Troops in Afghanistan: by Louisa Brooke-Holland July 2018 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desider: Issue 98, August 2016

August 2016 Issue 98 desthe magazine for defence equipment and support Fairford and Farnborough Air Show Special B:216 mm T:210 mm S:186 mm THE VALUE OF WORKING TOGETHER TO B:303 mm S:266 mm DELIVER LEADING T:297 mm EDGE CAPABILITY. In a world where our threats need coalitions to defeat them, so too do we need partnerships between nations and companies to develop battle-winning capability. Northrop Grumman has over 2,200 staff across eleven European nations and key roles in delivering critical capabilities such as NATO AGS, F-35, Sentry AWACS, land-based and airborne radars, laser-based aircraft infrared countermeasures, QE Class aircraft carriers, and full-spectrum cyber, as well as developing new technologies to thwart emerging threats. We may not always be visible, but our technology is all pervasive, as is our commitment to build strong European businesses to serve our customers for the long term. ©2015 Northrop Grumman Corporation www.northropgrumman.com/europe 601 West 26th St. Suite 1120 NY, NY 10001 t:646.230.2020 Project Manager: Vanessa Pineda Document Name: NG-INH-Z30663-A_PD1.indd Element: P4CB - standard Current Date: 9-8-2015 12:46 PM Studio Client: Northrop Grumman Bleed: 216 mm w x 303 mm h Prepress: BP Product: INH Trim: 210 mm w x 297 mm h Proof #: 3-RELEASE Proofreader Creative Tracking: NG-INH-Z30663 Safety: 186 mm w x 266 mm h Print Scale: None Page 1 of 1 Print Producer Billing Job: NG-INH-Z29873 Gutter: None InDesign Version: CC Title: UK Brand Ad - Desider Color List: None Art Director Inks: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, -

Specially As Well As Those Undertaken by the MERT

PLEASE TAKE YOUR FREE ISSUE 1, 2020 COPY The Nijmegen March 661 Squadron Op CABRIT Celebrating Our LANDING ZONE Reserve Squadrons CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OPERATIONS ACROSS ALL BOUNDARIES LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2019 1 JOURNAL OF THE JOINT HELICOPTER COMMAND TAKE ON A CHALLENGE HIKE. BIKE. CLIMB. RUN. STANDING SIDE Sign up today for: a guaranteed place in the event support from your Regional Fundraiser BY SIDE WITH THE an RAF Benevolent Fund branded top RAF FAMILY FOR a chance to help the RAF Family. OVER 100 YEARS Find out how we help serving and former members of the RAF and their families. rafbf.org/get-involved FREE CALL FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE EMOTIONAL WELLBEING [email protected] 0800169 2942 WELLBEING BREAKS INDEPENDENT LIVING 020 7307 3321 #makeitcount rafbf.org/help FAMILY AND RELATIONSHIPS TRANSITION The RAF Benevolent Fund is a registered charity in England and Wales (1081009) and Scotland (SC038109). CHALLENGE_ADVERT_JAN20 2 LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2020 LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2020 3 FOREWORD LZ CELEBRATING 20 YEARS MEET THE TEAM CONTENTS ISSUE 1 2020 EDITORIAL Editor: Sqn Ldr Joan Ochuodho E: [email protected] JHC HISTORY T: 01264 381178 Operations Across All Boundaries 06 – History Of Joint Helicopter Support SALES Squadron ....................................... 26 elcome to this bumper, Sales Manager: Laurence Rowe 20th Anniversary Royal Air Force Tactical Supply Wing 28 E: [email protected] edition of LZ - I’m sure T: 01536 334218 you will enjoy it. Having HONOURS & AWARDS 06 been an SO2 in the 80th Anniversary Awards Evening 18 – original JHC HQ in 1999, DESIGNER commanded a JHC squadron and a Force, HISTORIC REFLECTIONS Designer: Amanda Robinson W Fixed Wing MAS Transfers to the RAF 21 E: [email protected] and been the 1* Capability Director, I hope I’m reasonably well qualified to pen this Look Back: When Two Become One 30 T: 01536 334226 short introduction. -

