Master Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COIN in Afghanistan - Winning the Battles, Losing the War?

COIN in Afghanistan - Winning the Battles, Losing the War? MAGNUS NORELL FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency, is a mainly assignment-funded agency under the Ministry of Defence. The core activities are research, method and technology development, as well as studies conducted in the interests of Swedish defence and the safety and security of society. The organisation employs approximately 1000 personnel of whom about 800 are scientists. This makes FOI Sweden’s largest research institute. FOI gives its customers access to leading-edge expertise in a large number of fields such as security policy studies, defence and security related analyses, the assessment of various types of threat, systems for control and management of crises, protection against and management of hazardous substances, IT security and the potential offered by new sensors. FOI Swedish Defence Research Agency Phone: +46 8 555 030 00 www.foi.se FOI Memo 3123 Memo Defence Analysis Defence Analysis Fax: +46 8 555 031 00 ISSN 1650-1942 March 2010 SE-164 90 Stockholm Magnus Norell COIN in Afghanistan - Winning the Battles, Losing the War? “If you don’t know where you’re going. Any road will take you there” (From a song by George Harrison) FOI Memo 3123 Title COIN in Afghanistan – Winning the Battles, Losing the War? Rapportnr/Report no FOI Memo 3123 Rapporttyp/Report Type FOI Memo Månad/Month Mars/March Utgivningsår/Year 2010 Antal sidor/Pages 41 p ISSN ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet Projektnr/Project no A12004 Godkänd av/Approved by Eva Mittermaier FOI, Totalförsvarets Forskningsinstitut FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency Avdelningen för Försvarsanalys Department of Defence Analysis 164 90 Stockholm SE-164 90 Stockholm FOI Memo 3123 Programme managers remarks The Asia Security Studies programme at the Swedish Defence Research Agency’s Department of Defence Analysis conducts research and policy relevant analysis on defence and security related issues. -

Conflict in Afghanistan I

Conflict in Afghanistan I 92 Number 880 December 2010 Volume Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Part 1: Socio-political and humanitarian environment Interview with Dr Sima Samar Chairperson of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission Afghanistan: an historical and geographical appraisal William Maley Dynamic interplay between religion and armed conflict in Afghanistan Ken Guest Transnational Islamic networks Imtiaz Gul Impunity and insurgency: a deadly combination in Afghanistan Norah Niland The right to counsel as a safeguard of justice in Afghanistan: the contribution of the International Legal Foundation Jennifer Smith, Natalie Rea, and Shabir Ahmad Kamawal State-building in Afghanistan: a case showing the limits? Lucy Morgan Edwards The future of Afghanistan: an Afghan responsibility Conflict I in Afghanistan Taiba Rahim Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action www.icrc.org/eng/review Conflict in Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal web site at: ISSN 1816-3831 http://www.journals.cambridge.org/irc Afghanistan I Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief: Vincent Bernard The Review is printed in English and is Editorial assistant: Michael Siegrist published four times a year, in March, Publication assistant: June, September and December. Claire Franc Abbas Annual selections of articles are also International Review of the Red Cross published on a regional level in Arabic, Aim and scope 19, Avenue de la Paix Chinese, French, Russian and Spanish. The International Review of the Red Cross is a periodical CH - 1202 Geneva, Switzerland published by the ICRC. Its aim is to promote reflection on t +41 22 734 60 01 Published in association with humanitarian law, policy and action in armed conflict and f +41 22 733 20 57 Cambridge University Press. -

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-Geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence John O’Loughlin, Frank D. W. Witmer, and Andrew M. Linke1 Abstract: A team of political geographers analyzes over 5,000 violent events collected from media reports for the Afghanistan and Pakistan conflicts during 2008 and 2009. The violent events are geocoded to precise locations and the authors employ an exploratory spatial data analysis approach to examine the recent dynamics of the wars. By mapping the violence and examining its temporal dimensions, the authors explain its diffusion from traditional foci along the border between the two countries. While violence is still overwhelmingly concentrated in the Pashtun regions in both countries, recent policy shifts by the American and Pakistani gov- ernments in the conduct of the war are reflected in a sizeable increase in overall violence and its geographic spread to key cities. The authors identify and map the clusters (hotspots) of con- flict where the violence is significantly higher than expected and examine their shifts over the two-year period. Special attention is paid to the targeting strategy of drone missile strikes and the increase in their number and geographic extent by the Obama administration. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: H560, H770, O180. 15 figures, 1 table, 113 ref- erences. Key words: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Taliban, Al- Qaeda, insurgency, Islamic terrorism, U.S. military, International Security Assistance Forces, Durand Line, Tribal Areas, Northwest Frontier Province, ACLED, NATO. merica’s “longest war” is now (August 2010) nearing its ninth anniversary. It was Alaunched in October 2001 as a “war of necessity” (Barack Obama, August 17, 2009) to remove the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, and thus remove the support of this regime for Al-Qaeda, the terrorist organization that carried out the September 2001 attacks in the United States. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

