Afghanistan's Altercation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

Conflict in Afghanistan I

Conflict in Afghanistan I 92 Number 880 December 2010 Volume Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Part 1: Socio-political and humanitarian environment Interview with Dr Sima Samar Chairperson of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission Afghanistan: an historical and geographical appraisal William Maley Dynamic interplay between religion and armed conflict in Afghanistan Ken Guest Transnational Islamic networks Imtiaz Gul Impunity and insurgency: a deadly combination in Afghanistan Norah Niland The right to counsel as a safeguard of justice in Afghanistan: the contribution of the International Legal Foundation Jennifer Smith, Natalie Rea, and Shabir Ahmad Kamawal State-building in Afghanistan: a case showing the limits? Lucy Morgan Edwards The future of Afghanistan: an Afghan responsibility Conflict I in Afghanistan Taiba Rahim Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action www.icrc.org/eng/review Conflict in Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal web site at: ISSN 1816-3831 http://www.journals.cambridge.org/irc Afghanistan I Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief: Vincent Bernard The Review is printed in English and is Editorial assistant: Michael Siegrist published four times a year, in March, Publication assistant: June, September and December. Claire Franc Abbas Annual selections of articles are also International Review of the Red Cross published on a regional level in Arabic, Aim and scope 19, Avenue de la Paix Chinese, French, Russian and Spanish. The International Review of the Red Cross is a periodical CH - 1202 Geneva, Switzerland published by the ICRC. Its aim is to promote reflection on t +41 22 734 60 01 Published in association with humanitarian law, policy and action in armed conflict and f +41 22 733 20 57 Cambridge University Press. -

Disarmament, Demobilisation, Reintegration in Afghanistan

DIIS REPORT 2006:7 FROM SOLDIER TO CIVILIAN: DISARMAMENT DEMOBILISATION REINTEGRATION IN AFGHANISTAN Peter Dahl Thruelsen DIIS REPORT 2006:7 DIIS REPORT DIIS DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2006:7 © Copenhagen 2006 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 87-7605-146-3 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk This report is a result of the ongoing research cooperation between The Royal Danish Defence College and the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS). The report is published as part of Defence and Security Studies Research Programme at DIIS, which is funded by the Danish Ministry of Defence. Peter Dahl Thruelsen is Research Fellow at the Institute for Strategy at the Royal Danish Defence College. Tel +45 3915 1211, e-mail: [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2006:7 Summary This report sets out to explore the processes of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) within the context of post-conflict peace-building. I have tried to investigate the transformation of soldiers to civilians in the aftermath of war. The purpose of the research is to facilitate practical recommendations of DDR to be used in future cases of post-conflict peace-building. The empirical focus of this study is the post-conflict DDR programme in Af- ghanistan. -

Troops in Afghanistan: by Louisa Brooke-Holland July 2018 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 08292, 13 July 2018 Troops in Afghanistan: By Louisa Brooke-Holland July 2018 update Approximately 650 UK armed forces personnel are currently deployed in Afghanistan. The Government announced in July 2018 it will deploy an additional 440 troops, bringing the UK total deployment to 1,100 personnel by early 2019. They are part of NATO’s Resolute Support mission to train, advise and assist the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) and institutions. UK personnel are deployed in non-combat roles, principally at the Afghan National Army Officer Academy, protecting coalition and diplomatic personnel and supporting Afghan security forces in the capital. NATO has increased troop numbers since the Resolute Support mission began in January 2015. It currently stands at just over 16,000 troops from 39 nations (the addition of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates will bring this total up to 41). The security situation remains ‘highly unstable’. The UN reported over 10,000 civilian casualties in 2017, over half of which were attributed to the Taliban. Complex and suicide attacks are a leading cause of civilian casualties. The US has significantly increased the number of airstrikes since President Trump unveiled a new South Asia Strategy last August, releasing more weapons in 2017 than in any year since 2012. Library Briefing paper Afghanistan 2017 examines the political situation. This note focuses on UK deployments since 2015. A new role for NATO Between August 2003 and December 2014 NATO led the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. ISAF was wound up on 31 December 2014, although combat operations formally ended for UK forces two months earlier, in October. -

