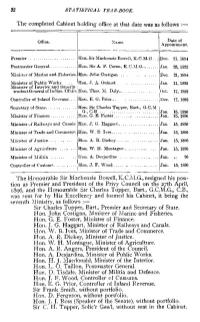

The Completed Cabinet Holding Office at That Date Was As Follows The

32 STATISTICAL YEARBOOK. The completed Cabinet holding office at that date was as follows Office. Date of Name. Appointment. Premier Hon. Sir Mackenzie Bowell, K.C.M.G. Dec. 21, 1894 Postmaster General Hon. Sir A. P. Caron, K.C.M.G Jan. 25, 1892 Minister of Marine and Fisheries. Hon. John Costigan Dec. 21, 1894 Minister of Public Works Hon. J. A. Ouimet Jan. 11, 1892 Minister of Interior and Superin tendent General of Indian Affairs Hon. Thos. M. Daly Oct. 17, 1892 Controller of Inland Revenue.... Hon. E. G. Prior Dec. 17, 1895 Secretary of State Hon. Sir Charles Tupper, Bart., G.C.M G., C.B Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Finance Hon. G.E.Foster Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Railways and Canals. Hon. J. G. Haggart Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Trade and Commerce. Hon. W. B. Ives Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Justice Hon. A. R.Dickey Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Agriculture Hon. W. H. Montague . Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Militia Hon. A. Desjardins .. Jan. .; 96 Controller of Custom0 Hon. J. F. Wood Jan. 15, 1896 The Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell, K.C.M.G., resigned his posi tion as Premier and President of the Privy Council on the 27th April, 1S96, and the Honourable Sir Charles Tupper, Bart., G.C.M.G., C.B., was sent for by His Excellency and formed his Cabinet, it being the seventh Ministry, as follows :— Sir Charles Tupper, Bart., Premier and Secretary of State. Hon. John Costigan, Minister of Marine and Fisheries. Hon. G. E. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

Money Just In.

i HE GLE V » VOL. IV. ALEXANDRIA, ONT., FRIDAY, JANUARY 17, 1896. NO. 51.^ M)TIC i:. visited .'rieiid.'? at Laggau last Friday even- MAXVILLE Endeavor principles, ladies and gentlemen Miss Ross, of McCormick, left 4L. L. McDOJS^ALD, M. D. ing. W. J. McCart, of Avonmorc, was in town taking part. } Creek on Saturday, where she pw dlcttgarn) ^tos. Mr. Archie Munro, of South Indian, llClI of those I. nUed jMr. A. Grant was in Alo.xaiulria. on on Thursday. spending some days with relatives. ALEXANDRIA, ONT. agent for potatoes was canvassing in town —la PCBLI8BEI>— DOORS, Crnii-t l[<ni'=c Covmvall, on Saturday. D. P. McDougall spent Friday in Mon- Office acd residence—Comer Of Main and Ttu'.-(lav.‘2Sth .Ii irv..\.l).,J::‘:i.Àat.-2p.m., pur- I)f. McDerniid, of k'ankleck lliil. was in on Tuesday. A Mr. Donald McPhec, son of Cou’ / EVERY FRIDAY MORNIK 0» Elgin Streets. sua'it to stiituti- town last Wednesday. ?.Iiss Maud McLaughlin, of Montreal, is Miss Aird, of Sandringham, is engaged D. D. McPhec, left on Monday- —AT THE— vrtl). ]b!iih as teacher in the school at the east end. Sash, Frames, WDKl.W I. M VCDONKLE. Our boys arc talking of getting up a the guest of Mrs. A. H. Edwards. resume bis studies at tho JesuiL . QLENOARRY “NEWS" PRINTING OFFICE Gouiif V Clerk, D. A ( lacrosse team next season, if such bo tlie Jas. G. Howdeu, of Montreal, was in A number from this vicinity attended MAIN STREET. ALEXANDRIA. ONT case, some of the older tcants around will town on Monday Rev. -

Prime Ministers and Government Spending: a Retrospective by Jason Clemens and Milagros Palacios

FRASER RESEARCH BULLETIN May 2017 Prime Ministers and Government Spending: A Retrospective by Jason Clemens and Milagros Palacios Summary however, is largely explained by the rapid drop in expenditures following World War I. This essay measures the level of per-person Among post-World War II prime ministers, program spending undertaken annually by each Louis St. Laurent oversaw the largest annual prime minister, adjusting for inflation, since average increase in per-person spending (7.0%), 1870. 1867 to 1869 were excluded due to a lack though this spending was partly influenced by of inflation data. the Korean War. Per-person spending spiked during World Our current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, War I (under Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden) has the third-highest average annual per-per- but essentially returned to pre-war levels once son spending increases (5.2%). This is almost the war ended. The same is not true of World a full percentage point higher than his father, War II (William Lyon Mackenzie King). Per- Pierre E. Trudeau, who recorded average an- person spending stabilized at a permanently nual increases of 4.5%. higher level after the end of that war. Prime Minister Joe Clark holds the record The highest single year of per-person spend- for the largest average annual post-World ing ($8,375) between 1870 and 2017 was in the War II decline in per-person spending (4.8%), 2009 recession under Prime Minister Harper. though his tenure was less than a year. Prime Minister Arthur Meighen (1920 – 1921) Both Prime Ministers Brian Mulroney and recorded the largest average annual decline Jean Chretien recorded average annual per- in per-person spending (-23.1%). -

An Immigrant Story Scotland to Canada

An Immigrant Story Scotland to Canada John McIntosh (1865 – 1925) Henrietta Calder (1867 – 1950) Circa 1908 2 Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Comments about the Sources ......................................................................................................... 4 1 A bit of Scottish History ............................................................................................................. 6 2 Scottish Highland Clans .......................................................................................................... 10 3 John McIntosh; his parents and ancestors .............................................................................. 12 His Father’s Side ................................................................................................. 12 His Mother’s Side ................................................................................................ 13 4 Henrietta Calder, her parents and ancestors .......................................................................... 15 Her Father’s Side ................................................................................................. 15 Her Mother’s Side ................................................................................................ 19 Brinmore .............................................................................................................. 20 5 John and Henrietta (Harriet)