Troops in Afghanistan: by Louisa Brooke-Holland July 2018 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 08292, 13 July 2018 Troops in Afghanistan: By Louisa Brooke-Holland July 2018 update Approximately 650 UK armed forces personnel are currently deployed in Afghanistan. The Government announced in July 2018 it will deploy an additional 440 troops, bringing the UK total deployment to 1,100 personnel by early 2019. They are part of NATO’s Resolute Support mission to train, advise and assist the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) and institutions. UK personnel are deployed in non-combat roles, principally at the Afghan National Army Officer Academy, protecting coalition and diplomatic personnel and supporting Afghan security forces in the capital. NATO has increased troop numbers since the Resolute Support mission began in January 2015. It currently stands at just over 16,000 troops from 39 nations (the addition of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates will bring this total up to 41). The security situation remains ‘highly unstable’. The UN reported over 10,000 civilian casualties in 2017, over half of which were attributed to the Taliban. Complex and suicide attacks are a leading cause of civilian casualties. The US has significantly increased the number of airstrikes since President Trump unveiled a new South Asia Strategy last August, releasing more weapons in 2017 than in any year since 2012. Library Briefing paper Afghanistan 2017 examines the political situation. This note focuses on UK deployments since 2015. A new role for NATO Between August 2003 and December 2014 NATO led the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. ISAF was wound up on 31 December 2014, although combat operations formally ended for UK forces two months earlier, in October. -

The Coils of the Anaconda: America's

THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN BY C2009 Lester W. Grau Submitted to the graduate degree program in Military History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date defended: April 27, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Lester W. Grau certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN Committee: ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date approved: April 27, 2009 ii PREFACE Generals have often been reproached with preparing for the last war instead of for the next–an easy gibe when their fellow-countrymen and their political leaders, too frequently, have prepared for no war at all. Preparation for war is an expensive, burdensome business, yet there is one important part of it that costs little–study. However changed and strange the new conditions of war may be, not only generals, but politicians and ordinary citizens, may find there is much to be learned from the past that can be applied to the future and, in their search for it, that some campaigns have more than others foreshadowed the coming pattern of modern war.1 — Field Marshall Viscount William Slim. -

The Taliban's Survival

Global-Local Interactions: Journal of International Relations http://ejournal.umm.ac.id/index.php/GLI/index ISSN: 2657-0009 Vol. 1, No. 2, July 2020, Pp. 38-46 THE TALIBAN'S SURVIVAL: FROM POST-2001 INSURGENCY TO 2020 PEACE DEAL WITH THE UNITED STATES Taufiq -E- Faruque Department of International Relations, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh Article Info Abstract Article history: The 2020 United States (US)-Taliban peace deal has essentially made the Received August 18, 2020 Taliban movement as one of the most durable and resilient insurgent groups in Revised November 26, 2020 today's world. Following the 'levels of analysis' of international relations as an Accepted December 04, 2020 analytical framework, this paper explores the reasons behind the survival of the Available online December 12, 2020 Taliban insurgency in an integrative framework that organizes the individual and group, state, and international level dynamics of this insurgency in a single Cite: account. The paper argues that the defection of politically and economically Faruque, Taufiq -E-. (2020). The Taliban’s marginalized individual Afghans, the multilayered and horizontal structure of the Survival: From Post-2001 Insurgency to 2020 Taliban insurgency, regional power configuration in South Asia, and the lack of Peace Deal with The United States. Global- a coherent post-invasion strategy of the US and its allies factored into the Local Interaction: Journal of International survival of the Taliban insurgency that resulted in a peace deal between the Relations, 1(2). Taliban and the US. * Corresponding author. Keywords: Taliban, Afghanistan, insurgency, United States, peace deal Taufiq -E- Faruque E-mail address: [email protected] Introduction It was hard to imagine that the Taliban would be able to mount a resilient challenge to a large-scale commitment of forces by the US and its allies. -