The Politics of Disarmament and Rearmament in Afghanistan

[PEACEW RKS [ THE POLITICS OF DISARMAMENT AND REARMAMENT IN AFGHANISTAN Deedee Derksen ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines why internationally funded programs to disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate militias since 2001 have not made Afghanistan more secure and why its society has instead become more militarized. Supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) as part of its broader program of study on the intersection of political, economic, and conflict dynamics in Afghanistan, the report is based on some 250 interviews with Afghan and Western officials, tribal leaders, villagers, Afghan National Security Force and militia commanders, and insurgent commanders and fighters, conducted primarily between 2011 and 2014. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Deedee Derksen has conducted research into Afghan militias since 2006. A former correspondent for the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant, she has since 2011 pursued a PhD on the politics of disarmament and rearmament of militias at the War Studies Department of King’s College London. She is grateful to Patricia Gossman, Anatol Lieven, Mike Martin, Joanna Nathan, Scott Smith, and several anonymous reviewers for their comments and to everyone who agreed to be interviewed or helped in other ways. Cover photo: Former Taliban fighters line up to handover their rifles to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremony at the pro- vincial governor’s compound. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. j. g. Joe Painter/RELEASED). Defense video and imagery dis- tribution system. The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. -

Cultural Intelligence in Covert Operatives

OVERT ACCEPTANCE: CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE IN COVERT OPERATIVES CHIP MICHAEL BUCKLEY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mercyhurst University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN APPLIED INTELLIGENCE RIDGE SCHOOL FOR INTELLIGENCE STUDIES AND INFORMATION SCIENCE MERCYHURST UNIVERSITY ERIE, PENNSYLVANIA JANUARY 2015 RIDGE SCHOOL FOR INTELLIGENCE STUDIES AND INFORMATION SCIENCE MERCYHURST UNIVERSITY ERIE, PENNSYLVANIA OVERT ACCEPTANCE: CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE IN COVERT OPERATIVES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mercyhurst University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN APPLIED INTELLIGENCE Submitted By: CHIP MICHAEL BUCKLEY Certificate of Approval: ___________________________________ Stephen Zidek, M.A. Assistant Professor The Ridge School of Intelligence Studies and Information Science ___________________________________ James G. Breckenridge, Ph.D. Associate Professor The Ridge School of Intelligence Studies and Information Science ___________________________________ Phillip J. Belfiore, Ph.D. Vice President Office of Academic Affairs January 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Chip Michael Buckley All rights reserved. iii DEDICATION To my father. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge a number of important individuals who have provided an extraordinary amount of support throughout this process. The faculty at Mercyhurst University, particularly Professor Stephen Zidek, provided invaluable guidance when researching and developing this thesis. My friends and classmates also volunteered important ideas and guidance throughout this time. Lastly, my family’s support, patience, and persistent inquiries regarding my progress cannot be overlooked. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Overt Acceptance: Cultural Intelligence in Covert Operatives A Critical Examination By Chip Michael Buckley Master of Science in Applied Intelligence Mercyhurst University, 2014 Professor S. -

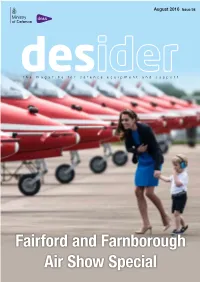

Desider: Issue 98, August 2016

August 2016 Issue 98 desthe magazine for defence equipment and support Fairford and Farnborough Air Show Special B:216 mm T:210 mm S:186 mm THE VALUE OF WORKING TOGETHER TO B:303 mm S:266 mm DELIVER LEADING T:297 mm EDGE CAPABILITY. In a world where our threats need coalitions to defeat them, so too do we need partnerships between nations and companies to develop battle-winning capability. Northrop Grumman has over 2,200 staff across eleven European nations and key roles in delivering critical capabilities such as NATO AGS, F-35, Sentry AWACS, land-based and airborne radars, laser-based aircraft infrared countermeasures, QE Class aircraft carriers, and full-spectrum cyber, as well as developing new technologies to thwart emerging threats. We may not always be visible, but our technology is all pervasive, as is our commitment to build strong European businesses to serve our customers for the long term. ©2015 Northrop Grumman Corporation www.northropgrumman.com/europe 601 West 26th St. Suite 1120 NY, NY 10001 t:646.230.2020 Project Manager: Vanessa Pineda Document Name: NG-INH-Z30663-A_PD1.indd Element: P4CB - standard Current Date: 9-8-2015 12:46 PM Studio Client: Northrop Grumman Bleed: 216 mm w x 303 mm h Prepress: BP Product: INH Trim: 210 mm w x 297 mm h Proof #: 3-RELEASE Proofreader Creative Tracking: NG-INH-Z30663 Safety: 186 mm w x 266 mm h Print Scale: None Page 1 of 1 Print Producer Billing Job: NG-INH-Z29873 Gutter: None InDesign Version: CC Title: UK Brand Ad - Desider Color List: None Art Director Inks: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, -