Afghanistan Statistics: UK Deaths, Casualties, Mission Costs and Refugees

Research Briefing Number CBP 9298 Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, By Noel Dempsey 16 August 2021 casualties, mission costs and refugees 1 Background Since October 2001, US, UK, and other coalition forces have been conducting military operations in Afghanistan in response to the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. Initially, military action, considered self-defence under the UN Charter, was conducted by a US-led coalition (called Operation Enduring Freedom by the US). NATO invoked its Article V collective defence clause on 12 September 2001. In December 2001, the UN authorised the deployment of a 5,000-strong International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to deploy in, and immediately around, Kabul. This was to provide security and to assist in the reconstruction of the country. While UN mandated, ISAF continued as a coalition effort. US counter terrorism operations under Operation Enduring Freedom remained a distinct parallel effort. In August 2003, NATO took command of ISAF. Over the next decade, and bolstered by a renewed and expanded UN mandate,1 ISAF operations grew 1 UN Security Council Resolution 1510 (2003) commonslibrary.parliament.uk Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, casualties, mission costs and refugees into the whole country and evolved from security and stabilisation, into combat and counterinsurgency operations, and then to transition. Timeline of major foreign force decisions • October 2001: Operation Enduring Freedom begins. • December 2001: UN authorises the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). • August 2003: NATO assumes ISAF command. • June 2006: ISAF mandate expanded. • 2009: Counterinsurgency operations begin. • 2011-2014: Three-year transition to Afghan-led security operations. • October 2014: End of UK combat operations. -

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: Army/Sec/16/03/FOI/2017/11467 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk Mr Mike Cox 12 December 2017 [email protected] Dear Mr Cox, Thank you for your email of 13 November in which you requested the following information: Can you please supply the following information regarding recent Roulement Tours : 1. FIRIC (Falkland Islands Roulement Infantry Company) Which companies of which battalions fulfilled their FIRIC commitment: 4.2014 - 10.2014 (between 1 Mercian and 5 Rifles tours) 6.2015 -10.2015 (between 2 Rifles and 1 Welsh Guards tours) 2.2016 - 5.2016 (between 1 Grenadier Guards and 1 Yorkshire tours) 8.2016 - To date (following 4 Para tour) 2. Operation Elgin (Bosnia) Which units have been assigned to this commitment since 1 Scots in 2014. 3. Operation Toral (Afghanistan) If 1 R Anglian tour was Toral 1, what operational name was given to previous commitments by 1 Coldstream Guards and 2 Rifles during the period March 2014 and January 2015. I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm the information in scope of your request is held and is detailed below. 1. Falkland Islands Roulement Infantry Company The following infantry companies conducted the requested FIRIC Tours: Ser Date Battalion Company (a) (b) -

32Nd SIGNAL REGIMENT

The Magazine of The Royal Corps of Signals Corps Formation: 28th June 1920 Corps Motto: Certa Cito Contents On exercise December 2017 Volume 71 No: 6 FEATURES Chrismas Message from the Corps Colonel 2 History of Signalling in 100 Objects 75 2018 Corps Calendar 84 The Last Parade - Junior Leaders Regiment 88 16 1 Sig Regt REGULARS Falkland Islands RSBF 4 News from Training 6 News from Regiments 16 Other Units/Troops 56 Royal Signals Association 80 Last Post 84 Obituaries 85 SPORT/ADVENTURE TRAINING 32 Sig Regt Parachuting 3 42 Exercise HARD RIDE 65 Exercise MERCURY COMPASS 15 66 Exercise DRAGON DIVER IV 67 Exercise NORTHERN INCA UNICORN 68 Exercise WIMBISH DIVER 2 70 Exercise DRAGON MALAYA TAHAN 72 Exercise DRAGON BAHRAIN ADVENTURER 74 Exercise ARCTIC EXPRESS 76 Exercise HIGHLAND EXPRESS 78 64 Sig Sqn at the NMA Service 46 37 Sig Regt Sailing towards Wishing all of our readers a Hvalfjörður Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year Front Cover: SSgt Dan Jones, 226 Sig Sqn, 14 Sig Regt on Exercise DRACO'S SHADOW. Photo by LCpl Pete Dobson, 226 Sig Sqn, 14 Sig Regt. 76 Exercise ARCTIC EXPRESS The Magazine of The Royal Corps of Signals Note from the Editor Welcome to our Christmas edition and the last year in which there will be six editions of the magazine. Over the course of the past year The Wire has undergone some significant changes with the introduction of the Corps branding and articles becoming more image led. We trust these changes have made the magazine more attractive to our readers and made for a less onerous task for those of you who have to collate and submit the Unit content. -