The Evolution of the Taliban

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2008-06 The evolution of the Taliban Samples, Christopher A. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/4101 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE EVOLUTION OF THE TALIBAN by Shahid A. Afsar Christopher A. Samples June 2008 Thesis Advisor: Thomas H. Johnson Second Reader: Heather S. Gregg Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE The Evolution of the Taliban 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHORS Shahid A. Afsar and Christopher A. Samples 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING N/A AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. -

Desider: Issue 98, August 2016

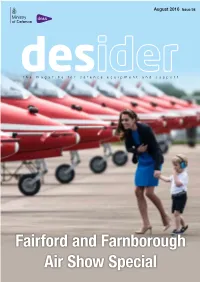

August 2016 Issue 98 desthe magazine for defence equipment and support Fairford and Farnborough Air Show Special B:216 mm T:210 mm S:186 mm THE VALUE OF WORKING TOGETHER TO B:303 mm S:266 mm DELIVER LEADING T:297 mm EDGE CAPABILITY. In a world where our threats need coalitions to defeat them, so too do we need partnerships between nations and companies to develop battle-winning capability. Northrop Grumman has over 2,200 staff across eleven European nations and key roles in delivering critical capabilities such as NATO AGS, F-35, Sentry AWACS, land-based and airborne radars, laser-based aircraft infrared countermeasures, QE Class aircraft carriers, and full-spectrum cyber, as well as developing new technologies to thwart emerging threats. We may not always be visible, but our technology is all pervasive, as is our commitment to build strong European businesses to serve our customers for the long term. ©2015 Northrop Grumman Corporation www.northropgrumman.com/europe 601 West 26th St. Suite 1120 NY, NY 10001 t:646.230.2020 Project Manager: Vanessa Pineda Document Name: NG-INH-Z30663-A_PD1.indd Element: P4CB - standard Current Date: 9-8-2015 12:46 PM Studio Client: Northrop Grumman Bleed: 216 mm w x 303 mm h Prepress: BP Product: INH Trim: 210 mm w x 297 mm h Proof #: 3-RELEASE Proofreader Creative Tracking: NG-INH-Z30663 Safety: 186 mm w x 266 mm h Print Scale: None Page 1 of 1 Print Producer Billing Job: NG-INH-Z29873 Gutter: None InDesign Version: CC Title: UK Brand Ad - Desider Color List: None Art Director Inks: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, -

Poolad Tsiradzho Current

SECRET // 20330125 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE STATES COMMAND HEADQUARTERS , JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO U.S. NAVAL STATION , GUANTANAMO BAY , CUBA APOAE09360 CUBA JTF- GTMO- CDR 25 January2008 MEMORANDUMFORCommander, UnitedStates SouthernCommand, 3511NW 91st Avenue, Miami, FL 33172 SUBJECT: Recommendationfor ContinuedDetentionUnder Control(CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: 000089DP( S) JTF - GTMO Detainee Assessment 1. (S) PersonalInformation: JDIMS/ NDRC ReferenceName: Poolad Tsiradzho Current / True Name and Aliases: Polad Sabir Oglu Sirajov, Abdullah al-Qawgazi Place of Birth: Baku, Azerbaijan (AJ) Date ofBirth: 6 May 1975 Citizenship: Azerbaijan Internment Serial Number ( ISN) -000089DP 2. (U // FOUO Health : Detainee is in overall good health without any significant medical problems. 3. ( U ) JTF- GTMO Assessment : a. (S) Recommendation: JTF-GTMOrecommendsthis detaineefor ContinuedDetention UnderDoDControl(CD) . JTF-GTMOpreviouslyassesseddetaineeas ContinuedDetention on 31 March2007. b . ( / ) Executive Summary: Detainee is assessed to be a member of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) with ties to al-Qaida, the Taliban, and the Azerbaijani-based extremist organization al-Qaida Kavkaz . Detainee’svetting inAfghanistan was directed by 1 AnalystNote: The IMUis a NationalIntelligencePrioritiesFramework( NIPF) counterterrorism( CT) Priority1B target. Priority1Btargetsare defined as terroristgroups, especiallythosewithstatesupport, countriesthat sponsor CLASSIFIED BY : MULTIPLE SOURCES REASON : E.O. 12958, AS AMENDED , SECTION 1.4 ( C DECLASSIFY ON : 20330125 SECRET NOFORN 20330125 SECRET // 20330125 JTF - GTMO -CDR SUBJECT : Recommendation for Continued Detention Under Control (CD) for Guantanamo Detainee , ISN 000089DP (S ) an al-Qaida financier and his name is included on an al-Qaida affiliated document. Detainee participated in hostilities against US and Coalition forces and is assessed to have served as a fighter in Usama Bin Laden's (UBL) 55th Arab Brigade. -