Specially As Well As Those Undertaken by the MERT

PLEASE TAKE YOUR FREE ISSUE 1, 2020 COPY The Nijmegen March 661 Squadron Op CABRIT Celebrating Our LANDING ZONE Reserve Squadrons CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OPERATIONS ACROSS ALL BOUNDARIES LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2019 1 JOURNAL OF THE JOINT HELICOPTER COMMAND TAKE ON A CHALLENGE HIKE. BIKE. CLIMB. RUN. STANDING SIDE Sign up today for: a guaranteed place in the event support from your Regional Fundraiser BY SIDE WITH THE an RAF Benevolent Fund branded top RAF FAMILY FOR a chance to help the RAF Family. OVER 100 YEARS Find out how we help serving and former members of the RAF and their families. rafbf.org/get-involved FREE CALL FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE EMOTIONAL WELLBEING [email protected] 0800169 2942 WELLBEING BREAKS INDEPENDENT LIVING 020 7307 3321 #makeitcount rafbf.org/help FAMILY AND RELATIONSHIPS TRANSITION The RAF Benevolent Fund is a registered charity in England and Wales (1081009) and Scotland (SC038109). CHALLENGE_ADVERT_JAN20 2 LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2020 LANDING ZONE / CELEBRATING 20 YEARS 2020 3 FOREWORD LZ CELEBRATING 20 YEARS MEET THE TEAM CONTENTS ISSUE 1 2020 EDITORIAL Editor: Sqn Ldr Joan Ochuodho E: [email protected] JHC HISTORY T: 01264 381178 Operations Across All Boundaries 06 – History Of Joint Helicopter Support SALES Squadron ....................................... 26 elcome to this bumper, Sales Manager: Laurence Rowe 20th Anniversary Royal Air Force Tactical Supply Wing 28 E: [email protected] edition of LZ - I’m sure T: 01536 334218 you will enjoy it. Having HONOURS & AWARDS 06 been an SO2 in the 80th Anniversary Awards Evening 18 – original JHC HQ in 1999, DESIGNER commanded a JHC squadron and a Force, HISTORIC REFLECTIONS Designer: Amanda Robinson W Fixed Wing MAS Transfers to the RAF 21 E: [email protected] and been the 1* Capability Director, I hope I’m reasonably well qualified to pen this Look Back: When Two Become One 30 T: 01536 334226 short introduction. -

Democratization in Afghanistan by Chris Rowe

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Democratization in Afghanistan by Chris Rowe What determines whether a specific country embarks on the road to democracy, if it completes that voyage successfully, and finally consolidates democratic values, practices, and institutions? Analysts have debated these issues for decades and have identified a number of historical, structural, and cultural variables that help account for the establishment of successful democracies in some countries and its absence in others. Frequently cited prerequisites for democracy include social and economic modernization; a large and vibrant middle class; and cultural norms and values relating to politics. Yet whatever its determinants, operational democracies normally include contested elections, a free press, and the separation of powers. Although these characteristics have been identified as vital features of a democracy, emerging democracies also need to address serious social and economic injustices that threaten democratic consolidation. Afghanistan is a case in point in this regard. As a burgeoning democracy directly influenced by U.S.-led nation-building efforts, Afghanistan presents a unique and challenging case for democratization. Afghanistan has been ruled by warlords since the era of Taliban rule, and to an extent still is. Informal rule combined with the heroin trade and severe gender inequalities have created a frail foundation on which to promote democratic reforms. Although international human rights, judicial and national assembly commissions have presented significant mandates for change, all have met with problematic results. In order for democracy to take hold in Afghanistan, the fruits of warlord economy–opium production, smuggling, and illicit taxation of trade–must be wrested away from regional power brokers and replaced with socially stable economic incentives. -