JSP 761, Honours and Awards in the Armed Forces. Part 1

JSP 761 Honours and Awards in the Armed Forces Part 1: Directive JSP 761 Pt 1 (V5.0 Oct 16) Foreword People lie at the heart of operational capability; attracting and retaining the right numbers of capable, motivated individuals to deliver Defence outputs is critical. This is dependent upon maintaining a credible and realistic offer that earns and retains the trust of people in Defence. Part of earning and retaining that trust, and being treated fairly, is a confidence that the rules and regulations that govern our activity are relevant, current, fair and transparent. Please understand, know and use this JSP, to provide that foundation of rules and regulations that will allow that confidence to be built. JSP 761 is the authoritative guide for Honours and Awards in the Armed Services. It gives instructions on the award of Orders, Decorations and Medals and sets out the list of Honours and Awards that may be granted; detailing the nomination and recommendation procedures for each. It also provides information on the qualifying criteria for and permission to wear campaign medals, foreign medals and medals awarded by international organisations. It should be read in conjunction with Queen’s Regulations and DINs which further articulate detailed direction and specific criteria agreed by the Committee on the Grant of Honours, Decorations and Medals [Orders, Decorations and Medals (both gallantry and campaign)] or Foreign and Commonwealth Office [foreign medals and medals awarded by international organisations]. Lieutenant General Richard Nugee Chief of Defence People Defence Authority for People i JSP 761 Pt 1 (V5.0 Oct 16) Preface How to use this JSP 1. -

Service Inquiry Puma XW229, 11 October 2015

OFFICIAL SENSITIVE PART 1.4- ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS Introduction 5 Methodology Accident Factors...... ...... ... ..... ... .... .... ..... .... .. .... ... ... ..... .. ..... ..... ...... ...... ... 5 Human Factors modelling ................................. ....... .. .. ............ ...... ... .. ... .. 6 Available evidence.. ... .......... .. ... ............................. .. ........................... .... 6 Services..... .... ... ... ... ..... .. .. ... ..... .... .. ................................. ... ...... .. ...... ..... 7 Factors considered by the Panel. ... ... .................... .. ............... .. ... ........... .... 8 Background Op TORAL Aviation Detachment . 8 Puma HC Mk2 Life Extension Programme . .. 8 Puma Force development. ........................ .. .... ....... ..................... ... .... ....... 9 Fight-by-Flight. ... ... ... ................. ..... ......... ..... .. ....... ............. ...... ....... 10 Puma Force Op TORAL deployment. .... .... ..... ... .... ... .... ..... .. ............. ... 10 X Flight.... ..... ... ... ...................... ................... ..... ...... .. ..... ... ..... ... ... 10 Environmental Training and Environmental Qualifications . .. 11 Pre-Deployment Training . 11 Reporting.. ..... .. ... .. ........ .... ....................... .... ...... ... .. ...... ..... ...... ... .. 12 Theatre Qualification . 12 Conclusion - Environmental Qualifications, pre-Deployment Training and Theatre Qualifications.. ........................... ... ... ... ...... .. ...... ... ......... -

Afghanistan's Altercation

AFGHANISTAN’S ALTERCATION Media Influence in Western Conflict Interventions By Nicole Dirksen Radboud University Nijmegen Master's programme in Human Geography Conflicts, Territories and Identities 1 2 Abstract Summary in English Is the pen still mightier than the sword in the globalised era of mass communication? To find an answer to this question this thesis looks into the critical decision-making process of international military interventions. The case analysed is the Resolute Support mission in Afghanistan. The decision-making processes from 2013 until 2018 of two contributing nations, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, are analysed. The dynamics of the interrelationship between the policy- maker, the media and the conflict context itself are thoroughly examined and the findings reflect on classical media theories. In the end it is concluded that media did not have a direct influence on the policy-making process, but nonetheless several findings were made about the relationship between media and policy-makers. Moreover, several classical views on media and media influence could not be confirmed in this research. On the contrary, some key assumptions on media coverage in a conflict context did not fit with the reality in Afghanistan. It also became apparent that there were differences between the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Though relatively similar in culture and democratic traditions, their unique aspects in decision-making and media traditions did have their impact on the policy process. This research gives new insight in many aspects of the complicated game between media, conflict and politics. Yet, in the end it must be concluded that sword nor pen won the battle in Afghanistan. -