Specially As Well As Those Undertaken by the MERT

PLEASE TAKE YOUR FREE ISSUE 1, 2020 COPY The Nijmegen March 661 Squadron Op CABRIT Celebrating Our LANDING ZONE Reserve Squadrons CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OPERATIONS ACROSS ALL BOUNDARIES LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2019 1 JOURNAL OF THE JOINT HELICOPTER COMMAND TAKE ON A CHALLENGE HIKE. BIKE. CLIMB. RUN. STANDING SIDE Sign up today for: a guaranteed place in the event support from your Regional Fundraiser BY SIDE WITH THE an RAF Benevolent Fund branded top RAF FAMILY FOR a chance to help the RAF Family. OVER 100 YEARS Find out how we help serving and former members of the RAF and their families. rafbf.org/get-involved FREE CALL FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE EMOTIONAL WELLBEING [email protected] 0800169 2942 WELLBEING BREAKS INDEPENDENT LIVING 020 7307 3321 #makeitcount rafbf.org/help FAMILY AND RELATIONSHIPS TRANSITION The RAF Benevolent Fund is a registered charity in England and Wales (1081009) and Scotland (SC038109). CHALLENGE_ADVERT_JAN20 2 LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2020 LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2020 3 FOREWORD LZ CELEBRATING 20 YEARS MEET THE TEAM CONTENTS ISSUE 1 2020 EDITORIAL Editor: Sqn Ldr Joan Ochuodho E: [email protected] JHC HISTORY T: 01264 381178 Operations Across All Boundaries 06 – History Of Joint Helicopter Support SALES Squadron ....................................... 26 elcome to this bumper, Sales Manager: Laurence Rowe 20th Anniversary Royal Air Force Tactical Supply Wing 28 E: [email protected] edition of LZ - I’m sure T: 01536 334218 you will enjoy it. Having HONOURS & AWARDS 06 been an SO2 in the 80th Anniversary Awards Evening 18 – original JHC HQ in 1999, DESIGNER commanded a JHC squadron and a Force, HISTORIC REFLECTIONS Designer: Amanda Robinson W Fixed Wing MAS Transfers to the RAF 21 E: [email protected] and been the 1* Capability Director, I hope I’m reasonably well qualified to pen this Look Back: When Two Become One 30 T: 01536 334226 short introduction. -

Afghanistan Statistics: UK Deaths, Casualties, Mission Costs and Refugees

Research Briefing Number CBP 9298 Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, By Noel Dempsey 16 August 2021 casualties, mission costs and refugees 1 Background Since October 2001, US, UK, and other coalition forces have been conducting military operations in Afghanistan in response to the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. Initially, military action, considered self-defence under the UN Charter, was conducted by a US-led coalition (called Operation Enduring Freedom by the US). NATO invoked its Article V collective defence clause on 12 September 2001. In December 2001, the UN authorised the deployment of a 5,000-strong International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to deploy in, and immediately around, Kabul. This was to provide security and to assist in the reconstruction of the country. While UN mandated, ISAF continued as a coalition effort. US counter terrorism operations under Operation Enduring Freedom remained a distinct parallel effort. In August 2003, NATO took command of ISAF. Over the next decade, and bolstered by a renewed and expanded UN mandate,1 ISAF operations grew 1 UN Security Council Resolution 1510 (2003) commonslibrary.parliament.uk Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, casualties, mission costs and refugees into the whole country and evolved from security and stabilisation, into combat and counterinsurgency operations, and then to transition. Timeline of major foreign force decisions • October 2001: Operation Enduring Freedom begins. • December 2001: UN authorises the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). • August 2003: NATO assumes ISAF command. • June 2006: ISAF mandate expanded. • 2009: Counterinsurgency operations begin. • 2011-2014: Three-year transition to Afghan-led security operations. • October 2014: End of UK combat operations.