Afghanistan Statistics: UK Deaths, Casualties, Mission Costs and Refugees

Research Briefing Number CBP 9298 Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, By Noel Dempsey 16 August 2021 casualties, mission costs and refugees 1 Background Since October 2001, US, UK, and other coalition forces have been conducting military operations in Afghanistan in response to the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. Initially, military action, considered self-defence under the UN Charter, was conducted by a US-led coalition (called Operation Enduring Freedom by the US). NATO invoked its Article V collective defence clause on 12 September 2001. In December 2001, the UN authorised the deployment of a 5,000-strong International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to deploy in, and immediately around, Kabul. This was to provide security and to assist in the reconstruction of the country. While UN mandated, ISAF continued as a coalition effort. US counter terrorism operations under Operation Enduring Freedom remained a distinct parallel effort. In August 2003, NATO took command of ISAF. Over the next decade, and bolstered by a renewed and expanded UN mandate,1 ISAF operations grew 1 UN Security Council Resolution 1510 (2003) commonslibrary.parliament.uk Afghanistan statistics: UK deaths, casualties, mission costs and refugees into the whole country and evolved from security and stabilisation, into combat and counterinsurgency operations, and then to transition. Timeline of major foreign force decisions • October 2001: Operation Enduring Freedom begins. • December 2001: UN authorises the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). • August 2003: NATO assumes ISAF command. • June 2006: ISAF mandate expanded. • 2009: Counterinsurgency operations begin. • 2011-2014: Three-year transition to Afghan-led security operations. • October 2014: End of UK combat operations. -

Research Paper N°12 August 2014

Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement OPERATION CYCLONE AND ITS CONSEQUENCES Research Paper n°12 August 2014 21 boulevard Haussmann, 75009 Paris - France Tél. : 33 1 53 43 92 44 Fax : 33 1 53 43 92 92 www.cf2r.org Association régie par la loi du 1er juillet 1901 SIRET n° 453 441 602 000 19 ! Centre!Français!de!Recherche!sur!le!Renseignement! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! OPERATION!CYCLONE! AND!ITS!CONSEQUENCES! % % % ! ! Dr%FARHAN%ZAHID%% % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Research!Paper!n°12!<!August!2014! _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________% 21%Boulevard%Haussmann,%75009%Paris%<%France% Tél.%:%33%1%53%43%92%44%%%%%Fax%:%33%1%53%43%92%92%%%%%www.cF2r.orG% Association%réGie%par%la%loi%du%1er%juillet%1901%%%%%SIRET%n°%453%441%602%000%19% % 2 ! ! ! ! PRESENTATION%OF% % ! ! ! ! Founded!in!2000,!the!FRENCH!CENTRE!FOR!INTELLIGENCE!RESEARCH!(CF2R)! is! an! independent! Think& Tank,! regulated! by! the! French! Association! Law! of! 1901,! and! specialised! in! the! study! of! intelligence! and! international! security.! Its! missions! are! as! follows:! M! development! of! academic! research! and! publications! on! intelligence! and! international!security,! M!provision!of!expertise!for!public!policy!stakeholders!(decisionMmakers,!government,! lawmakers,!media,!etc.),! M!dispelling!of!myths!surrounding!intelligence!and!explaining!the!role!of!intelligence! to!the!general!public.! ! ! !%ORGANISATION% ! ! The! FRENCH! CENTER! FOR! INTELLIGENCE! RESEARCH! (CF2R)! -

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: Army/Sec/16/03/FOI/2017/11467 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk Mr Mike Cox 12 December 2017 [email protected] Dear Mr Cox, Thank you for your email of 13 November in which you requested the following information: Can you please supply the following information regarding recent Roulement Tours : 1. FIRIC (Falkland Islands Roulement Infantry Company) Which companies of which battalions fulfilled their FIRIC commitment: 4.2014 - 10.2014 (between 1 Mercian and 5 Rifles tours) 6.2015 -10.2015 (between 2 Rifles and 1 Welsh Guards tours) 2.2016 - 5.2016 (between 1 Grenadier Guards and 1 Yorkshire tours) 8.2016 - To date (following 4 Para tour) 2. Operation Elgin (Bosnia) Which units have been assigned to this commitment since 1 Scots in 2014. 3. Operation Toral (Afghanistan) If 1 R Anglian tour was Toral 1, what operational name was given to previous commitments by 1 Coldstream Guards and 2 Rifles during the period March 2014 and January 2015. I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm the information in scope of your request is held and is detailed below. 1. Falkland Islands Roulement Infantry Company The following infantry companies conducted the requested FIRIC Tours: Ser Date Battalion Company (a) (b)