Quarterly Afghanistan UK Patient Treatment Statistics: 8 October

Quarterly Afghanistan UK Patient Treatment Statistics: RCDM and DMRC Headley Court 8 October 2007 - 30 September 2015 Published 29 October 2015 This report provides statistical information on United Kingdom (UK) Armed Forces and Civilian personnel who have returned to the UK from Op HERRICK and Op TORAL as a result of an injury or illness, who have been treated at the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine (RCDM) and/or the Defence medical Rehabilitation Centre (DMRC). UK Forces were deployed to Afghanistan in support of the United Nations (UN) authorised, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission. Op HERRICK and Op TORAL are the UK operations in Afghanistan that are covered in this report. Key Points and Trends During the period 8 October 2007 to 30 September 2015 the total number of new patients treated at RCDM or DMRC for injuries or illnesses sustained on Operations in Afghanistan was 3,174 and 1,395 respectively. In Quarter 2 2015/16 there were 91 patients from Operations in Afghanistan treated at either RCDM or DMRC (62 were Battle Injuries, 20 were Non Battle Injuries and nine were Natural Causes). There were five new patients who had not previously been treated at RCDM or DMRC for their injury or illness (four Battle Injuries and one Non Battle Injury). The number of UK Armed Forces and Civilian personnel who were receiving treatment for the first time at RCDM or DMRC as a result of an injury or illness sustained on Operations in Afghanistan peaked in July 2009 and July 2010, at 105 and 103 respectively. -

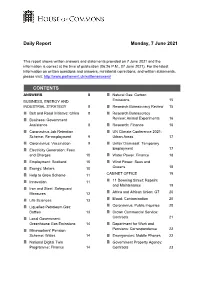

Daily Report Monday, 7 June 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 7 June 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 7 June 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:26 P.M., 07 June 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Natural Gas: Carbon BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Emissions 15 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Research Bureaucracy Review 15 Belt and Road Initiative: China 8 Research Bureaucracy Business: Government Review: Animal Experiments 16 Assistance 8 Research: Finance 16 Coronavirus Job Retention UN Climate Conference 2021: Scheme: Re-employment 9 Urban Areas 17 Coronavirus: Vaccination 9 Unfair Dismissal: Temporary Electricity Generation: Fees Employment 17 and Charges 10 Water Power: Finance 18 Employment: Scotland 10 Wind Power: Seas and Energy: Meters 10 Oceans 18 Help to Grow Scheme 11 CABINET OFFICE 19 Innovation 11 11 Downing Street: Repairs and Maintenance 19 Iron and Steel: Safeguard Measures 12 Africa and African Union: G7 20 Life Sciences 13 Blood: Contamination 20 Liquefied Petroleum Gas: Coronavirus: Public Inquiries 20 Bottles 13 Crown Commercial Service: Local Government: Contracts 21 Greenhouse Gas Emissions 14 Department for Work and Mineworkers' Pension Pensions: Correspondence 22 Scheme: Wales 14 Emergencies: Mobile Phones 22 National Digital Twin Government Property Agency: Programme: Finance 14 Contracts 23 2 Monday, 7 June 2021 Daily Report Press Conferences: Sign Richard -

6 WARFIGHTING at SCALE: REGENERATING and RECONSTITUTING MASS Warfighting at Scale: Regenerating and Reconstituting Mass

The occasional papers of the Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research 6 ARES& ATHENANOVEMBER 2016 What if your country needs How would the British Army of tomorrow? scale up to win a war of national interest? 6 WARFIGHTING AT SCALE: REGENERATING AND RECONSTITUTING MASS Warfighting at scale: Regenerating and reconstituting mass Driven, at least in part, by an imperative to deter resurgent state-based threats to the United Kingdom, the Strategic Defence and Security Review of 2015 (SDSR15) set the British Army on a path towards restoring its readiness to fight wars ‘at scale’ and specifically to regenerate a division at readiness by 2025. This prompted CHACR to embark upon a new line of inquiry, starting with perceived threats and working forwards to the operational realisation of deterrence in practice. The insights from this line of enquiry led us naturally to consider how the British Army could ready itself for the ‘war it might have to fight’. This task fell naturally into two parts: the planned regeneration of divisional-level capability as directed by SDSR15; and the possible need to go further by establishing a plan for reconstituting mass (or mitigating for its absence). Thus a workshop was assigned to each of these subjects, conducted respectively on 23 June and 29 July. This single edition of Ares & Athena brings together a collection of insights from these events and reflections from its participants (military and civilian; serving and retired). As ever, the authors of these inputs are both varied and unspecified. We emphasise that their views in no way represent an official view either from the MOD, British Army or any part thereof. -

2019Flint336215phd.Pdf (1.922Mb)

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2019 Europeanization of Foreign Aid: Managing Post-9/11 Fragile, Conflict-Affected States Flint, James Frank http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/15188 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. EUROPEANIZATION OF FOREIGN AID: MANAGING POST-9/11 FRAGILE, CONFLICT-AFFECTED STATES by JAMES FRANK FLINT A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Law, Criminology and Government 1st April 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION At no time during the registration for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has the author been registered for any other University award without prior agreement of the Doctoral College Quality Sub-Committee. Work submitted for this research degree at the University of Plymouth has not formed part of any other degree either at the University of Plymouth or at another establishment.